11.2 The Psychoanalytic Perspective on Personality

KEY THEME

Freud’s psychoanalysis stresses the importance of unconscious forces, sexual and aggressive instincts, and early childhood experience.

KEY QUESTIONS

What were the key influences on Sigmund Freud’s thinking?

How are unconscious influences revealed?

What are the three basic structures of personality, and what are the defense mechanisms?

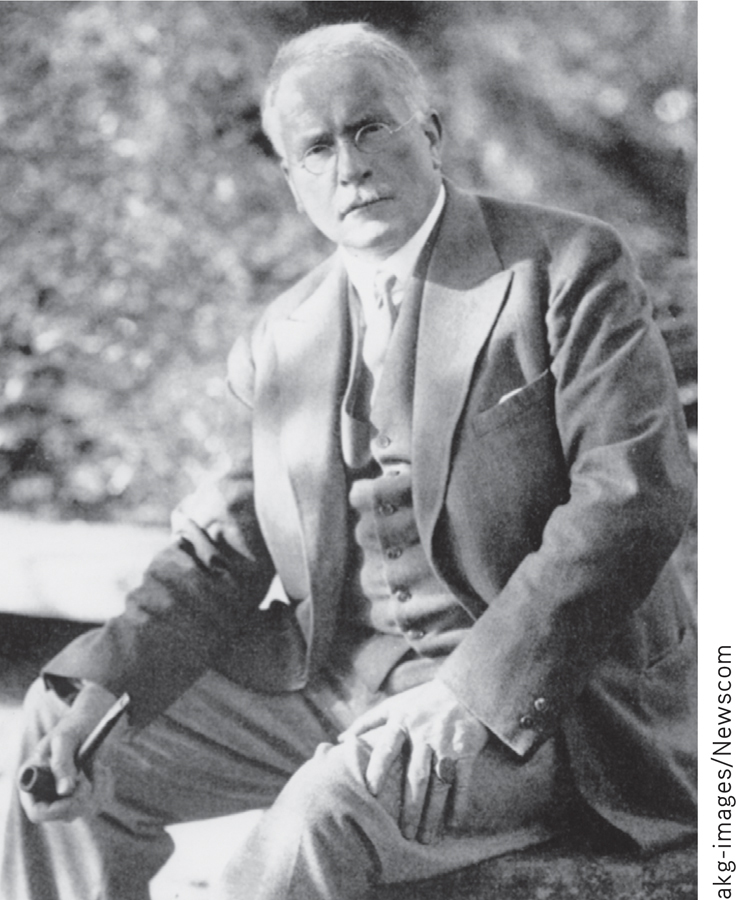

Sigmund Freud, one of the most influential figures of the twentieth century, was the founder of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis is a theory of personality that stresses the influence of unconscious mental processes, the importance of sexual and aggressive instincts, and the enduring effects of early childhood experience on personality. Because so many of Freud’s ideas have become part of our common culture, it is difficult to imagine just how radical he seemed to his contemporaries. The following biographical sketch highlights some of the important influences that shaped Freud’s ideas and theory.

psychoanalysis (in personality)

Sigmund Freud’s theory of personality, which emphasizes unconscious determinants of behavior, sexual and aggressive instinctual drives, and the enduring effects of early childhood experiences on later personality development.

The Life of Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud was born in 1856 in what is today Pribor, Czech Republic. When he was 4 years old, his family moved to Vienna, where he lived until the last year of his life. Sigmund was the firstborn child of Jacob and Amalie Freud. By the time he was 10 years old, there were six more siblings in the household. Of the seven children, Sigmund was his mother’s favorite. As Freud later wrote, “A man who has been the indisputable favorite of his mother keeps for life the feeling of being a conqueror, that confidence of success that often induces real success” (Jones, 1953).

Freud was extremely intelligent and intensely ambitious. He studied medicine, became a physician, and then proved himself to be an outstanding physiological researcher. Early in his career, Freud was among the first investigators of a new drug that had anesthetic and mood-altering properties—cocaine. However, one of Freud’s colleagues received credit for the discovery of the anesthetic properties of cocaine, which left Freud bitter. Adding to his disappointment, Freud’s enthusiasm for the medical potential of cocaine quickly faded when he recognized that the drug was addictive (Fancher, 1973; Gay, 2006).

Prospects for an academic career in scientific research were very poor, especially for a Jew in Vienna, which was intensely anti-Semitic at that time. So when he married Martha Bernays in 1886, Freud reluctantly gave up physiological research for a private practice in neurology. The income from private practice would be needed: Sigmund and Martha had six children. One of Freud’s daughters, Anna Freud, later became an important psychoanalytic theorist.

INFLUENCES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF FREUD’S IDEAS

Freud’s theory evolved gradually during his first 20 years of private practice. He based his theory on observations of his patients as well as on self-analysis. An early influence on Freud was Joseph Breuer, a highly respected physician. Breuer described to Freud the striking case of a young woman with an array of puzzling psychological and physical symptoms. Breuer found that if he first hypnotized this patient, then asked her to talk freely about a given symptom, forgotten memories of traumatic events emerged. After she freely expressed the pent-up emotions associated with the event, her symptom disappeared. Breuer called this phenomenon catharsis (Freud, 1925).

At first, Freud embraced Breuer’s technique, but he found that not all of his patients could be hypnotized. Eventually, Freud dropped the use of hypnosis and developed his own technique of free association to help his patients uncover forgotten memories. Freud’s patients would spontaneously report their uncensored thoughts, mental images, and feelings as they came to mind. From these “free associations,” the thread that led to the crucial long-forgotten memories could be unraveled. Breuer and Freud described several of their case studies in their landmark book, Studies on Hysteria. Its publication in 1895 marked the beginning of psychoanalysis.

free association

A psychoanalytic technique in which the patient spontaneously reports all thoughts, feelings, and mental images that arise, revealing unconscious thoughts and emotions.

In 1900, Freud published what many consider his most important work, The Interpretation of Dreams. By the early 1900s, Freud had developed the basic tenets of his psychoanalytic theory and was no longer the isolated scientist. He was gaining international recognition and developing a following.

In 1904, Freud published what was to become one of his most popular books, The Psychopathology of Everyday Life. He described how unconscious thoughts, feelings, and wishes are often reflected in acts of forgetting, inadvertent slips of the tongue, accidents, and errors. By 1909, Freud’s influence was also felt in the United States, when he and other psychoanalysts were invited to lecture at Clark University in Massachusetts. For the next 30 years, Freud continued to refine his theory, publishing many books, articles, and lectures.

The last two decades of Freud’s life were filled with many personal tragedies. The terrible devastation of World War I weighed heavily on his mind. In 1920, one of his daughters died. In the early 1920s, Freud developed cancer of the jaw, a condition for which he would ultimately undergo more than 30 operations. And during the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Nazis were steadily gaining power in Germany.

Given the climate of the times, it’s not surprising that Freud came to focus on humanity’s destructive tendencies. For years he had asserted that sexuality was the fundamental human motive, but now he added aggression as a second powerful human instinct. During this period, Freud wrote Civilization and Its Discontents (1930), in which he applied his psychoanalytic perspective to civilization as a whole. The central theme of the book is that human nature and civilization are in basic conflict—a conflict that cannot be resolved.

Freud’s extreme pessimism was undoubtedly a reflection of the destruction he saw all around him. By 1933, Adolf Hitler had seized power in Germany. Freud’s books were banned and publicly burned in Berlin. Five years later, the Nazis marched into Austria, seizing control of Freud’s homeland. Although Freud’s life was clearly threatened, it was only after his youngest daughter, Anna, had been detained and questioned by the Gestapo that Freud reluctantly agreed to leave Vienna. Under great duress, Freud moved his family to the safety of England. A year later, his cancer returned. In 1939, Freud died in London at the age of 83 (Gay, 2006).

This brief sketch cannot do justice to the richness of Freud’s life and the influence of his culture on his ideas. Today, Freud’s legacy continues to influence psychology, philosophy, literature, art, and psychotherapy (Merlino & others, 2008; O’Roark, 2007).

Freud’s Dynamic Theory of Personality

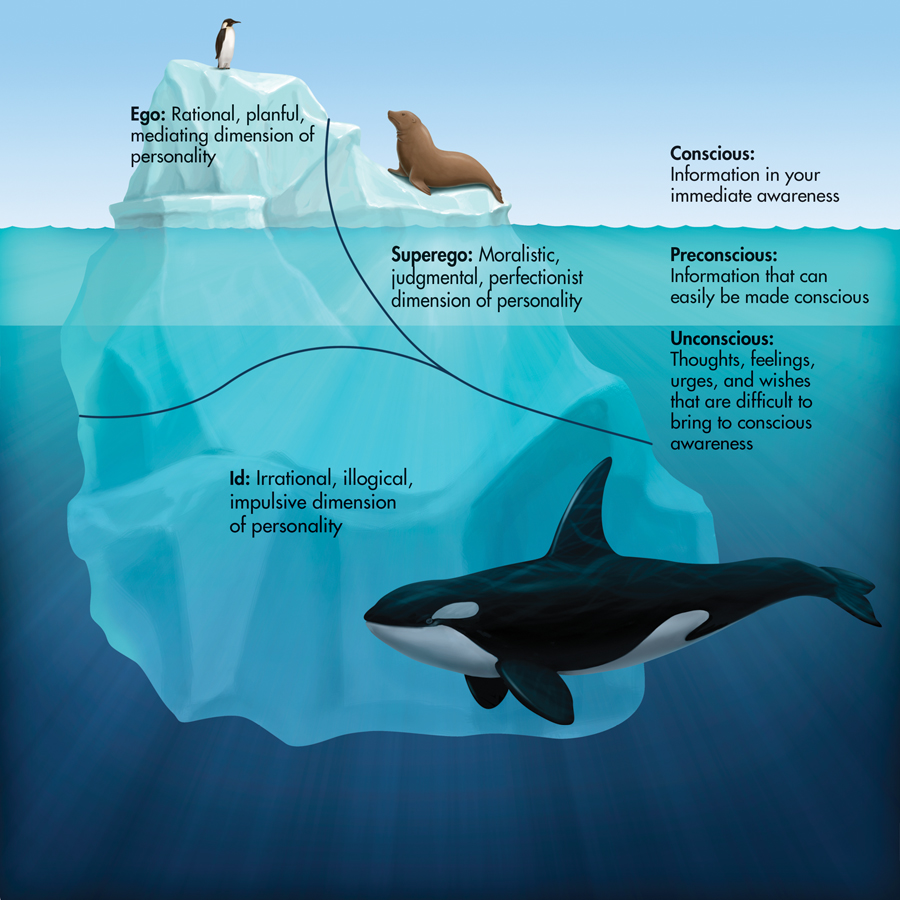

Freud (1940) saw personality and behavior as the result of a constant interplay among conflicting psychological forces. These psychological forces operate at three different levels of awareness: the conscious, the preconscious, and the unconscious. All the thoughts, feelings, and sensations that you’re aware of at this particular moment represent the conscious level. The preconscious contains information that you’re not currently aware of but can easily bring to conscious awareness, such as memories of recent events or your street address.

However, the conscious and preconscious are merely the visible tip of the iceberg of the mind. The bulk of this psychological iceberg is made up of the unconscious, which lies submerged below the waterline of the preconscious and conscious (see FIGURE 11.1 below). You’re not directly aware of these submerged thoughts, feelings, wishes, and drives, but the unconscious exerts an enormous influence on your conscious thoughts and behavior.

unconscious

In Freud’s theory, a term used to describe thoughts, feelings, wishes, and drives that are operating below the level of conscious awareness.

Although it is not directly accessible, Freud (1904) believed that unconscious material often seeps through to the conscious level in distorted, disguised, or symbolic forms. Like a detective searching for clues, Freud carefully analyzed his patients’ reports of dreams and free associations for evidence of unconscious wishes, fantasies, and conflicts. Dream analysis was particularly important to Freud. “The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind,” he wrote in The Interpretation of Dreams (1900). Beneath the surface images, or manifest content, of a dream lies its latent content—the true, hidden, unconscious meaning that is disguised in the dream symbols (see Chapter 4).

Freud (1904, 1933) believed that the unconscious can also be revealed in unintentional actions, such as accidents, mistakes, instances of forgetting, and inadvertent slips of the tongue, which are often referred to as “Freudian slips.” According to Freud, many seemingly accidental or unintentional actions are not accidental at all, but are determined by unconscious motives.

THE STRUCTURE OF PERSONALITY

According to Freud (1933), each person possesses a certain amount of psychological energy. This psychological energy develops into the three basic structures of personality—the id, the ego, and the superego (see FIGURE 11.1). Understand that these are not separate identities or brain structures. Rather, they are distinct psychological processes.

The id, the most primitive part of the personality, is entirely unconscious and present at birth. The id is completely immune to logic, values, morality, danger, and the demands of the external world. It is the original source of psychological energy, parts of which will later evolve into the ego and superego (Freud, 1933, 1940). The id is rather difficult to describe in words. “We come nearer to the id with images,” Freud (1933) wrote, “and call it a chaos, a cauldron of seething excitement.”

The id’s reservoir of psychological energy is derived from two conflicting instinctual drives: the life instinct and the death instinct. The life instinct, which Freud called Eros, consists of biological urges that perpetuate the existence of the individual and the species—hunger, thirst, physical comfort, and, most important, sexuality. Freud (1915c) used the word libido to refer specifically to sexual energy or motivation. The death instinct, which Freud (1940) called Thanatos, is destructive energy that is reflected in aggressive, reckless, and life-threatening behaviors, including self-destructive actions.

id

Latin for the it; in Freud’s theory, the completely unconscious, irrational component of personality that seeks immediate satisfaction of instinctual urges and drives; ruled by the pleasure principle.

Eros

The self-preservation or life instinct, reflected in the expression of basic biological urges that perpetuate the existence of the individual and the species.

libido

The psychological and emotional energy associated with expressions of sexuality; the sex drive.

Thanatos

The death instinct, reflected in aggressive, destructive, and self-destructive actions.

The id is ruled by the pleasure principle—the relentless drive toward immediate satisfaction of the instinctual urges, especially sexual urges (Freud, 1920). Thus, the id strives to increase pleasure, reduce tension, and avoid pain. Even though it operates unconsciously, Freud saw the pleasure principle as the most fundamental human motive.

pleasure principle

The motive to obtain pleasure and avoid tension or discomfort; the most fundamental human motive and the guiding principle of the id.

Equipped only with the id, the newborn infant is completely driven by the pleasure principle. When cold, wet, hungry, or uncomfortable, the newborn wants his needs addressed immediately. As the infant gains experience with the external world, however, he learns that his caretakers can’t or won’t always immediately satisfy those needs.

Thus, a new dimension of personality develops from part of the id’s psychological energy—the ego. Partly conscious, the ego represents the organized, rational, and planning dimensions of personality (Freud, 1933). As the mediator between the id’s instinctual demands and the restrictions of the outer world, the ego operates on the reality principle. The reality principle is the capacity to postpone gratification until the appropriate time or circumstances exist in the external world (Freud, 1940).

ego

Latin for I; in Freud’s theory, the partly conscious rational component of personality that regulates thoughts and behavior, and is most in touch with the demands of the external world.

reality principle

The capacity to accommodate external demands by postponing gratification until the appropriate time or circumstances exist.

As the young child gains experience, she gradually learns acceptable ways to satisfy her desires and instincts, such as waiting her turn rather than pushing another child off a playground swing. Hence, the ego is the pragmatic part of the personality that learns various compromises to reduce the tension of the id’s instinctual urges. If the ego can’t identify an acceptable compromise to satisfy an instinctual urge, such as a sexual urge, it can repress the impulse, or remove it from conscious awareness (Freud, 1915a).

In early childhood, the ego must deal with external parental demands and limitations. Implicit in those demands are the parents’ values and morals, their ideas of the right and wrong ways to think, act, and feel. Eventually, the child encounters other advocates of society’s values, such as teachers and religious and legal authorities (Freud, 1926). Gradually, these social values move from being externally imposed demands to being internalized rules and values.

By about age 5 or 6, the young child has developed an internal, parental voice that is partly conscious—the superego. As the internal representation of parental and societal values, the superego evaluates the acceptability of behavior and thoughts, then praises or admonishes. Put simply, your superego represents your conscience, issuing demands “like a strict father with a child” (Freud, 1926). It judges your own behavior as right or wrong, good or bad, acceptable or unacceptable. And, should you fail to live up to these morals, the superego can be harshly punitive, imposing feelings of inferiority, guilt, shame, self-doubt, and anxiety. If we apply Freud’s terminology to the twins described in the chapter Prologue, Kenneth’s superego was clearly stronger than Julian’s.

superego

In Freud’s theory, the partly conscious, self-evaluative, moralistic component of personality that is formed through the internalization of parental and societal rules.

THE EGO DEFENSE MECHANISMSUNCONSCIOUS SELF-DECEPTIONS

The ego has a difficult task. It must be strong, flexible, and resourceful to successfully mediate conflicts among the instinctual demands of the id, the moral authority of the superego, and external restrictions. According to Freud (1923), everyone experiences an ongoing daily battle among these three warring personality processes.

When the demands of the id or superego threaten to overwhelm the ego, anxiety results (Freud, 1915b). If instinctual id impulses overpower the ego, a person may act impulsively and perhaps destructively. Using Freud’s terminology, you could say that Julian’s id was out of control when he stole from the church and tried to rob the drugstore. In contrast, if superego demands overwhelm the ego, an individual may suffer from guilt, self-reproach, or even suicidal impulses for failing to live up to the superego’s moral standards (Freud, 1936). Using Freudian terminology again, it is probably safe to say that Kenneth’s feelings of guilt over Julian were inspired by his superego.

If a realistic solution or compromise is not possible, the ego may temporarily reduce anxiety by distorting thoughts or perceptions of reality through processes that Freud called ego defense mechanisms (A. Freud, 1946; Freud, 1915c). By resorting to these largely unconscious self-deceptions, the ego can maintain an integrated sense of self while searching for a more acceptable and realistic solution to a conflict between the id and superego.

ego defense mechanisms

Largely unconscious distortions of thoughts or perceptions that act to reduce anxiety.

The most fundamental ego defense mechanism is repression (Freud, 1915a, 1936). To some degree, repression occurs in every ego defense mechanism. In simple terms, repression is unconscious forgetting. Unbeknownst to the person, anxiety-producing thoughts, feelings, or impulses are pushed out of conscious awareness into the unconscious. Common examples include traumatic events, past failures, embarrassments, disappointments, the names of disliked people, episodes of physical pain or illness, and unacceptable urges.

repression (in psychoanalytic theory of personality and psychotherapy)

The unconscious exclusion of anxiety-provoking thoughts, feelings, and memories from conscious awareness; the most fundamental ego defense mechanism.

Repression, however, is not an all-or-nothing psychological process. As Freud (1939) explained, “The repressed material retains its impetus to penetrate into consciousness.” In other words, if you encounter a situation that is very similar to one you’ve repressed, bits and pieces of memories of the previous situation may begin to resurface. In such instances, the ego may employ other defense mechanisms that allow the urge or information to remain partially conscious.

This is what occurs with the ego defense mechanism of displacement. Displacement occurs when emotional impulses are redirected to a substitute object or person, usually one less threatening or dangerous than the original source of conflict (A. Freud, 1946). For example, an employee angered by a supervisor’s unfair treatment may displace his hostility onto family members when he comes home from work. The employee consciously experiences anger but directs it toward someone other than its true target, which remains unconscious.

displacement

The ego defense mechanism that involves unconsciously shifting the target of an emotional urge to a substitute target that is less threatening or dangerous.

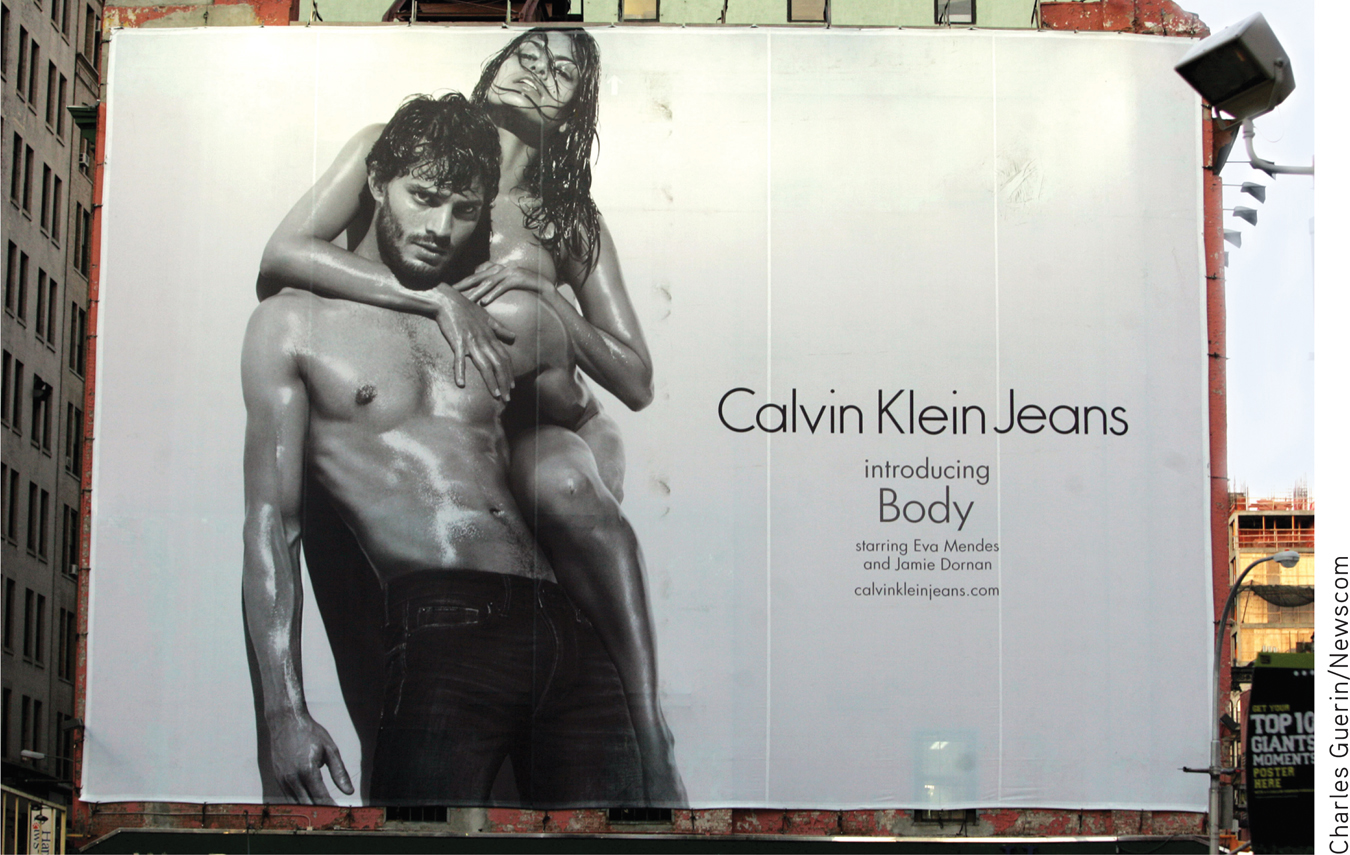

Freud (1930) believed that a special form of displacement, called sublimation, is largely responsible for the productive and creative contributions of people and even of whole societies. Sublimation involves displacing sexual urges toward “an aim other than, and remote from, that of sexual gratification” (Freud, 1914). In effect, sublimation channels sexual urges into productive, socially acceptable, nonsexual activities (Cohen & others, 2014).

sublimation

An ego defense mechanism that involves redirecting sexual urges toward productive, socially acceptable, nonsexual activities; a form of displacement.

The major defense mechanisms are summarized in TABLE 11.1. In Freud’s view, the drawback to using any defense mechanism is that maintaining these self-deceptions requires psychological energy. As Freud (1936) pointed out regarding the most basic defense mechanism, repression does not take place “on a single occasion” but rather demands “a continuous expenditure of effort.” Such effort depletes psychological energy that is needed to cope effectively with the demands of daily life.

The Major Ego Defense Mechanisms

| Defense | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Repression | The complete exclusion from consciousness of anxiety-producing thoughts, feelings, or impulses; most basic defense mechanism. | Three years after being hospitalized for back surgery, a man can remember only vague details about the event. |

| Displacement | The redirection of emotional impulses toward a substitute person or object, usually one less threatening or dangerous than the original source of conflict. | Angered by a neighbor’s hateful comment, a mother spanks her daughter for accidentally spilling her milk. |

| Sublimation | A form of displacement in which sexual urges are rechanneled into productive, nonsexual activities. | A graduate student works on her thesis 14 hours a day while her husband is on an extended business trip. |

| Rationalization | Justifying one’s actions or feelings with socially acceptable explanations rather than consciously acknowledging one’s true motives or desires. | After being rejected by a prestigious university, a student explains that he is glad because he would be happier at a smaller, less competitive college. |

| Projection | The attribution of one’s own unacceptable urges or qualities to others. | A married woman who is sexually attracted to a co-worker accuses him of flirting with her. |

| Reaction formation | Thinking or behaving in a way that is the extreme opposite of unacceptable urges or impulses. | Threatened by his awakening sexual attraction to girls, an adolescent boy goes out of his way to tease and torment adolescent girls. |

| Denial | The failure to recognize or acknowledge the existence of anxiety-provoking information. | Despite having multiple drinks every night, a man says he is not an alcoholic because he never drinks before 5 p.m. |

| Undoing | A form of unconscious repentance that involves neutralizing or atoning for an unacceptable action or thought with a second action or thought. | A woman who gets a tax refund by cheating on her taxes makes a larger-than-usual donation to the church collection on the following Sunday. |

| Regression | Retreating to a behavior pattern characteristic of an earlier stage of development. | After her parents’ bitter divorce, a 10-year-old girl refuses to sleep alone in her room, crawling into bed with her mother. |

The use of defense mechanisms is very common. Many psychologically healthy people temporarily use ego defense mechanisms to deal with stressful events. When ego defense mechanisms are used in limited areas and on a short-term basis, psychological energy is not seriously depleted. Ideally, we strive to maintain realistic perceptions of the world and our motives, and search for workable solutions to conflicts and problems. Using ego defense mechanisms is often a way of buying time while we consciously or unconsciously wrestle with more realistic solutions for whatever is troubling us. But when defense mechanisms delay or interfere with our use of more constructive coping strategies, they can be counterproductive.

Personality Development

THE PSYCHOSEXUAL STAGES

KEY THEME

The psychosexual stages are age-related developmental periods, and each stage represents a different focus of the id’s sexual energies.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the five psychosexual stages, and what are the core conflicts of each stage?

What is the consequence of fixation?

What role does the Oedipus complex play in personality development?

According to Freud (1905), people progress through five psychosexual stages of development. The foundations of adult personality are established during the first five years of life, as the child progresses through the oral, anal, and phallic psychosexual stages. The latency stage occurs during late childhood, and the fifth and final stage, the genital stage, begins in adolescence.

Each psychosexual stage represents a different focus of the id’s sexual energies. Freud (1940) contended that “sexual life does not begin only at puberty, but starts with clear manifestations after birth.” This statement is often misinterpreted. Freud was not saying that an infant experiences sexual urges in the same way that an adult does. Instead, Freud believed that the infant or young child expresses primitive sexual urges by seeking sensual pleasure from different areas of the body. Thus, the psychosexual stages are age-related developmental periods in which sexual impulses are focused on different bodily zones and are expressed through the activities associated with these areas.

psychosexual stages

In Freud’s theory, age-related developmental periods in which the child’s sexual urges are focused on different areas of the body and are expressed through the activities associated with those areas.

Over the first five years of life, the expression of primitive sexual urges progresses from one bodily zone to another in a distinct order: the mouth, the anus, and the genitals. The first year of life is characterized as the oral stage. During this time the infant derives pleasure through the oral activities of sucking, chewing, and biting. During the next two years, pleasure is derived through elimination and acquiring control over elimination—the anal stage. In the phallic stage, pleasure seeking is focused on the genitals.

FIXATIONUNRESOLVED DEVELOPMENTAL CONFLICTS

At each psychosexual stage, Freud (1905) believed, the infant or young child is faced with a developmental conflict that must be successfully resolved in order to move on to the next stage. The heart of this conflict is the degree to which parents either frustrate or overindulge the child’s expression of pleasurable feelings. Hence, Freud (1940) believed that parental attitudes and the timing of specific child-rearing events, such as weaning or toilet training, leave a lasting influence on personality development.

If frustrated, the child will be left with feelings of unmet needs characteristic of that stage. If overindulged, the child may be reluctant to move on to the next stage. In either case, the result of an unresolved developmental conflict is fixation at a particular stage. The person continues to seek pleasure through behaviors that are similar to those associated with that psychosexual stage. For example, the adult who constantly chews gum, smokes, or bites her fingernails may have unresolved oral psychosexual conflicts.

THE OEDIPUS COMPLEXA PSYCHOSEXUAL DRAMA

The most critical conflict that the child must successfully resolve for healthy personality and sexual development occurs during the phallic stage (Freud, 1923, 1940). As the child becomes more aware of pleasure derived from the genital area, Freud believed, the child develops a sexual attraction to the opposite-sex parent and hostility toward the same-sex parent. This is the famous Oedipus complex, named after the protagonist of a Greek myth. Abandoned at birth, Oedipus does not know the identity of his parents. As an adult, he unknowingly kills his father and marries his mother.

Oedipus complex

In Freud’s theory, a child’s unconscious sexual desire for the opposite-sex parent, usually accompanied by hostile feelings toward the same-sex parent.

According to Freud, this attraction to the opposite-sex parent plays out as a sexual drama in the child’s mind, a drama with different plot twists for boys and for girls. For boys, the Oedipus complex unfolds as a confrontation with the father for the affections of the mother. The little boy feels hostility and jealousy toward his father, but he realizes that his father is more physically powerful. The boy experiences castration anxiety, or the fear that his father will punish him by castrating him (Freud, 1933).

It often happens that a young man falls in love seriously for the first time with a mature woman, or a girl with an elderly man in a position of authority; this is a clear echo of the [earlier] phase of development that we have been discussing, since these figures are able to re-animate pictures of their mother or father.

—Sigmund Freud (1905)

To resolve the Oedipus complex and these anxieties, the little boy ultimately joins forces with his former enemy by resorting to the defense mechanism of identification. That is, he imitates and internalizes his father’s values, attitudes, and mannerisms. There is, however, one strict limitation in identifying with the father. Only the father can enjoy the sexual affections of the mother. This limitation becomes internalized as a taboo against incestuous urges in the boy’s developing superego, a taboo that is enforced by the superego’s use of guilt and societal restrictions (Freud, 1905, 1923).

identification

In psychoanalytic theory, an ego defense mechanism that involves reducing anxiety by imitating the behavior and characteristics of another person.

Girls also ultimately resolve the Oedipus complex by identifying with the same-sex parent and developing a strong superego taboo against incestuous urges. But the underlying sexual drama in girls follows different themes. The little girl discovers that little boys have a penis and that she does not. She feels a sense of deprivation and loss that Freud termed penis envy.

According to Freud (1940), the little girl blames her mother for “sending her into the world so insufficiently equipped.” Thus, she develops contempt for and resentment toward her mother. However, in her attempt to take her mother’s place with her father, she also identifies with her mother. Like the little boy, the little girl internalizes the attributes of the same-sex parent.

Freud’s views on female sexuality, particularly the concept of penis envy, are among his most severely criticized ideas. Perhaps recognizing that his explanation of female psycho-sexual development rested on shaky ground, Freud (1926) admitted, “We know less about the sexual life of little girls than of boys. But we need not feel ashamed of this distinction. After all, the sexual life of adult women is a ‘dark continent’ for psychology.”

THE LATENCY AND GENITAL STAGES

Freud felt that because of the intense anxiety associated with the Oedipus complex, the sexual urges of boys and girls become repressed during the latency stage in late childhood. Outwardly, children in the latency stage express a strong desire to associate with same-sex peers, a preference that strengthens the child’s sexual identity.

The final resolution of the Oedipus complex occurs in adolescence, during the genital stage. As incestuous urges start to resurface, they are prohibited by the moral ideals of the superego as well as by societal restrictions. Thus, the person directs sexual urges toward socially acceptable substitutes, who often resemble the person’s opposite-sex parent (Freud, 1905).

In Freud’s theory, a healthy personality and sense of sexuality result when conflicts are successfully resolved at each stage of psychosexual development (summarized in TABLE 11.2). Successfully negotiating the conflicts at each psychosexual stage results in the person’s capacity to love and in productive living through one’s work, child rearing, and other accomplishments.

Freud’s Psychosexual Stages

| Age | Stage | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Birth to age 1 | Oral | The mouth is the primary focus of pleasurable and gratifying sensations, which the infant achieves via feeding and exploring objects with his or her mouth. |

| Ages 1 to 3 | Anal | The anus is the primary focus of pleasurable sensations, which the young child derives through developing control over elimination via toilet training. |

| Ages 3 to 6 | Phallic | The genitals are the primary focus of pleasurable sensations, which the child derives through sexual curiosity, masturbation, and sexual attraction to the opposite-sex parent. |

| Ages 7 to 11 | Latency | Sexual impulses become repressed and dormant as the child develops same-sex friendships with peers and focuses on school, sports, and other activities. |

| Adolescence | Genital | As the adolescent reaches physical sexual maturity, the genitals become the primary focus of pleasurable sensations, which the person seeks to satisfy in heterosexual relationships. |

CONCEPT REVIEW 11.1

Freud’s Psychoanalytic Theory

Select the correct answer.

Question 11.1

The id is guided by the ______________, and the ego is guided by the ____________.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.2

Freud developed the method of _________________ to help his patients uncover forgotten memories.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.3

The structure of personality that evaluates the morality of behavior is called the _____________.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.4

Eight-year-old Johnny wants to be a truck driver when he grows up, just like his dad. Johnny’s acceptance of his father’s attitudes and values indicates the process of _____________.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.5

Every time 4-year-old Felix touches his genitals, his parents call him a “dirty little boy” and slap his hands. According to Freud, Felix’s frustration may result in an unresolved developmental conflict called _______________.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.6

Seven-year-old Carolyn prefers to play with girls and does not like playing with boys very much. Carolyn is probably in the ________________ stage of sexual development.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

The Neo-Freudians

FREUD’S DESCENDANTS AND DISSENTERS

KEY THEME

The neo-Freudians followed Freud in stressing the importance of the unconscious and early childhood, but they developed their own personality theories.

KEY QUESTIONS

How did the neo-Freudians generally depart from Freud’s ideas?

What were the key ideas of Jung, Horney, and Adler?

What are three key criticisms of Freud’s theory and of the psychoanalytic perspective?

Freud’s ideas were always controversial. But by the early 1900s, he had attracted a number of followers, many of whom went to Vienna to study with him. Although these early followers developed their own personality theories, they still recognized the importance of many of Freud’s basic notions, such as the influence of unconscious processes and early childhood experiences. In effect, they kept the foundations that Freud had established but offered new explanations for personality processes. Hence, these theorists are often called neo-Freudians (the prefix neo means “new”). The neo-Freudians and their theories are considered part of the psychoanalytic perspective on personality.

In general, the neo-Freudians disagreed with Freud on three key points. First, they took issue with Freud’s belief that behavior was primarily motivated by sexual urges. Second, they disagreed with Freud’s contention that personality is fundamentally determined by early childhood experiences. Instead, the neo-Freudians believed that personality can also be influenced by experiences throughout the lifespan. Third, the neo-Freudian theorists departed from Freud’s generally pessimistic view of human nature and society.

In Chapter 9, on lifespan development, we described the psychosocial theory of one famous neo-Freudian, Erik Erikson. In this chapter, we’ll look at the basic ideas of three other important neo-Freudians: Carl Jung, Karen Horney, and Alfred Adler.

CARL JUNGARCHETYPES AND THE COLLECTIVE UNCONSCIOUS

Born in a small town in Switzerland, Carl Jung (1875–

Intrigued by Freud’s ideas, Jung began a correspondence with him. At their first meeting, the two men were so compatible that they talked for 13 hours nonstop. Freud felt that his young disciple was so promising that he called him his “adopted son” and his “crown prince.” It would be Jung, Freud decided, who would succeed him and lead the international psychoanalytic movement. However, Jung was too independent to relish his role as Freud’s unquestioning disciple. As Jung continued to put forth his own ideas, his close friendship with Freud ultimately ended in bitterness (Solomon, 2003).

Jung rejected Freud’s belief that human behavior is fueled by the instinctual drives of sex and aggression. Instead, Jung believed that people are motivated by a more general psychological energy that pushes them to achieve psychological growth, self-realization, and psychic wholeness and harmony. Jung (1963) also believed that personality continues to develop in significant ways throughout the lifespan.

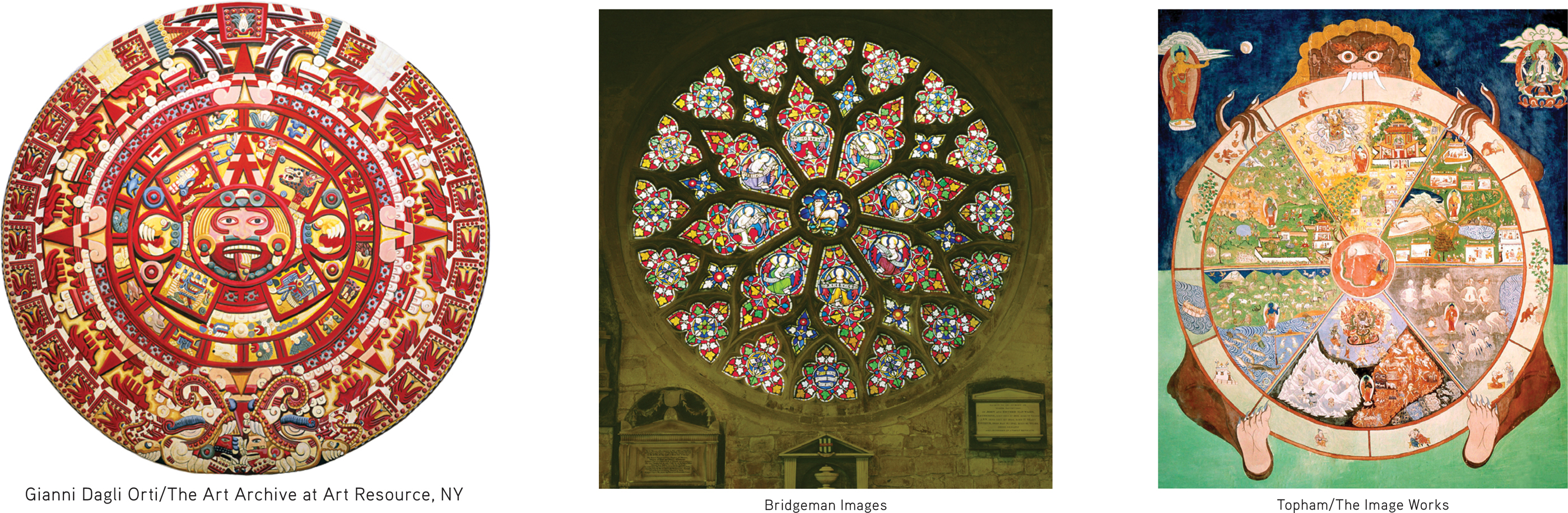

In studying different cultures, Jung was struck by the universality of many images and themes, which also surfaced in his patients’ dreams and preoccupations. These observations led to some of Jung’s most intriguing ideas, the notions of the collective unconscious and archetypes.

What we properly call instincts are physiological urges, and are perceived by the senses. But at the same time, they also manifest themselves in fantasies and often reveal their presence only by symbolic images. These manifestations are what I call the archetypes. They are without known origin; and they reproduce themselves in any time or in any part of the world.

—Carl Jung (1964)

Jung (1936) believed that the deepest part of the individual psyche is the collective unconscious, which is shared by all people and reflects humanity’s collective evolutionary history. He described the collective unconscious as containing “the whole spiritual heritage of mankind’s evolution, born anew in the brain structure of every individual” (Jung, 1931).

collective unconscious

In Jung’s theory, the hypothesized part of the unconscious mind that is inherited from previous generations and that contains universally shared ancestral experiences and ideas.

Contained in the collective unconscious are the archetypes, the mental images of universal human instincts, themes, and preoccupations (Jung, 1964). Common archetypal themes that are expressed in virtually every culture are the hero, the powerful father, the nurturing mother, the witch, the wise old man, the innocent child, and death and rebirth.

archetypes

(AR-kuh-types) In Jung’s theory, the inherited mental images of universal human instincts, themes, and preoccupations that are the main components of the collective unconscious.

Two important archetypes that Jung (1951) described are the anima and the animus—the representations of feminine and masculine qualities. Jung believed that every man has a “feminine” side, represented by his anima, and that every woman has a “masculine” side, represented by her animus. To achieve psychological harmony, Jung believed, it is important for men to recognize and accept their feminine aspects and for women to recognize and accept the masculine side of their nature.

Not surprisingly, Jung’s concepts of the collective unconscious and shared archetypes have been criticized as being unscientific or mystical. As far as we know, individual experiences cannot be genetically passed down from one generation to the next. Regardless, Jung’s ideas make more sense if you think of the collective unconscious as reflecting shared human experiences. The archetypes, then, can be thought of as symbols that represent the common, universal themes of the human life cycle. These universal themes include birth, achieving a sense of self, parenthood, the spiritual search, and death.

Although Jung’s theory never became as influential as Freud’s, some of his ideas have gained wide acceptance. For example, Jung (1923) was the first to describe two basic personality types: introverts, who focus their attention inward, and extraverts, who turn their attention and energy toward the outside world. We will encounter these two basic personality dimensions again when we look at trait theories later in this chapter. Finally, Jung’s emphasis on the drive toward psychological growth and self-realization anticipated some of the basic ideas of the humanistic perspective on personality, which we’ll look at shortly.

(c) Bridgeman Images

(tr) Topham/The Image Works

KAREN HORNEYBASIC ANXIETY AND “WOMB ENVY”

Trained as a Freudian psychoanalyst, Karen Horney (1885–

Horney also stressed the importance of social relationships, especially the parent–

Horney (1945) described three patterns of behavior that the individual uses to defend against basic anxiety: moving toward, against, or away from other people. Those who move toward other people have an excessive need for approval and affection. Those who move against others have an excessive need for power, especially power over other people. They are often competitive, critical, and domineering, and they need to feel superior to others. Finally, those who move away from other people have an excessive need for independence and self-sufficiency, which often makes them aloof and detached from others.

Horney contended that people with a healthy personality are flexible in balancing these different needs, for there are times when each behavior pattern is appropriate. As Horney (1945) wrote, “One should be capable of giving in to others, of fighting, and keeping to oneself. The three can complement each other and make for a harmonious whole.” But when one pattern becomes the predominant way of dealing with other people and the world, psychological conflict and problems can result.

Man, [Freud] postulated, is doomed to suffer or destroy. … My own belief is that man has the capacity as well as the desire to develop his potentialities and become a decent human being, and that these deteriorate if his relationship to others and hence to himself is, and continues to be, disturbed. I believe that man can change and go on changing as long as he lives.

—Karen Horney (1945)

Horney also sharply disagreed with Freud’s interpretation of female development, especially his notion that women suffer from penis envy. What women envy in men, Horney (1926) claimed, is not their penis, but their superior status in society. In fact, Horney contended that men often suffer womb envy, envying women’s capacity to bear children. Neatly standing Freud’s view of feminine psychology on its head, Horney argued that men compensate for their relatively minor role in reproduction by constantly striving to make creative achievements in their work (Gilman, 2001). As Horney (1945) wrote, “Is not the tremendous strength in men of the impulse to creative work in every field precisely due to their feelings of playing a relatively small part in the creation of living beings, which constantly impels them to an overcompensation in achievement?”

Horney shared Jung’s belief that people are not doomed to psychological conflict and problems. Also like Jung, Horney believed that the drive to grow psychologically and achieve one’s potential is a basic human motive.

ALFRED ADLERFEELINGS OF INFERIORITY AND STRIVING FOR SUPERIORITY

Born in Vienna, Alfred Adler (1870–

Adler (1933b) believed that the most fundamental human motive is striving for superiority—the desire to improve oneself, master challenges, and move toward self-perfection and self-realization. Striving toward superiority arises from universal feelings of inferiority that are experienced during infancy and childhood, when the child is helpless and dependent on others. These feelings motivate people to compensate for their real or imagined weaknesses by emphasizing their talents and abilities and by working hard to improve themselves (Watts, 2012). Hence, Adler (1933a) saw the universal human feelings of inferiority as ultimately constructive and valuable.

However, when people are unable to compensate for specific weaknesses or when their feelings of inferiority are excessive, they can develop an inferiority complex—a general sense of inadequacy, weakness, and helplessness. People with an inferiority complex are often unable to strive for mastery and self-improvement.

At the other extreme, people can overcompensate for their feelings of inferiority and develop a superiority complex. Behaviors caused by a superiority complex might include exaggerating one’s accomplishments and importance in an effort to cover up weaknesses and denying the reality of one’s limitations (Adler, 1954).

To be a human being means to have inferiority feelings. One recognizes one’s own powerlessness in the face of nature. One sees death as the irrefutable consequence of existence. But in the mentally healthy person this inferiority feeling acts as a motive for productivity, as a motive for attempting to overcome obstacles, to maintain oneself in life.

—Alfred Adler (1933a)

Like Horney, Adler believed that humans were motivated to grow and achieve their personal goals. And, like Horney, Adler emphasized the importance of cultural influences and social relationships (Carlson & others, 2008; West & Bubenzer, 2012).

CONCEPT REVIEW 11.2

Psychoanalytic Theorists

Which psychoanalytic theorist made each of the following statements?

Question 11.7

| 1. | “The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind.” |

Question 11.8

| 2. | “My own belief is that man has the capacity as well as the desire to develop his potentialities and become a decent human being, and that these deteriorate if his relationship to others and hence to himself is, and continues to be, disturbed.” |

Question 11.9

| 3. | “To be human means to have inferiority feelings.” |

Question 11.10

| 4. | “The whole spiritual heritage of mankind’s evolution [is] born anew in the brain structure of every individual.” |

Question 11.11

| 5. | “Sexual life does not begin only at puberty, but starts with clear manifestations after birth.” |

Question 11.12

| 6. | “One should be capable of giving in to others, of fighting, and of keeping to oneself. The three can complement each other and make for a harmonious whole.” |

Evaluating Freud and the Psychoanalytic Perspective on Personality

Like it or not, Sigmund Freud’s ideas have had a profound and lasting impact on our culture and on our understanding of human nature (see Merlino & others, 2008). Today, opinions on Freud span the entire spectrum. Some see him as a genius who discovered brilliant, lasting insights into human nature. Others contend that Freud was a deeply neurotic, driven man who successfully foisted his twisted personal view of human nature onto an unsuspecting public (Crews, 1984, 1996, 2006).

The truth, as you might suspect, lies somewhere in between. Although Freud has had an enormous impact on psychology and on society, there are several valid criticisms of Freud’s theory and, more generally, of the psychoanalytic perspective. We’ll discuss three of the most important problems next.

INADEQUACY OF EVIDENCE

Freud’s theory relies wholly on data derived from his relatively small number of patients and from self-analysis. Most of Freud’s patients were relatively well-to-do, well-educated members of the middle and upper classes in Vienna at the beginning of the twentieth century. Freud (1916, 1919, 1939) also analyzed the lives of famous historical figures, such as Leonardo da Vinci, and looked to myth, religion, literature, and evolutionary prehistory for confirmation of his ideas. Any way you look at it, this is a small and rather skewed sample from which to draw sweeping generalizations about human nature.

Furthermore, it is impossible to objectively assess Freud’s “data.” Freud did not take notes during his private therapy sessions. And, of course, when Freud did report a case in detail, it was still his own interpretation of the case that was recorded. For Freud, proof of the validity of his ideas depended on his uncovering similar patterns in different patients. So the critical question is this: Was Freud imposing his own ideas onto his patients, seeing only what he expected to see? Some critics think so (see Grünbaum, 2006, 2007).

For good or ill, Sigmund Freud, more than any other explorer of the psyche, has shaped the mind of the 20th century. The very fierceness and persistence of his detractors are a wry tribute to the staying power of Freud’s ideas.

—Peter Gay (1999)

LACK OF TESTABILITY

Many psychoanalytic concepts are so vague and ambiguous that they are impossible to objectively measure or confirm (Crews, 2006; Grünbaum, 2006). For example, how might you go about proving the existence of the id or the superego? Or how could you operationally define and measure the effects of the pleasure principle, the life instinct, or the Oedipus complex?

Psychoanalytic “proof” often has a “heads I win, tails you lose” style to it. In other words, psychoanalytic concepts are often impossible to disprove because even seemingly contradictory information can be used to support Freud’s theory. For example, if your memory of childhood doesn’t jibe with Freud’s description of the psychosexual stages or the Oedipus complex, well, that’s because you’ve repressed it. Freud himself was not immune to this form of reasoning (Robinson, 1993). When one of Freud’s patients reported dreams that didn’t seem to reveal a hidden wish, Freud interpreted the dreams as betraying the patient’s hidden wish to disprove Freud’s dream theory!

Step by step, we are learning that Freud has been the most overrated figure in the entire history of science and medicine—one who wrought immense harm through the propagation of false etiologies, mistaken diagnoses, and fruitless lines of inquiry.

—Frederick Crews (2006)

As Freud acknowledged, psychoanalysis is better at explaining past behavior than at predicting future behavior (Gay, 1989). Indeed, psychoanalytic interpretations are so flexible that a given behavior can be explained by any number of completely different motives. For example, a man who is extremely affectionate toward his wife might be exhibiting displacement of a repressed incestuous urge (he is displacing his repressed affection for his mother onto his wife), reaction formation (he actually hates his wife intensely, so he compensates by being overly affectionate), or fixation at the oral stage (he is overly dependent on his wife).

Nonetheless, several key psychoanalytic ideas have been substantiated by empirical research (Cogan & others, 2007; Westen, 1990, 1998). Among these are the ideas that (1) much of mental life is unconscious; (2) early childhood experiences have a critical influence on interpersonal relationships and psychological adjustment; and (3) people differ significantly in the degree to which they are able to regulate their impulses, emotions, and thoughts toward adaptive and socially acceptable ends.

SEXISM

Many people feel that Freud’s theories reflect a sexist view of women. Because penis envy produces feelings of shame and inferiority, Freud (1925) claimed, women are more vain, masochistic, and jealous than men. He also believed that women are more influenced by their emotions and have a lesser ethical and moral sense than men.

As Horney and other female psychoanalysts have pointed out, Freud’s theory uses male psychology as a prototype. Women are essentially viewed as a deviation from the norm of masculinity (Horney, 1926; Thompson, 1950). Perhaps, Horney suggested, psychoanalysis would have evolved an entirely different view of women if it were not dominated by the male point of view.

To Freud’s credit, women were quite active in the early psychoanalytic movement. Several female analysts became close colleagues of Freud (Freeman & Strean, 1987; Roazen, 1999, 2000). And, it was Freud’s daughter Anna, rather than any of his sons, who followed in his footsteps as an eminent psychoanalyst. Ultimately, Anna Freud became her father’s successor as leader of the international psychoanalytic movement.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that most psychologists today agree with Sigmund Freud’s personality theory?

The weaknesses in Freud’s theory and in the psychoanalytic approach to personality are not minor problems. As you’ll see in Chapter 15 on Therapies, very few psychologists practice Freudian psychoanalysis today. All the same, Freud made some extremely significant contributions to modern psychological thinking. Most important, he drew attention to the existence and influence of mental processes that occur outside conscious awareness, an idea that continues to be actively investigated by today’s psychological researchers.

Test your understanding of Personality and the Psychoanalytic Perspective with

.

.