11.3 The Humanistic Perspective on Personality

KEY THEME

The humanistic perspective emphasizes free will, self-awareness, and psychological growth.

KEY QUESTIONS

What roles do self-concept, actualizing tendency, and unconditional positive regard play in Rogers’s personality theory?

What are key strengths and weaknesses of the humanistic perspective?

By the 1950s, the field of personality was dominated by two completely different perspectives: Freudian psychoanalysis and B. F. Skinner’s brand of behaviorism (see Chapter 5). While Freud’s theory of personality proposed elaborate and complex internal states, Skinner believed that psychologists should focus on observable behaviors and on the environmental factors that shape and maintain those behaviors (see Rogers & Skinner, 1956). As Skinner (1971) wrote, “A person does not act upon the world, the world acts upon him.”

The Emergence of the “Third Force”

Another group of psychologists had a fundamentally different view of human nature. In opposition to both psychoanalysis and behaviorism, they championed a “third force” in psychology, which they called humanistic psychology. Humanistic psychology is a view of personality that emphasizes human potential and such uniquely human characteristics as self-awareness and free will (Cain, 2002).

humanistic psychology (theory of personality)

The theoretical viewpoint on personality that generally emphasizes the inherent goodness of people, human potential, self-actualization, the self-concept, and healthy personality development.

In contrast to Freud’s pessimistic view of people as being motivated by unconscious sexual and destructive instincts, the humanistic psychologists saw people as being innately good. Humanistic psychologists also differed from psychoanalytic theorists by their focus on the healthy personality rather than on psychologically troubled people.

In contrast to the behaviorist view that human and animal behavior is due largely to environmental reinforcement and punishment, the humanistic psychologists believed that people are motivated by the need to grow psychologically. They also doubted that laboratory research with rats and pigeons accurately reflected the essence of human nature, as the behaviorists claimed. Instead, humanistic psychologists contended that the most important factor in personality is the individual’s conscious, subjective perception of his or her self (Purkey & Stanley, 2002).

The two most important contributors to the humanistic perspective were Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow. In Chapter 8, on motivation, we discussed Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs and his concept of self-actualization. Like Maslow, Rogers emphasized the tendency of human beings to strive to fulfill their potential and capabilities (Kirschenbaum, 2004; Kirschenbaum & Jourdan, 2005).

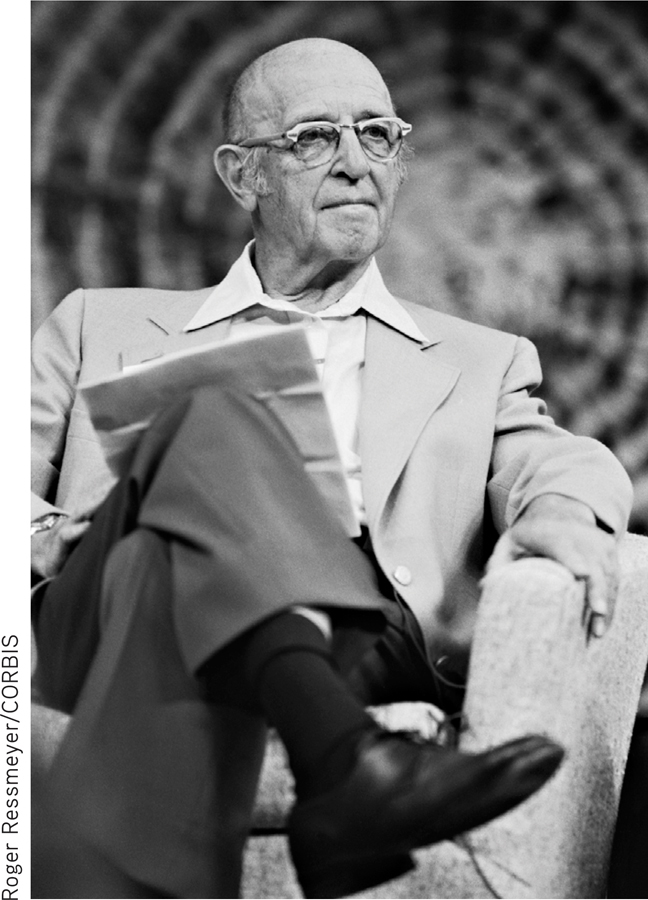

Carl Rogers: ON BECOMING A PERSON

Carl Rogers (1902–

Like Freud, Rogers developed his personality theory from his clinical experiences with his patients. Rogers referred to his patients as “clients” to emphasize their active and voluntary participation in therapy. In marked contrast to Freud, Rogers was continually impressed by his clients’ drive to grow and develop their potential.

These observations convinced Rogers that the most basic human motive is the actualizing tendency—the innate drive to maintain and enhance the human organism (Bohart, 2007; Bozarth & Wang, 2008). According to Rogers, all other human motives, whether biological or social, are secondary. He compared the actualizing tendency to a child’s drive to learn to walk despite early frustration and falls. To get a sense of the vastly different views of Rogers and Freud, read the Critical Thinking box, “Freud Versus Rogers on Human Nature.”

actualizing tendency

In Rogers’s theory, the innate drive to maintain and enhance the human organism.

At bottom, each person is asking, “Who am I, really? How can I get in touch with this real self, underlying all my surface behavior? How can I become myself?”

—Carl Rogers (1961)

THE SELF-CONCEPT

Rogers (1959) was struck by how frequently his clients in therapy said, “I’m not really sure who I am” or “I just don’t feel like myself.” This observation helped form the cornerstone of Rogers’s personality theory: the idea of the self-concept. The self-concept is the set of perceptions and beliefs that you have about yourself, including your nature, your personal qualities, and your typical behavior.

self-concept

The set of perceptions and beliefs that you hold about yourself.

According to Rogers (1980), people are motivated to act in accordance with their self-concept. So strong is the need to maintain a consistent self-concept that people will deny or distort experiences that contradict their self-concept.

The self-concept begins evolving early in life. Because they are motivated by the actualizing tendency, infants and young children naturally gravitate toward self-enhancing experiences. But as children develop greater self-awareness, there is an increasing need for positive regard. Positive regard is the sense of being loved and valued by other people, especially one’s parents (Bozarth, 2007; Farber & Doolin, 2011).

CRITICAL THINKING

Freud Versus Rogers on Human Nature

Freud’s view of human nature was deeply pessimistic. He believed that the human aggressive instinct was innate, persistent, and pervasive. Were it not for internal superego restraints and external societal restraints, civilization as we know it would collapse: The destructive instincts of humans would be unleashed. As Freud (1930) wrote in Civilization and Its Discontents:

Men are not gentle creatures who want to be loved, and who at the most can defend themselves if they are attacked; they are, on the contrary, creatures among whose instinctual endowments is to be reckoned a powerful share of aggressiveness. As a result, their neighbor is for them not only a potential helper or sexual object, but also someone who tempts them to satisfy their aggressiveness on him, to exploit his capacity for work without compensation, to use him sexually without his consent, to seize his possessions, to humiliate him, to cause him pain, to torture and to kill him. Man is a wolf to man. Who, in the face of all his experience of life and of history, will have the courage to dispute this assertion?

In Freud’s view, then, the essence of human nature is destructive. Control of these destructive instincts is necessary. Yet societal, cultural, religious, and moral restraints also make people frustrated, neurotic, and unhappy. Why? Because the strivings of the id toward instinctual satisfaction must be frustrated if civilization and the human race are to survive. Hence, as the title of Freud’s book emphasizes, civilization is inevitably accompanied by human “discontent.”

A pretty gloomy picture, isn’t it? Yet if you watch the evening news or read the newspaper, you may find it hard to disagree with Freud’s negative image of human nature. People are often exceedingly cruel and selfish, committing horrifying acts of brutality against strangers and even against loved ones.

However, you might argue that people can also be extraordinarily kind, self-sacrificing, and loving toward others. Freud would agree with this observation. Yet according to his theory, “good” or “moral” behavior does not disprove the essentially destructive nature of people. Instead, he explains good or moral behavior in terms of superego control, sublimation of the instincts, displacement, and so forth.

On the one hand, violence motivated by political or ethnic hatred seems to support Freud’s contentions about human nature.

On the other hand, the selfless behavior of those who help others, often at a considerable cost to themselves, seems to support Rogers’s view. Which viewpoint do you think more accurately describes the essence of human nature?

But is this truly the essence of human nature? Carl Rogers disagreed strongly. “I do not discover man to be well characterized in his basic nature by such terms as fundamentally hostile, antisocial, destructive, evil,” Rogers (1957a) wrote. Instead, Rogers believed that people are more accurately described as “positive, forward-moving, constructive, realistic, trustworthy.”

If this is so, how can Rogers account for the evil and cruelty in the world? Rogers didn’t deny that people can behave destructively and cruelly. Yet throughout his life, Rogers insisted that people are innately good. Rogers (1981) explained the existence of evil in this way:

My experience leads me to believe that it is cultural factors which are the major factor in our evil behaviors. The rough manner of childbirth, the infant’s mixed experience with the parents, the constricting, destructive influence of our educational system, the injustice of our distribution of wealth, our cultivated prejudices against individuals who are different—all these elements and many others warp the human organism in directions which are antisocial.

In sharp contrast to Freud, Rogers (1964) said we should trust the human organism because the human who is truly free to choose will naturally gravitate toward behavior that serves to perpetuate the human race and improve society as a whole:

I dare to believe that when the human being is inwardly free to choose whatever he deeply values, he tends to value those objects, experiences, and goals that will make for his own survival, growth, and development, and for the survival and development of others. … The psychologically mature person as I have described him has, I believe, the qualities which would cause him to value those experiences which would make for the survival and enhancement of the human race.

Two great thinkers, two diametrically opposed views of human nature. Now it’s your turn to critically evaluate their views.

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

Are people inherently driven by aggressive instincts, as Freud claimed? Must the destructive urges of the id be restrained by parents, culture, religion, and society if civilization is to continue? Would an environment in which individuals were unrestrained inevitably lead to an unleashing of destructive instincts?

Or are people naturally good, as Rogers claimed? If people existed in a truly free and nurturing environment, would they invariably make constructive choices that would benefit both themselves and society as a whole?

Rogers (1959) maintained that most parents provide their children with conditional positive regard—the sense that the child is valued and loved only when she behaves in a way that is acceptable to others. The problem with conditional positive regard is that it causes the child to learn to deny or distort her genuine feelings. For example, if little Amy’s parents scold and reject her when she expresses angry feelings, her strong need for positive regard will cause her to deny her anger, even when it’s justified or appropriate. Eventually, Amy’s self-concept will become so distorted that genuine feelings of anger are denied because they are inconsistent with her self-concept as “a good girl who never gets angry.” Because of the fear of losing positive regard, she cuts herself off from her true feelings.

conditional positive regard

In Rogers’s theory, the sense that you will be valued and loved only if you behave in a way that is acceptable to others; conditional love or acceptance.

Like Freud, Rogers believed that feelings and experiences could be driven from consciousness by being denied or distorted. But Rogers believed that feelings become denied or distorted not because they are threatening but because they contradict the self-concept. In this case, people are in a state of incongruence: Their self-concept conflicts with their actual experience (Rogers, 1959). Such a person is continually defending against genuine feelings and experiences that are inconsistent with his self-concept. As this process continues over time, a person progressively becomes more “out of touch” with his true feelings and his essential self, often experiencing psychological problems as a result.

How is incongruence to be avoided? In the ideal situation, a child experiences a great deal of unconditional positive regard from parents and other authority figures. Unconditional positive regard refers to the child’s sense of being unconditionally loved and valued, even if she doesn’t conform to the standards and expectations of others. In this way, the child’s actualizing tendency is allowed its fullest expression. However, Rogers did not advocate permissive parenting. He thought that parents were responsible for controlling their children’s behavior and for teaching them acceptable standards of behavior. Rogers maintained that parents can discipline their child without undermining the child’s sense of self-worth.

unconditional positive regard

In Rogers’s theory, the sense that you will be valued and loved even if you don’t conform to the standards and expectations of others; unconditional love or acceptance.

For example, parents can disapprove of a child’s specific behavior without completely rejecting the child herself. In effect, the parent’s message should be, “I do not value your behavior right now, but I still love and value you.” In this way, according to Rogers, the child’s essential sense of self-worth can remain intact.

!launch!

Rogers (1957b) believed that it is through consistent experiences of unconditional positive regard that one becomes a psychologically healthy, fully functioning person. The fully functioning person has a flexible, constantly evolving self-concept. She is realistic, open to new experiences, and capable of changing in response to new experiences.

Rather than defending against or distorting her own thoughts or feelings, the person experiences congruence: Her sense of self is consistent with her emotions and experiences (Farber, 2007). The actualizing tendency is fully operational, and she makes choices that move her in the direction of greater growth and fulfillment of potential. Rogers (1957b, 1964) believed that the fully functioning person is likely to be creative and spontaneous, and to enjoy harmonious relationships with others.

Evaluating the Humanistic Perspective on Personality

The humanistic perspective has been criticized on two particular points. First, humanistic theories are hard to validate or test scientifically. Humanistic theories tend to be based on philosophical assumptions or clinical observations rather than on empirical research. For example, concepts like the self-concept, unconditional positive regard, and the actualizing tendency are very difficult to define or measure objectively.

I am quite aware that out of defensiveness and inner fear individuals can and do behave in ways which are incredibly cruel, horribly destructive, immature, regressive, antisocial, and hurtful. Yet one of the most refreshing and invigorating parts of my experience is to work with such individuals and to discover the strongly positive directional tendencies which exist in them, as in all of us, at the deepest levels.

—Carl Rogers (1961)

Second, many psychologists believe that humanistic psychology’s view of human nature is too optimistic (Bohart, 2013). For example, if self-actualization is a universal human motive, why are self-actualized people so hard to find? And, critics claim, humanistic psychologists have minimized the darker, more destructive side of human nature. Can we really account for all the evil in the world by attributing it to a restrictive upbringing or society?

The influence of humanistic psychology has waned since the 1960s and early 1970s (Cain, 2003). Nevertheless, it has made lasting contributions, especially in the realms of psychotherapy, counseling, education, and parenting (Farber, 2007; Joseph & Murphy, 2013). The humanistic perspective has also promoted the scientific study of such topics as the healthy personality and creativity. Finally, the importance of subjective experience and the self-concept has become widely accepted in different areas of psychology (Sheldon, 2008; Sleeth, 2007).