47.1 THE NICHE

As discussed in Chapter 46, the habitat occupied by a species is sometimes patchy in its distribution, like islands in a sea, and each patch can contain a number of different species. Distinct species can coexist within shared habitat patches because they use different resources or are active at different times. Nearly a century ago, the American ecologist Joseph Grinnell defined the niche as the sum of the habitat requirements needed for a species’ survival and reproduction. Later, ecologist Charles Elton redefined the niche as the role a species plays in a community, switching emphasis from the habitat to the population itself. By the middle of the twentieth century, ecologist G. Evelyn Hutchinson had combined these ideas, popularizing the concept of the niche as a multidimensional habitat that allows a species to practice its way of life. The niche is therefore determined by both physical (abiotic) parameters such as climate and soil chemistry and biological (biotic) factors based on interactions with other species.

47.1.1 The niche is the ecological role played by a species in its community.

The niche, then, reflects the interactions between populations and the physical and biological components of their surroundings. These interactions lead to adaptations, the products of natural selection. Adaptations in turn enable different species to coexist by exploiting different combinations of resources.

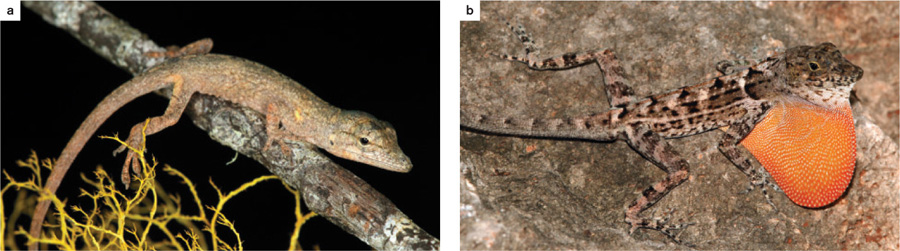

Anolis lizards, for example, hunt small insects in humid forests on Hispaniola and other islands in the Caribbean (see Fig. 46.19). The lizards have features of anatomy and physiology that determine, in part, where they can live. They cannot, for example, endure freezing temperatures. Within the forest, different Anolis species eat insects found in distinct parts of forest trees. That is, over time, they have evolved different adaptations for feeding as a result of competition for space and resources (Fig. 47.1). Anolis lizards, then, show that species whose niches overlap may diverge to minimize the overlap, a pattern called resource partitioning.

Interactions with predators such as lizard cuckoos and curly-tailed lizards further influence, and limit, the distributions of different species. Moreover, there is reason to believe that the ability (or inability) to disperse contributes to the distributions of individual species. For example, when Anolis species are introduced by accident or deliberately to places beyond their dispersal capabilities, they commonly thrive. Therefore, competition, predation, and dispersal are all factors that influence the distribution of species.

Species are commonly associated with a specific habitat, but “niche” and “habitat” are not interchangeable, as the niche refers to the ways that organisms respond to the resources and other species found within the habitat. American ecologist Eugene Odum summarized the distinction succinctly: The habitat is the organism’s “address” and the niche its “profession.” This distinction illustrates the dual nature of niches: They reflect where organisms occur and what they do there. The profession of Anolis lizards is insect-hunting; their addresses are the trees and shrubs of humid tropical America.

47.1.2 The realized niche of a species is more restricted than its fundamental niche.

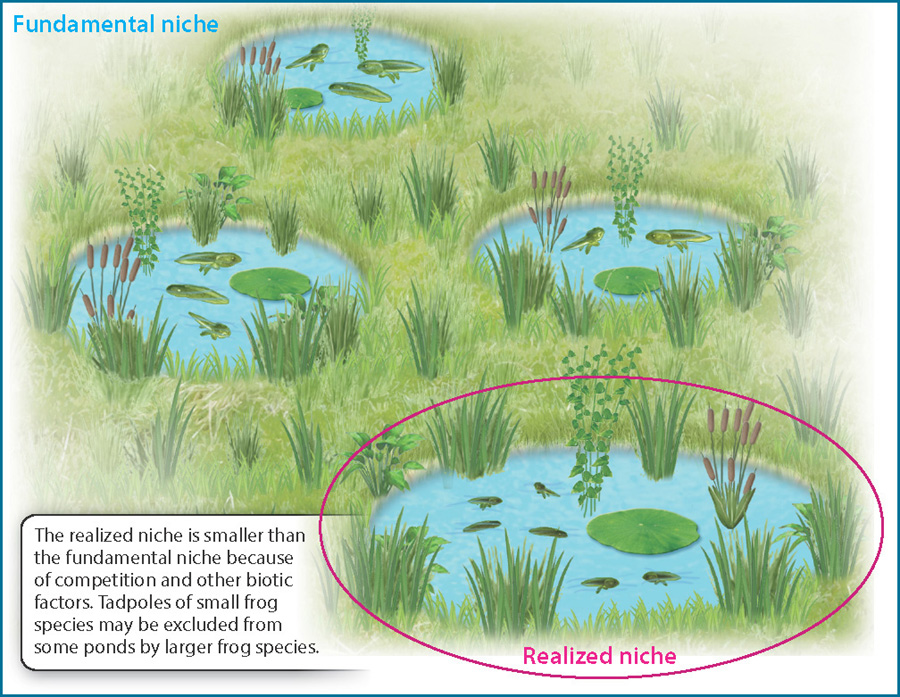

The fundamental niche comprises the full range of climate conditions and food resources that permits the individuals in a species to live. In nature, however, many species do not occupy all the habitats permitted by their anatomy and physiology. That is because other species compete for available resources, prey on the organisms in question, or influence their growth and reproduction, reducing the range actually occupied. This actual range of habitats occupied by a species is called its realized niche (Fig. 47.2).

For example, tree frogs can reproduce in small ponds near forests throughout eastern North America, their fundamental niche. However, tree frogs are excluded from ponds that also have larger frogs because the larger frogs eat most of the algal food available, limiting the tree frogs’ realized niche to ponds without larger frogs. Therefore, competition with other species—that is, interspecific competition—can determine the size of the realized niche.

Quick Check 1

Which is larger—the fundamental or the realized niche?