10.2 Gender Stereotypes and Gender Roles

KEY THEME

Gender-role stereotypes are the beliefs and expectations that people hold about the characteristics and behaviors of each sex.

KEY QUESTIONS

How do men and women compare in personality characteristics and cognitive abilities?

How do men and women compare in terms of sexual attitudes and behaviors?

Think Like a SCIENTIST

Are you more likely to associate men with science? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about Gender Stereotypes.

The beliefs people have about the typical characteristics and behaviors of each sex are referred to as gender-role stereotypes. In our culture, gender-role stereotypes for men and women are very different. Women are thought (and expected) to be more emotional, nurturing, and patient than are men. Men are thought (and expected) to be more aggressive, decisive, and mechanically minded than are women (Rudman & Glick, 2008, 2012). People often assume that gender stereotypes are derogatory toward women. In the United States, however, both men and women view the female gender-role stereotype more positively than the male gender-role stereotype (T. L. Lee & others, 2010). Still, psychologists Peter Glick and Susan Fiske (2001; 2003) argue that accepting positive stereotypes of women can produce a type of prejudice called benevolent sexism. While benevolent sexism is more socially acceptable than hostile sexism, it can contribute to gender inequality (Sibley & Perry, 2010; Glick & Fiske, 2012). As Glick and Fiske observe, “Characterizing women as pure creatures who ought to be protected, supported, and adored … implies that they are weak and best suited for conventional gender roles.”

gender-role stereotypes

The beliefs and expectations people hold about the typical characteristics, preferences, and behavior of men and women.

What about gender-role stereotypes in other cultures? In a survey of more than 25 cultures, psychologists John Williams and his colleagues (1999) and Deborah Best (2001) discovered a high degree of agreement on the characteristics associated with each sex (see TABLE 10.1). In general, the characteristics associated with males tended to be stronger and more active than the characteristics associated with females. In countries such as Japan, South Africa, and Nigeria, characteristics associated with the male stereotype were viewed more favorably than were characteristics associated with the female stereotype. However, the reverse was true in other countries, such as Italy, Peru, and Australia.

Psychologists John Williams and his colleagues (1999) and Deborah Best (2001) surveyed the characteristics commonly associated with men and women in 25 countries. Most of these characteristics are listed here. Overall, characteristics associated with the male stereotype tended to be more active and stronger than the characteristics associated with the female stereotype.

Gender Stereotypes Across Cultures

| Characteristics Associated with Males | Characteristics Associated with Females | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | Daring | Rude | Affectionate | Dependent | Sensitive |

| Adventurous | Dominant | Self-confident | Anxious | Emotional | Soft-hearted |

| Aggressive | Energetic | Stern | Attractive | Fearful | Submissive |

| Ambitious | Forceful | Strong | Charming | Fussy | Talkative |

| Courageous | Independent | Tough | Complaining | Meek | Timid |

| Cruel | Logical | Unemotional | Curious | Mild | Weak |

| Source: Research from Williams & others (1999). | |||||

Gender-Related Differences: THE OPPOSITE SEX?

Are men and women radically different? It’s a common theme in some self-help books, such as the series of books inspired by Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus (Gray, 2012).

When psychologists scientifically investigate the issue of gender differences, what do they find? Are men and women fundamentally different in all areas of their lives, as is often claimed in the popular media? Not really. In many aspects of behavior, including social, personality, and cognitive aspects, men and women are very similar (Gerber, 2009; Guimond, 2008; Hyde, 2007). And despite the claims of popular self-help books, men and women do not tend to perceive themselves as being diametrically opposite (Barnett & Hyde, 2001). Indeed, prominent researchers have encouraged a focus on gender similarities as well as differences. As Janet Hyde (2014) points out, the emphasis on gender differences can overshadow the far greater number of gender similarities.

Nevertheless, there are some significant differences between the sexes, even beyond the obvious anatomical differences (Eagly & others, 2004; Wood & Eagly, 2010). However, many psychologists (including many of those who write textbooks) are reluctant to point out the gender differences that have been substantiated. Why? Basically, because some people are quick to equate a gender difference with a gender deficiency. For example, women’s differences from men have historically been used to suggest that women are inferior to men (Moradi & others, 2010; Nutt, 2010). Not surprisingly, the gender-difference-equals-inferiority argument has also been used by some to suggest that men are inferior to women.

Beyond claims of inferiority, beliefs in gender differences have also been used to deny opportunities to one sex or the other. Here’s an example. In the early 1970s, many people—including educators and politicians—believed that girls lacked the strength, stamina, or aggressiveness needed to participate in competitive sports. Girls just weren’t suited to such activities, was the claim. In 1971, only 1 in 27 girls in the United States played high school sports. Today, almost 3 million girls—or 1 in every 2.5 girls—play on varsity high school sports teams in the United States (Women’s Sports Foundation, 2013). Why the leap in sports participation? A major factor was the passage of Title IX, a federal law that forbids sex discrimination in educational programs, including athletics, by any institution receiving federal funds.

We’ve already noted some gender differences in previous chapters, such as male–

Second, finding that a gender difference exists is one matter. Explaining what caused that difference is another matter altogether. For instance, consider the observation that women are more likely than men to wear earrings. This finding says nothing about the cause of that difference. Acknowledging that a gender difference exists does not automatically mean that such differences are “natural,” “inevitable,” or “unchangeable.” Nor does it necessarily mean that the differences are biologically based.

Bearing these qualifications in mind, let’s look at three areas of gender differences: personality, cognitive abilities, and sexual attitudes and behaviors. Although some differences do exist in these areas, men and women are more similar than they are different (Hyde, 2007, 2014).

MYTH !lhtriangle! SCIENCE

Is it true that most gender differences are caused by biological factors?

PERSONALITY DIFFERENCES

For most personality characteristics, there are no significant average differences between men and women. For example, women and men are, on average, very similar on such characteristics as impulsiveness and orderliness. However, men and women consistently differ on two personality dimensions. The first is that women tend to be more nurturant than men. The second is that men tend to be more assertive than women (Schmitt & others, 2008; Palomares, 2009).

Summarizing several studies, including cross-cultural research, psychologist Richard Lippa (2010) found that women tended to be more “people-oriented” and less “thing-oriented” than men. As psychologist Alice Eagly (1995a) observed, “In general, women tend to manifest behaviors that can be described as socially sensitive, friendly, and concerned with others’ welfare, whereas men tend to manifest behaviors that can be described as dominant, controlling, and independent.”

DIFFERENCES IN EMOTIONALITY

Many people also believe that women are much more emotional than men. One of our culture’s most pervasive gender stereotypes is that women express their emotions more frequently and intensely than men do. In contrast, men supposedly are calmer and possess greater emotional control (Vigil, 2009). Studies have shown that both men and women view women as the more emotional sex (Barrett & Bliss-Moreau, 2009). Women also place a higher value on emotional expressiveness than do men (Shields, 2002). But do such widely held stereotypes reflect actual gender differences in emotional experience?

Like so many stereotypes, the gender stereotypes of emotions are not completely accurate. As psychologists Michael Robinson and Gerald Clore (2002) point out, both men and women believe that their emotions differ far more than they actually do. In fact, research suggests that women and men are fairly similar in the experience of emotions, although they do differ in the expression of emotions. For example, researchers have found that women sometimes are more emotionally expressive than men, even when women and men do not differ in the self-ratings of emotions that they experience (Kring & Albert Gordon, 1998; Thunberg & Dimberg, 2000).

MYTH !lhtriangle! SCIENCE

Is it true that most women are more emotional than men?

How can we account for the gender differences in emotional expression? First, psychologists have consistently found differences in the types of emotions expressed by men and women (see Shields, 2002). Agneta Fischer and her colleagues (2004) reported a consistent pattern in 37 cultures around the world: Women report experiencing and expressing more sadness, fear, and guilt, while men report experiencing and expressing more anger and hostility. Fischer and her colleagues (2004) argue that the male role encourages the expression of emotions that emphasize power and assertiveness—emotions that confirm the person’s autonomy and status. In contrast, the female role encourages the expression of emotions that imply self-blame, vulnerability, and helplessness—emotions that help maintain social harmony with others by minimizing conflict and hostility.

For both men and women, the expression of emotions is also strongly influenced by culturally determined display rules, or societal norms of appropriate behavior in different situations. In many cultures, including the United States, women are allowed a wider range of emotional expressiveness and responsiveness than men. For men, it’s considered “unmasculine” to be too open in expressing certain emotions. Crying is especially taboo (Warner & Shields, 2007). Thus, there are strong cultural and gender-role expectations concerning emotional expressiveness and sensitivity.

Does women’s higher emotional expressivity clash with a high-powered career? You may have heard the stereotype that women’s tendency toward greater emotional expressiveness translates into an inability to be a strong leader. A recent Harvard Business Review (2013) headline, for example, read: “Emotional, bossy, too nice: The biases that still hold female leaders back.” Yet, there is research linking effective leadership with the ability to express emotions (Ilies & others, 2013; Riggio & Reicherd, 2008). And there are suggestions that successful leadership styles have shifted in recent years, with an increasing value placed on a combination of stereotypically masculine and stereotypically feminine traits (Koenig & others, 2011). These findings are good news for the slowly increasing numbers of women in top leadership positions that were historically held by men. From Marissa Mayer, President and CEO of Yahoo!, to Dilma Rousseff, President of Brazil, to Mary Barra, CEO of General Motors, it’s less surprising to see female leaders than it was even a decade ago.

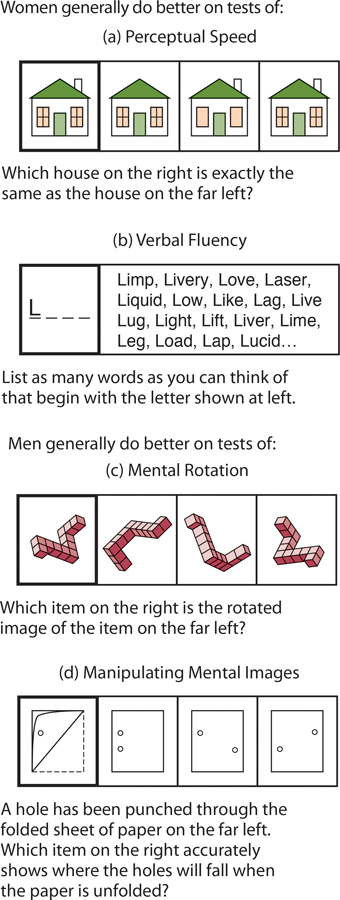

COGNITIVE DIFFERENCES

Is one sex smarter, more logical, or more creative than the other? No. For most cognitive abilities, there are no significant differences between males and females (Buss, 1995b; Hyde, 2007). However, once again, some limited differences do exist in this area (see FIGURE 10.2). Here are some of the best-substantiated gender-related cognitive differences.

Verbal, reading, and writing skills. Females consistently score much higher than males on tests of verbal fluency, reading comprehension, spelling, and, especially, basic writing skills (Lohman & Lakin, 2009). Although you rarely read about the “gender gap” in writing skills, females typically outperform males in this area.

Spatial skills. Males outscore females on some, but not all, tests of spatial skills (Stancey & Turner, 2010). For example, males consistently outperform females on tests measuring the ability to mentally rotate three-dimensional figures (Jansen & Heil, 2010). On the other hand, women are significantly better than men at remembering the location of objects (Spiers & others, 2008; Voyer & others, 2007).

Math skills. On average, males do slightly better than females on tests of advanced mathematical ability (see Halpern & others, 2011).

The difference in math skills deserves more comment. One widely believed stereotype is that males are much better than females at math (Schmader & others, 2004). However, over the last several decades, the so-called gender gap in mathematics has been steadily narrowing. Today, girls score just as highly as boys on national tests of math skills (Else-Quest & others, 2010). However, it is true that more males than females score in the very highest range in advanced math achievement tests (Lohman & Lakin, 2009; McGraw & others, 2006; Forgasz & others, 2010). One possible explanation is that very advanced mathematics draws heavily upon spatial abilities (Halpern & others, 2007).

Even when differences exist, they may be culturally influenced. For example, a study focused on science performance found that although there is a gap in favor of boys in the United States, that is not the case worldwide. An international study of 65 countries found no overall differences (OECD, 2010). In fact, in 21 countries, girls performed better, on average, than boys, while in 11 countries, boys performed better, on average, than girls. There was no significant difference in the remaining countries.

MYTH !rhtriangle! SCIENCE

Is it true that girls score just as highly as boys on national tests of math skills?

Some researchers believe that cognitive differences between the sexes, such as the female advantage in verbal skills and the male advantage in spatial skills, are due to sex differences in brain function or organization. However, as we discussed in Chapter 2, male and female brains are, like male and female personality traits, far more similar than different (Halpern & others, 2011; Jordan-Young, 2010).

Further, there is evidence that it may be the expression of gender roles, rather than gender itself, that leads to this gender difference. A meta-analysis of studies from five countries found that higher levels of masculinity, for both women and men, predicted better mental rotation. Meanwhile, there was no significant correlation between femininity and mental rotation (Reilly & Neumann, 2013). We explore gender differences in science and mathematics further in the Critical Thinking box.

CRITICAL THINKING

Gender Differences: Women in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Fields

In recent years, the research on gender differences in cognitive abilities, particularly those related to math, has focused on the disproportionately low numbers of women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. At each level of education and career, there are fewer and fewer women (Goulden & others, 2011). For example, women have earned more than 30% of social and behavioral science doctorates in the United States for more than 30 years, but only make up about 15% of current full professors at top research institutions. The imbalance is even more extreme in other STEM fields (National Academy of Sciences [NAS], 2007).

A number of psychology researchers have examined the reasons for this gender imbalance. As we learned in the chapter, research exploring possible gender differences in cognitive abilities has largely dismissed this as a primary influence (Hyde, 2014). For example, we learned earlier that an international study of science performance found no overall difference, with girls performing better than boys in 21 countries, boys performing better than girls in 11 countries, and no significant difference in 33 countries (OECD, 2010).

Many researchers have explored the impacts of discrimination and implicit bias that may directly or indirectly drive women’s choices and opportunities (Raymond, 2013). For example, Corinne Moss-Racusin and her colleagues (2012) had science professors rate job applications for a lab position. The applications were identical except for the name—Jennifer versus John. Both male and female professors gave higher average ratings to John than Jennifer, and suggested a starting salary for John that was several thousand dollars higher than what they recommended for Jennifer. They also indicated that they would offer John more career mentoring, on average, than they would offer Jennifer.

In another study, more than 500,000 people from 34 countries completed an Implicit Association Test (IAT), a test that measures unconscious associations. (You can try an IAT on gender stereotypes in the Think Like a Scientist feature.) More than 70% of participants in this study unconsciously viewed science as more of a masculine than a feminine pursuit (Nosek & others, 2009).

There is some evidence that biased tendencies can be altered. For example, researchers exposed some college students to news articles that were either about social change or traditional gender roles (Diekman & others, 2013). Those who read about social change were more likely to then choose to learn more about nontraditional gender roles. Other researchers have examined stereotype threat, a process that we explored in Chapter 7, Thinking, Language, and Intelligence. Stereotype threat occurs when members of a group fear that they will be evaluated based on a negative stereotype about that group. The anxiety that follows can lead to lower performance. With respect to STEM, researchers have found that girls and women perform more poorly when they think about their gender. However, women and girls perform at higher levels when given information that there is no gender difference on a task (Shapiro & Williams, 2012).

On the other hand, there is some evidence that women are choosing not to pursue STEM careers. Some blame the lack of female mentors and role models for this choice (Rosser, 2012). Others cite the effects of deeply rooted gender norms. For example, Lisa DiDonato and JoNell Strough (2013) found that college students tended to prefer gender stereotypical majors and careers for themselves. In addition, Amanda Diekman and her colleagues found that students who viewed themselves as more “communal”—that is, oriented toward other people and interested in maintaining interpersonal relationships—were less likely to be interested in STEM careers. Female students were more likely to view themselves as communal than male students (Diekman & others, 2010).

Researchers and policy makers have identified a number of solutions to the problem of gender imbalance in STEM fields. First, formal recruitment and retention practices should be established to increase the numbers of women (NAS, 2007). Second, researchers and policy groups have questioned the inherently rigid structure of many STEM careers—for example, the large amount of time spent on campus to conduct laboratory experiments. The National Academy of Sciences (2007) pointed out that “anyone lacking the work and family support traditionally provided by a ‘wife’ is at a serious disadvantage.” But, the NAS observed, men were more likely than women to have a spouse at home to provide family support. Other researchers found that the gender gap in STEM achievement was greater between women and men with children than between women and men without children (Goulden & others, 2009). These researchers encouraged structural changes in STEM fields, like flexible hours and child care, that would benefit both women and men. Psychological science is helping both to explain gender disparities in STEM and to identify solutions.

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

Have you or your friends ever felt pressure to like or to dislike a certain academic discipline based on your gender? Have you ever felt pressure to perform well in a task that is not stereotypically associated with your gender?

What institutional structures and policy changes might make a career in STEM more hospitable to both women and men who want families?

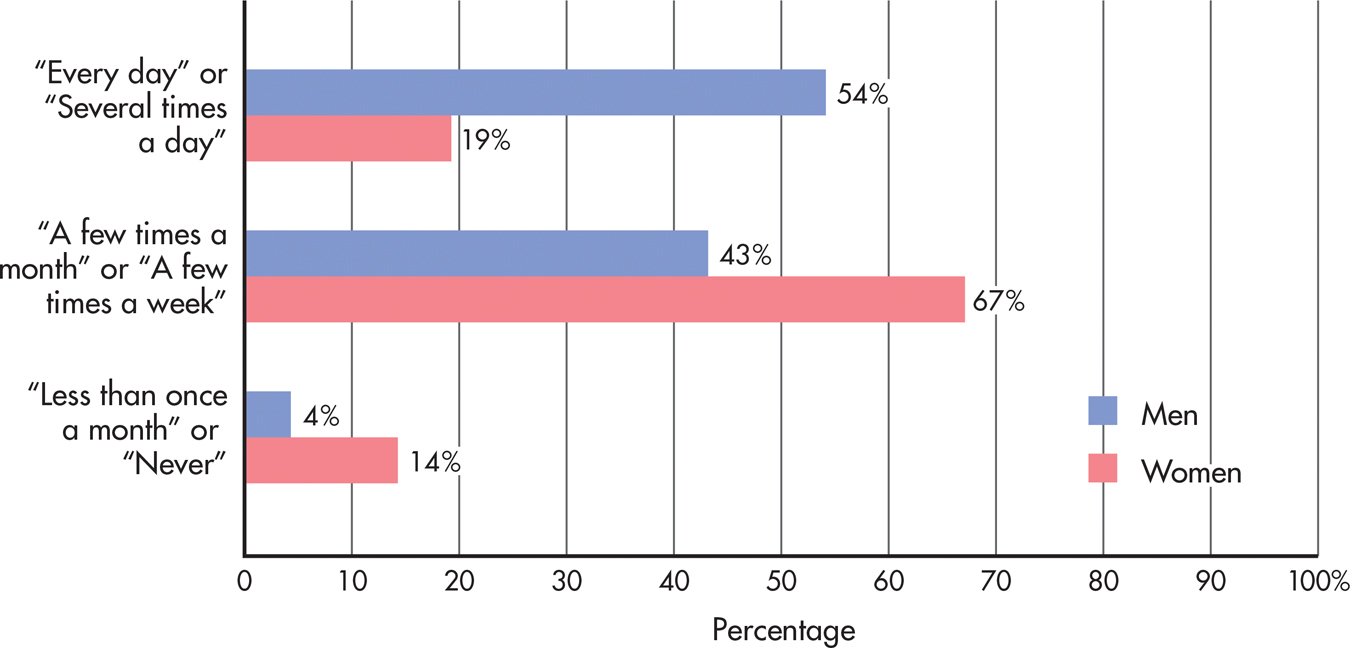

SEXUAL ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIORS

Do men and women differ in their sexual attitudes, preferences, and behaviors? A recent meta-analysis of over 800 studies from 87 different countries investigated gender differences in sexuality (Petersen & Hyde, 2010). The meta-analysis found that men and women were similar on many dimensions. There were only small differences between men and women. However, men reported more permissive sexual attitudes than women, including much greater acceptance of casual sex. Men also tended to have more sexual partners than women and experienced their first intercourse at an earlier average age. The biggest difference was in the incidence of masturbation and use of pornography, with men reporting a higher incidence than women (Petersen & Hyde, 2010).

However, these results must be taken with a grain of salt. Some researchers have found that both men and women tend to be less than honest in their responses to questions about their sexual behaviors and attitudes (Alexander & Fisher, 2003). Both sexes distort their responses to better match gender norms and expectations—although in opposite directions (Fisher, 2009). While women tend to downplay or minimize their sexual experiences, men tend to exaggerate theirs. In addition, some surveys have found fewer or no sex differences in terms of numbers of sexual partners, desired number of sexual partners, and actual sexual behavior, especially among college students (Paul & others, 2000; Pedersen & others, 2002).

So there you have it. On the whole, men and women are more similar than they are different. In the next section, we’ll look at how each of us learns to identify ourselves as either male or female.