Battles and Boundaries on the Frontier

The sweeping character of the British victory encouraged thousands of colonists to move farther west, into lands once controlled by France. This exacerbated tensions that were already rising on the southern and western frontiers of British North America.

In late 1759, for example, the Cherokee nation, reacting to repeated incursions on its hunting grounds, dissolved its long-term trade agreement with South Carolina. Cherokee warriors attacked backcountry farms and homes, leading to counterattacks by British troops. The fighting continued into 1761, when Cherokees on the Virginia frontier launched raids on colonists there. General Jeffrey Amherst then sent 2,800 troops to invade Cherokee territory and end the conflict. The soldiers sacked fifteen villages; killed men, women, and children; and burned acres of fields.

Although British raids diminished the Cherokees’ ability to mount a substantial attack, sporadic assaults on frontier settlements continued for years. These conflicts fueled resentments among backcountry settlers not only against Indians but also against political leaders in eastern parts of the colonies who rarely provided sufficient resources for frontier defense.

A more serious conflict erupted in the Ohio River valley when Indians realized the consequences of British victories. When the British captured French forts along the Great Lakes and in the Ohio valley in 1760, they immediately antagonized local Indian groups by hunting and fishing on tribal lands and depriving villages of much-needed food. British traders also defrauded Indians on numerous occasions and ignored traditional obligations of gift giving.

The harsh realities of the British regime led some Indians to seek a return to ways of life that preceded the arrival of white men. An Indian visionary named Neolin preached that Indians had been corrupted by contact with Europeans and urged them to purify themselves by returning to their ancient traditions, abandoning white ways, and reclaiming their lands. Neolin was a prophet, not a warrior, but his message inspired others, including an Ottawa leader named Pontiac.

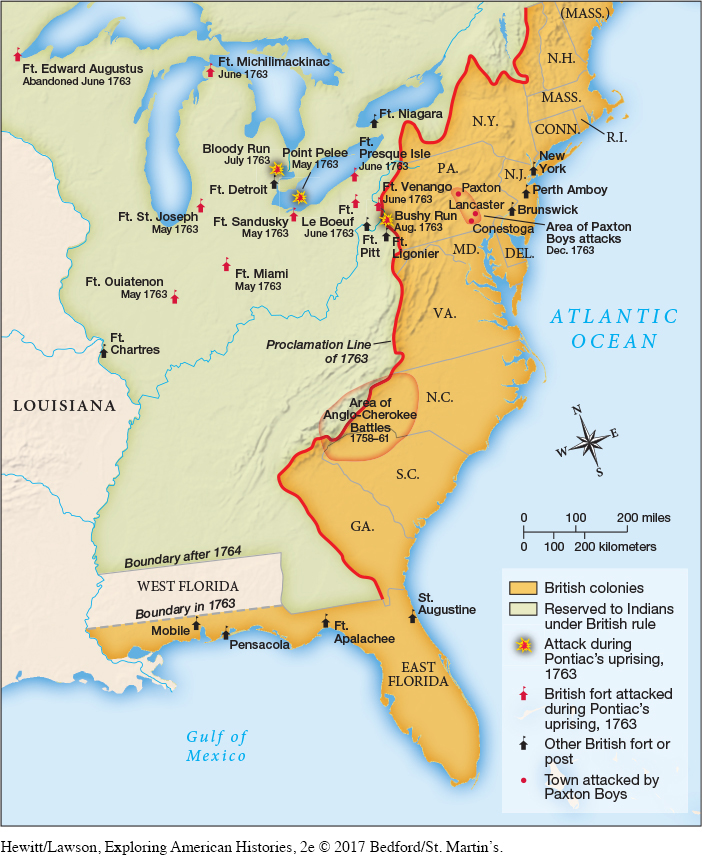

When news arrived in early 1763 that France was about to cede all of its North American lands to Britain and Spain, Pontiac convened a council of more than four hundred Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Huron leaders near Fort Detroit. Drawing on Neolin’s vision, he proclaimed, “It is important my brothers, that we should exterminate from our land this nation [Britain], whose only object is our death. You must all be sensible,” he continued, “that we can no longer supply our wants the way we were accustomed to do with our Fathers the French.” Pontiac then mobilized support to drive out the British. In May 1763, Pontiac’s forces laid siege to Detroit and soon gained the support of eighteen Indian nations. They then attacked Fort Pitt and other British frontier outposts as well as white settlements along the Virginia and Pennsylvania frontier (Map 5.2).

Accounts of violent encounters with Indians on the frontier circulated throughout the colonies and sparked resentment among settlers as well as British troops. Many colonists did not distinguish between friendly and hostile Indians. In December 1763, a group of men from Paxton Creek, Pennsylvania, raided families of peaceful, Christian Conestoga Indians near Lancaster, killing thirty. Protests from eastern colonists infuriated the Paxton Boys, who then marched on Philadelphia demanding protection from “savages” on the frontier.

Although violence on the frontier slowly subsided, neither side had achieved victory. Without French support, Pontiac and his followers had to retreat. Meanwhile, Benjamin Franklin negotiated a truce between the Paxton Boys and the Pennsylvania authorities, but it did not settle the fundamental issues over protection of western settlers. Convinced that it could not endure further costly frontier clashes, the British crown issued a proclamation in October 1763 forbidding colonial settlement west of a line running down the Appalachian Mountains to create a buffer between Indians and colonists. But Parliament also ordered Colonel Bouquet to subdue hostile Indians in the Ohio region.

The Proclamation Line of 1763 denied colonists the right to settle west of the Appalachian Mountains. Instituted just months after the Peace of Paris was signed, the Proclamation Line frustrated colonists who sought the economic benefits won by a long and bloody war. Small farmers, backcountry settlers, and squatters who had hoped to improve their lot by acquiring rich farmlands were told to stay put. Meanwhile Washington and other wealthy speculators managed to acquire additional western lands, certain that the Proclamation was merely “a temporary expedient to quiet the Minds of the Indians.”

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 144

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 110

Chapter Timeline