12.8 Altruism and Aggression

HELPING AND HURTING BEHAVIOR

KEY THEME

Prosocial behavior describes any behavior that helps another person, including altruistic acts. Aggression describes behavior that is intended to harm another person.

KEY QUESTIONS

What factors increase the likelihood that people will help a stranger?

What factors decrease the likelihood that people will help a stranger?

How can the lack of bystander response in the Genovese murder case be explained in light of psychological research on helping behavior?

What factors increase the likelihood that people will harm another person?

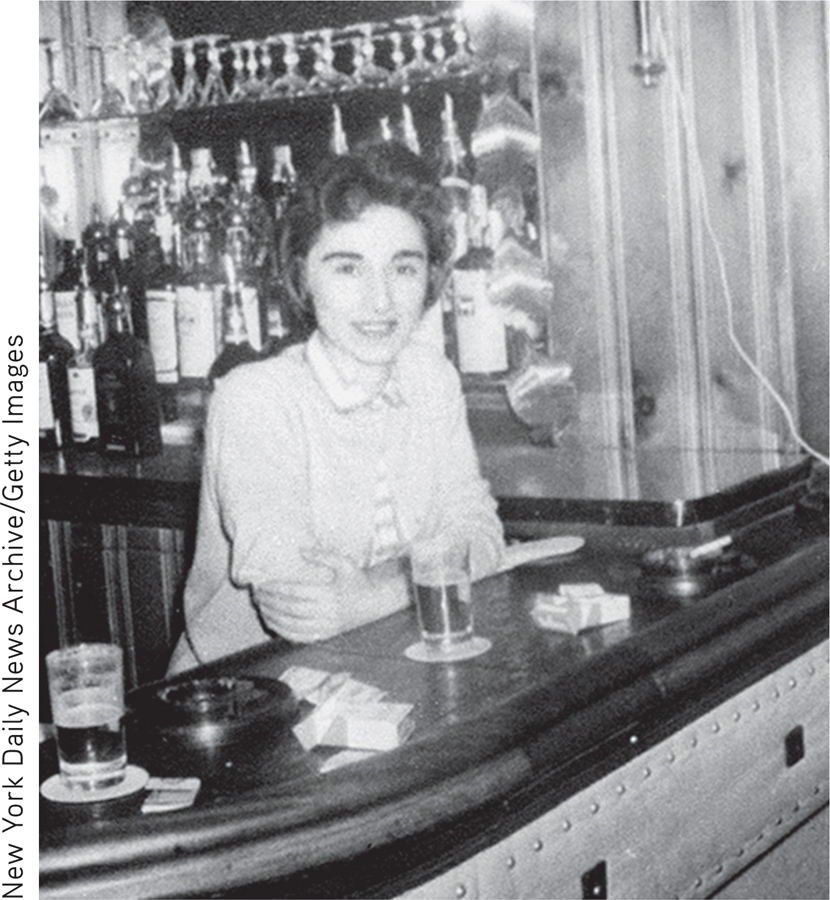

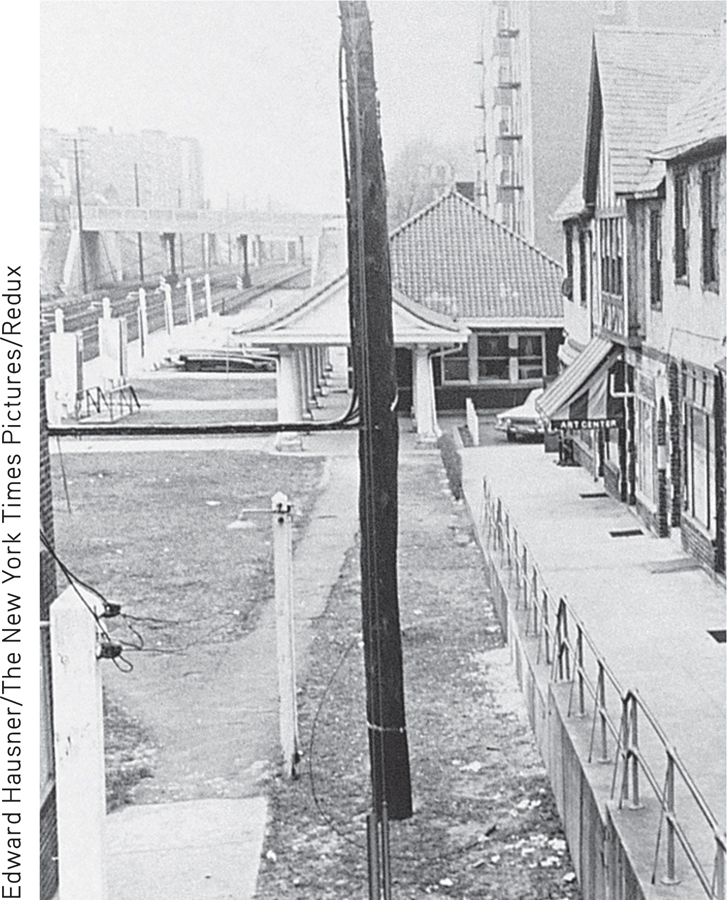

It was about 3:20 a.m. on Friday, March 13, 1964, when 28-year-old Kitty Genovese returned home from her job managing a bar. Like other residents in her middle-class New York City neighborhood, she parked her car at an adjacent railroad station. Her apartment entrance was only 100 feet away.

As she got out of her car, she noticed a man at the end of the parking lot. When the man moved in her direction, she began walking toward a nearby police call box, which was under a streetlight in front of a bookstore. On the opposite side of the street was a 10-story apartment building. As she neared the streetlight, the man grabbed her and she screamed. Across the street, lights went on in the apartment building. “Oh, my God! He stabbed me! Please help me! Please help me!” she screamed.

“Let that girl alone!” a man yelled from one of the upper apartment windows. The attacker looked up, then walked off, leaving Kitty on the ground, bleeding. The street became quiet. Minutes passed. One by one, lights went off. Struggling to her feet, Kitty made her way toward her apartment. As she rounded the corner of the building moments later, her assailant returned, stabbing her again. “I’m dying! I’m dying!” she screamed.

Again, lights went on. Windows opened and people looked out. This time, the assailant got into his car and drove off. It was now 3:35 a.m. Fifteen minutes had passed since Kitty’s first screams for help. A New York City bus passed by. Staggering, then crawling, Kitty moved toward the entrance of her apartment. She never made it. Her attacker returned, searching the apartment entrance doors. At the second apartment entrance, he found her, slumped at the foot of the steps. This time, he stabbed her to death.

It was 3:50 a.m. when someone first called the police. The police took just two minutes to arrive at the scene. About half an hour later, an ambulance carried Kitty Genovese’s body away. Only then did people come out of their apartments to talk to the police.

Over the next two weeks, police investigators learned that a total of 38 people had witnessed Kitty’s murder—a murder that involved three separate attacks over a period of about 30 minutes. Why didn’t anyone try to help her? Or call the police when she first screamed for help?

When The New York Times interviewed various experts, they seemed baffled, although one expert said it was a “typical” reaction (Mohr, 1964). If there was a common theme in their explanations, it seemed to be “apathy.” The occurrence was simply representative of the alienation and depersonalization of life in a big city, people said (see Rosenthal, 1964a, 1964b).

Not everyone bought this pat explanation. In the first place, it wasn’t true. As social psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley (1970) later pointed out in their landmark book, The Unresponsive Bystander: Why Doesn’t He Help?:

People often help others, even at great personal risk to themselves. For every “apathy” story, one of outright heroism could be cited…. It is a mistake to get trapped by the wave of publicity and discussion surrounding incidents in which help was not forthcoming into believing that help never comes. People sometimes help and sometimes don’t. What determines when help will be given?

That’s the critical question, of course. When do people help others? And why do people help others?

When we help another person with no expectation of personal benefit, we’re displaying altruism (Batson & others, 2011). An altruistic act is fundamentally selfless—the individual is motivated purely by the desire to help someone in need. Everyday life is filled with little acts of altruistic kindness, such as Fern giving the “homeless” man a handful of quarters or the stranger who thoughtfully holds a door open for you as you juggle an armful of packages.

altruism

Helping another person with no expectation of personal reward or benefit.

Altruistic actions fall under the broader heading of prosocial behavior, which describes any behavior that helps another person, whatever the underlying motive. Note that prosocial behaviors are not necessarily altruistic. Sometimes we help others out of guilt. And, sometimes we help others in order to gain something, such as recognition, rewards, increased self-esteem, or having the favor returned (Batson & others, 2011).

prosocial behavior

Any behavior that helps another, whether the underlying motive is self-serving or selfless.

Factors That Increase the Likelihood of Bystanders Helping

Kitty Genovese’s death triggered hundreds of investigations into the conditions under which people will help others (Dovidio, 1984; Dovidio & others, 2006). Those studies began in the 1960s with the pioneering efforts of Bibb Latané and John Darley, who conducted a series of ingenious experiments in which it appears that help is needed. For example, in one study, participants believed they were overhearing an epileptic seizure (Darley & Latané, 1968). In another study, participants were in a room that started to fill with smoke (Latané & Darley, 1968). Based on these studies, Latané and Darley concluded that people must pass through three stages before they offer help. First, they must notice an emergency situation. Second, they must interpret it as a situation that actually requires help. Third, they must decide that it is their responsibility to offer help (Latané & Darley, 1968).

Other researchers joined the effort to understand what factors influence a person’s decision to help another (see Dovidio & others, 2006; Fischer & others, 2011). Some of the most significant factors that increase the likelihood of helping include:

The “feel good, do good” effect. People who feel good, successful, happy, or fortunate are more likely to decide to help others (see Forgas & others, 2008; C. Miller, 2009). Those good feelings can be due to virtually any positive event, such as receiving a gift, succeeding at a task, or even just enjoying a warm, sunny day.

Feeling guilty. We tend to be more helpful when we’re feeling guilty. For example, after telling a lie or inadvertently causing an accident, people were more likely to decide to help others (Basil & others, 2006; de Hooge & others, 2011). In general, people who are prone to guilt are more likely to act ethically and honestly (Cohen & others, 2012).

Seeing others who are willing to help. Whether it’s donating blood, helping a stranded motorist change a flat tire, or dropping money in the Salvation Army kettle during the holiday season, we’re more likely to decide to help if we observe others do the same (Fischer & others, 2011).

Perceiving the other person as deserving help. We’re more likely to decide to help people who are in need of help through no fault of their own. For example, people are twice as likely to give some change to a stranger if they believe the stranger’s wallet has been stolen than if they believe the stranger has simply spent all his money (Burn, 2009; Laner & others, 2001; Latané & Darley, 1970). Similarly, people are more likely to support welfare programs if they believe that the welfare recipients are actively trying to find a job (Petersen & others, 2012).

Knowing how to help. Research has confirmed that knowing what to do and being physically capable of helping contributes greatly to the decision to help someone else (Fischer & others, 2011; Steg & de Groot, 2010). In line with this, some colleges, including Yale University and the University of Arizona, have implemented bystander training to give students skills to intervene, for example, to prevent a sexual assault (Hua, 2013; University of Arizona, 2013).

A personalized relationship. When people have any sort of personal relationship with another person, they’re more likely to decide to help that person. Even minimal social interaction with each other, such as making eye contact, engaging in small talk, or smiling, increases the likelihood that one person will help the other (Solomon & others, 1981; Vrugt & Vet, 2009).

A dangerous situation. People also are more likely to decide to help in dangerous situations—those that are clearly an emergency, those when the perpetrator is present, and those that present a physical risk to the helper (Fischer & others, 2011). This might seem surprising, but it may be that these are situations in which it is clear that help is needed.

Factors That Decrease the Likelihood of Bystanders Helping

It’s equally important to consider influences that decrease the likelihood of helping behavior. As we look at some of the key findings, we’ll also note how each factor might have played a role in the death of Kitty Genovese.

The presence of other people. In general, people are much more likely to decide to help when they are alone (Fischer & others, 2011; Latané & Nida, 1981). If other people are present or imagined, helping behavior declines—a phenomenon called the bystander effect.

bystander effect

A phenomenon in which the greater the number of people present, the less likely each individual is to help someone in distress.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that people are more likely to help others if they are the only ones available to help?

There seem to be two major reasons for the bystander effect. First, the presence of other people creates a diffusion of responsibility. The responsibility to intervene is shared (or diffused) among all the onlookers. Because no one person feels all the pressure to respond, each bystander becomes less likely to help.

diffusion of responsibility

A phenomenon in which the presence of other people makes it less likely that any individual will help someone in distress because the obligation to intervene is shared among all the onlookers.

Ironically, the sheer number of bystanders seemed to be the most significant factor working against Kitty Genovese. Remember that when she first screamed, a man yelled down, “Let that girl alone!” With that, each observer instantly knew that he or she was not the only one watching the events on the street below. Hence, no single individual felt the full responsibility to help.

Second, the bystander effect seems to occur because each of us is motivated to some extent by the desire to behave in a socially acceptable way (normative social influence) and to appear correct (informational social influence). In the case of Kitty Genovese, the lack of intervention by any of the witnesses may have signaled the others that intervention was not appropriate, wanted, or needed.

Being in a big city or a very small town. Kitty Genovese was attacked late at night in one of the biggest cities in the world. Research by Robert Levine and his colleagues (2008) confirmed that people are less likely to decide to help strangers in big cities, but other aspects of city life also affect helping. Crowding, economic status, and even how fast people are walking can influence whether a person is helped or not. On the other hand, people are also less likely to help a stranger in towns with populations under 5,000 (Steblay, 1987).

Vague or ambiguous situations. When situations are ambiguous and people are not certain that help is needed, they’re less likely to decide to offer help (Solomon & others, 1978). The ambiguity of the situation may also have worked against Kitty Genovese. The people in the apartment building saw a man and a woman struggling on the street below but had no way of knowing whether the two were acquainted. “We thought it was a lovers’ quarrel,” some of the witnesses later said (Gansberg, 1964). Researchers have found that people are especially reluctant to intervene when the situation appears to be a domestic dispute or a “lovers’ quarrel,” because they are not certain that assistance is wanted (Gracia & others, 2009).

When the personal costs for helping outweigh the benefits. As a general rule, we tend to weigh the costs as well as the benefits of helping in deciding whether to act. If the potential costs outweigh the benefits, it’s less likely that people will help (Fischer & others, 2006, 2011). The witnesses in the Genovese case may have felt that the benefits of helping Genovese were outweighed by the potential hassles and danger of becoming involved in the situation.

On a small yet universal scale, the murder of Kitty Genovese dramatically underscores the power of situational and social influences to affect our behavior. Although social psychological research has provided insights about the factors that influenced the behavior of those who witnessed the Genovese murder, it should not be construed as a justification for the inaction of the bystanders. After all, Kitty Genovese’s death probably could have been prevented by a single phone call. If we understand the factors that decrease helping behavior, we can recognize and overcome those obstacles when we encounter someone who needs assistance. If you had been Kitty Genovese—or if Kitty Genovese had been your sister, friend, or classmate—how would you have hoped other people would react?

Aggression

HURTING BEHAVIOR

The flip side of helping behavior is hurting behavior, or aggression—any verbal or physical behavior intended to cause harm to other people. To be classified as aggression, the aggressor must believe that their behavior is harmful to the other person, and that other person must not wish to be harmed (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). A child who hits her little brother, a mugger who threatens his victim, a boss who screams at her subordinates, or a terrorist who fires shots in a crowded mall—all are engaged in acts of aggression. But the doctor who knowingly inflicts pain while setting a broken arm is not.

aggression

Verbal or physical behavior intended to cause harm to other people.

Have you ever wondered about the wide variation in aggressive tendencies? Why does one friend threaten a fistfight when provoked, while another calmly walks away? Like helping behavior, hurting behavior is driven by a range of factors—biological, psychological, and sociocultural.

THE INFLUENCE OF BIOLOGY ON AGGRESSION

Researchers have long thought that our tendency to behave aggressively has a biological component. Biological theories of aggression include genetic, structural, and biochemical explanations.

The Influence of Genes and Brain StructureWhen someone behaves aggressively, how do we know if that is driven, even in part, by inborn personality characteristics? There have been a number of studies that tried to separate the effects of genes and environmental influences in rates of aggression. For example, one study found that identical twins had similar aggressive tendencies whether or not they were raised together. Because twins share 100% of their genes, this finding indicates a strong genetic influence on aggressive behavior (Bouchard & others, 1990; Segal, 2012). Two meta-analyses that explored studies on heredity and aggression concluded that genetics played a significant role in people’s levels of aggressiveness (Ferguson, 2010; Miles & Carey, 1997).

The presence of behaviors that appear to be driven, at least in part, by genetics leads to questions about whether these behaviors have an evolutionary basis. That is, are there adaptive benefits to having a genetic predisposition toward aggression, at least in certain contexts? Evolutionary theorists say yes (Ferguson & Beaver, 2009). Aggression, they assert, can help people to acquire or secure resources for themselves and for those who share their genes (Buss & Duntley, 2006).

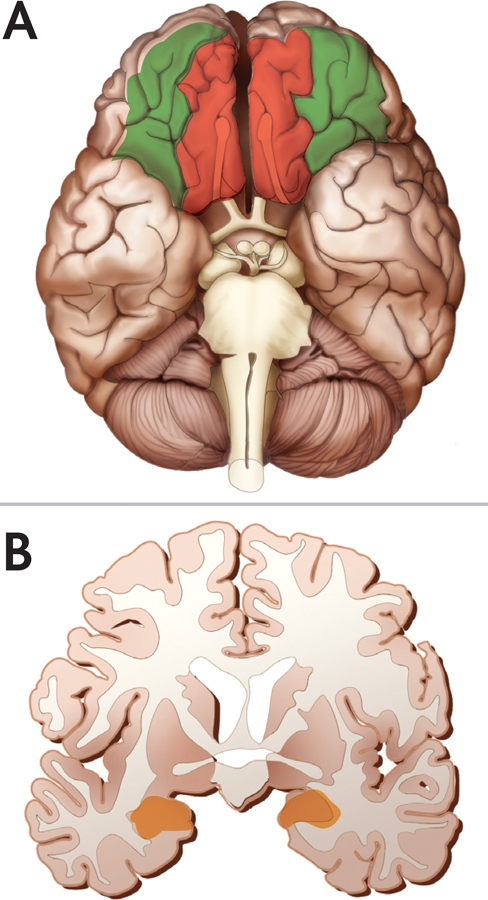

Another biological explanation for aggression points to differences in the parts of the brain that regulate emotion, including the amygdala, the prefrontal cortex, and the limbic system (Bobes & others, 2013; Davidson & others, 2000; Meyer-Lindenberg & others, 2006). For example, researchers have observed differences in the prefrontal cortex of people who are prone to aggressive and angry outbursts (Best & others, 2002).

Biochemical InfluencesBiochemical influences on aggression include the hormone testosterone and alcohol abuse. For example, Irene van Bokhoven and her colleagues (2006) followed 96 boys from kindergarten through age 21. They found that boys who had higher levels of testosterone over this period were more likely to have criminal records as adults. This tendency is not limited to men. Both male and female college students who had committed acts of violence or engaged in drug use were found to have higher rates of testosterone (Banks & Dabbs, 1996). And a link between testosterone and aggression has been found among female prisoners (Dabbs & Hargrove, 1997).

However, it’s important not to overstate the link between testosterone and aggression. In a meta-analysis of 45 studies, Angela Book and her colleagues (2001) found only a weak relationship between the two. Further, some researchers point out that high testosterone can also have positive effects. For example, it may be linked to good negotiation and leadership skills (Yildirim & Derksen, 2012).

Although most people who consume alcohol are not violent, the rate of violence is higher among those under the influence of alcohol than among those who have not consumed alcohol (Duke & others, 2011). This effect has been established in both laboratory and everyday settings (Chermack & Taylor, 1995; Exum, 2006; Graham & others, 2006). One research team bravely spent over 1,000 nights in over 100 bars in Toronto, Canada and logged more than 1,000 violent incidents. As the crowd became more intoxicated, aggressive incidents were more likely to occur. And, the aggressive person’s level of intoxication was generally related to the severity of the violent act (Graham & others, 2006).

PSYCHOLOGICAL INFLUENCES ON AGGRESSION

While it’s clear that there are biological influences on aggression, there also are psychological influences. For example, a great deal of aggressive behavior is learned. In addition, there are situational factors that can increase people’s tendency to be aggressive.

LearningPeople who are violent are often mimicking behavior they have seen, a form of observational learning. For example, in Chapter 5, you read about Albert Bandura’s classic Bobo Doll experiments in which children learned to behave aggressively toward a large balloon doll by watching a brief video in which an adult did the same. Exposure to violence may also lead to aggression over the longer term. Researchers have found that both women and men exposed to violence in their families while growing up were more likely to abuse their partners and their children as adults (Heyman & Slep, 2002). But a higher likelihood is not a guarantee that the family pattern of violence will be repeated. In fact, most people who were exposed to violence as children do not grow up to be abusers themselves.

There also is evidence that exposure to violence in the media—whether in a film, a video game, or music lyrics—might increase the likelihood that someone will behave aggressively, perhaps imitating the violence they viewed. In the Critical Thinking box “Does Exposure to Media Violence Cause Aggressive Behavior” in Chapter 5, you read about the evidence that viewing media violence is related to aggressive behavior (see Bushman & others, 2009). Viewing pornography, especially pornography depicting sexual violence, also has been linked to increased aggressive attitudes toward women (Hald & others, 2009). Although there is a strong link, it’s important to note that much of the research connecting media violence to actual aggressive behavior is correlational. Remember from Chapter 1 that correlational studies cannot tell us whether one variable, such as pornography, causes another, such as aggression. The research that is experimental and could show causal links is primarily in artificial situations (Ferguson & Kilbourn, 2009).

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that there is no link between aggression and playing violent video games?

Other forms of violent media, like violent video games, also have been linked to increased aggression. For example, one study followed more than 1,000 boys and girls throughout their high school years, and found that students who played violent video games throughout this time showed increases in aggressive behavior over the four years of the study (Willoughby & others, 2013). Listening to violent music lyrics—from heavy metal, rap, and rock songs—led participants in one study to be more aggressive. Compared with participants who listened to the same music without lyrics, they doled out larger amounts of a painful hot sauce for another (fictional) participant to consume (Brummert Lennings & Warburton, 2011). Because this was an experiment, we can safely conclude that listening to the violent lyrics caused the higher levels of aggressive behavior.

FrustrationAggression can be learned, but it can also be driven by situational factors that are annoying or frustrating. For example, researchers have identified high temperatures as a source for frustration-linked aggression (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). Researchers found that violence in Minneapolis increased as nighttime temperatures increased (Bushman & others, 2005). Even exposure to words associated with hotter temperatures—sunburn or sweats, for example—leads to increased hostility as compared with neutral or colder words (DeWall & Bushman, 2009). Temperature is also linked to violence on a global scale. Researchers have estimated substantial increases in violence between individuals as climate change leads to warmer temperatures globally, and even larger increases in violence between groups (Hsiang & others, 2013).

When frustrated by a stressful situation or an annoying person, people can react aggressively (Anderson & Buschman, 2002). Jodi Whitaker and her colleagues (2013) conducted an experiment in which they created a situation that would be incredibly frustrating to their student participants. The students were invited to take an extremely difficult history test that could earn them desirable snacks for a top performance. Some students were then “mistakenly” given access to the answers—but were frustrated by having the answers, and the chance to cheat, quickly taken away. After taking the test, students were asked to rate a series of violent and nonviolent video games. Students who were frustrated rated their desire to play violent video games higher than students who never had a chance to cheat or who never had their chance to cheat taken away.

When’s the last time you got really frustrated or angry? If you drive, it might have been behind the wheel. About one third of us admit to having been the aggressor in a road rage situation, and that’s particularly true of younger drivers and male drivers (Smart & others, 2003). Road rage results from a number of factors, especially frustration—the frustration that results when we perceive inappropriate or reckless driving behavior, when there is heavy traffic, or when we’re running late (Wickens & others, 2013). These factors are even more frustrating—and even more likely to lead to aggression—when we’re already stressed out for other reasons (Wickens & others, 2013).

GENDER, CULTURE, AND AGGRESSION

Quick—which gender do you think is more likely to engage in aggressive behavior? In this case, the stereotype that males are the more aggressive gender is true, on average. (But just on average. As with every psychology finding, there are lots of exceptions.) Psychologist John Archer (2004) conducted a meta-analysis of aggression in real-world settings. He concluded that “Direct, especially physical, aggression was more common in males than females at all ages sampled, was consistent across cultures, and occurred from early childhood on, showing a peak between 20 and 30 years.” Research suggests, however, that girls and women are just as aggressive as boys in indirect aggression, which refers to aggression related to interactions, such as gossiping and spreading rumors (Archer & Coyne, 2005).

Why is it the case that men are more likely than women to behave in physically aggressive ways? There may be biological reasons. Evolutionary theorists suggest that the gender difference is due to the fact that men are more likely to reproduce if they have access to desirable mating partners, something that is more likely for men with resources—which can be acquired through aggression (Buss & Duntley, 2006). In addition, men are more likely to use aggression in the context of mating. For example, in an experiment, men who thought about sexual topics were more likely to behave aggressively than men who thought about topics related to happiness (Ainsworth & Maner, 2012).

But there also are environmental explanations. The ways in which girls and boys exhibit aggression are influenced by the reactions of others. Children learn aggression-related scripts—or guides for how they should act—by responding to input from peers and teachers, parents and other family members, and the media (Ostrov & Godleski, 2010).

Cultural factors also influence aggressive behavior and attitudes. Researchers have found that there are regional and national differences in certain types of aggression based on the concept of a culture of honor (Vandello & others, 2008). A culture of honor is one in which actions perceived as damaging your reputation must be addressed (Vandello & Cohen, 2004). In some countries, such as Turkey, the culture of honor is focused on offenses against one’s family (Cihangir, 2013; van Osch & others, 2013). In the Americas, especially the southern United States and Latin America, the culture of violence tends to be based on masculine honor. Psychologist Joseph Vandello and his colleagues (2008) describe masculine honor as having “an emphasis on masculinity and male toughness.” In such cultures, violence that is seen as helping a man restore his reputation is more acceptable. For example, if a man is mocked at a sporting event, a violent response might be seen as reasonable or even admirable (Vandello & Cohen, 2003). Masculine honor culture, although usually regional, can also be contextual. Some researchers have observed an aggression-inducing culture of masculine honor in North American bars (Graham & Wells, 2003).

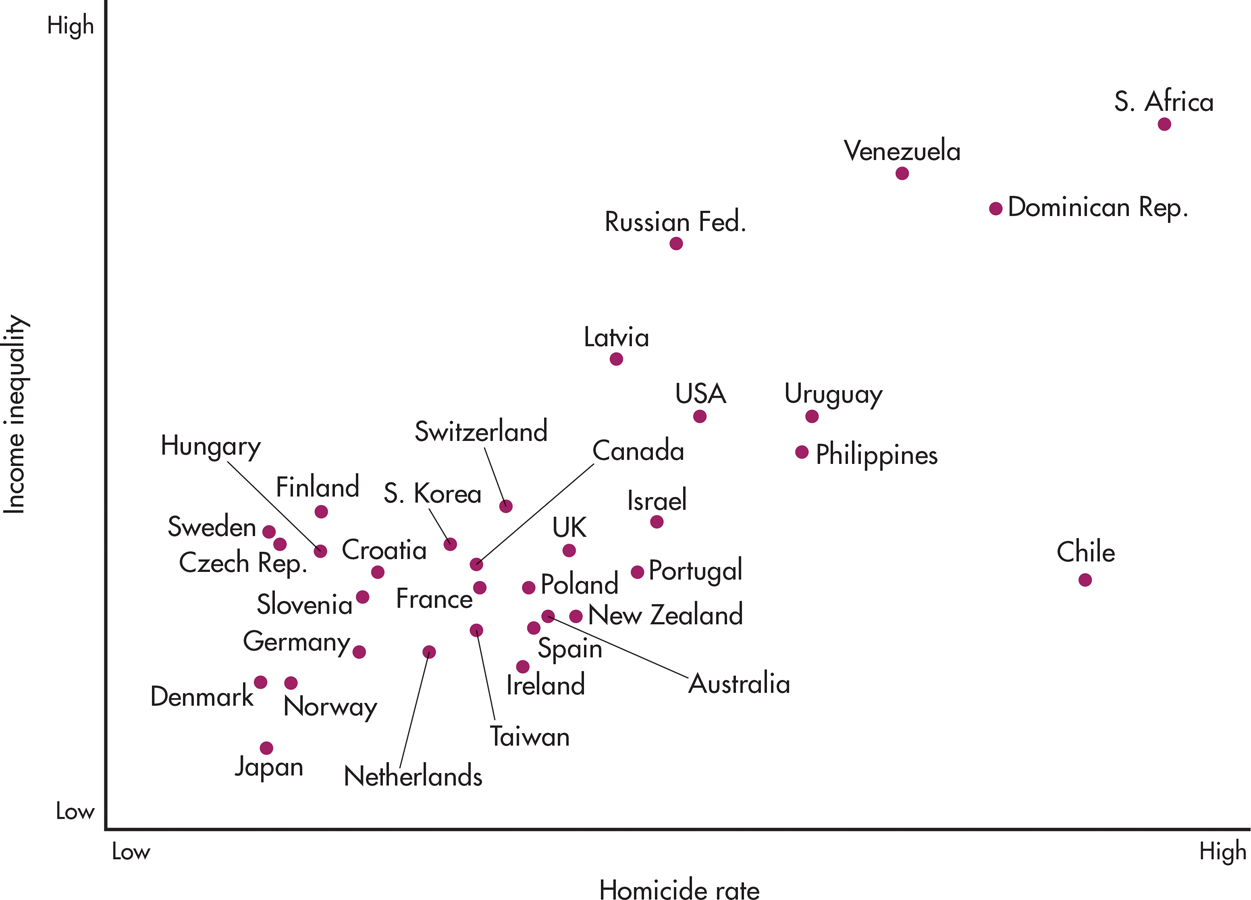

Cultures with significant income inequality also have higher rates of aggression. Researchers have identified a strong link between income inequality and violence, particularly murder (Nivette, 2011; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). For example, a study of 33 countries found a very high correlation of 0.80 between the level of income inequality in a country and the homicide rate (Elgar & Aitken, 2010; see FIGURE 12.5). From Chapter 1, you may remember that the highest possible correlation is 1.00, indicating that two variables are perfectly related. A correlation of 0.80 is close to the highest you would see in social science research. Just the fact that this important cultural element is so tightly bound with extreme violence is an indication that sociocultural factors, in addition to biological and psychological factors, are important predictors of violence.

CONCEPT REVIEW 12.3

Factors Influencing Conformity, Obedience, Helping Behavior, and Hurting Behavior

Select the correct answer.

Question 12.1

1. Although Matt prefers to dress casually, he wears a button-down shirt and tie to work because he wants to fit in with the other sales representatives. Matt’s behavior is best explained as a matter of:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 12.2

2. According to Stanley Milgram, which of the following statements helps explain the teachers’ willingness to deliver progressively stronger shocks to the learner in the original obedience experiment?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 12.3

3. Conformity and obedience research suggests that:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 12.4

4. Ashley is elated as she drives home from work because she has just received an unexpected promotion and a big raise in salary. As she pulls into her driveway, she notices her elderly neighbor struggling to clear the snow from the sidewalk in front of her home. How will Ashley respond?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 12.5

5. Wei is driving home from school for winter break. Which of the following is not likely to increase his likelibood of behaving aggressively toward other drivers?

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |