Introduction to Chapter 7

7

Forging a New Nation

1783–1800

WINDOW TO THE PAST

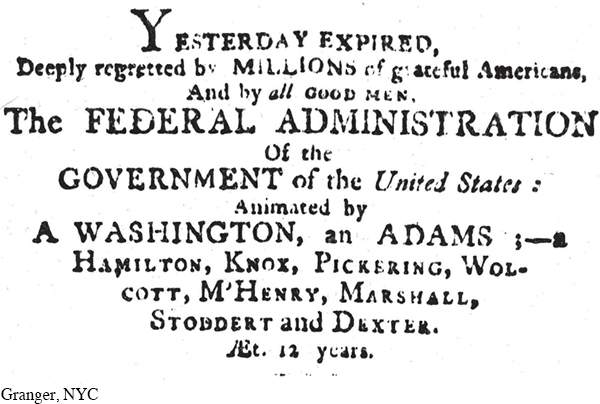

The Burial of the Federal Administration

Following the Revolution, Americans had to develop political structures, economic policies, and diplomatic relations with Indians and Europeans. For the first twelve years, George Washington and the Federalists led this effort. In 1798 an opposition party emerged. When its leader, Thomas Jefferson, was inaugurated president of the United States on March 4, 1801, the Columbia Centinel published a broadside lamenting the death of Federalist leadership. To discover more about what this primary source can show us, see Document 7.4.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Identify the major threats to the new nation after the Revolution.

Explain how different groups of Americans were marginalized in this period and how they responded.

Describe the chief debates over the Constitution and its ratification.

Evaluate the ways that the young nation’s economic policies affected its relations with European nations abroad and on the U.S. frontier and fostered competing political views.

Describe how the presidency of John Adams exacerbated differences between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans and led to Thomas Jefferson’s election in 1800.

AMERICAN HISTORIES

One of six children born to Irish parents in Hopkinton, Massachusetts, Daniel Shays received little formal education. In 1772, age twenty-five, he married, had a child, and settled into farming. But in April 1775, he, his father, and his brother raced toward Concord to meet the British forces. By June, he was among the patriots defending Bunker Hill.

After distinguished service in the Continental Army, Shays purchased a farm in Pelham, Massachusetts, in 1780 and hoped to return to a normal life. Instead, economic turmoil roiled the region and the nation. Many farmers had fallen into debt while fighting for independence. They returned to an economic recession and increased taxes as state governments labored to repay wealthy creditors and fund their portion of the federal budget. In western Massachusetts, many farmers faced eviction. Shays kept his farm and represented his town at county conventions that petitioned the state government for economic relief. However, the legislature largely ignored the farmers’ concerns.

In 1786, angered by the state’s failure to act, armed groups of farmers attacked courthouses throughout western Massachusetts. Although a reluctant leader, Shays headed the largest band of more than a thousand farmer-soldiers. In January 1787, this group headed to the federal arsenal at Springfield, Massachusetts, to seize guns and ammunition. The farmers were routed by state militia and pursued by governor James Bowdoin’s army. Many rebel leaders were captured; others, including Shays, escaped to Vermont and New York. Four were convicted and two were hanged before Bowdoin granted amnesty to the others in hopes of avoiding further conflict.

This uprising, known as Shays’s Rebellion, alarmed many state and national leaders who feared such insurgencies might emerge elsewhere. Among those outraged by the rebels was Alexander Hamilton, a young New York politician. Hamilton was born illegitimate and impoverished in the British West Indies. Orphaned at eleven, he was apprenticed to a firm of merchants that sent him to the American colonies. There Hamilton was drawn into the activities of radical patriots and joined the Continental Army in 1776.

During the war, Hamilton fell in love with Elizabeth Schuyler, who came from a wealthy New York family. They married in December 1780. After the war, Hamilton used military and marital contacts to establish himself as a lawyer and financier in New York City. In 1786, Hamilton was elected to the New York State legislature, where he focused on improving the state’s finances, and served as a delegate to a convention on interstate commerce held in Annapolis, Maryland. Hamilton and several other delegates advocated a stronger central government. They pushed through a resolution calling for a second convention “to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union.”

Although the initial response to the call was lukewarm, the eruption of Shays’s Rebellion and the government’s financial problems soon convinced many political leaders that change was necessary. Although Hamilton played only a small role in the 1787 convention in Philadelphia, he worked tirelessly for ratification of the Constitution drafted there. When the new federal government was established in 1789, Hamilton became the nation’s first secretary of the treasury.

The American histories of Daniel Shays and Alexander Hamilton demonstrate that the patriots may have come together to win the Revolutionary War but that they did not share a common vision of the new nation. Despite the suppression of Shays’s Rebellion, the grievances that fueled the uprising persisted and Americans differed significantly over how best to resolve them. By 1787, demand for a stronger central government led to the ratification of a new U.S. Constitution. Hamilton played a leading role in advocating and establishing the new government, particularly by seeking to stabilize and strengthen the national economy. While many political and economic elites applauded his efforts, other national leaders and many ordinary citizens opposed them. These differences, exacerbated by foreign and frontier crises, eventually led to the development of competing political parties and the first contested presidential election in American history.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 205

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 153

Chapter Timeline