Chapter 1. Working With Data 3.2

Working with Data: HOW DO WE KNOW? Fig. 3.2

Fig. 3.2 describes Avery, MacLeod, and McCarty’s experiment determining the nature of the genetic material. Answer the questions after the figure to practice interpreting data and understanding experimental design. Some of these questions refer to concepts that are explained in the following two brief data analysis primers from a set of four available on LaunchPad.

- Experimental Design

- Data and Data Presentation

You can find these primers by clicking on the button labeled “Resources” in the menu at the upper right on your main LaunchPad page. Within the following questions, click on “Primer Section” to read the relevant section from these primers. Click on “Key Terms” to see pop-up definitions of boldface terms.

HOW DO WE KNOW?

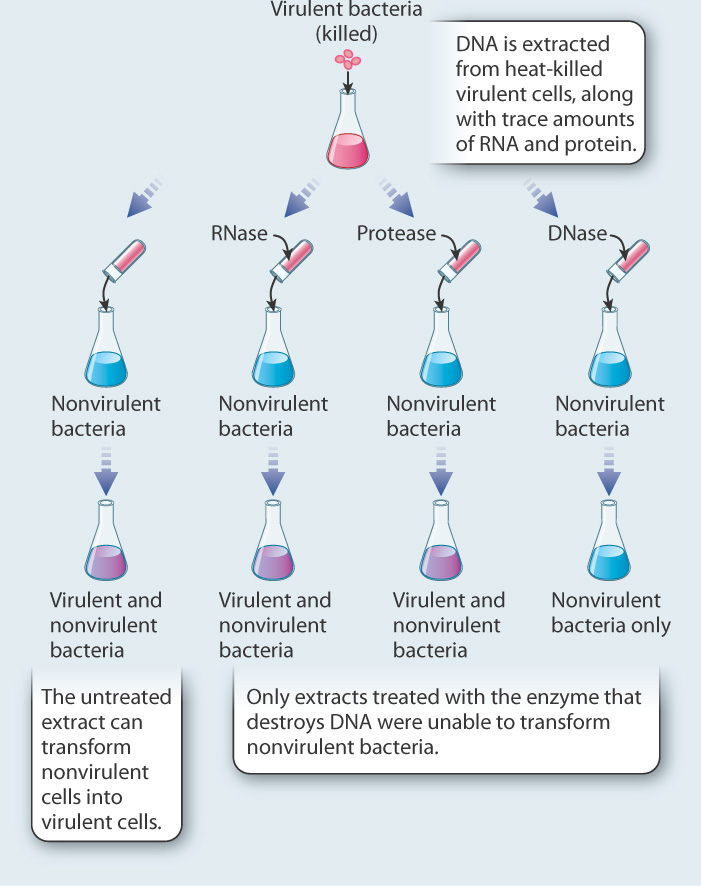

FIG. 3.2: What is the nature of the genetic material?

BACKGROUND Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty also studied virulence in pneumococcal bacteria. They recognized the significance of Griffith’s experiments (see Fig. 3.1) and wanted to identify the molecule responsible for transforming nonvirulent bacteria into virulent ones.

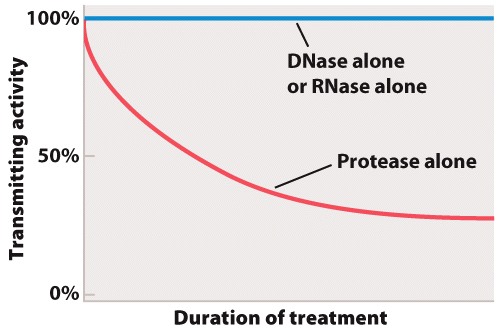

EXPERIMENT Avery, MacLeod, and McCarty extracted DNA from virulent bacteria, which allowed them to perform a series of tests and control variables. To identify what caused transformation, they treated the extract, which contained DNA as well as trace amounts of RNA and protein, with enzymes that destroyed one of the three molecules. Their hypothesis was that transformation would not occur if they destroyed the molecule responsible for it.

RESULTS

CONCLUSION DNA is the molecule responsible for transforming nonvirulent bacteria into virulent bacteria. This experiment provided a key piece of evidence that DNA is the genetic material.

FOLLOW-UP WORK These experiments were followed up by Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase, who used a different system to confirm that DNA is the genetic material.

SOURCE: Avery, O., C. MacLeod, and M. McCarty. 1944. “Studies on the Chemical Nature of the Substance Inducing Transformation of Pneumococcal Types.” Journal of Experimental Medicine. 79:137–158.

Certain diseases, including bovine spongiform encephalopathy ("mad cow disease") and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, are caused by an infectious agent whose nature was at first a mystery. Similar infectious agents are also known to cause a few traits in yeast. Under certain conditions, the infected yeast cells turn red. (Normal yeast cells are white.)

Question

Suppose you are studying a strain of red-colored yeast cells that you believe contains such an infectious agent. You first prepare an extract of the red cells that contains the cells’ DNA, RNA, and protein. Then you mix the extract with normal white cells to find out whether your extract can convert normal white cells to red. In this experiment, the experimental treatment is mixing the red cell extract with normal white cells. The proper control experiment would be to mix normal white cells with:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

| control | Operations or observations that are set up in such a way that the researcher knows in advance what result should be expected if everything in the study is working properly |

Experimental Design

Testing Hypotheses: Controls

Hypotheses can be tested in various ways. One way is through additional observations. There are a large number of endemic species on the Galápagos Islands. We might ask why and hypothesize that it has something to do with the location of the islands relative to the mainland. To test our hypothesis, we might make additional observations. We could count the number of endemic species on many different islands, calculate the size of each of these islands, and measure the distance from the nearest mainland. From these observations, we can understand the conditions that lead to endemic species on islands.

Hypotheses can also be tested through controlled experiments. In a controlled experiment, several different groups are tested simultaneously, keeping as many variables the same among them. In one group, a single variable is changed, allowing the researcher to see if that variable has an effect on the results of the experiment. This is called the test group. In another group, the variable is not changed and no effect is expected. This group is called the negative control. Finally, in a third group, a variable is introduced that has a known effect to be sure that the experiment is working properly. This group is called the positive control.

Controls such as negative and positive control groups are operations or observations that are set up in such a way that the researcher knows in advance what result should be expected if everything in the study is working properly. Controls are performed at the same time and under the same conditions as an experiment to verify the reliability of the components of the experiment, the methods, and analysis.

For example, going back to our example of a new medicine that might be effective against headaches, you could design an experiment in which there are three groups of patients—one group receives the medicine (the test group), one group receives no medicine (the negative control group), and one group receives a medicine that is already known to be effective against headaches (the positive control group). All of the other variables, such as age, gender, and socioeconomic background, would be similar among the three groups.

These three groups help the researchers to make sense of the data. Imagine for a moment that there was just the test group with no control groups, and the headaches went away after treatment. You might conclude that the medicine alleviates headaches. But perhaps the headaches just went away on their own. The negative control group helps you to see what would happen without the medicine so you can determine which effects in the test group are due solely to the medicine.

In some cases, researchers control not just for the medicine (one group receives medicine and one does not), but also for the act of giving a medicine. In this case, one negative control involves giving no medicine, and another involves giving a placebo, which is a sugar pill with no physiological effect. In this way, the researchers control for the potential variable of taking medication. In general, for a controlled experiment, it is important to be sure that there is only one difference between the test and control groups.