Introduction to Chapter 4

4

Religious Strife and Social Upheavals

1680–1750

WINDOW TO THE PAST

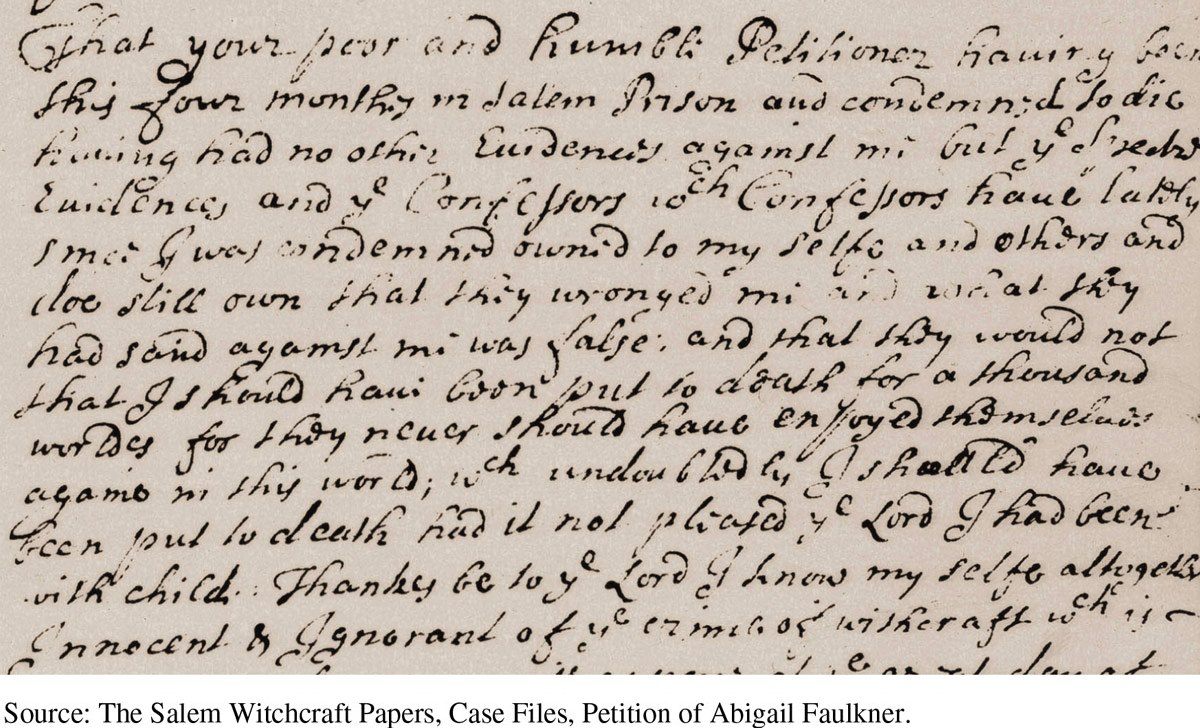

Abigail Faulkner Appeals Her Conviction for Witchcraft, 1692

Abigail Faulkner, the daughter of a minister and wife of a large landowner, was convicted of witchcraft in Salem, Massachusetts, but maintained her innocence. Any woman sentenced to death had her execution postponed if she was pregnant. Faulkner used the delay in carrying out her death penalty to petition the Massachusetts governor for her release based on what she considered insufficient evidence. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 4.1.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Explain the relationships among religious, economic, and political tensions and accusations of witchcraft.

Describe family dynamics, particularly between husbands and wives, and how they changed over time and differed by class and region.

Understand the ways that economic developments and increasing diversity fueled conflicts in early eighteenth-century colonial society.

Explain the emergence of the Great Awakening and identify its critics and legacies.

Describe how the Great Awakening shaped political developments in the 1730s and 1740s.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

The son of a Scots-Irish clergyman, Gilbert Tennent was born in Vinecash, Ireland, in 1703 and at age fifteen moved with his family to Philadelphia. After receiving an M.A. from Yale College in 1725, Gilbert was ordained a Presbyterian minister in New Brunswick, New Jersey, with little indication of the role he would play in a major denominational schism.

Tennent entered the ministry at a critical moment, when leaders of a number of denominations had become convinced that the colonies were descending into spiritual apathy. Tennent dedicated himself to sparking a rebirth of Christian commitment, and by the mid-1730s the pastor had gained fame as a revival preacher. At the end of the decade, he journeyed through the middle colonies with Englishman George Whitefield, an Anglican preacher known for igniting powerful revivals. Then in the fall of 1740, following the death of his wife, Tennent launched his own evangelical “awakenings.”

Revivals inspired thousands of religious conversions across denominations, but they also fueled conflicts within established churches. Presbyterians in Britain and America disagreed about whether only those who had had a powerful, personal conversion experience were qualified to be ministers. Tennent made his opinion clear by denouncing unconverted ministers in his sermons, a position that led to his expulsion from the Presbyterian Church in 1741. But many local churches sought converted preachers, and four years later a group of ejected pastors formed a rival synod that trained its own evangelical ministers.

While ministers debated the proper means of saving sinners, ordinary women and men searched their souls. In Pomfret, Connecticut, Sarah Grosvenor certainly feared for hers in the summer of 1742 when the unmarried nineteen-year-old realized she was pregnant. Her situation was complicated by her status in the community. She was the daughter of Leicester Grosvenor, an important landowner, town official, and member of the Congregational Church.

The pew next to Sarah and her family was occupied by Nathaniel Sessions and his sons, including the twenty-six-year-old Amasa, who had impregnated Sarah. Many other young women became pregnant out of wedlock in the 1740s, but families accepted the fact as long as the couple married before the child was born. In Sarah’s case, however, Amasa refused to marry her and suggested instead that she have an abortion.

Although Sarah was reluctant to follow this path, Amasa insisted. When herbs traditionally used to induce a miscarriage failed, Amasa introduced Sarah to John Hallowell, a doctor who claimed he could remove the fetus with forceps. After admitting her agonizing situation to her older sister Zerviah and her cousin Hannah, Sarah allowed Hallowell to proceed. He finally induced a miscarriage, but Sarah soon grew feverish, suffered convulsions, and died ten days later.

Apparently Sarah’s and Amasa’s parents were unaware of the events leading to her demise. Then in 1745, a powerful religious revival swept through the region, and Zerviah and Hannah suffered great spiritual anguish. It is likely they finally confessed their part in the affair since that year officials brought charges against Amasa Sessions and John Hallowell for Sarah’s death. At the men’s trial, Zerviah and Hannah testified about their roles and those of Sessions and Hallowell. Still, their spiritual anguish did not lead to earthly justice. Hallowell was found guilty but escaped punishment by fleeing to Rhode Island. Sessions was acquitted and remained in Pomfret, where he married and became a prosperous farmer.

The American histories of Gilbert Tennent and Sarah Grosvenor were shaped by powerful religious forces—later called the Great Awakening—that swept through the colonies in the early eighteenth century. Those forces are best understood in the context of larger social, economic, and political changes. Many young people became more independent of their parents and developed tighter bonds with siblings, cousins, and neighbors their own age. Towns and cities developed clearer hierarchies by class and status, which could protect wealthier individuals from being punished for their misdeeds. A double standard of sexual behavior became more entrenched as well, with women subject to greater scrutiny than men for their sexual behavior. Of course, most young women did not meet the fate of Sarah Grosvenor. Still, pastors like Gilbert Tennent feared precisely such consequences if the colonies—growing ever larger and more diverse—did not reclaim their religious foundations.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 103

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 79

Chapter Timeline