11.6 Assessing Personality

PSYCHOLOGICAL TESTS

KEY THEME

Tests to measure and evaluate personality fall into two basic categories: projective tests and self-report inventories.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the most widely used personality tests, and how are they administered and interpreted?

What are some key strengths and weaknesses of projective tests and self-report inventories?

When we discussed intelligence tests in Chapter 7, we described the characteristics of a good psychological test. Beyond intelligence tests, there are literally hundreds of psychological tests that can be used to assess abilities, aptitudes, interests, and personality (Spies & others, 2010). Any psychological test is useful insofar as it achieves two basic goals:

It accurately and consistently reflects a person’s characteristics on some dimension.

It predicts a person’s future psychological functioning or behavior.

psychological test

A test that assesses a person’s abilities, aptitudes, interests, or personality on the basis of a systematically obtained sample of behavior.

In this section, we’ll look at the very different approaches used in the two basic types of personality tests—projective tests and self-report inventories. After looking at some of the most commonly used tests in each category, we’ll evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each approach.

Projective Tests

LIKE SEEING THINGS IN THE CLOUDS

Spencer Grant/Photo Edit

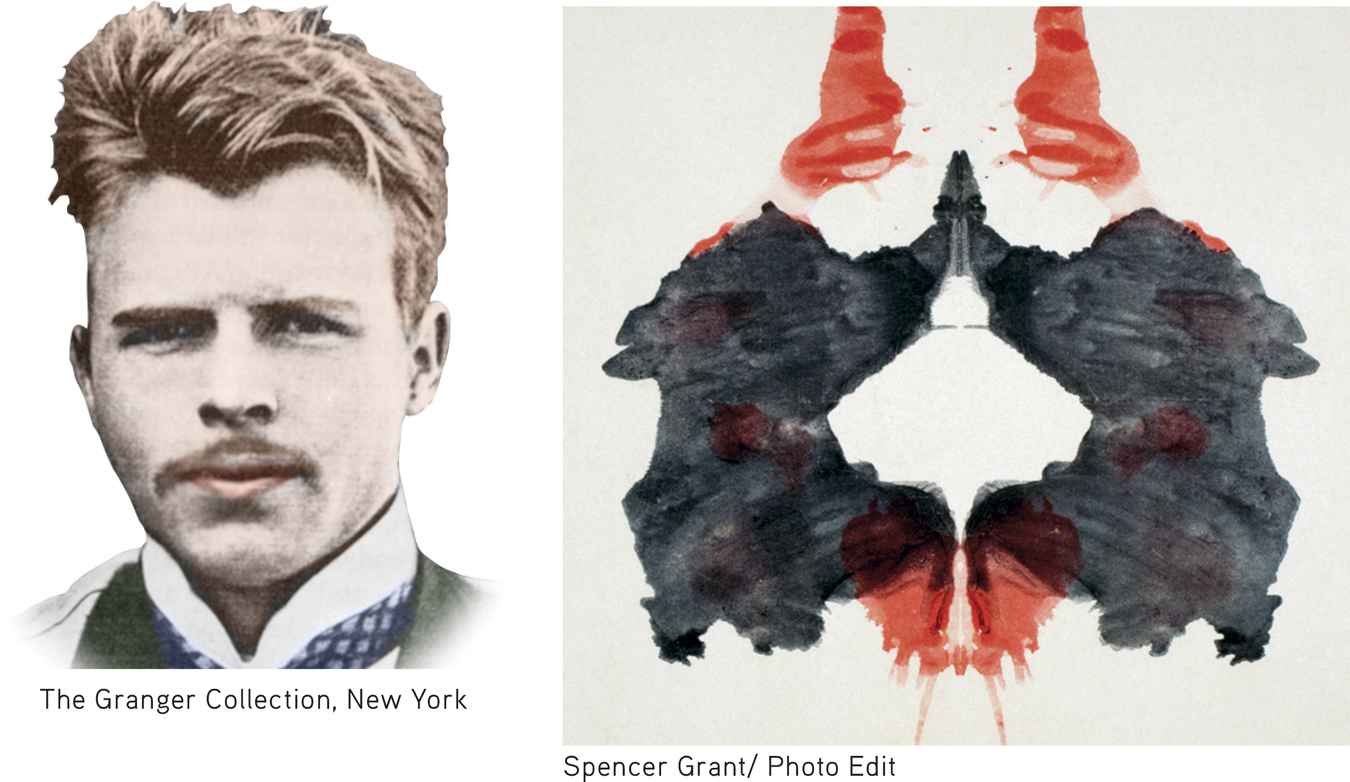

Projective tests developed out of psychoanalytic approaches to personality. In the most commonly used projective tests, a person is presented with a vague image, such as an inkblot or an ambiguous scene, then asked to describe what she “sees” in the image. The person’s response is thought to be a projection of her unconscious conflicts, motives, psychological defenses, and personality traits. Notice that this idea is related to the defense mechanism of projection, which was described in TABLE 11.1 earlier in the chapter. The first projective test was the famous Rorschach Inkblot Test, published by Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach in 1921 (Hertz, 1992).

projective test

A type of personality test that involves a person’s interpreting an ambiguous image; used to assess unconscious motives, conflicts, psychological defenses, and personality traits.

Rorschach Inkblot Test

A projective test using inkblots, developed by Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach in 1921.

The Rorschach test consists of 10 cards, 5 that show black-and-white inkblots and 5 that depict colored ink-blots. One card at a time, the person describes whatever he sees in the inkblot. The examiner records the person’s responses verbatim and also observes his behavior, gestures, and reactions.

Numerous scoring systems exist for the Rorschach. Interpretation is based on such criteria as whether the person reports seeing animate or inanimate objects, human or animal figures, and movement, and whether the person deals with the whole blot or just fragments of it (Exner, 2007; Exner & Erdberg, 2005).

SCIENCE VERSUS PSEUDOSCIENCE

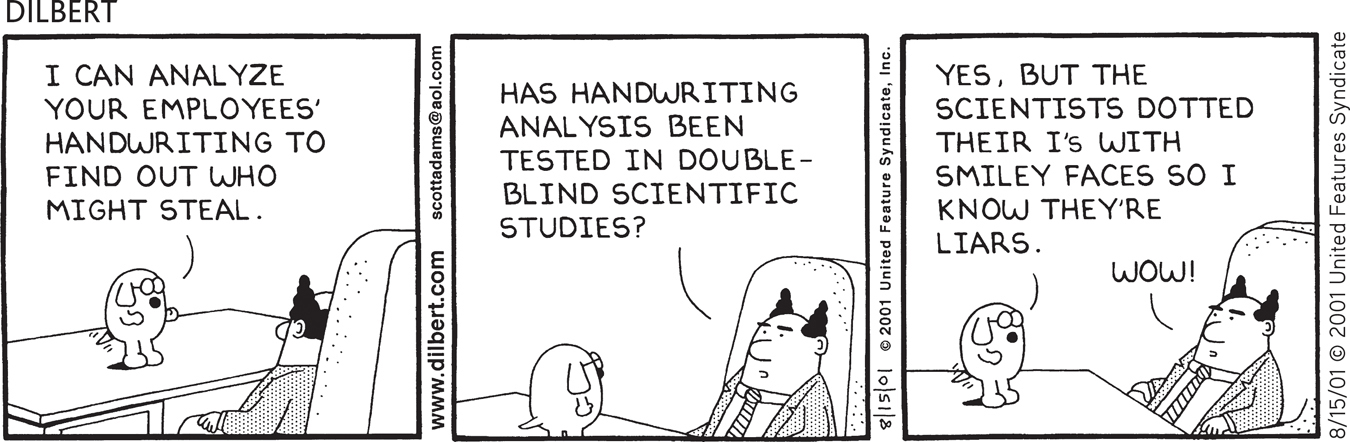

Graphology: The “Write” Way to Assess Personality?

Does the way that you shape your d’s, dot your i’s, and cross your t’s reveal your true inner nature? That’s the basic premise of graphology, a pseudoscience that claims that your handwriting reveals your temperament, personality traits, intelligence, and reasoning ability. If that weren’t enough, graphologists also claim that they can accurately evaluate a job applicant’s honesty, reliability, leadership potential, ability to work with others, and so forth (Beyerstein, 2007; Beyerstein & Beyerstein, 1992).

graphology

A pseudoscience that claims to assess personality, social, and occupational attributes based on a person’s distinctive handwriting, doodles, and drawing style.

Handwriting analysis is very popular throughout North America and Europe. In the United States alone, there are over 30 graphology societies, each promoting its own specific methods of analyzing handwriting (Beyerstein, 1996). Many different types of agencies and institutions use graphology. For example, the FBI and the U.S. State Department have consulted graphologists to assess the handwriting of people who mail death threats to government officials (Scanlon & Mauro, 1992).

Graphology is especially popular in the business world. Thousands of American companies, including Sears, U.S. Steel, and Bendix, have used graphology to assist in hiring new employees (Basil, 1991; Taylor & Sackheim, 1988). The use of graphology in hiring and promotions is even more widespread in Europe. According to one estimate, over 80 percent of European companies use graphology in personnel matters (Greasley, 2000; see Simner & Goffin, 2003).

When subjected to scientific evaluation, how does graphology fare? Consider a study by Anthony Edwards and Peter Armitage (1992) that investigated graphologists’ ability to distinguish among people in three different groups:

Successful versus unsuccessful secretaries

Successful business entrepreneurs versus librarians and bank clerks

Actors and actresses versus monks and nuns

In designing their study, Edwards and Armitage enlisted the help of leading graphologists and incorporated their suggestions into the study design. The graphologists preapproved the study’s format and indicated that they felt it was a fair test of graphology. The graphologists also predicted they would have a high degree of success in discriminating among the people in each group. One graphologist stated that the graphologists would have close to a 100 percent success rate. Remember that prediction.

The three groups—successful/unsuccessful secretaries, entrepreneurs/librarians, and actors/monks—represented a combined total of 170 participants. As requested by the graphologists, all participants indicated their age, sex, and hand preference. Each person also produced 20 lines of spontaneous handwriting on a neutral topic.

Four leading graphologists independently evaluated the handwriting samples. For each group, the graphologists tried to assign each handwriting sample to one category or the other. Two control measures were built into the study: (1) The handwriting samples were also analyzed by four ordinary people with no formal training in graphology or psychology; and (2) a typewritten transcript of the handwriting samples was evaluated by four psychologists. The psychologists made their evaluations on the basis of the content of the transcripts rather than on the handwriting itself.

In the accompanying table, you can see how well the graphologists fared as compared to the untrained evaluators and the psychologists. Clearly, the graphologists fell far short of the nearly perfect accuracy they predicted they would demonstrate. In fact, in one case, the untrained assessors actually outperformed the graphologists—they were slightly better at identifying successful versus unsuccessful secretaries.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that handwriting analysis provides insights into your personality and predicts occupational success?

Overall, the completely inexperienced judges achieved a success rate of 59 percent correct. The professional graphologists achieved a slightly better success rate of 65 percent. Obviously, this is not a great difference.

Hundreds of other studies have cast similar doubts on the ability of graphology to identify personality characteristics and to predict job performance from handwriting samples (Bangerter & others, 2009; Dazzi & Pedrabissi, 2009). In a global review of the evidence, psychologist Barry Beyerstein (1996) wrote, “Graphologists have unequivocally failed to demonstrate the validity or reliability of their art for predicting work performance, aptitudes, or personality. … If graphology cannot legitimately claim to be a scientific means of measuring human talents and leanings, what is it really? In short, it is a pseudoscience.”

| Group Assessed | Graphologists | Untrained Assessors | Psychologists |

|---|---|---|---|

| Good/bad secretaries | 67% | 70% | 56% |

| Entrepreneurs/librarians | 63% | 53% | 52% |

| Actors/monks | 67% | 58% | 53% |

| Overall success rate | 65% | 59% | 54% |

Lewis J. Merrim /Photo Researchers, Inc.

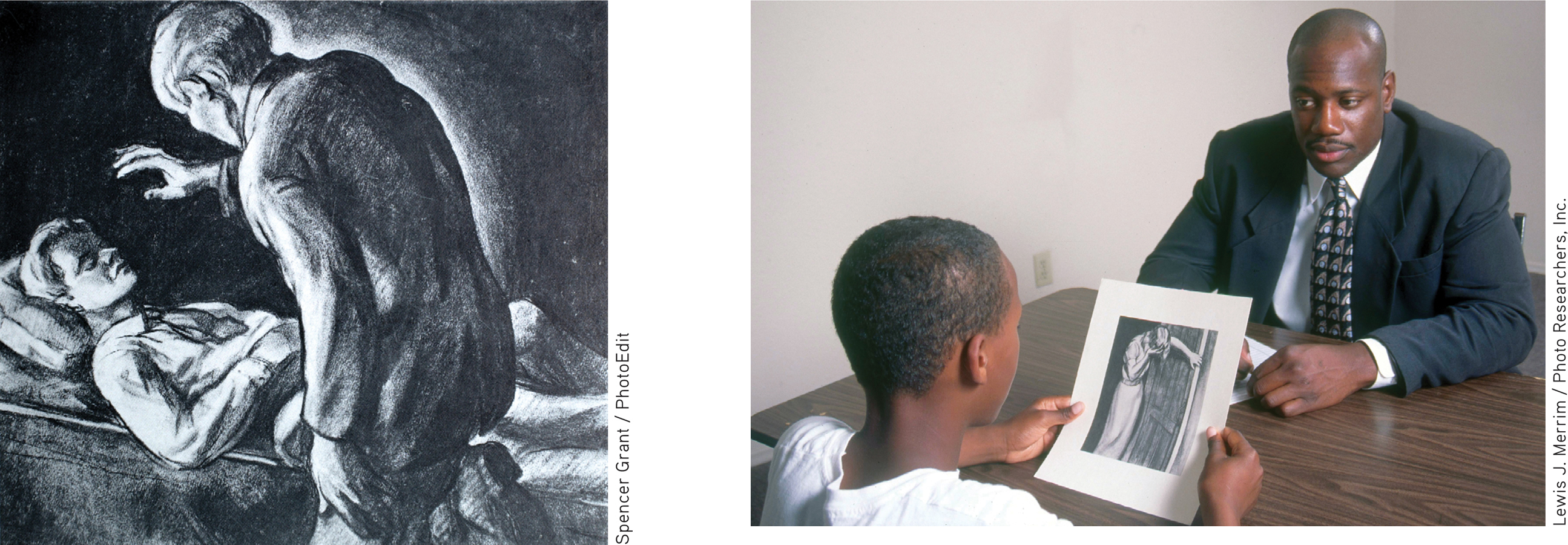

A more structured projective test is the Thematic Apperception Test, abbreviated TAT, which we discussed in Chapter 8. In the TAT, the person looks at a series of cards, each depicting an ambiguous scene. The person is asked to create a story about the scene, including what the characters are feeling and how the story turns out. The stories are scored for the motives, needs, anxieties, and conflicts of the main character and for how conflicts are resolved (Bellak, 1993; Langan-Fox & Grant, 2006; Moretti & Rossini, 2004). As with the Rorschach, interpreting the TAT involves the subjective judgment of the examiner.

Thematic Apperception Test (TAT)

A projective personality test, developed by Henry Murray and colleagues, that involves creating stories about ambiguous scenes.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF PROJECTIVE TESTS

Although sometimes used in research, projective tests are mainly used in counseling and psychotherapy. According to many clinicians, the primary strength of projective tests is that they provide a wealth of qualitative information about an individual’s psychological functioning, information that can be explored further in psychotherapy.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that projective tests, like the famous Rorschach inkblot test, accurately reveal personality traits and unconscious conflicts?

However, there are several drawbacks to projective tests. First, the testing situation or the examiner’s behavior can influence a person’s responses. Second, the scoring of projective tests is highly subjective, requiring the examiner to make numerous judgments about the person’s responses. Consequently, two examiners may test the same individual and arrive at different conclusions. Third, projective tests often fail to produce consistent results. If the same person takes a projective test on two separate occasions, very different results may be found. Finally, projective tests are poor at predicting future behavior.

The bottom line? Despite their widespread use, hundreds of studies of projective tests seriously question their validity—that the tests measure what they purport to measure—and their reliability—the consistency of test results (Garb & others, 2004; Weiner & Meyer, 2009). Nonetheless, projective tests remain very popular, especially among clinical psychologists (Butcher & Rouse, 1996; Leichtman, 2004).

Self-Report Inventories

DOES ANYONE HAVE AN ERASER?

Self-report inventories typically use a paper-and-pencil format and take a direct, structured approach to assessing personality. People answer specific questions or rate themselves on various dimensions of behavior or psychological functioning. Often called objective personality tests, self-report inventories contain items that have been shown by previous research to differentiate among people on a particular personality characteristic. Unlike projective tests, self-report inventories are objectively scored by comparing a person’s answers to standardized norms collected on large groups of people.

self-report inventory

A type of psychological test in which a person’s responses to standardized questions are compared to established norms.

The most widely used self-report inventory is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) (Butcher, 2010). First published in the 1940s and revised in the 1980s, the current version is referred to as the MMPI-2. The MMPI consists of over 500 statements. The person responds to each statement with “True,” “False,” or “Cannot say.” Topics include social, political, religious, and sexual attitudes; physical and psychological health; interpersonal relationships; and abnormal thoughts and behaviors (Delman & others, 2008; Graham, 1993; McDermut & Zimmerman, 2008). Items similar to those used in the MMPI are shown in TABLE 11.6.

Simulated MMPI-2 Items

| Most people will use somewhat unfair means to gain profit or an advantage rather than lose it. I am often very tense on the job. The things that run through my head sometimes are horrible. Sometimes there is a feeling like something is pressing in on my head. Sometimes I think so fast I can’t keep up. I am worried about sex. I believe I am being plotted against. I wish I could do over some of the things I have done. |

| Source: MMPI-2®. |

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)

A self-report inventory that assesses personality characteristics and psychological disorders; used to assess both normal and disturbed populations.

The MMPI is widely used by clinical psychologists and psychiatrists to assess patients. It is also used to evaluate the mental health of candidates for such occupations as police officers, doctors, nurses, and professional pilots. What keeps people from simply answering items in a way that makes them look psychologically healthy? Like many other self-report inventories, the MMPI has special scales to detect whether a person is answering honestly and consistently (Butcher, 2010; Pope & others, 2006). For example, if someone responds “True” to items such as “I never put off until tomorrow what I should do today” and “I always pick up after myself,” it’s probably a safe bet that she is inadvertently or intentionally distorting her other responses.

The MMPI was originally designed to assess mental health and detect psychological symptoms. In contrast, the California Psychological Inventory and the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire are personality inventories that were designed to assess normal populations (Boer & others, 2008; Megargee, 2009). Of the over 400 true–

California Psychological Inventory (CPI)

A self-report inventory that assesses personality characteristics in normal populations.

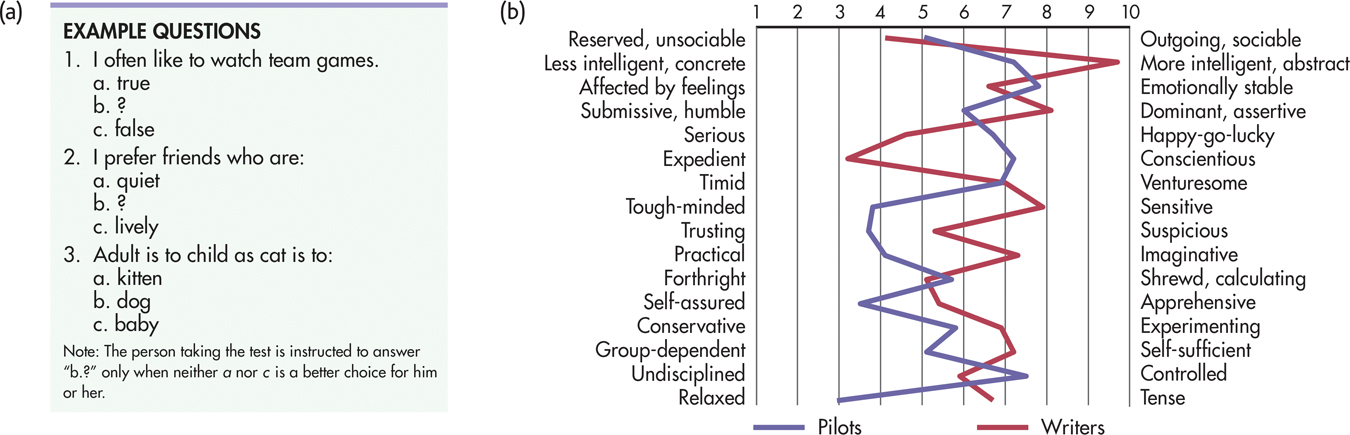

The Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF) was originally developed by Raymond Cattell and is based on his trait theory. The 16PF uses a forced-choice format in which the person must respond to each item by choosing one of three alternatives. Just as the test’s name implies, the results generate a profile on Cattell’s 16 personality factors. Each personality factor is represented as a range, with a person’s score falling somewhere along the continuum between the two extremes (see FIGURE 11.4). The 16PF is widely used for career counseling, marital counseling, and evaluating employees and executives (H. E. P. Cattell & Mead, 2008; Clark & Blackwell, 2007).

Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF)

A self-report inventory developed by Raymond Cattell that generates a personality profile with ratings on 16 trait dimensions.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that it’s easy to fake the results of personality tests?

Another widely used personality test is the Myers–

The notion of personality types is fundamentally different from personality traits. According to trait theory, people display traits, such as introversion/extraversion, to varying degrees. If you took the 16PF or the CPI, your score would place you somewhere along a continuum from low (very introverted) to high (very extraverted). However, most people would fall in the middle or average range on this trait dimension. But according to type theory, a person is either an extrovert or an introvert—that is, one of two distinct categories that don’t overlap (Arnau & others, 2003; Wilde, 2011).

The MBTI arrives at personality type by measuring a person’s preferred way of dealing with information, making decisions, and interacting with others. There are four basic categories of these preferences, which are assumed to be dichotomies—that is, opposite pairs. These dichotomies are: Extraversion/Introversion; Sensing/Intuition; Thinking/Feeling; and Perceiving/Judging.

There are 16 possible combinations of scores on these four dichotomies. Each combination is considered to be a distinct personality type. An individual personality type is described by the initials that correspond to the person’s preferences as reflected in her MBTI score. For example, an ISFP combination would be a person who is introverted, sensing, feeling, and perceiving, while an ESTJ would be a person who is extroverted, sensing, thinking, and judging.

Despite the MBTI’s widespread use in business, counseling, and career guidance settings, research has pointed to several problems with the MBTI. One problem is reliability—people can receive different MBTI results on different test-taking occasions. Equally significant is the problem of validity. For example, research does not support the claim of a relationship between MBTI personality types and occupational success (Pittenger, 2005). More troubling is the lack of evidence supporting the existence of 16 distinctly different personality types (Hunsley & others, 2003). Thus, most researchers in the field of psychological testing advise that caution be exercised in interpreting MBTI results, especially in applying them to vocational choices or predictions of occupational success (see Pittenger, 2005).

Think Like a SCIENTIST

Can an assessment of your personality predict job success? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about Employment-Related Personality Tests.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF SELF-REPORT INVENTORIES

The two most important strengths of self-report inventories are their standardization and their use of established norms (see Chapter 7). Each person receives the same instructions and responds to the same items. The results of self-report inventories are objectively scored and compared to norms established by previous research. In fact, the MMPI, the CPI, and the 16PF can all be scored by computer.

As a general rule, the reliability and validity of self-report inventories are far greater than those of projective tests. Literally thousands of studies have demonstrated that the MMPI, the CPI, and the 16PF provide accurate, consistent results that can be used to generally predict behavior (Anastasi & Urbina, 1997).

However, self-report inventories also have their weaknesses. First, despite the inclusion of items designed to detect deliberate deception, there is considerable evidence that people can still successfully fake responses and answer in socially desirable ways (Anastasi & Urbina, 1997; Holden, 2008). Second, some people are prone to responding in a set way. They may consistently pick the first alternative or answer “True” whether the item is true for them or not. And some tests, such as the MMPI and CPI, include hundreds of items. Taking these tests can become quite tedious, and people may lose interest in carefully choosing the most appropriate response.

Third, people are not always accurate judges of their own behavior, attitudes, or attributes. And some people defensively deny their true feelings, needs, and attitudes, even to themselves (Cousineau & Shedler, 2006; Shedler & others, 1993). For example, a person might indicate that she enjoys parties, even though she actually avoids social gatherings whenever possible.

To sum up, personality tests are generally useful strategies that can provide insights about the psychological makeup of people. But no personality test, by itself, is likely to provide a definitive description of a given individual. In practice, psychologists and other mental health professionals usually combine personality test results with behavioral observations and background information, including interviews with family members, co-workers, or other significant people in the person’s life.

CONCEPT REVIEW 11.4

Trait Theories and Personality Assessment

Select the correct answer.

Question 11.20

Trait theories focus on:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.21

Surface traits are to source traits as:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.22

After conducting research on personality traits for many years, Professor Torres concludes that traits can be described in terms of five basic factors. Professor Torres agrees with the trait model proposed by:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.23

Imagine that a researcher has just discovered that the trait of “industriousness” is strongly influenced by genetics. If this were the case, which of the following pairs will be MOST alike on this trait?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.24

Dana took the same personality test twice within three months. She obtained very different results each time. Which test did she most likely take?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 11.25

A key strength of the MMPI and the 16PF is:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Test your understanding of Assessing Personality with

.

.

Closing Thoughts

Over the course of this chapter, you’ve encountered firsthand some of the most influential contributors to modern psychological thought. As you’ll see in Chapter 15, the major personality perspectives provide the basis for many forms of psychotherapy. Clearly, the psychoanalytic, humanistic, social cognitive, and trait perspectives each provide a fundamentally different way of conceptualizing personality. That each perspective has strengths and limitations underscores the point that no single perspective can explain all aspects of human personality. Indeed, no one personality theory could explain why Kenneth and Julian were so different. And, given the complex factors involved in human personality, it’s doubtful that any single theory ever will capture the essence of human personality in its entirety. Even so, each perspective has made important and lasting contributions to the understanding of human personality.