17.4 Organizational Behavior

Organizational behavior (OB) focuses on how the organization and the social environment in which people work affect their attitudes and behaviors. Job satisfaction is the attitude most thoroughly researched by I/O psychologists, with over 10,000 studies to date. The impact of leadership on attitudes and behaviors is another well-researched OB topic. We will examine both of these topics here.

Job Satisfaction

Lucy and Jane are both engineers who work in the same department of the same company. Lucy is almost always eager to get to work in the morning. She feels that her work is interesting and that she has plenty of opportunities to learn new skills. In contrast, Jane is unhappy because she feels that she doesn’t get the recognition she deserves at work. She also complains that the company doesn’t give enough vacation time to employees and that it provides inadequate benefits. Jane can’t think of many good things about her job. She’s even beginning to feel that her job is negatively affecting her personal life.

Fortunately, Lucy is more typical of U.S. workers than Jane is. A recent International Herald Tribune/France 24/Harris Interactive survey reported that at least two-thirds of U.S. workers say they are satisfied with the type of work they do and their pay (Harris Interactive, 2007).

Several approaches have been used to explain differences in job satisfaction. An early approach was based on a discrepancy hypothesis, which consists of three ideas: (1) that people differ in what they want from a job; (2) that people differ in how they evaluate what they experience at work; and (3) that job satisfaction is based on the difference between what is desired and what is experienced (Lawler, 1973; Locke, 1976). Lucy and Jane, for instance, may not only want different things from their jobs; they may also make different assessments of the same events at work. Although their supervisor may treat them in the same encouraging manner, Lucy may see the boss’s encouragement as supportive while Jane may view it as condescending. As a result, one perceives a discrepancy between desires and experiences, whereas the other does not.

discrepancy hypothesis

An approach to explaining job satisfaction that focuses on the discrepancy, if any, between what a person wants from a job and how that person evaluates what is actually experienced at work.

Subsequent research supported the discrepancy hypothesis. For example, negative discrepancies (getting less than desired) were found to be related to dissatisfaction. Interestingly, positive discrepancies (getting more than desired) were also related to dissatisfaction in some cases (Rice & others, 1989). As an example, you might be dissatisfied with a job because it involves more contact with customers than you wanted or expected.

However, other factors have been identified as contributing to job satisfaction. The 2007 SHRM Job Satisfaction Survey lists compensation, benefits, job security, work–

Leadership

I/O psychologists have invested extensive energy searching for the formula for a great leader. Leaders are those who have the ability to direct groups toward the attainment of organizational goals. There are several classic theories that shaped our early views of leadership. The trait approach to leader effectiveness, one of the earliest theories, was based on the idea that great leaders are born, not made. This approach assumed that leaders possess certain qualities or characteristics resulting in natural abilities to lead others. Some examples of these “natural-born” leaders included John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Nelson Mandela. A large number of traits—such as height, physical attractiveness, dominance, resourcefulness, and intelligence—were examined for connections to leader effectiveness. A substantial amount of trait research was initially conducted, much of it showing little connection between personal traits and leader effectiveness (Hollander & Julian, 1969; Stogdill, 1948). Recent trait research continues, with some studies identifying traits, such as emotional intelligence, that can have a positive impact on employee behavior (Rego & others, 2007). Unfortunately, to date, trait researchers still haven’t found a comprehensive “leadership recipe.”

trait approach to leader effectiveness

An approach to determining what makes an effective leader that focuses on the personal characteristics displayed by successful leaders.

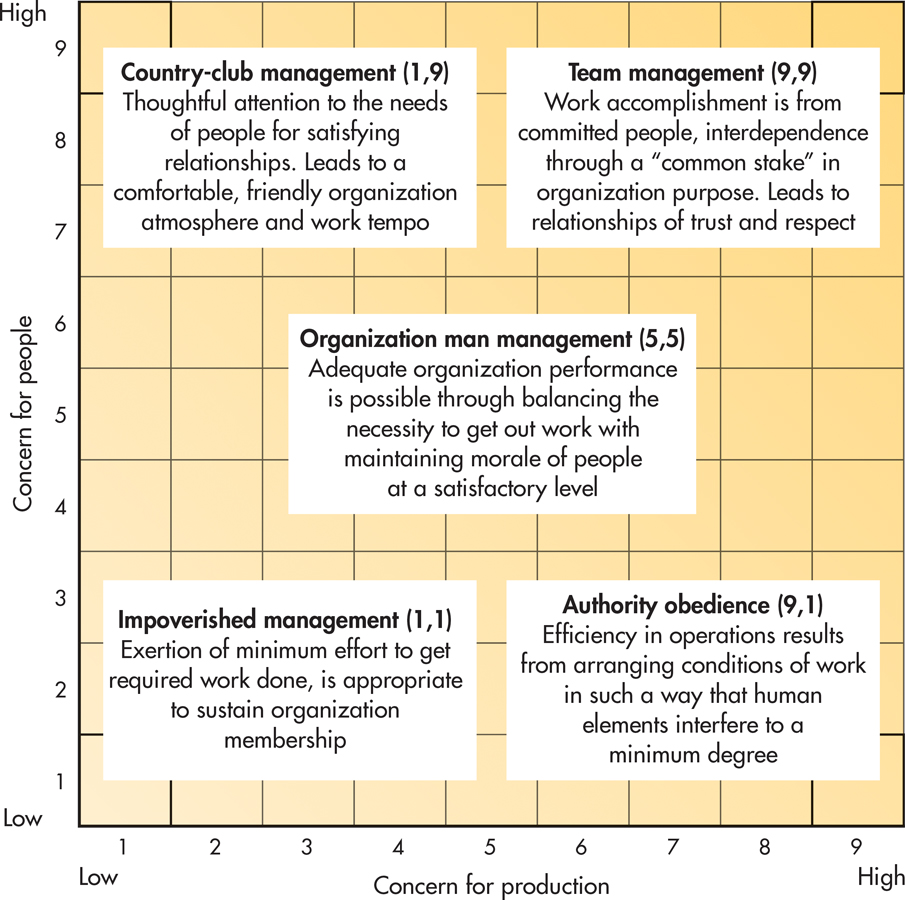

Consequently the emphasis turned to another explanation for effective leadership. Could leaders be made? Could they be taught “leadership behaviors” that would make them more effective? Researchers exploring the behavioral theories of leader effectiveness reasoned that the behaviors of effective and ineffective leaders must differ. In 1960, Douglas McGregor published The Human Side of Enterprise, in which he outlined Theory X and Theory Y, creating the view that leaders were polarized into those who either cared about the job (X) or cared about the people (Y). Research on these two dimensions found that ineffective managers focused on only one dimension. For example, if your boss cares only about production, then your job satisfaction and morale may decline. In contrast, if your boss is “all heart” but holds no production expectations, your job satisfaction may be high but your productivity low (Bass, 1981; Locke & Schweiger, 1979). A few years after McGregor’s book was published, Robert Blake and Jane Mouton expanded upon the theory with their Managerial Grid, claiming it was possible to care about both productivity and people. By placing these two variables on a grid, they could plot five primary managerial styles (see FIGURE B.4). A manager with low ratings in both areas was labeled (1,1), an “Impoverished Manager.” In contrast, one scoring highest on both concern for production and concern for people was labeled (9,9), the “Team Leader” (Blake & Mouton, 1985).

behavioral theories of leader effectiveness

Theories of leader effectiveness that focus on differences in the behaviors of effective and ineffective leaders.

Next to evolve were situational (or contingency) theories of leadership, which stated that there was no one “best” way to manage every employee. These theories claimed that good leadership skills depend, or are contingent upon, various situational factors, such as the structure of the task and the willingness of the follower. Accordingly, the best leaders will utilize the leadership style most appropriate for the employee and the situation at hand. These theories tended to be complicated, but they did a better job of explaining leader effectiveness than either the trait approach or behavioral theories.

situational (contingency) theories of leadership

Leadership theories claiming that various situational factors influence a leader’s effectiveness.

Much of the research on leadership emphasized the impact of leaders on followers, ignoring the fact that followers also influence leaders. In contrast, a modern approach, called the leader-member exchange model, emphasizes two types of relationships that can develop between leaders and employees. Positive leader–

leader–member exchange model

A model of leadership emphasizing that the quality of the interactions between supervisors and subordinates varies depending on the unique characteristics of both.

More recently, leadership research has focused on topics such as transformational versus transactional leadership, charismatic leadership, shared leadership, and servant leadership, which is highlighted in the In Focus box below, “Servant Leadership: When It’s Not All About You.” Although researchers have yet to find the formula for a perfect leader, they have shed a bright light on the optimal conditions for leadership development.

IN FOCUS

Servant Leadership: When It’s Not All About You

What do Jeffrey Skilling, Bernard Ebbers, and Dennis Kozlowski have in common? They were all entrusted with leadership positions for corporate giants such as Enron, WorldCom, and Tyco. They also failed miserably in their posts as leaders. Ebbers, former CEO of WorldCom, was convicted of fraud and conspiracy and is said to have been personally responsible for the $11 billion loss to WorldCom investors. Formerly CEO of the now-defunct Enron, Jeffrey Skilling went to federal prison after having been found guilty of fraud and insider trading in one of America’s most notorious cases of corporate corruption. Kozlowski, too, went to prison, convicted of misappropriating $400 million of his company’s funds while he was CEO of Tyco.

All three of these individuals are what some researchers call narcissistic leaders. Research on selfish leadership demonstrates that narcissistic leaders display certain behaviors that make them more likely to take self-serving risks, inconsiderate of the role of stewardship placed upon them as leaders. One study found that such CEOs focus on themselves at the expense of organizational awareness (Chatterjee & Hambrick, 2007). By featuring their pictures, their names, and their stories on organizational literature, these CEOs demand all the attention, instead of sharing the spotlight with the hardworking “stagehands” behind the scenes.

If you’ve ever known a highly narcissistic individual, it was probably not by choice. As employees, we like to receive recognition and at least some acknowledgment that what we do is valued. Selfish leaders are unable to fill our needs because of their own need to have their egos stroked on a constant basis. Their belief system includes self-promoting ideas such as, “I am, by far, the most valuable person in this organization,” or “Leadership is a solo endeavor, not a group activity” (Chatterjee & Hambrick, 2007).

Enter the servant leader. In 1970, Robert Greenleaf, a retired AT&T corporate executive, was the first to use the term servant leader. He defined a servant leader as one who makes service to others, including one’s employees, the foremost leadership objective. Greenleaf believed that servant leaders are successful because of their sincere commitment to helping their followers succeed. They invert the organizational chart, placing employee needs above their own (Zandy, 2007). Employee centeredness, where the leader’s focus is on employee concerns, allows leaders to roll up their sleeves during crunch times. Most important, servant leaders’ humility allows them to recognize their employees as emerging leaders who need organizational support to reach their potential. Humility is the servant leader’s most prominent trait, unlike the narcissistic leader’s self-promotion.

Warren Buffett, one of the richest men in the world, exemplifies servant leadership. Buffett’s financial success often overshadows his generous spirit and humble demeanor; he has pledged to give 99% of his $47 billion fortune to charity. As a leader, he values the development of his staff and colleagues, often acknowledging his own mistakes before announcing their successes. His ethical transparency allows everything to be disclosed. Buffett says, “You don’t need to play outside the lines. You can make a lot of money hitting the ball down the middle” (George, 2006). If only Skilling, Ebbers, and Kozlowski had followed his lead.