CHAPTER 10 INTRODUCTION

CORE CONCEPTS

10.1 Tissues and organs are communities of cells that perform a specific function.

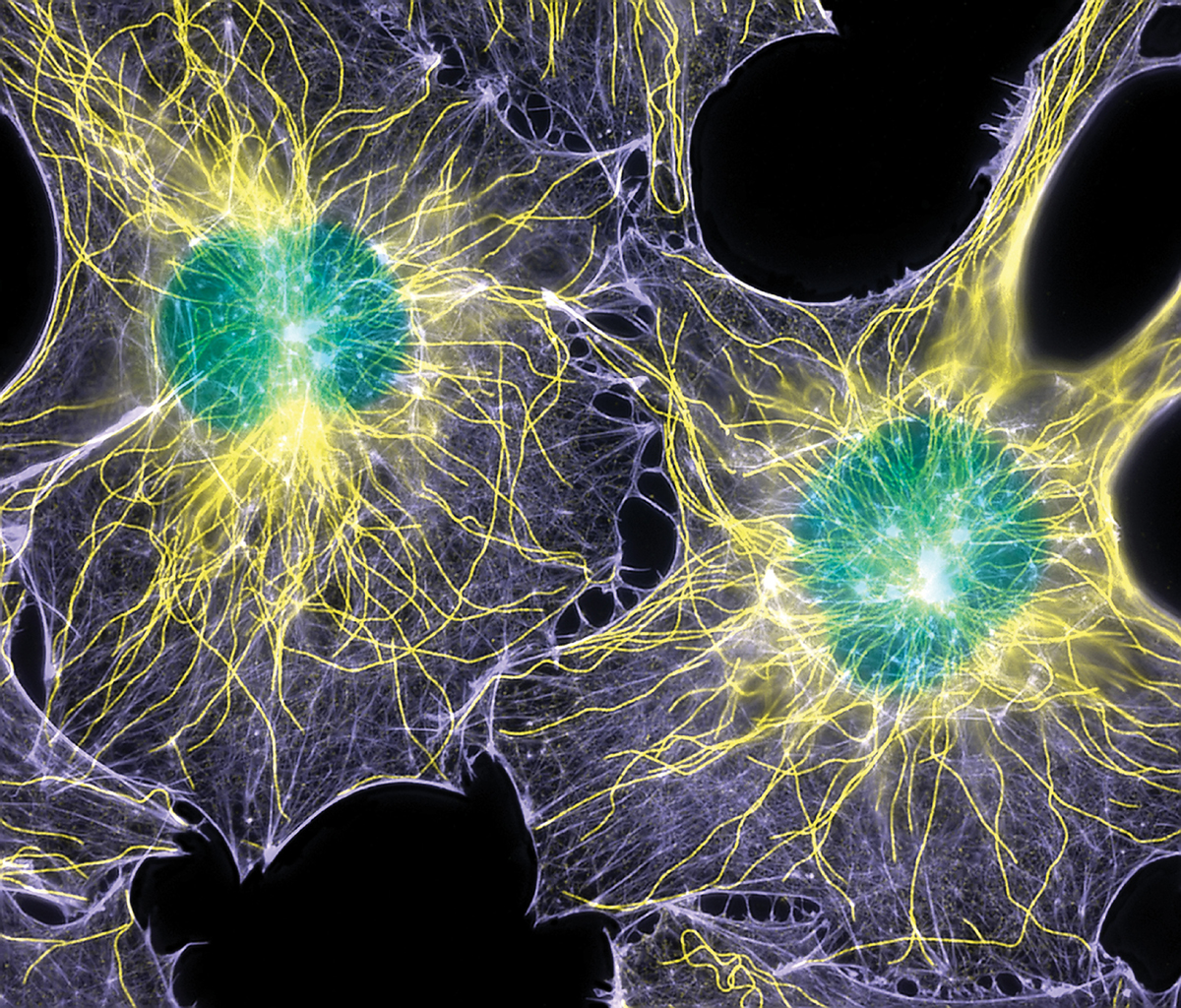

10.2 The cytoskeleton is composed of microtubules, microfilaments, and intermediate filaments that help to maintain cell shape.

10.3 The cytoskeleton interacts with motor proteins to permit the movement of cells and substances within cells.

10.4 Cells adhere to other cells and the extracellular matrix by means of cell adhesion molecules and junctional complexes.

10.5 The extracellular matrix provides structural support and informational cues.

A recurring theme in this book, and in all of biology, is that form and function are inseparably linked. This is true at every level of structural organization, from molecules to organelles to cells and to organisms themselves. We saw in Chapter 4 that the function of proteins depends on their shape. In Chapters 7 and 8, we saw that the function of organelles like mitochondria and chloroplasts depends on the large internal surface areas of the inner membrane of mitochondria and the thylakoid membrane of chloroplasts.

The functions of different cell types are also reflected in their shape and internal structural features (Fig. 10.1). Consider a typical red blood cell. It is shaped like a disk that is slightly indented in the middle, and it lacks a nucleus and other organelles (Fig. 10.1a). This unusual shape and internal organization allow it to be remarkably flexible as it carries oxygen in the bloodstream. Because it is able to deform readily, it can pass through blood vessels with diameters smaller than that of the red blood cell itself. Cells in the liver (Fig. 10.1b) that synthesize proteins and glycogen look very different from muscle cells (Fig. 10.1c) that contract to exert force. A neuron (Fig. 10.1d), with its long and extensively branched extensions that communicate with other cells, is structurally nothing like a cell lining the intestine (Fig. 10.1e) that absorbs nutrients.

As we saw in Chapter 9, cells often exist in communities, forming tissues and organs in multicellular organisms. Again, form and function are intimately linked. Think of the branching structure and large surface area of the mammalian lung, which is well adapted for gas exchange, or the muscular heart, adapted for pumping blood through large circulatory systems.

In this chapter, we look at what determines cell shape. We also examine the different ways cells adhere to one another to build tissues and organs, and see how this adhesion differs depending on the function of the cellular community. We also learn about the physical environment outside cells, which is synthesized by cells themselves and influences their behavior.