10.5 Sexual Behavior

KEY THEME

Intimate, committed relationships are typically established during early adulthood, but they remain important throughout the lifespan.

KEY QUESTIONS

What characterizes the sexual behavior patterns of adulthood?

What are some important aspects of sexual relationships in late adulthood?

Films, television shows, magazines and Internet sites tend to offer overheated images of sexual activity. If you believe the not-so-subtle media messages, everyone (except you) has such an active, steamy, and varied sex life that you can’t help wondering how anyone (except you) ever finds the time to get their laundry done.

So, to prevent unnecessary despondency, let’s deal with the “everybody’s-sex-life-is-better-than-mine” issue at the beginning of this section. Are the media images accurate?

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

Romantic Love and the Brain

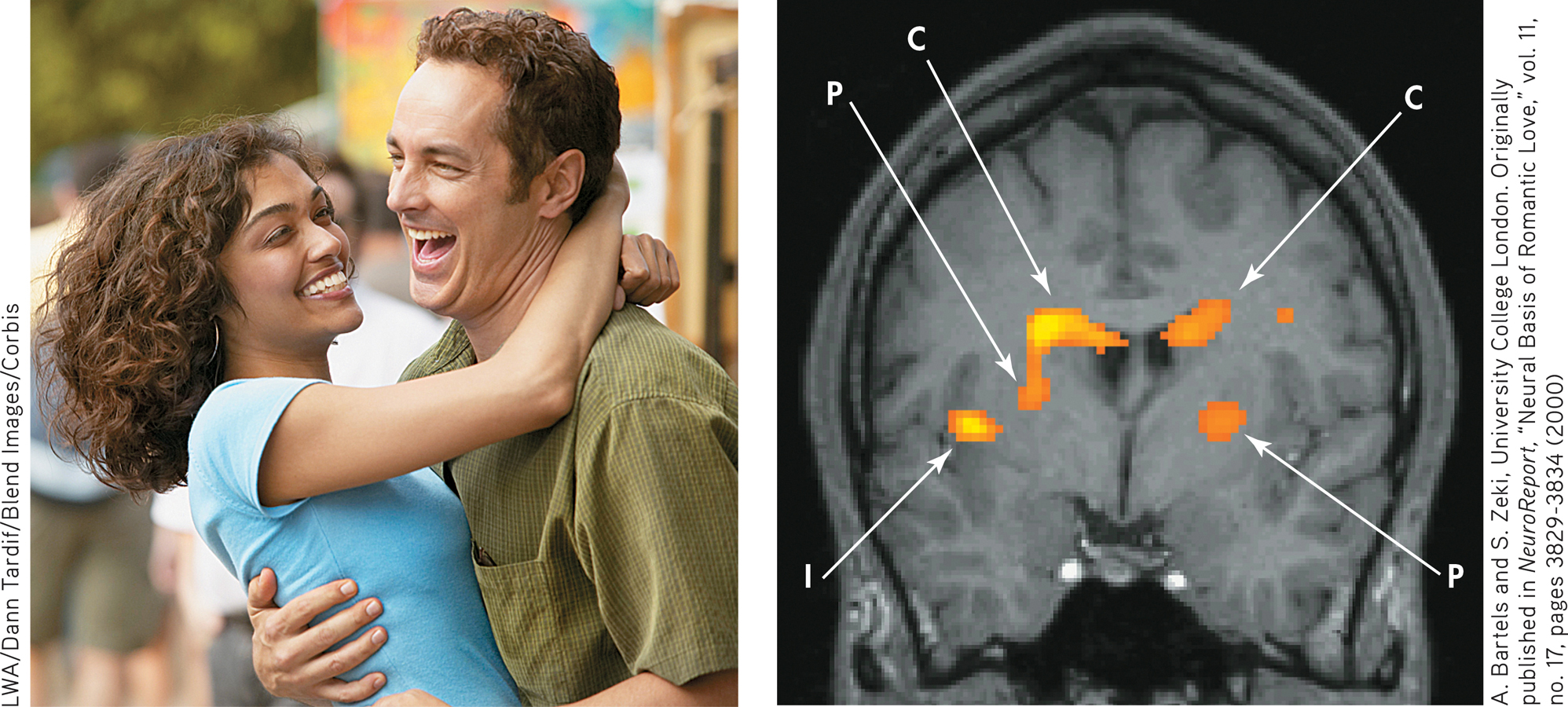

When it comes to love, it’s been said that the brain is the most erotic organ in your body. Indeed, being head over heels in love is an emotionally intoxicating brain state. Do the overpowering feelings of romantic love involve a unique pattern of brain activity?

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to detect brain activity, researchers Andreas Bartels and Semir Zeki (2000) investigated that idea with 17 love-struck young adults, all professing to be “truly, deeply, madly in love” with their romantic partner. Each participant was scanned several times while gazing at a photo of the romantic partner. Alternating with the “love” scans were “friendship” scans taken while the participant looked at a photo of a good friend who was of the same sex as the loved one.

Bartels and Zeki’s (2000) results suggest that romantic love activates brain areas that are involved in other positive emotions, such as happiness, but in a way that represents a unique pattern. Shown here is an fMRI brain scan depicting some of the brain areas activated by romantic love. Compared to looking at a photo of a close friend, looking at a photo of one’s romantic partner produced heightened activity in four brain areas associated with emotion, including the anterior cingulate cortex (not shown), caudate nucleus (C), putamen (P), and insula (I).

Given the complexity of the sentiment of romantic love, the researchers were surprised that the brain areas activated were so small and limited to so few regions. Nonetheless, the four activated brain areas offer some insight into the intoxicating effects of romantic love. Why? Because these are the same brain areas that are activated in response to euphoria-producing drugs, such as opiates and cocaine. And the good news is that these brain areas remain activated long beyond the early excitement of new love. A study of long-term couples—married an average of about 21 years—showed a similar pattern (Acevedo & others, 2011).

A. Bartels and S. Zeki, University College London. Originally published in NeuroReport, “Neural Basis of Romantic Love,” vol. 11, no. 17, pages 3829-3834 (2000)

Interestingly, the flip side is true as well. Romantic love activates the same regions as the biological euphoria from certain drugs, and romantic breakups activate the same regions as physical pain. In an article titled “Broken Hearts and Broken Bones,” Naomi Eisenberger (2012) outlined the biological similarities between social and physical pain. Both types of pain include increased activity in the anterior cingulate cortex and insula. Researchers even found that acetaminophen, often sold as Tylenol, reduced the emotional pain of social rejection as compared to a placebo (DeWall & others, 2010). Hurt feelings, then, may be more than a metaphor. Clearly, there seem to be some close neural links between romantic love and euphoric states.

IN FOCUS

Everything You Wanted to Know About Sexual Fantasies

The brain is the most erotic organ in the human body. After all, the brain plays a pivotal role in the expression of human sexuality. What people think about and imagine influences how they behave sexually. And, in turn, people’s sexual behavior can influence the content of their sexual fantasies—erotic or sexually arousing mental images. In the realm of human sexuality, the mind–

We experience sexual fantasies in the private theater of our own minds, but psychologists have discovered that sexual fantasies are a nearly universal human phenomenon. Using checklists and questionnaires, researchers have been able to answer various questions about people’s sexual fantasies. With the help of excellent research summaries by University of North Texas psychologists Joseph W. Critelli and Jenny M. Bivona (2008) and University of Vermont psychologists Harold Leitenberg and Kris Henning (1995), we’ll answer some questions about this private human experience.

When and How Often Do People Have Sexual Fantasies?

Sexual fantasies tend to begin during the adolescent years, and almost all adult men and women (95 percent) report having had sexual daydreams. It is very common for both men and women occasionally to engage in sexual fantasies during intercourse. But compared to women, men report a higher incidence of sexual fantasies during masturbation and nonsexual activities. In short, men tend to think about sex more often than do women.

What Do People Have Sexual Fantasies About?

If you accept the notion that any fantasy, sexual or not, is based to some degree on life experiences, the three most common types of sexual fantasies that men and women have won’t surprise you. They are (1) reliving an exciting sexual experience, (2) imagining that they are having sex with their current partner, and (3) imagining that they are having sex with a different partner.

Do Male and Female Sexual Fantasies Differ?

There are some well-substantiated differences. First, men tend to fantasize themselves in active roles—that is, doing something sexual to their partner. In contrast, women tend to imagine themselves in sexually passive roles—that is, having something sexual done to them.

Second, men tend to have sexual fantasies with more explicit imagery, often involving specific sexual positions or anatomical details. Women are more likely to imagine romantic themes, including warm, loving feelings about their partner and details about the romantic ambiance of the scene.

Third, men are more likely to imagine having sex with short-term partners or with multiple partners (Buss & Schmitt, 2011; King & others, 2009). As Leitenberg and Henning (1995) put it, “Fantasizing about having sex with multiple partners at the same time appears to be more consonant with the male stereotype of being a ‘superstud’ than with the female stereotype of wanting a close, loving, monogamous relationship.”

Are Sexual Fantasies Psychologically Unhealthy?

Some people are troubled by their sexual fantasies. About 25 percent of people experience some degree of guilt over having sexual fantasies. This guilt is usually due to the belief that their sexual fantasies are immoral, are harmful to their relationships, or indicate that something is wrong with them.

However, the people who engage in sexual fantasies most often tend to exhibit the least number of sexual problems and the lowest level of sexual dissatisfaction (Leitenberg & Heming, 1995). The bottom line: Sexual fantasies seem to be a common, normal element of human sexuality.

In this section, we’ll use descriptive research to explore the “Who’s doing what, when, how often, and with whom” questions about human sexuality. To give you an accurate picture, we’ll rely on data from three scientifically conducted national surveys. The National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB) focused on the sexual practices of Americans between the ages of 14 and 94 (Reece & others, 2010a). The National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) targeted a younger group, studying the sexual behavior of males and females between the ages of 15 and 44 (Mosher & others, 2005). And, the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) studied sexual practices and attitudes in older Americans ages 57–

How Many Sexual Partners Do People Have?

Males tend to desire and have more sexual partners than females (King & others, 2009; Petersen & Hyde, 2010). More than half (53%) of men but only about a third (31%) of women in the 25 to 44 age group reported having had seven or more sexual partners to date (Mosher & others, 2005). Now consider a shorter time frame and take your best guess. How many sexual partners did most adults in the same age group have in the past year? Over 70% of males and females had either one or no sexual partner in the previous year (Mosher & others, 2005).

MYTH !lhtriangle! SCIENCE

Is it true that most adults have had multiple sexual partners in the last year?

Clearly, such scientific findings contradict many of the steamy, hypersexualized media portrayals of adult sexuality. Fictional portrayals aside, the obvious question is why most people in this age group report having just one sexual partner in the past year. The short answer is commitment and marriage. The onset of adulthood marks a commitment to the task of establishing long-term, intimate relationships. During their twenties, most men and women develop an intimate relationship with another adult. By the age of 30, most Americans are part of a couple—either married or cohabiting with someone (Goodwin & others, 2009; Mosher & others, 2005).

IN FOCUS

Hooking Up on Campus

Pop culture and the news media alike have been abuzz about today’s hook-up culture. Katy Perry sings, “There’s a stranger in my bed, there’s a pounding in my head,” in her number one Billboard hit, “Last Friday Night (T.G.I.F.)” (Perry & others, 2011). And reporter Kate Taylor (2013) of The New York Times wrote a long piece about the “hook-up” culture on U.S. university campuses. “It is by now pretty well understood,” Taylor wrote, “that traditional dating in college has mostly gone the way of the landline” (2013).

Although there’s nothing new about casual sex among young adults, hooking up does differ in some key ways from casual sex. Casual sex refers, by definition, to sexual intercourse, with or without an emotional or friendly relationship. In a “friends with benefits” relationship, the sexual relationship is presumed to be secondary to the friendship. In contrast, “hooking up” refers to a no-strings-attached, sexual encounter that can range from kissing and cuddling to sexual intercourse. The actual sexual behaviors may vary, but the common thread is that the sexual intimacy is not accompanied by the expectation of a committed relationship or even future interactions (Owen & others, 2010; Reiber & Garcia, 2010). Indeed, one college junior told Taylor about her regular hook-up: “We don’t really like each other in person, sober,” and observed that “we literally can’t sit down and have coffee” (Taylor, 2013).

On many college campuses, hooking up is very common. Studies have shown that about 80% of students reported hooking up at least once while they were in college, and more than half had hooked up during the previous year (Owen & others, 2010; Reiber & Garcia, 2010). In one study, about 60% of students reported that their most recent hook-up partner was a new partner, and of those who had oral, anal, or vaginal sex, less than half said that they used a condom (Lewis & others, 2012). College men generally hold more permissive attitudes toward casual sex than women, and hooking up is no exception (Petersen & Hyde, 2010). Perhaps not surprisingly, alcohol use is strongly implicated in hooking up behavior. Alcohol precedes almost two-thirds of hook-ups (Fielder & Carey, 2010; Vander Ven & Beck, 2009).

Male college students have more favorable attitudes toward hooking up than female college students, although the sexes may not be as far apart as some people think (Bradshaw & others, 2010). As compared to men, women tend to report more negative emotional reactions after hooking up than men (Lewis & others, 2012). However, both men and women reported that hooking up had overall been a more positive than negative experience (Lewis & others, 2012; Owen & Fincham, 2010).

Although hooking up is widely accepted on college campuses, both sexes overestimate the degree to which the opposite sex is comfortable with hooking up (Reiber & Garcia, 2010). Today’s young adults haven’t given up on the hope of creating a long-term committed relationship. Indeed, one college senior quoted in Taylor’s news article described how a romantic relationship she had during a study-abroad experience made her hopeful that she would one day have such a relationship back home (Taylor, 2013). However, college students appear to have embraced what appears to be a larger cultural shift toward more flexible, less clearly defined relationships (Bisson & Levine, 2009).

Marriage continues to be a cornerstone of American society as well as a major developmental milestone for most people on the trek through adulthood. Even so, the timing of marriage has changed over the past couple of generations. In 1960, the average age of first marriage for men was 23 versus 20 for women. Today, the average age of first marriage is about 28 for men and 26 for women (Daniels & others, 2012; Goodwin & others, 2009). Most young adults experience considerable social pressure to “settle down,” find a partner, and marry. Doing so confers numerous benefits, not the least of which is the social, legal, and moral acceptance of the sexual partnership.

How Often Do People Engage in Sexual Activity?

Perhaps the widest disparity between the media images and scientific results involves the issue of how often people have sex. Here’s what the NSSHB found: About 35% of men and 40% of women ages 18–

In general, most people between the ages of 18 and 59 have engaged in traditional sexual behaviors in the past year. Vaginal intercourse is quite common for both men (80%) and women (86%). About 37% of both men and women give oral sex to their partner and about 44% of men and 31% of women have received it. A very small minority of men and women (about 3–

Which Americans have the most active sex lives? Although you might guess young, single adults, the fact is that married or cohabiting couples have the most active sex lives (Herbenick & others, 2010b; Reece & others, 2010b). If you think about it, this finding makes sense. Sexual activity is strongly regulated by the availability of a sex partner. Being a member of a stable couple is the social arrangement most likely to produce a readily accessible sexual partner.

Do people enjoy their sex lives? According to the NSSHB, about 85% of men, as compared to two-thirds of women, reported that their most recent sexual experience was pleasurable. Interestingly, men tended to overestimate their partner’s enjoyment. About 85% of men thought that their partner had experienced an orgasm in their last sexual encounter, but only about 64% of women agreed (Herbenick & others, 2010a, 2010b). For both women and men, diversity of sexual repertoires was associated with a greater likelihood of achieving orgasm (Herbenick & others, 2010a, 2010b).

Sex After Sixty? Seventy?! Eighty?!!

The myth? Sexual interest and potency evaporate on the day you become eligible for Medicare. The reality? More than half of people aged 60 to 85 years old are sexually active. In fact, about one-third of 75to 85-year-olds remain sexually active (Lindau & Gavrilova, 2010).

Age, by itself, is not the most critical factor influencing senior sexuality. Physical health and having an intimate partner exert a stronger influence on the likelihood and frequency of sexual activity among senior adults (Lindau & Gavrilova, 2010). But when serious physical health issues are not an issue, two-thirds (65%) of those in the 65-to-74 age range who had an intimate partner had sex more than 2 or 3 times per month. Among the 75-to-85 crowd with an intimate companion, more than half (54%) had sex more than 2 or 3 times per month (Lindau & others, 2007; Waite & others, 2009).

MYTH !lhtriangle! SCIENCE

Is it true that once they are in their 70s and 80s, almost no adults are sexually active?

Aging can have some effects on the friskiness of seniors. About half of all sexually active senior adults report at least one bothersome sexual problem (Lindau & Gavrilova, 2010). As men and women age, it takes longer to become sexually aroused and achieve orgasm (Waite & others, 2009). For women, vaginal lubrication typically occurs more slowly, sometimes necessitating the use of lubricants during intercourse. With increasing age, men are more likely to experience difficulties achieving or maintaining erection (Gades & others, 2009). But despite the inevitable physical changes that accompany aging, it is clear that love and affection can continue to thrive—and grow—in the twilight years of life.

Many people who have lost their spouse through death or divorce continue to date as they grow older. Older men date more often than older women, mostly because they have a larger pool of potential dating partners. Dating serves a different function in late adulthood than in early adulthood. For young adults, dating is part of the process of selecting a mate. For older adults, dating fills the need for companionship and sexual intimacy. Many older adults have a serious relationship with a single, special dating partner, or may even live with their partner but have no intention of remarrying (King & Scott, 2005; Waite & others, 2009). In late adulthood, dating helps prevent loneliness and can meet the need for physical and emotional intimacy that continues throughout the lifespan.

Test your understanding of Human Sexuality and Sexual Behavior with

.

.