Chapter 1. Fundamentals of Scientific Inquiry in the Biological Sciences I

1.1

Marvin H. O'Neal III, Ph.D.

Deborah A. Spikes

Stony Brook University

BIO 204

1.2 Copyright

Copyright © 2014 by Joan M. Miyazaki, Marvin H. O’Neal III, Ph.D., Deborah A. Spikes, and Undergraduate Biology, Stony Brook University

Copyright © 2014 by Hayden-McNeil, LLC on illustrations provided

Photos provided by Hayden-McNeil, LLC are owned or used under license

All rights reserved.

Permission in writing must be obtained from the publisher before any part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system.

ISBN 978-0-7380-5926-6

Hayden-McNeil Publishing

14903 Pilot Drive

Plymouth, MI 48170

www.hmpublishing.com

Acknowledgements

This is our seventh year teaching Fundamentals of Scientific Inquiry in the Biological Sciences. BIO204 & BIO205/207 are sequential laboratories that focus on critical thinking and problem solving instead of memorization and the completion of cookbook activities. We have designed a two-semester curriculum that prepares students for scientific inquiry, experimental design, and use of modern instrumentation.

This new vision of laboratory science education was possible largely because of the dedication and hard work of Kelly O’Donnell, Roberta Harnett, and David Ruggerio in the Fall of 2007. We particularly wish to thank the curriculum committee members: Eugene Katz, John True, Neta Dean, Kate Dilger, and Daniel Apple for their valuable insight into the structure and design of these laboratories. This edition includes labs developed by M. Caitlin Fisher-Reid (Lab 2), Kelly L. O’Donnell (Lab 4), Center for Biomolecular Modeling at the Milwaukee School of Engineering (Lab 11), as well as a modified lab from BioRad Laboratories (Labs 13). They are not responsible for manuscript errors; we assume all responsibility of text and information accuracy.

This manual is not entirely an original text. Rather, it is the compilation of many years of dedicated service from exceptionally talented students, faculty, and staff. We are honored to have worked with them. Leo Shapiro, Paul Wilson, and R. Geeta made contributions to the invertebrates, systematics, and evolution lab exercises. Lev R. Ginzburg is responsible for the elegantly scripted RAMAS software used in the populations lab. The greenhouse lab would not be possible without Mike Axelrod and John Klump’s rock-solid competence and good humor. Zuzanna Zachar and Scott Rappel contributed valuable information for the PCR protocol. Michael Cressy delivered hours of editing and numerous creative contributions. This course would not function without the vast talents and efforts of the professional, administrative, and advising staff of Undergraduate Biology.

The teaching philosophy used in this manual was strongly influenced by Bill Dawes, Diane Ebert-May, Jackie Gennon-Brooks, Daniel Apple, Marjorie Kandel, and Barbara Panessa-Warren—over the years they have given us a great deal of creative and helpful advice. The Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the National Academies of Sciences Summer Institute on Undergraduate Education in Biology trained us and supported and encouraged our work to transform undergraduate science education to meet the needs of our students, the future scientists and professionals of the 21st century.

J. M. Miyazaki, D. A. Spikes, and M. H. O’Neal III

Stony Brook University

I would personally like to thank Joan Miyazaki and Debbie Spikes for their tireless work on this manuscript. Their visionary outlook and steadfast dedication to the education of Stony Brook students is extraordinary. It has been a true pleasure working alongside them on this exciting project. They continue to teach me a great deal. My heartfelt appreciation.

Marvin O’Neal

1.3 General Information

Course Objectives:

This course is designed to be an introduction to your career in the biological sciences and prepare you for upper division biology courses. The most critical aspect of this preparation is to develop scientific thought. In addition, you will be introduced to common laboratory practices and procedures, learn to conduct basic experiments, and practice experimental design using scientific reasoning. This course is divided into 13 labs, each of which falls into one of these categories: Laboratory Skills (5x), Managing Data (3x), Using Models (3x), and Scientific Communication (2x). For each lab there are learning goals and for every activity there are learning objectives. Use these goals and objectives as the backbone of your scholarship. They are the critical aspects within the course, the target for your preparation, the focus for your progress during lab, and the fundamental components used by faculty for all of the assessments within the course including quizzes, exams, competencies, and assignments.

College laboratories are training grounds for your future work environment, and it takes more than the mastery of a topic to succeed as a professional. You are expected to become a good observer, listener, oral communicator, reader, and writer in the biological sciences. To excel in this course, you will be required to understand and focus on the objectives of a project, think critically and creatively, categorize concepts, make connections, understand and use new terminology, and efficiently manage your time. You will use computers and statistics to collect and analyze data. At times, you will be called upon to be a leader, at other times to be an independent self starter, a team player, or a follower. You will also be required to present your work in both oral and written formats.

Upon completion of BIO204/5, we expect that you will have improved these 21st Century skills identified by The National Research Council in a recent report: adaptability, complex communication/social skills, nonroutine problem solving, self-management/development, and systems thinking.

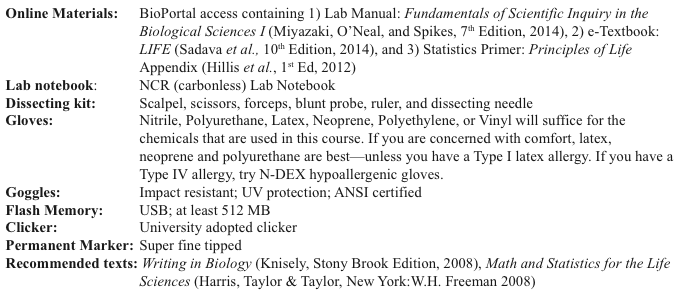

1.4 Required Materials

1.5 Students with Special Needs

If you have any condition, such as a physical, psychological, medical, or learning disability which will make it difficult for you to carry out the work for this course, or which will require extra time on examinations, please contact the staff in the Disabled Student Services Office (DSS), 128 Educational Communications Center, 632-6748. DSS will review your concerns and determine, with you, what accommodations are necessary and appropriate. Letters of notification should be addressed to Dr. Marvin O’Neal, Z=5110.

1.6 Use of Animals

Biology is the science of life, and learning biology requires the study of living organisms. In this course, you will be required to handle live plants and animals. You will also be expected to dissect preserved animals in some of the laboratory exercises. In every case, you are expected to handle all living organisms properly based on this manual as well as instructions from your instructor. If you have objections to these requirements, you must meet with Dr. O’Neal or submit in writing your objections within the first two weeks of the course.

1.7 Websites

1.8 Help

An entire team in Undergraduate Biology is here to help you. Follow these procedures to get your questions answered quickly and accurately:

- Ask your instructor for help. ALL instructors are required to hold one office hour each week per section. Feel free to speak with any instructor teaching this course. They are required to help all students taking BIO204. All office hours are open to any student taking BIO204.

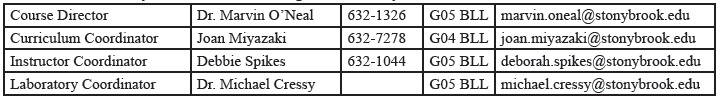

- Email faculty for help at our course email: introbiolabs@stonybrook.edu Your email will be answered by one of the following three faculty members:

3. Contact staff for specific help (see below):

1.9 Course Administration Roles

- Course Director: Dr. O’Neal is responsible for all course content, policies, and final letter grades.

- Coordinators: Joan Miyazaki, Deborah Spikes, and Michael Cressy, PhD are responsible for the biology lab curriculum, the learning facilities including the Biology Learning Labs, and instructors.

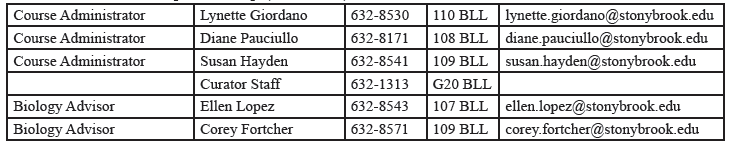

- Course Administrators: Lynette Giordano is responsible for add/drop forms, to change sections, or other problems relating to course registration. Sue Hayden is responsible for all student absences (see Attendance Policy on slide 10). Diane Pauciullo is responsible for the administration of exams including scantron issues and scheduling make-ups. Course administrators are not responsible for the policies implemented. You may see Dr. O’Neal for difficult issues or problems that remain unresolved.

- Instructors: This is a large course, but you should not feel shy or embarrassed to ask questions during lab or to come to posted office hours. Lab instructors hold one office hour per section every week in the Biology Learning Center (Room G10 of CMM/BLL); check the schedule posted on the door and on the course website in Blackboard. Dr. O’Neal’s office hours are also posted on the course website or you can visit G05 to schedule an appointment.

1.10 Laboratory Etiquette

- Do not bring food or drink into the labs. Students who choose to eat and drink in lab will be asked to leave and will receive a zero for their Lab Performance score.

- Computers are to be used for lab activities only. Students are not allowed to download programs, change shortcuts, or alter any settings on the lab computers. Please remember to log off of all lab computers and do not share accounts or passwords with fellow students. Students are welcomed to bring their own laptops or tablets to lab if they are used for professional activities. Unless asked to do so by your instructor, do not engage in any social media, video calls, games, or activities unrelated to laboratory.

- Full lab participation is expected. Your lab performance grade is based on participation during experiments and data collection, group involvement, inquiry, cooperation, and techniques. Tardiness will adversely affect your grade. Zeros are given for unexcused absences. Repeated unexcused absences (3 or more) will result in failure of the course.

- Electronic communication devices, including cellular phones, beepers, speakers, and headphones must be secured in a closed container (and not, for example, worn on a belt or around the neck) and must be turned off (and not, for example, simply set on vibration mode) during laboratory. If you have a cell phone or beeper that goes off during lab, you will be asked to leave and receive a grade penalty. You are NOT allowed to make calls or talk on a cell phone during lab.

- It is essential that you view the online lectures and demonstrations to understand the background, theory, and techniques for each lab. Students who perform best in this lab “actively” view the online material by taking clear and organized notes and recording any questions that you have about course material. These should be brought to the attention of your instructor prior to lab.

- Online lectures are always available to you; there is no excuse for missing lecture information. If you fall behind, do not wait to catch up. This course covers too much information to learn by cramming. If you run into personal problems that make it difficult to keep up, see Dr. O’Neal as soon as possible to work something out.

- If you are not getting the grades you want, see your instructor immediately, and Dr. O’Neal if necessary, to work out a plan to improve your performance. Do not walk into Dr. O’Neal’s office at the end of the semester requesting that your grade be changed because you need a better grade to achieve your career goals. At this point, it will be too late.

1.11 Attendance Policy

Lab attendance is required. You are expected to attend and participate in every lab for the full period. If you miss 3 normally scheduled labs, for any reason (excused or unexcused), you will automatically fail this course. When in lab, you should be working. Lab participation and performance (professionalism, technical skills, and analytical skills) are used to determine your letter grade. Tardiness is not acceptable and incurs an automatic performance grade penalty of no credit. Quizzes are given throughout lab and you are responsible to answer questions at any time during lab--no make-up quizzes will be given.

Excused Absences: An unavoidable absence from lab which is due to sudden illness or a death in the family may be excused. Documentation must be submitted to the Course Administrator, Susan Hayden (Office: 109 CMM/BLL, 632-8541). Students are only excused from the performance and quiz component for that week. Excused students are still responsible for all written work. Written assignments are due within one week of returning to lab (or two days for summer session). There are no make-up quizzes. For excused absences, the quiz grade will be calculated as an averaged percent of the remaining quizzes. Exams and practicals must be taken at regularly scheduled times. Requests to make up an exam should be submitted, in writing, to the Course Director and should be accompanied by an excused absence and written documentation from Susan Hayden. Permission to make up exams and practicals will be decided on a case by case basis.

Note

If you have an official, pre-scheduled university event such as an athletic competition or an exam conflict in another class, then you should schedule make-up laboratories by the second week of classes. Last minute requests will not be honored.

Make-up Laboratories: There are no make-up labs. In rare circumstances, you may be permitted to attend another lab section within the regular lab schedule “if” space is available, you bring in a valid excuse, AND are approved by the Course Administrator, Susan Hayden (Office: 109 CMM/BLL, 632-8541). A “Bio Student Absence Form” must be completed, signed by the Course Administrator, and presented to the Lab Instructor of the make-up lab section that you attend. Making up a laboratory does not negate an unexcused absence.

Unexcused Absences: Zeros will be given for all lab work including quizzes, lab performance and in-class activities if you are absent (unexcused). Work that is missed due to lateness will not be excused. Lab work that is due on the day of an unexcused absence should be submitted electronically by the beginning of lab to be accepted as “on time.” At most, half credit will be given for all written work (such as lab exercises, worksheets, and reports) that are assigned on the day of the unexcused absence.

Calculating Penalties for Late Work: For assignments to be accepted on time, they must be submitted by the beginning of lab before the quiz on the day that they are due. Assignments handed in late will be penalized 10% of the total point value per day; except for late work due to an unexcused absence (see above). For example, an assignment worth 100 points that is one day late will receive a grade no higher than 90, 2 days late, no higher than 80, etc. Assignments are graded based on a rubric and the percent score is multiplied by the late penalty score. If you received 78% based on the rubric and were two days late, your final grade would be 62.4%. No assignments will be accepted more than 7 days after the due date (or two days for summer sessions).

1.12 Academic Integrity

Academic honesty and integrity are fundamental to all aspects of academic and scholarly work. Therefore, consistent with University policy, we view any form of academic dishonesty with utmost seriousness and will take the necessary steps to protect the academic integrity of this course.

- Definition: “Academic dishonesty includes any act that is designed to obtain fraudulently, either for oneself or for someone else, academic credit, grades, or other recognition that is not properly earned or that adversely affects another’s grade.” The following represents examples of this but does not constitute an exhaustive list:

- Cheating on exams or assignments by the use of books, electronic devices, notes, or other aids when these are not permitted including collusion or copying from another student.

- Submitting the same paper in more than one course or repeatedly within the same course without permission of the instructors.

- Plagiarizing: copying someone else’s writing or paraphrasing it too closely, even if it constitutes only some of your written assignment.

- Falsifying documents or records related to credit, grades, status (e.g., adds and drops, P/NC grading), or other academic matters.

- Altering an exam or paper after it has been graded in order to request a grade change.

- Stealing, concealing, destroying, or inappropriately modifying classroom or other instructional material, such as posted exams, laboratory supplies, or computer programs.

- Preventing relevant material from being subjected to academic evaluation.

- Action: The strongest action allowed by University guidelines will be followed for each incident. Without exception, all incidents will be submitted in writing to the University Academic Judiciary Committee.

- Result: All students found guilty of academic dishonesty are required to take the University’s course on academic integrity (the “Q” course); however, additional penalties may also be levied. These penalties could range from receiving a “0” on an assignment or exam, failure of a course, and possibly suspension or expulsion from the University. Once reported, students are subject to the ruling and findings of the Academic Judiciary Committee. Information about the procedures for hearings and other functions (including appeals) can be found on the website referenced below as well as in the Office of Undergraduate Academic Affairs (www.stonybrook.edu/uaa/).

1.13 Student Grades

Check the Blackboard course website regularly for information regarding grade components, administrative changes, lab instructor communication, and course updates.

Quizzes will be given at the beginning (Pre-Quiz) and the end (Post-Quiz) of each laboratory utilizing the university-approved clicker. Pre-Quizzes are designed to determine if you have prepared for lab by testing content from BioPortal, the online lecture (vodcast), and lab manual. You are encouraged to take notes in your lab notebook, which can be used during the Pre-Quiz. Notes will NOT be allowed during Post-Quizzes. No make-up quizzes will be given.

BioPortal Quizzes should be taken before arriving to lab to help master the biological content necessary to understand the laboratories. This material may be a review from prerequisite courses or new material specific to the upcoming lab. Reading assignments are included for each lab and are linked to quesitons to help you prepare for lab.

Lab Performance is based on each week’s preparation (submitted copy of your notebook) and participation during experiments, data collection, group discussion, and scientific inquiry. Full participation is expected and your response to instructor questions during lab will also affect this grade. At the end of each lab, at least one group will be required to discuss their findings for that day with the class. Poor performance will result from tardiness (-2), lack of prelab (-2), poorly answered questions (-1), etc. Unexcused absences will result in a zero. Repeated unexcused absences (3 or more) will result in failure of the course.

Lab Assignments will be graded based on a uniform rubric across all sections. All written assignments are due before the start of the Pre-Quiz. See “Calculating Penalties for Late Work” to determine how your grade will be calculated. The official time is the Coordinated Universal Time of the U.S. Naval Observatory’s cesium fountain atomic clocks corrected for Eastern Standard Daylight Savings. This time is broadcasted continuously from NIST radio station WWVB at 60 kHz (with phase modulation time code protocol) and WWV(H) radio stations at 2.5, 5, 10, and 15 MHz.

Exams include the Competency (50 pts), Midterm (100 pts), and Final (150 pt) NO ONE WILL BE ADMITTED LATE TO THESE EXAMS. We are forced to adhere strictly to this policy to deter cheating schemes. Even if you have a valid excuse, you will not be allowed to take the exam if you come late. Do not risk getting a zero for an exam! If you have a valid, documented excuse, see Susan Hayden immediately. If you wish to protest a question or the answer on an exam, then your reasoned argument must be submitted in writing to the course director on the next business day following the posting of the answer key of exam.

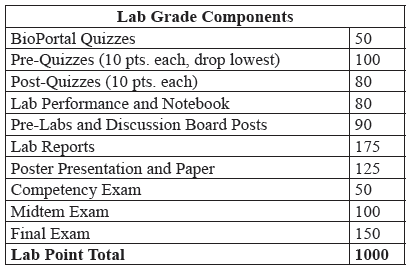

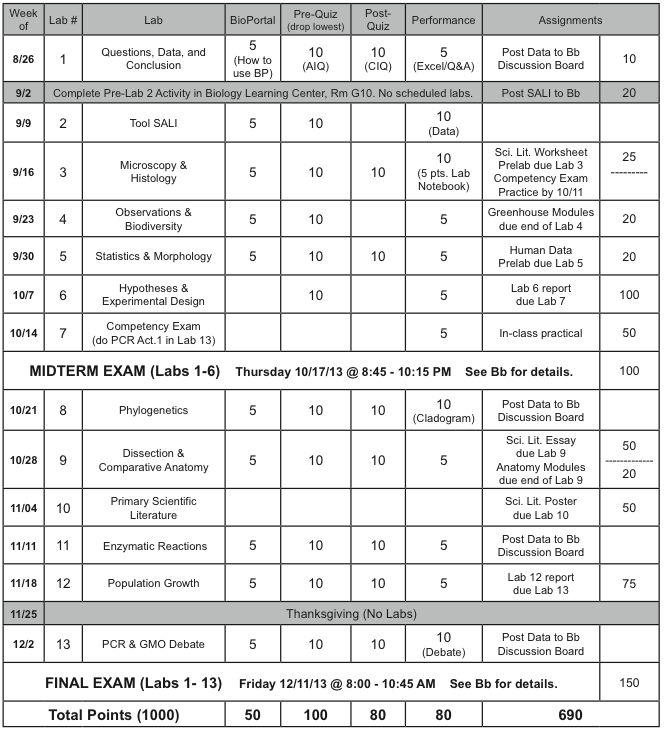

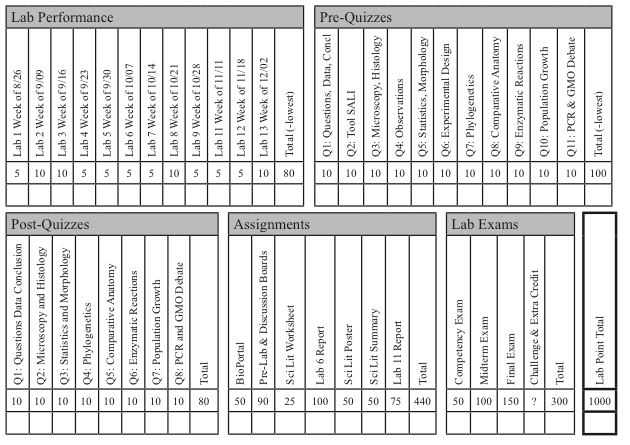

The following is a summary of the above mentioned components totalling 1000 points:

Course Schedule

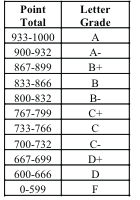

Letter Grades are assigned by the Course Director at the end of the semester after all of the points have been submitted by each instructor. Letter grades are based on your final point total. The table to the right will help you determine the MINIMUM letter grade that you will receive based on accumulated points. However, we sometimes curve the class based on the performance of individual sections due to variance in the instructors. Therefore, your letter grade may be higher than this scale (for example, in BIO 204 fall 2008, a score of 875–1000 received an “A” and the “F” range was 0–499 points). Historically, the average letter grade in this course has been approximately a C+. While course grades are commonly curved up, they are never curved down. If every student accumulates at least 933 points by the end of the semester, then everyone will receive an “A”. If a Challenge Exam and/or Extra Credit is/are given, then the letter grade will still be calculated based on the 1000 point scale and not the percent score, even if the point total exceeds 1000 points.

Use the guide below to monitor your progress in BIO 204:

1.14 Laboratory Notebook

Track the progress of your projects using a notebook with NCR paper. Research notes, descriptions, data collection, ideas, and reflections, are fundamental to science. You will be asked to turn in the copied page of these notes at the end of each lab, so keep them neat and up to date. These will contribute to your performance grade.

Expected Content: Notebooks are records of work accomplished in lab and serve as future reference for protocols used; details of instrumentation use; roles and credit for work done by group members.

- Table of Contents — first two pages

- Your name, group members, group roles and date — on each page

- Numbers — Data measurements, counts, etc. in data tables and graphs

- Visuals — Sketches, figures

- Text — Write purpose statements, descriptions, and legends. Insights described, quality of questions, additional hypotheses, evidence of progress are indicators of critical thinking and depth of understanding.

- Organization and Clarity — Legibility and neatness as needed to retrieve information efficiently

- Pre-lab content — Vodcast and reading notes with answers to discussion questions. These may not be handed in as typed pages. Lab notebooks can be used during Pre-Quizzes, not Post-Quizzes.

- Academic Integrity — Copying is not acceptable for graded exercises.

Grading Standards for Lab Notebook Evaluations:

- Excellent — Notes are thorough and informative. Measurements recorded in tables (with units), clear and easy to follow, excellent observations, labeled graphs and clear figures with legends, group contributions (roles) included. Insights into understanding or future investigations demonstrate critical thinking and depth of understanding. Details of essential information included (e.g., locality for field work). Individual contributions to group report: all individuals contributed according to their roles. SII for group and lab activities are clearly recorded. Contributions, strengths, areas for improvement and insights into team contribution and lab activities.

- Good — Notes are adequate reference for future use. Notes are similar in most ways to the excellent category above, graphs and figures OK, notes acceptable, details OK, readable, neat enough. Some important information is missing or hard to locate. SIIs are adequate.

- Needs Improvement — Most important information recorded, but overall notes, graphs and figures are lacking in detail, clarity and organization making it difficult to follow this record of lab activities. SIIs are weak or superficial.

- Failing — Notes are minimal and uninformative—not useable as a reference for future investigations. Sloppy or wasted space. Important information such as name, date, team members, missing. Sketches have no labels or references. SII weak or missing.

Team Roles: Rotate weekly—While all members are responsible for carrying out lab activities, each role carries specific responsibilities. Refer to Appendix A for complete descriptions for each team role for a group of 4 students: leader, technician, analyst, and recorder (in groups of 3 students, the leader is also the analyst).

1.15 Habits of Effective Students

written by Sherryl Broverman

Success is a matter of choice. While obviously not all are born with equal abilities, educators know that those students who achieve high grades do so mostly because of their learning habits. This includes attending all classes and taking good notes, but it also goes much deeper than this. In fact, there is a culture of learning, and, like all cultures, it can be explored and assimilated by those who value it.

Taking Responsibility

The number one attribute of a successful student is taking personal responsibility for your own education. You must realize that you have more to benefit than anyone else does by taking control of your undergraduate experience. This means:

- Obtaining and reading the syllabus

- Doing the readings prior to class

- Viewing all lectures

- Actively listening during lecture

- Re-reading or rewriting your notes in the evening

- Preparing for lab

- Understanding lab objectives

- Fully participating during lab

- Following up on all lab assignments

This sounds simple and self-evident, but many students set themselves up for failure by not doing even these basic things. Clearly all these things take time and some sacrifice of social activities. However, every learner must do a personal cost-benefit analysis of how they spend their time and what they hope to achieve from their education. Successful students realize that the payoffs can be enormous. Another aspect of taking personal responsibility is realizing that learning does not occur in a vacuum. This means identifying all the resources available to help you learn and achieve success - and using them! The number one resource around you is people: classmates, teaching assistants and faculty. Your peers are wonderful, and often under-utilized, assets. One hundred people listening to the same lecture often write down different things. If you compare notes with each other (e.g., identifying major concepts and filling in gaps), then you all will benefit. For those questions not resolved by discussions with peers, seek out an instructor, whether graduate student or faculty. Besides it being their job, the majority of people involved in education LIKE to teach and look forward to assisting others in learning. After reviewing your notes, bring them to office hours with questions. Traditionally, students who interact more with instructors/faculty do better on exams.

There are, of course, other resources available to students besides people. The primary one should be this course’s accompanying texts. If an unknown word or term is used during lecture, look it up in the index or examine the definition in the glossary. A capable student also identifies related resources whether they are library references, CD-ROMs, or web sites. A caution about web sites: not all information on web sites has been through the critical review process which is so essential to good science. There is a great deal of misinformation on the web, so beware!

Goal Setting

Another important feature of a successful student is they know how to set personal goals and how to develop strategies for reaching them. The first step in doing this is to set specific goals rather than vague ones; i.e., instead of saying, “I will study tonight”, say “I will read a chapter in chemistry and do ten math problems tonight.” It is also useful to take a long term goal (“I want to get into graduate school”) and break it down into concrete short term goals (“I want to get an A or B in biology, so I will do the reading and homework assignments before each class.”). Goals differ from wishes in that they are attainable by personal action. The best goals define the action needed to accomplish them. Most importantly, goals should be realistic and self-chosen, which means some self-awareness is necessary to create them. Only with an attainable and personally valuable goal will you avoid frustration and disappointment.

By following the guidelines presented here you can begin to develop a culture of learning. By doing so, you won’t just enhance your performance as an undergraduate, the majority of the skills listed above (taking personal responsibility, budgeting time, identifying resources, setting goals, etc.) will assist you in achieving success in all walks of life.

1.16 The Importance of Collaboration in Science

Science has always been a cooperative discipline; each new piece of knowledge must be created from the existing knowledge and will in turn lead to even more breakthroughs. Education, on the other hand, has traditionally been something you do on your own: attending lecture, taking notes, studying for tests, sometimes working with a partner in a lab. The skill of cooperating with a team in an organized way to achieve a common goal is fast becoming commonplace in all areas of life, including business and industry, health care, public service, government, and especially education.

Undergraduate students of biology have been discovering the many benefits of teamwork. Collaborating with others allows each of you to accomplish more work, and a higher quality of work, in a shorter period of time. Teamwork allows the development of interpersonal skills that will benefit you in all aspects of your life. Also individuals in a team benefit by teaching others new skills, learning to negotiate, exercising leadership, working with diversity, and benefiting from the knowledge and skills of others. Students who have completed a semester of group work often say they learned more and learned faster by discussing what they are learning with teammates. It is for reasons such as these that the activities in this course have been designed to incorporate the teamwork process.

As you will realize from your experiences in this course, an effective teamwork process involves a great deal more than simply putting people together in a group with a task to work on. A very valuable way of approaching problems in a group is to have each member of the group perform a defined role. In Appendix A are roles that can help build a strong team and allow you to complete high quality work in a shorter period of time.