Introduction to Chapter 3

3

Colonial America amid Global Change

1680–1750

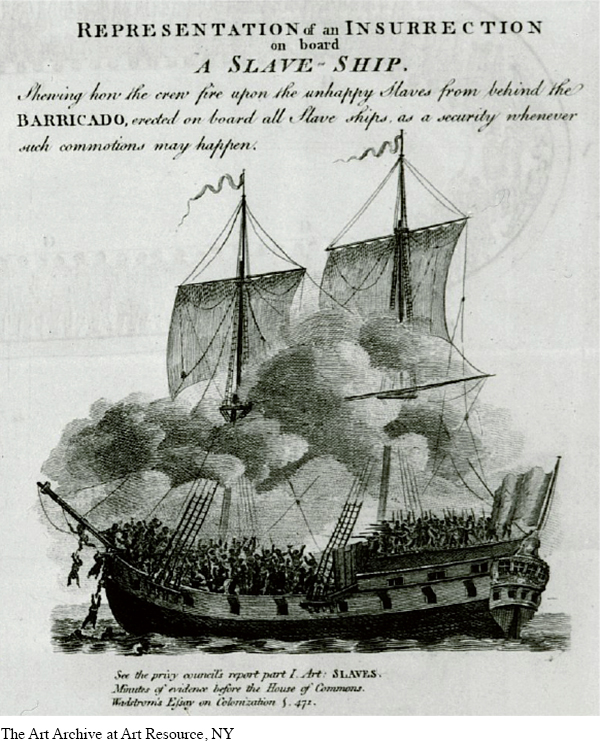

WINDOW TO THE PAST

Plan of a Slave Ship, 1794

By the mid-eighteenth century, slave traders were designing ships specifically for the purpose of transporting captured Africans to the Americas for sale. This image of the English slave ship Brooks, based on a ship maker’s diagram, was initially created as a broadside in 1789 by English opponents of the slave trade to highlight the trade’s brutality. A few years later, a shipboard insurrection by enslaved Africans was added to the original diagram, suggesting one likely response to such brutality. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 3.2.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Compare the development of Spanish, French, and English colonies from the late seventeenth to the mid-eighteenth century.

Analyze the effects of European wars on relations among different groups of European colonists and between colonists and diverse Indian nations in North America.

Examine how the American colonies became part of a global trading network.

Describe the changing character of labor in the English colonies and the rise of slavery.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

In 1729, at age thirty, William Moraley Jr. signed an indenture to serve a five-year term as a “bound servant” in the “American Plantations.” This was not what his parents had imagined for him. The son of a journeyman watchmaker, Moraley received a good education and was offered a clerkship with a London lawyer. But Moraley preferred London’s pleasures to legal training. At age nineteen, out of money, he was forced to return home and become an apprentice watchmaker for his father. Moraley made a poor apprentice, and in 1725, fed up with his son’s lack of enterprise, Moraley’s father rewrote his will, leaving him just 20 shillings. When Moraley’s father died unexpectedly, his wife gave her son 20 pounds, and in 1728 Moraley headed back to London.

But times were hard in London, and Moraley failed to find work. After being imprisoned for debt, he sold his labor for five years in return for passage to America. Arriving in the colonies in December 1729, Moraley was indentured to Isaac Pearson, a Quaker clockmaker and goldsmith in Burlington, New Jersey. Preferring to live in a large city like Philadelphia, Moraley ran away but was soon captured. Most runaway servants had their contracts extended, but Moraley did not. For the next three years, he worked for Pearson alongside another indentured servant and an enslaved boy. Pearson allowed Moraley to travel the countryside fixing clocks and watches, and the servant observed the far worse conditions of enslaved workers. Perhaps having recouped his investment, Pearson released Moraley from his contract two years early.

Moraley spent the next twenty months traveling the northern colonies, but found no steady employment. Hounded by creditors, he returned to England, penniless and unemployed. In 1743, hoping to cash in on popular interest in adventure tales, he published an account of his travels. In the book, entitled The Infortunate, the Voyage and Adventures of William Moraley, an Indentured Servant, he offered a poor man’s view of eighteenth-century North America. Like so much else in Moraley’s life, the book was not a success.

In 1738, while Moraley was back in England trying to carve out a career as a writer, sixteen-year-old Eliza Lucas, the eldest daughter of Colonel George Lucas, arrived at Wappoo, her father’s estate near Charleston, South Carolina. Eliza had been born on Antigua, where her father served with the British army and owned a sugar plantation. The move north, made necessary by her mother’s ill health, created an unusual opportunity for Eliza, who was left in charge of the estate when Colonel Lucas was called back to Antigua in May 1739.

For the next five years, Eliza Lucas managed Wappoo and two other Carolina plantations owned by her father. Rising each day at 5 a.m., she checked on the fields and the enslaved laborers who worked them, balanced the books, nursed her mother, taught her younger sister to read, and wrote to her younger brothers at school in England. She also befriended neighboring planters, including Charles Pinckney, whom she would later marry, adding her landholdings to his.

While still single, Eliza improved the value of her family’s estates by experimenting with new crops. With her father’s enthusiastic support, she cultivated indigo, a plant used for making textile dyes. When her experiments proved successful, Eliza Lucas encouraged other planters to follow her lead, and with financial aid from the colonial legislature and Parliament, indigo became a profitable export from South Carolina, second only to rice.

The American histories of William Moraley and Eliza Lucas were shaped by a profound shift in global trading patterns that resulted in the circulation of labor and goods among Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas. Between 1680 and 1750, indentured servants, enslaved Africans, planters, soldiers, merchants, and artisans traveled along these new trade networks. So, too, did sugar, rum, tobacco, indigo, cloth, and a host of other items. As England, France, and Spain expanded their empires, colonists developed new crops for export and increased the demand for manufactured goods from home. Yet the vibrant, increasingly global economy was fraught with peril. Economic crises, the uncertainties of maritime navigation, and outbreaks of war caused constant disruptions. For some, the opportunities offered by colonization outweighed the dangers; for others, fortune was less kind, and the results were disappointing, even disastrous.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 69

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 51

Chapter Timeline