Indians, Land, and the Northwest Ordinance

One anonymous petitioner at Newburgh suggested that the officers move as a group to “some unsettled country” and let the confederation fend for itself. In reality, no such unsettled country existed beyond the thirteen states. Numerous Indian nations and growing numbers of American settlers claimed control of western lands. In 1784 some two hundred Indian leaders from the Iroquois, Shawnee, Creek, Cherokee, and other nations gathered in St. Louis, where they complained to the Spanish governor that the Americans were “extending themselves like a plague of locusts.”

Despite the continued presence of British and Spanish troops in the Ohio River valley, the United States hoped to convince Indian nations that it controlled the territory. In October 1784, U.S. commissioners met with Iroquois delegates at Fort Stanwix, New York, and demanded land cessions in western New York and the Ohio valley. When the Seneca chief Cornplanter and other leaders refused, the commissioners insisted that “you are a subdued people” and must submit. An exchange of gifts and captives taken during the Revolution finally ensured the deal. Indian leaders not at the meeting disavowed the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. But the confederation government insisted it was legal, and New York State began surveying and selling the land. With a similar mix of negotiation and coercion, U.S. commissioners signed treaties at Fort McIntosh, Pennsylvania (1785), and Fort Finney, Ohio (1786), claiming lands held by the Wyandots, Delawares, Shawnees, and others.

Explore

See Document 7.1 for a pan-Indian perspective on relations with the U.S. government.

As eastern Indians were increasingly pushed into the Ohio River valley, they crowded onto lands already claimed by other nations. Initially, these migrations increased conflict among Indians, but eventually some leaders used this forced intimacy to launch pan-Indian movements against further American encroachment on their land.

Indians and U.S. political leaders did share one concern: the vast numbers of squatters, mainly white men and women, living on land to which they had no legal claim. In fall 1784 George Washington traveled west to survey nearly thirty thousand acres of territory he had been granted as a reward for military service. He found much of it occupied by squatters who refused to acknowledge his ownership. Such flaunting of property rights deepened his concerns about the weaknesses of the confederation government.

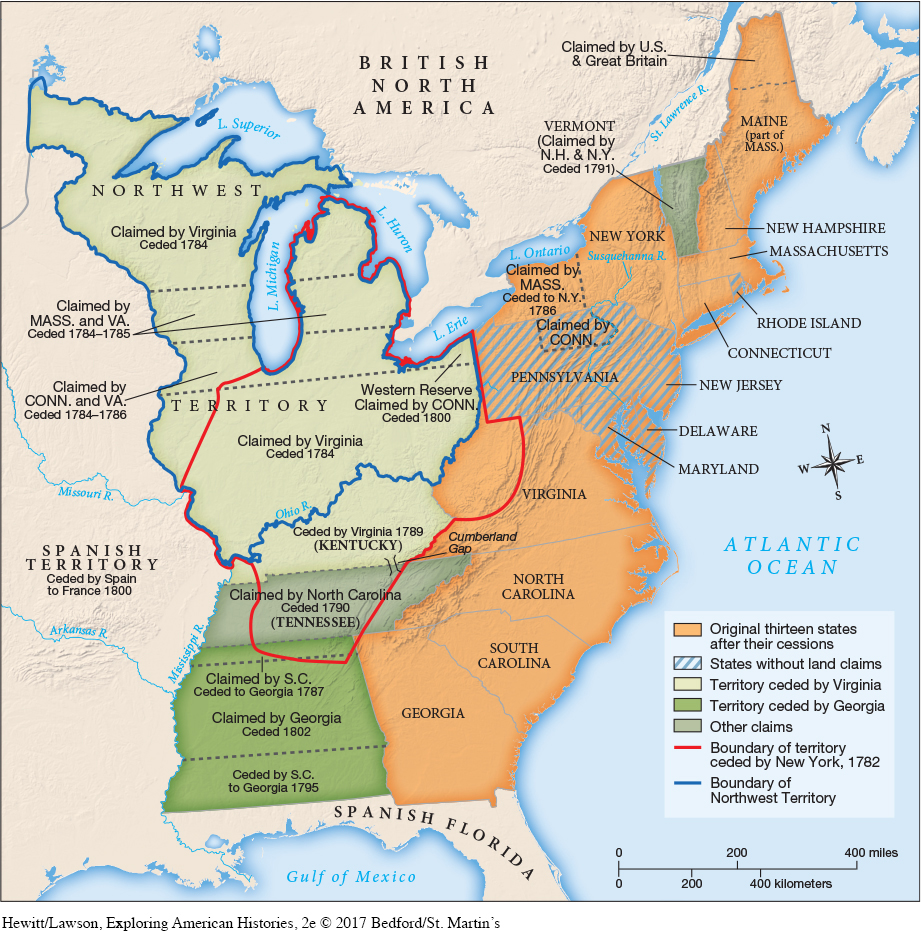

The confederation congress was less concerned about individual property rights and more with the refusal of some states to cede the western lands they claimed to federal control. Slowly, between 1783 and 1785, the congress finally persuaded the two remaining states with the largest claims, Virginia and Massachusetts, to relinquish all territory north of the Ohio River (Map 7.1).

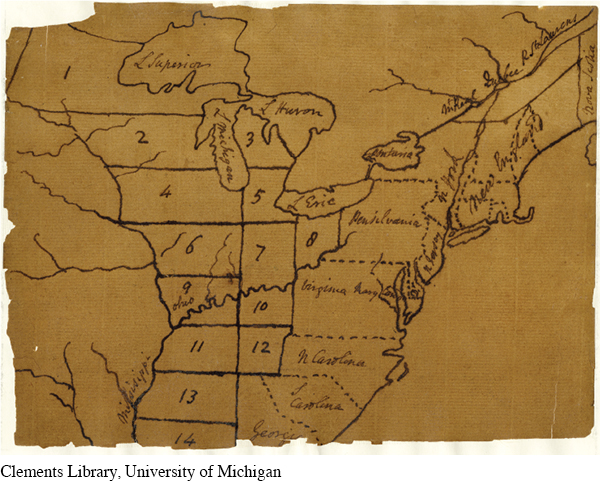

To regulate this vast territory, Thomas Jefferson drafted the Northwest Ordinance in 1785. It provided that the territory be surveyed and divided into adjoining townships. He hoped to carve nine small states out of the region to enhance the representation of western farmers and to ensure the continued dominance of agrarian views in the national government. The congress revised his proposal, however, stipulating that only three to five states be created from the vast territory and thereby limiting the future clout of western settlers in the federal government.

The population of the territory grew rapidly, with speculators buying up huge tracts of land and selling smaller parcels to eager settlers. In response, congressional leaders modified the Northwest Ordinance in 1787, clarifying the process by which territories could become states. The congress appointed territorial officials and guaranteed residents the basic rights of U.S. citizens. After a territory’s population reached 5,000, residents could choose an assembly, but the territorial governor retained the power to veto legislation. When a prospective state reached a population of 60,000, it could apply for admission to the United States. Thus the congress established an orderly system by which territories became states in the Union.

The 1787 ordinance also tried to address concerns about race relations in the region. It encouraged fair treatment of Indian nations but did not include any means of enforcing such treatment and failed to resolve Indian land claims. It also abolished slavery throughout the Northwest Territory but mandated the return of fugitive slaves to their owners to forestall a flood of fugitives.

The 1787 legislation did not address territory south of the Ohio River. As American settlers streamed into areas that became Kentucky and Tennessee, they confronted Creek, Choctaw, and Chickasaw tribes, well supplied with weapons by Spanish traders, as well as Cherokee who had sided with the British during the Revolution. Conflicts there were largely ignored by the national government for the next quarter century.

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 209

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 156

Chapter Timeline