War Erupts with Britain

Convinced that British officials in Canada fueled Indian resistance, many Democratic-Republicans demanded an end to British intervention on the western frontier. Insisting that the United States also stop British interference in transatlantic trade, some called for the United States to declare war. Yet merchants in the Northeast, who still hoped to renew trade with Great Britain and the British West Indies, feared the commercial disruptions that war entailed. Thus New England Federalists adamantly opposed a declaration of war.

For months, Madison avoided taking a clear stand on the issue. On June 1, 1812, however, with diplomatic efforts exhausted, Madison sent a secret message to Congress outlining U.S. grievances against Great Britain. Within weeks, Congress declared war by sharply divided votes in the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Supporters claimed that a victory over Great Britain would end threats to U.S. sovereignty and raise Americans’ stature in Europe, but the nation was ill prepared to launch a major offensive against such an imposing foe. Cuts in federal spending and falling tax revenues over the previous decade had diminished military resources. The U.S. navy, for example, established under President Adams, had been reduced to only six small gunboats by President Jefferson. Democratic-Republicans had also failed to recharter the Bank of the United States when it expired in 1811, so the nation lacked a vital source of credit. Nonetheless, many in Congress believed that Britain would be too engaged by the ongoing conflict with France to attack the United States.

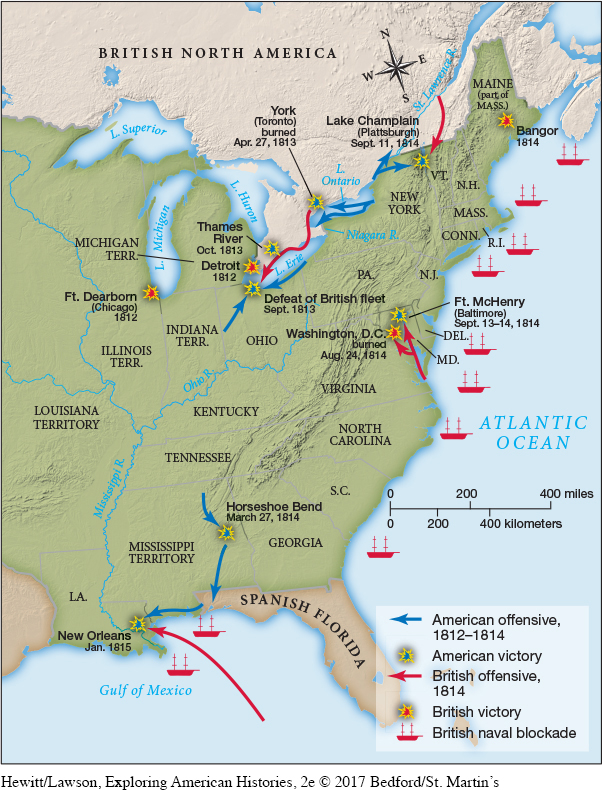

Meanwhile U.S. commanders devised plans to attack Canada, but the U.S. army and navy proved no match for Great Britain and its Indian allies. Instead, Tecumseh, who was appointed a brigadier general in the British army, helped capture Detroit. Joint British and Indian forces also launched successful attacks on Fort Dearborn, Fort Mackinac, and other points along the U.S.-Canadian border.

Even as U.S. forces faced numerous defeats in the summer and fall of 1812, American voters reelected James Madison as president. His narrow victory demonstrated the geographical divisions caused by the war. Madison won most western and southern states, where the war was most popular, and lost in New England and New York, where Federalist opponents held sway.

After a year of fighting, U.S. forces finally drove the British back into Canada (Map 9.1). A naval victory on Lake Erie led by Commodore Oliver Perry proved crucial to U.S. success. Soon after, Tecumseh was killed in battle and U.S. forces burned York (present-day Toronto). Yet just as U.S. prospects in the war improved, New England Federalists demanded retreat. The war devastated the New England maritime trade, causing economic distress throughout the region. In the fall of 1813, state legislatures in New England withdrew their support for any invasion of “foreign British soil,” and Federalists in Congress sought to block war appropriations and the deployment of local militia units into the U.S. army.

New England Federalists were not powerful enough to change national policy, but they called a meeting at Hartford, Connecticut, in 1814 to “deliberate upon the alarming state of public affairs.” Some participants at the Hartford Convention called for New England’s secession from the United States. Most, however, supported amendments to the U.S. Constitution that would constrain federal power by limiting presidents to a single term and ensuring they were elected from diverse states (ending Virginia’s domination of the office). Other amendments would require a two-thirds majority in Congress to declare war or prohibit trade.

The Hartford resolutions gained increased attention as British forces launched new attacks into the United States and British warships blockaded U.S. ports. In August 1814, the British sailed up the Chesapeake. As American troops retreated, Dolley Madison and a family slave, Peter Jennings, gathered up government papers and valuable belongings before fleeing the White House. The redcoats then burned and sacked Washington City. Nonetheless, U.S. troops quickly rallied to defeat the British in Maryland and expel them from Washington and New York.

Meanwhile news arrived in March 1814 that militiamen from Tennessee led by Andrew Jackson had defeated a force of Creek Indians, important British allies. Cherokee warriors (including John Ross), longtime foes of the Creek, joined the fight. At the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, in present-day Alabama, the combined U.S.-Cherokee forces slaughtered eight hundred Creek warriors. Although some Americans were appalled at the slaughter, in the resulting treaty the Creek nation lost two-thirds of its tribal domain.

Despite sporadic victories, the United States was no closer to winning the war when the British ended the war in Europe in June 1814 by defeating Napoleon. Six months later, the British fleet landed thousands of seasoned troops at New Orleans. Still, the British were losing steam as well, and representatives of the two countries met in Ghent, Belgium, to negotiate a peace settlement. On Christmas Eve 1814, the Treaty of Ghent was signed, returning to each nation the lands it controlled before the war.

News of the treaty had not yet reached the United States in January 1815, when U.S. troops under General Andrew Jackson attacked and routed the British army at New Orleans. The victory cheered Americans, who, unaware that peace had already been achieved, made Jackson a national hero.

Although the War of 1812 achieved no formal territorial gains, it did represent an important defense of U.S. sovereignty and garnered international prestige for the young nation. In addition, Indians on the western frontier lost a powerful ally when British representatives at Ghent failed to act as advocates for their allies. Thus, in practical terms, the U.S. government gained greater control over vast expanses of land in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys.

REVIEW & RELATE

How were conflicts with Indians in the West connected to ongoing tensions between the United States and Great Britain on land and at sea?

What were the long-term consequences of the War of 1812?

Exploring American HistoriesPrinted Page 279

Exploring American Histories Value EditionPrinted Page 208

Chapter Timeline