Concept 39.1: Animals Use Innate and Adaptive Mechanisms to Defend Themselves against Pathogens

Animals have a number of ways of defending themselves against pathogens—harmful organisms and viruses that can cause disease. These defense systems are based on the distinction between self—the animal’s own molecules—and nonself, or foreign, molecules. Some defensive mechanisms are present all the time. For example, the skin is always present to protect a mammal from invaders. Other defenses are activated in response to invaders. These responses involve three phases:

- Recognition phase: The organism must be able to recognize pathogens and discriminate between self and nonself.

- Activation phase: The recognition event leads to a mobilization of cells and molecules to fight the invader.

- Effector phase: The mobilized cells and molecules destroy the invader.

There are two general types of defense mechanisms:

- Innate defenses, or nonspecific defenses, are inherited mechanisms that provide the first line of defense against pathogens. They include physical barriers such as the skin, molecules that are toxic to invaders, and phagocytic cells that ingest invaders. This system recognizes broad classes of organisms or molecules and gives a quick response, within minutes or hours. Some innate defenses are present all the time, whereas others are rapidly activated in response to an injury or invasion by a pathogen. All animals (and plants—see Chapter 28) have innate defenses.

LINK

Phagocytosis is a form of endocytosis in which a cell engulfs a large particle or another cell; see Concept 5.4

- Adaptive defenses are aimed at specific pathogens and are activated by the innate immune system. For example, cells in the adaptive defense system can make antibodies—proteins that will recognize, bind to, and aid in the destruction of specific pathogens, if the pathogens enter the body. Adaptive defenses are typically slow to develop and long-lasting. Adaptive defenses evolved in vertebrate animals.

Immunity occurs when an organism has sufficient defenses to successfully avoid biological invasion by a pathogen.

Innate defenses evolved before adaptive defenses

All animals have innate defenses against their enemies. For example, the crustacean Tachypleus tridentatus—the Japanese horseshoe crab—first appeared in the fossil record about 400 million years ago. It relies only on innate defenses. These defenses include barriers, defensive cells, and defensive molecules.

- Barriers include physical, chemical, and biological mechanisms for resisting infections (see Concept 39.2). The horseshoe crab has the hard exoskeleton that is characteristic of arthropods. This shell acts to protect the crab from invasion by pathogens.

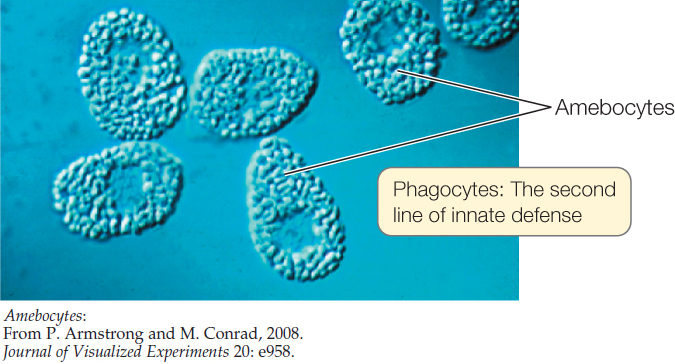

- Cells involved in innate defenses include phagocytes that bind to microbial pathogens, ingest them by endocytosis, and destroy their large molecules by hydrolysis. Amebocytes in the blood of the horseshoe crab fulfill this defensive role.

- Molecules that are toxic to invading pathogens are important in innate defense. The horseshoe crab has a wide array of such molecules that are released from cells in its blood. These molecules include peptides that disrupt the bacterial cell membrane, rendering it permeable; and peptides that bind to bacterial surfaces and cross-link them.

Studies of innate immunity, along with genome sequencing, have revealed that the recognition and activation phases of innate immunity evolved very early in animals. For example, animals as diverse as humans and fruit flies share a class of receptors, called Toll-like receptors, that participate in innate defense responses. In vertebrates, each Toll-like receptor recognizes and binds to a specific molecule that is found in a broad class of pathogens, such as a component of the bacterial cell wall. Binding sets off a signal transduction pathway that ends with the expression of genes for anti-pathogen molecules (FIGURE 39.1). This pathway exists in some form in many animal groups, including humans.

811

Mammals have both innate and adaptive defenses

In mammals and other vertebrates, the innate and adaptive defenses operate together, usually in sequence, as a coordinated defense system. We will focus on these defenses for the rest of the chapter. TABLE 39.1 gives an overview of innate and adaptive defenses during the course of an infection. Innate defenses are the body’s first line of defense; adaptive defenses often require days or even weeks to become effective.

The major players in adaptive immunity are specific cells and proteins. These are produced in the blood and lymphoid tissues and are circulated throughout the body, where they interact with almost all the other tissues and organs.

One milliliter of human blood typically contains about 5 billion red blood cells and 7 million white blood cells. Whereas the main function of red blood cells is to carry oxygen throughout the body, white blood cells (also called leukocytes) are specialized for various functions in the immune system (FIGURE 39.2). There are two major groups of white blood cells: phagocytes and lymphocytes. Phagocytes are large cells that engulf pathogens and other substances by phagocytosis. Some phagocytes are involved in both innate and adaptive immunity. In particular, macrophages and dendritic cells play key roles in communicating between the innate and adaptive immune systems. Lymphocytes include B cells and T cells, which are involved in adaptive immunity; and natural killer cells, which are involved in both innate and adaptive immunity.

812

Go to ANIMATED TUTORIAL 39.1 Cells of the Immune System

PoL2e.com/at39.1

CHECKpoint CONCEPT 39.1

- Make a table that compares innate and adaptive immunity.

- If you compared the genomes of an invertebrate (e.g., a crab) and a human with regard to the presence of genes for immunity, what might you find?

Now that we’ve seen a brief overview of innate and adaptive immunity, let’s look at some of the innate defenses that mammals have against invading organisms.