The Pueblo Revolt and Spain’s Fragile Empire

As New France pushed westward and southward, Spain continued to oversee an empire that was spread dangerously thin on its northern reaches. In New Mexico, tensions between Spanish missionaries and encomenderos and the Pueblo nation had simmered for decades (see “Spain’s Global Empire Declines” in chapter 2). Relations worsened in the 1670s when a drought led to famine among many area Indians and brought a revival of Indian rituals that the Spaniards considered threatening. In addition, Spanish forces failed to protect the Pueblos against devastating raids by Apache and Navajo warriors. Finally, Catholic prayers proved unable to stop Pueblo deaths in a 1671 epidemic. When some of the Pueblos returned to their traditional priests, Spanish officials hanged three Indian leaders for idolatry and whipped and incarcerated forty-three others. Among those punished was Popé, a militant Pueblo who upon his release began planning a broad-based revolt.

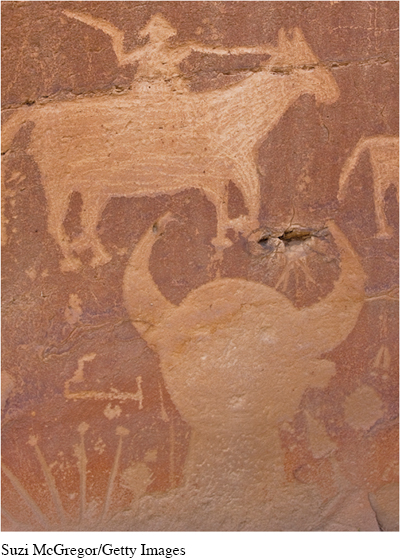

On August 10, 1680, seventeen thousand Pueblo Indians initiated a coordinated assault on numerous Spanish missions and forts. They destroyed buildings and farms, burned crops and houses, and smeared excrement on Christian altars. The Spaniards retreated to Mexico without launching any significant counterattack.

Yet the Spaniards returned in the 1690s and reconquered parts of New Mexico, aided by growing internal conflict among the Pueblos and raids by the Apache. The governor general of New Spain worked hard to subdue the province and in 1696 crushed the rebels and opened new lands for settlement. Meanwhile Franciscan missionaries improved relations with the Pueblos by allowing them to retain more indigenous practices.

Yet despite the Spanish reconquest, in the long run the Pueblo revolt limited Spanish expansion by strengthening other indigenous peoples in the region. In the aftermath of the revolt, some Pueblo refugees moved north and taught the Navajo how to grow corn, raise sheep, and ride horses. Through the Navajo, the Ute, Shoshone, and Comanche peoples also gained access to horses. By the 1730s, the Comanches launched mounted bison hunts as well as raids on other Indian nations. At Taos, they traded Indian captives into slavery for more horses and guns. Thus the Pueblos provided other Indian nations with the means to support larger populations, wider commercial networks, and more warriors, allowing them to continue to contest Spanish rule.

At the same time, Spain sought to reinforce its claims to Texas (named after the Tejas Indians) in response to French settlements in the lower Mississippi valley. In the early eighteenth century, Spanish missions and forts appeared along the route from San Juan Batista to the border of present-day Louisiana. Although small and scattered, these outposts were meant to ensure Spain’s claim to Texas. But the presence of large and powerful Indian nations, including the Caddo and the Apache, forced Spanish residents to accept many native customs in order to maintain their presence in the region.

Spain also faced challenges to its authority in Florida, where Indians resisted the spread of cattle ranching in the 1670s. Meanwhile the English wooed Florida natives by exchanging European goods for deerskins. Some Indians then moved their settlements north to the Carolina border. The growing tensions along this Anglo-Spanish border would turn violent when Europe itself erupted into war.

REVIEW & RELATE

What role did the crown play in the expansion of the English North American colonies in the second half of the seventeenth century?

How did the development of the Spanish and French colonies in the late seventeenth century differ from that of the English colonies?

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 75

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 56

Chapter Timeline