13.1 INTRODUCTION:

Stress and Health Psychology

KEY THEME

When events are perceived as exceeding your ability to cope with them, you experience an unpleasant emotional and physical state called stress.

KEY QUESTIONS

What is health psychology, and what is the biopsychosocial model?

How do life events, traumatic events, daily hassles, and burnout contribute to stress?

What are some social and cultural sources of stress?

As the fires raged on, the word stress seemed to be on everyone’s lips. A major disaster in a small city has an impact that spreads far beyond those who are immediately affected. Even people whose homes were nowhere near the fire were tense, preoccupied, and worried. The frequent alerts, evacuation warnings, and ongoing uncertainty kept the city on edge. We all seemed to be holding our collective breath, and it wasn’t just because of the thick, acrid smoke that made breathing difficult. People developed coughs, headaches, insomnia, and nightmares.

A wildfire raging through a densely populated area is an obvious source of psychological stress. However, most sources of stress are more mundane. As a college student, you are undoubtedly very familiar with feeling “stressed out.” Juggling the demands of classes, work, friends, and family can be challenging.

What exactly is stress? It’s one of those words that is frequently used but is hard to define precisely. Early stress researchers, who mostly studied animals, defined stress in terms of the physiological response to harmful or threatening events (see Selye, 1956). However, people are far more complex than animals in their response to potentially stressful events. Two people may respond very differently to the same potentially stressful event. And, as you’ll see, not all stress is unhealthy.

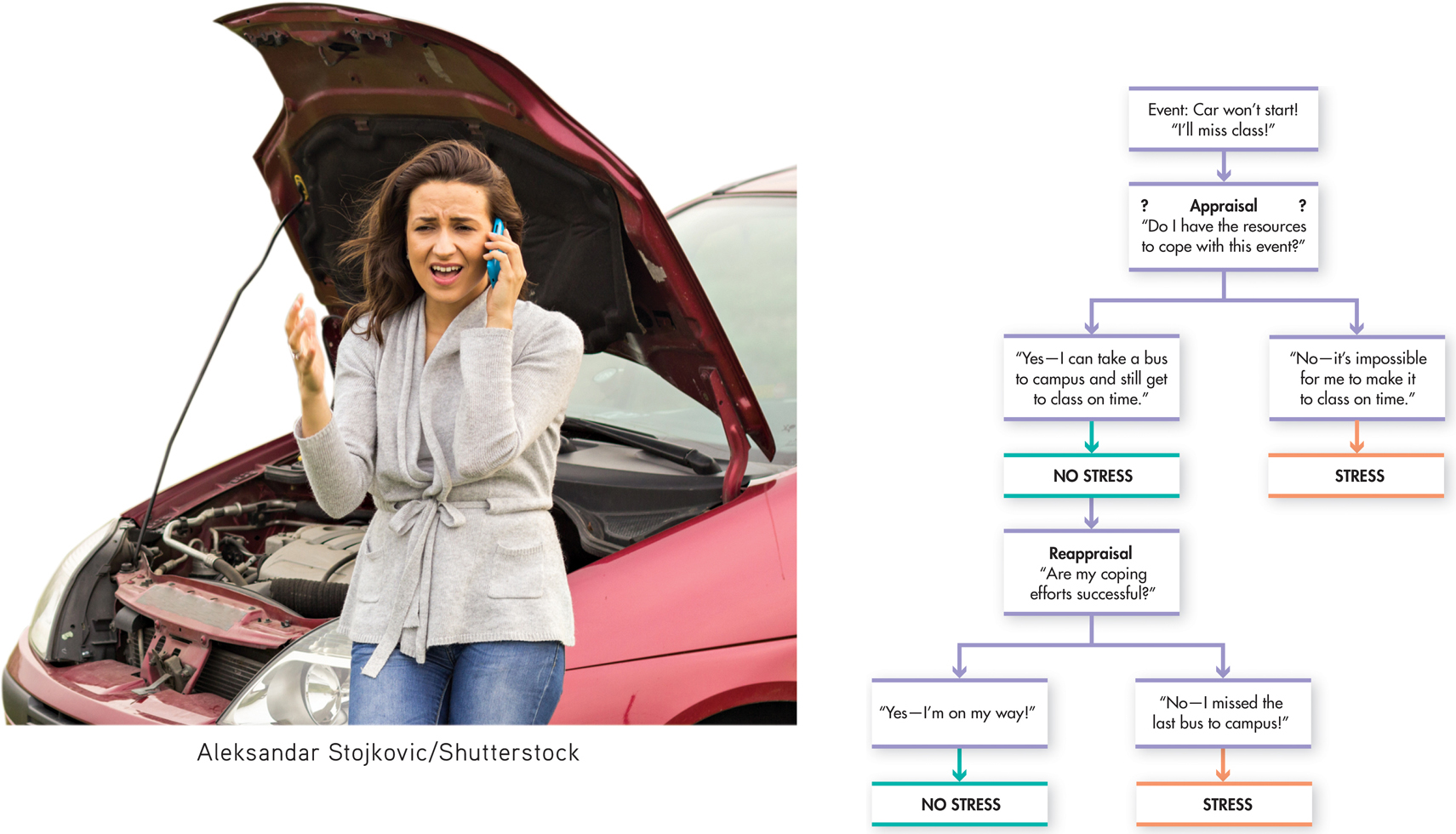

Today, stress is generally defined as a negative emotional state occurring in response to events that are perceived as taxing or exceeding a person’s resources or ability to cope. This definition emphasizes the important role played by a person’s evaluation, or appraisal, of events in the experience of stress. According to the cognitive appraisal model developed by Richard Lazarus, whether we experience stress depends largely on our cognitive appraisal of an event and the resources we have to deal with the event (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Smith & Kirby, 2011).

stress

A negative emotional state occurring in response to events that are perceived as taxing or exceeding a person’s resources or ability to cope.

cognitive appraisal model of stress

Developed by Richard Lazarus, a model of stress that emphasizes the role of an individual’s evaluation (appraisal) of events and situations and of the resources that he or she has available to deal with the event or situation.

If we think that we have adequate resources to deal with a situation, it will probably create little or no stress in our lives. But if we perceive our resources as being inadequate to deal with a situation we see as threatening, challenging, or even harmful, we’ll experience the effects of stress. If our coping efforts are effective, stress will decrease. If they are ineffective, stress will increase. FIGURE 13.1 below depicts the relationship between stress and appraisal.

In this chapter, we’ll take a close look at stress and its effects. We’ll also explore the intricate connections between mind and body—or, more accurately, among emotions, thoughts, behavior, physical responses, and health.

To illustrate how thoughts and feelings can affect physical reactions, try this thought experiment. As vividly as you can, recall a time when a close friend said something that made you angry or hurt your feelings. As you remember the details, note any physical sensations that arise. Can you feel your shoulders tensing, your stomach tightening, or a lump in your throat? Has your heart started beating faster or has your face flushed? If so, your thoughts alone produced a fleeting but concrete physical response.

Can positive thoughts and memories also cause physical changes? To answer this, try another thought experiment. Rather than thinking of a painful incident, make a list of people, circumstances, or items for which you are thankful. The items can be as trivial as finding a parking space or as significant as good health. The content of your list doesn’t matter, but don’t stop until you have managed to come up with at least 10 items, no matter how inconsequential they might seem.

As you become more absorbed in this task, called a gratitude list, note how your body sensations begin to change. Many people begin to experience feelings of relaxation and calmness when they focus their attention on the things in their life for which they are thankful (Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Seligman & others, 2005). If you did, too, you’ve just seen how manipulating your thoughts can produce a positive effect on your body. In fact, studies have shown that actively expressing gratitude is linked to better physical health, better relationships, and lower levels of stress and depression (Seligman & others, 2005; Wood & others, 2008).

The relationship between mind and body is a key element in the field of health psychology, one of the most rapidly growing specialty areas in psychology. Health psychologists are interested in how psychological, social, emotional, and behavioral factors influence health, illness, and treatment.

health psychology

The branch of psychology that studies how biological, behavioral, and social factors influence health, illness, medical treatment, and health-related behaviors.

Decades of research have confirmed that psychological and social factors make major contributions to physical health—and disease (G. E. Miller & others, 2009; Williams & others, 2011). Social factors that contribute to poor health include poverty, discrimination, and lack of access to medical and psychological care. Psychological factors like stress and depression, and other psychological disorders, also contribute to poor health outcomes. Finally, unhealthy behaviors—such as smoking, substance abuse, and sedentary lifestyles—are themselves leading causes of disability, disease, and death in modern society (Adler, 2009). Thus, health psychologists, with their knowledge of the principles of behavior and behavior change, have an important role to play in encouraging the development of healthy lifestyles—and discouraging unhealthy behaviors.

Along with developing strategies to foster emotional and physical well-being, health psychologists investigate issues such as the following:

How to promote health-enhancing behaviors

How people respond to being ill

How people respond in the patient–

health practitioner relationship

Health psychologists work with many different health care professionals, including physicians, nurses, social workers, and occupational and physical therapists. In their research and clinical practice, health psychologists are guided by the biopsychosocial model. According to this model, health and illness are determined by the complex interaction of biological factors, such as genetic predispositions; psychological factors, like health beliefs and attitudes; and social factors, like family relationships and cultural influences (G. E. Miller & others, 2009). In this chapter, we’ll look closely at the roles that different biological, psychological, and social factors play in our experience of health and illness.

biopsychosocial model

The belief that physical health and illness are determined by the complex interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors.

Sources of Stress

Life is filled with potential stressors—events or situations that produce stress. Virtually any event or situation can be a source of stress if you question your ability or resources to deal effectively with it (Cooper & Dewe, 2007; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). In this section, we’ll survey some of the most important and common sources of stress.

stressors

Events or situations that are perceived as harmful, threatening, or challenging.

LIFE EVENTS AND CHANGEIS ANY CHANGE STRESSFUL?

Early stress researchers Thomas Holmes and Richard Rahe (1967) believed that any change that required you to adjust your behavior and lifestyle would cause stress. In an attempt to measure the amount of stress people experienced, they developed the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS). The scale included 43 life events that are likely to require some level of adaptation. Each life event was assigned a numerical rating of its relative impact, ranging from 11 to 100 life change units (see TABLE 13.1). Cross-cultural studies have shown that people in many different cultures tend to rank the magnitude of stressful events in a similar way (McAndrew & others, 1998; Wong & Wong, 2006).

The Social Readjustment Rating Scale: Sample Items

| Life Change | Life Event Units |

|---|---|

| Death of spouse | 100 |

| Divorce | 73 |

| Marital separation | 65 |

| Death of close family member | 63 |

| Major personal injury or illness | 53 |

| Marriage | 50 |

| Fired at work | 47 |

| Retirement | 45 |

| Pregnancy | 40 |

| Change in financial state | 38 |

| Death of close friend | 37 |

| Change to different line of work | 36 |

| Mortgage or loan for major purchase | 31 |

| Foreclosure on mortgage or loan | 30 |

| Change in work responsibilities | 29 |

| Outstanding personal achievement | 28 |

| Begin or end school | 26 |

| Trouble with boss | 23 |

| Change in work hours or conditions | 20 |

| Change in residence | 20 |

| Change in social activities | 18 |

| Change in sleeping habits | 16 |

| Vacation | 13 |

| Christmas | 12 |

| Minor violations of the law | 11 |

| Source: Holmes & Rahe (1967). | |

| The Social Readjustment Rating Scale, developed by Thomas Holmes and Richard Rahe (1967), was an early attempt to quantify the amount of stress experienced by people in a wide range of situations. | |

According to the life events approach, any change, whether positive or negative, is inherently stress-producing. Holmes and Rahe found that people who had accumulated more than 150 life change units within a year had an increased rate of physical or psychological illness (Holmes & Masuda, 1974; Rahe, 1972).

The original life events scale has been revised and updated so that it better weighs the influences of gender, age, marital status, and other individual characteristics (Hobson & Delunas, 2001). New scales have also been developed for specific groups (Dohrenwend, 2006). For instance, the College Student Stress Scale measures unique experiences of college student life that contribute to stress, such as “flunking a class” and “difficulties with parents” (Feldt, 2008).

Despite its popularity, there are several problems with the life events approach. First, the link between scores on the SRRS and the development of physical and psychological problems is relatively weak. In fact, researchers have found that most people weather major life events without developing serious physical or psychological problems (Monroe & Reid, 2009).

Second, the SRRS assumes that a given life event will have the same impact on virtually everyone. But clearly, the stress-producing potential of an event might vary widely from one person to another. For example, if you are in a marriage that is filled with conflict, getting divorced (73 life change units) might be significantly less stressful than remaining married.

Third, the life events approach assumes that change in itself, whether good or bad, produces stress. However, researchers have found that negative life events have a more adverse effect on health than positive events (Hatch & Dohrenwend, 2007). Today, most researchers agree that undesirable events are significant sources of stress but that change in itself is not necessarily stressful.

TRAUMATIC EVENTS

One category of life events deserves special mention. Traumatic events are events or situations that are negative, severe, and far beyond our normal expectations for everyday life or life events (Robinson & Larson, 2010). Witnessing or surviving a violent attack, serious accident, and experiences associated with combat, war, or major disasters are examples of the types of events that are typically considered to be traumatic.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that most people exposed to severe trauma will develop PTSD or other serious psychological problems?

Traumatic events are surprisingly common, especially among young adults. One large survey of college students found that 85% reported having been exposed to a traumatic event during their lifetime (Frazier & others, 2009). The most common traumatic events experienced by college students were the unexpected death of a loved one, sexual assault, and family violence.

Traumatic events, even relatively mild ones like a minor car accident, can be very stressful. When traumas are intense or repeated, some psychologically vulnerable people may develop posttraumatic stress disorder (abbreviated PTSD). As we will see in Chapter 14, PTSD is a disorder that involves intrusive thoughts of the traumatic event, emotional numbness, and symptoms of anxiety, such as nervousness, sleep disturbances, and irritability. However, it’s important to note that most people recover from traumatic events without ever developing PTSD (Seery & others, 2010). For example, research shows that less than 30% of those who experience major disasters—such as floods, earthquakes, and hurricanes—develop PTSD (Bonanno & others, 2011). In reality, most people are remarkably resilient—a topic we discuss next.

DEVELOPING RESILIENCE

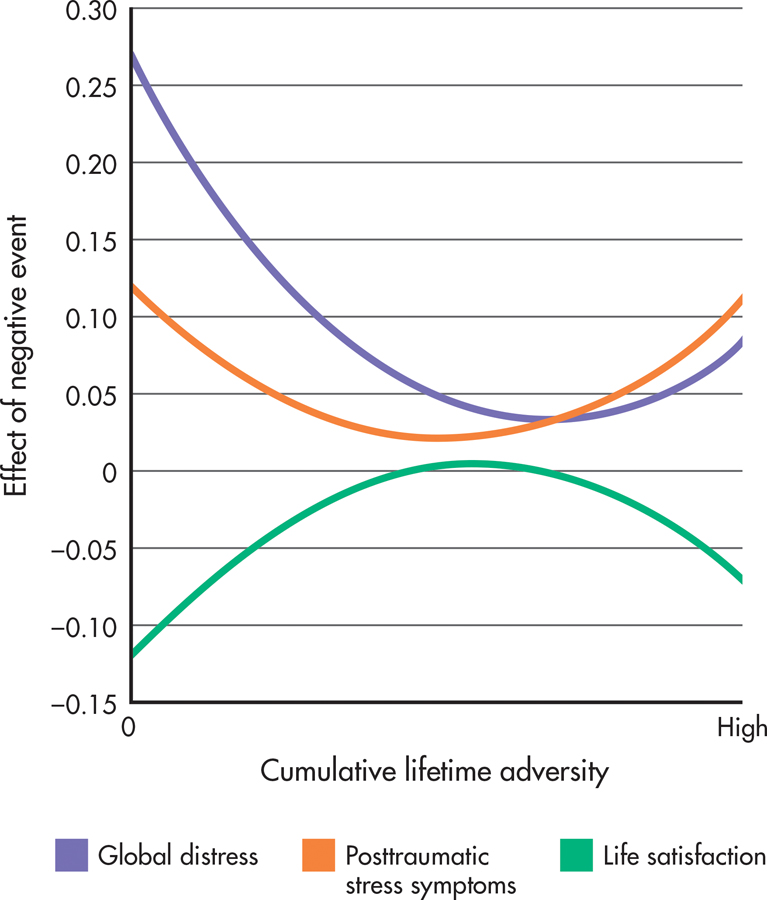

There’s a famous saying that “whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” Psychologist Mark Seery and his colleagues (2010) set out to test that hypothesis in a multi-year, longitudinal study of the relationship between well-being and exposure to negative life events. They carefully measured health outcomes and cumulative adversity—defined as the total amount of negative events experienced over a lifetime—in a large, representative sample of U.S. adults.

Seery and his colleagues (2010) found that, as expected, high levels of cumulative adversity were associated with poor health outcomes. But, it turned out, so were very low levels of adversity. As shown in FIGURE 13.2, faring best of all were people with a moderate level of adversity. They were not only healthier, but also better able to cope with recent misfortune than people who had experienced either very low or high levels of adversity. Experiencing some stress was healthier than experiencing no stress at all.

Why might experiencing some adversity be healthier, in the long run, than living a charmed, stress-free life? Seery argues that people who are never exposed to stressful, difficult events don’t develop the ability to cope with adversity when it does occur—as it eventually does. And, because they lack confidence in their coping abilities, even minor setbacks can be perceived as overwhelming.

In contrast, people who have had to cope with a moderate level of adversity develop resilience—the ability to cope with stress and adversity, to adapt to negative or unforeseen circumstances, and to rebound after negative experiences. Just as moderate exercise builds muscle and aerobic capacity, leading to physical fitness, moderate experience of adversity builds resilience.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that all stress is bad for you?

DAILY HASSLESTHAT’S NOT WHAT I ORDERED!

What made you feel “stressed out” in the past week? Chances are, it was not a major life event. Instead, it was probably some unexpected but minor annoyance, such as splotching ketchup on your new T-shirt, misplacing your keys, or getting into an argument with your roommate or a close friend.

Stress researcher Richard Lazarus and his colleagues suspected that such ordinary irritations in daily life might be an important source of stress. To explore this idea, they developed a scale measuring daily hassles—everyday occurrences that annoy and upset people (DeLongis & others, 1982; Kanner & others, 1981). TABLE 13.2 lists examples from the original Daily Hassles Scale and from other scales developed for specific populations.

daily hassles

Everyday minor events that annoy and upset people.

Examples of Daily Hassles

| Daily Hassles Scale |

|---|

| • Concern about weight |

| • Concern about health of family member |

| • Not enough money for housing |

| • Too many things to do |

| • Misplacing or losing things |

| • Too many interruptions |

| • Don’t like current work duties |

| • Traffic |

| • Car repairs or transportation problems |

| College Daily Hassles Scale |

| • Increased class workload |

| • Troubling thoughts about your future |

| • Fight with boyfriend/girlfriend |

| • Concerns about meeting high standards |

| • Wasting time |

| • Computer problems |

| • Concerns about failing a course |

| • Concerns about money |

| Acculturative Daily Hassles for Children |

| • It bothers me when people force me to be like everyone else. |

| • Because of the group I’m in, I don’t get the grades I deserve. |

| • I don’t feel at home here in the United States. |

| • People think I’m shy, when I really just have trouble speaking English. |

| • I think a lot about my group and its culture. |

| Sources: Research from Blankstein & Flett, 1992; Kanner & others, 1981; Ross & others, 1999; Staats & others, 2007; Suarez-Morales & others, 2007. |

| Arguing that “daily hassles” could be just as stress-inducing as major life events, Richard Lazarus and his colleagues constructed a 117-item Daily Hassles Scale. Later, other researchers developed daily hassles scales for specific groups. |

The frequency of daily hassles is linked to mental and physical illness, unhealthy behaviors, and decreased well-being (O’Connor & others, 2008). Some researchers have found that the number of daily hassles people experience is a better predictor of physical illness and symptoms than is the number of major life events experienced (Almeida & others, 2005).

Why do daily hassles take such a toll? One explanation is that such minor stressors are cumulative (Grzywacz & Almeida, 2008). Each hassle may be relatively unimportant in itself, but after a day or two filled with minor hassles, the effects add up. People feel drained, grumpy, and stressed out.

Daily hassles also contribute to the stress produced by major life events. Any major life change can create a ripple effect, generating a host of new daily hassles (Maybery & others, 2007). For example, people who lost their homes in the wildfire had to scramble to find temporary housing and purchase clothes, furniture, pots and pans, and all the other essentials of everyday life that we take for granted. Those who had insurance had to navigate a nightmarish maze of paperwork and regulations. As Andi said, “Imagine if you picked up your house, turned it upside down, and shook it. Now imagine having to describe each and every item that fell out, including where you got it and how much it cost. Think about doing that for every towel, sock, pair of jeans, plate and coffee cup and rug and T-shirt and dog toy that you own. It’s a nightmare.”

Are there gender differences in the experience of daily hassles? Interpersonal conflict is the most common source of daily stress for both men and women (Almeida & others, 2005). However, women are more likely to report daily stress that is associated with friends and family, while males are more likely to feel hassled by stressors that are school-or work-related (Zwicker & DeLongis, 2010).

For both sexes, stress at work or school tends to affect home life (Bodenmann & others, 2010). For women, daily stress tends to spill over into their interactions with their partners. Men, on the other hand, are more likely to simply withdraw. In fact, one study found that the most likely place to find a father after a stressful day at work was sitting alone in a room (Repetti & others, 2009).

WORK STRESS AND BURNOUTIS IT QUITTING TIME YET?

Whether it be due to concerns about job security, unpleasant working conditions, difficult co-workers and supervisors, or unreasonable demands and deadlines, work stress can produce a pressure cooker environment that takes a significant toll on your physical health (Nakao, 2010). It can also increase the likelihood of unhealthy behaviors. For example, college students who experienced high levels of work stress also consumed more alcohol than other students (Butler & others, 2010).

When work stress is prolonged and becomes chronic, it can produce a stress response called burnout. There are three key components of burnout (Maslach & Leiter, 2005, 2008). People feel exhausted, as if they’ve used up all of their emotional and physical resources. Second, people experience feelings of cynicism, demonstrating negative or overly detached attitudes toward the job or work environment. People often feel unappreciated or as if they are being treated unfairly at work (Demerouti & others, 2010). Third, people feel a sense of failure or inadequacy. They may feel incompetent and have a sharply reduced sense of accomplishment or productivity.

burnout

An unhealthy condition caused by chronic, prolonged work stress that is characterized by exhaustion, cynicism, and a sense of failure or inadequacy.

One workplace condition that commonly produces burnout is work overload, when the demands of the job exceed the worker’s ability to meet them (Maslach & Leiter, 2008). A second is lack of control. Generally, the more control you have over your work and work environment, the less stressful it is (Q. Wang & others, 2010). Complex, demanding jobs are much less likely to produce feelings of overload, burnout, or stress when workers have control over how they perform those jobs (Chung-Yan, 2010).

However, even in high-stress occupations or demanding work environments, burnout can be prevented. Burnout is least likely to occur when there is a sense of community in the workplace (Maslach & Leiter, 2008). Supportive co-workers, a sense of teamwork, and a positive work environment can all buffer workplace stress and prevent burnout.

SOCIAL AND CULTURAL SOURCES OF STRESS

For disadvantaged groups exposed to crowding, crime, poverty, and substandard housing, everyday living conditions can be a significant source of stress (Gallo & others, 2009; Meyer & others, 2008). People who live under difficult or unpleasant conditions often experience ongoing, or chronic, stress (Adler & Rehkopf, 2008).

Chronic stress is also associated with lower socioeconomic status (SES), which is a measure of overall status in society (Chandola & Marmot, 2011). The core components of SES are income, education, and occupation. One finding that has been consistent over time and across multiple cultures is the strong association of physical health and longevity with SES (Adler, 2009).

People in lower SES groups tend to experience more negative life events and more daily hassles than people in more privileged groups (Hatch & Dohrenwend, 2007). Disadvantaged teenagers and young adults are especially likely to experience high levels of stressful events, particularly violent or life-threatening events. People in less privileged groups also tend to have fewer resources to help them cope with the stressors that they do experience. Thus, it’s not surprising that people in the lowest socioeconomic levels tend to have the highest levels of psychological distress, illness, and premature death (Braveman & others, 2010).

Beyond these external factors, low social status is in itself highly stressful (Hackman & others, 2010). Many studies have shown that perceiving yourself as being of low social status is associated with poorer physical health—regardless of your objective social status as measured by traditional SES measures (Adler, 2009).

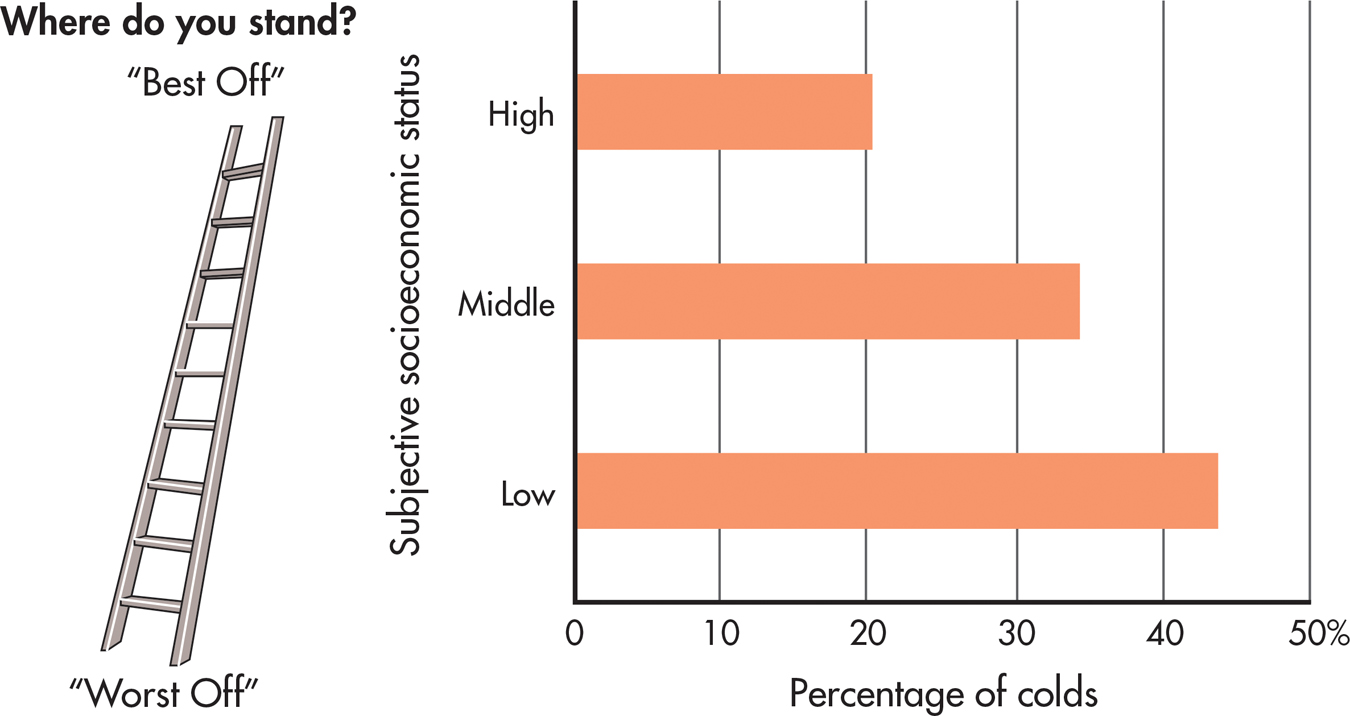

The powerful effects of perceived social status were convincingly demonstrated in a recent study (Cohen & others, 2008). Volunteers were exposed to a cold virus (see FIGURE 13.3). The volunteers who saw themselves as being low on the social status totem pole had higher rates of infection than volunteers who objectively matched them on social status measures but subjectively did not see themselves as being of low status (Cohen & others, 2008).

Racism and discrimination are other important sources of chronic stress for many people (Brondolo & others, 2011; Ong & others, 2009). In one survey, for example, more than three-quarters of African American adolescents reported being treated as incompetent or dangerous—or both—because of their race (Sellers & others, 2006). Such subtle instances of racism, called microaggressions, take a cumulative toll (Sue & others, 2008). Whether it’s subtle or blatant, racism significantly contributes to the chronic stress often experienced by members of minority groups.

Stress can also result when cultures clash. For refugees, immigrants, and their children, adapting to a new culture can be extremely stress-producing (Berry, 2003; Jamil & others, 2007). The Culture and Human Behavior box “The Stress of Adapting to a New Culture” below describes factors that influence the degree of stress experienced by people encountering a new culture.

CULTURE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

The Stress of Adapting to a New Culture

Refugees, immigrants, and even international students are often unprepared for the dramatically different values, language, food, customs, and climate that await them in their new land. The process of changing one’s values and customs as a result of contact with another culture is referred to as acculturation. Acculturative stress is the stress that results from the pressure of adapting to a new culture (Sam & Berry, 2010).

acculturative stress

(uh-CUL-chur-uh-tiv) The stress that results from the pressure of adapting to a new culture.

Many factors can influence the degree of acculturative stress that a person experiences. For example, when the new society accepts ethnic and cultural diversity, acculturative stress is reduced (Mana & others, 2009). The transition is also eased when the person has some familiarity with the new language and customs, advanced education, and social support from friends, family members, and cultural associations (Schwartz & others, 2010). Acculturative stress is also lower if the new culture is similar to the culture of origin.

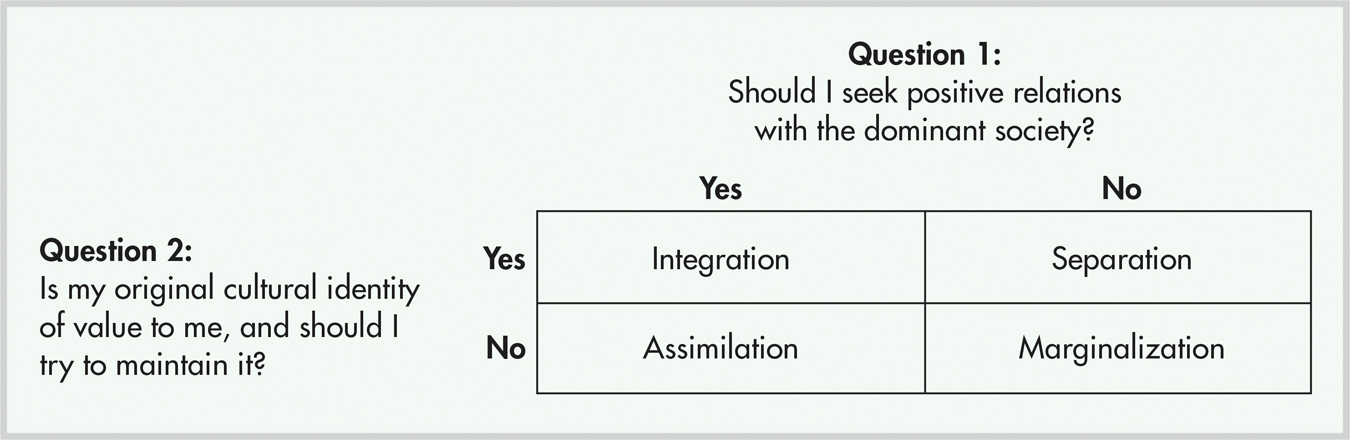

Cross-cultural psychologist John Berry (2003, 2006) has found that a person’s attitudes are important in determining how much acculturative stress is experienced (Sam & Berry, 2010). When people encounter a new cultural environment, they are faced with two questions: (1) Should I seek positive relations with the dominant society? (2) Is my original cultural identity of value to me, and should I try to maintain it?

The answers produce one of four possible patterns of acculturation: integration, assimilation, separation, or marginalization (see the diagram). Each pattern represents a different way of coping with the stress of adapting to a new culture (Berry, 1994, 2003).

Integrated individuals continue to value their original cultural customs but also seek to become part of the dominant society. They embrace a bicultural identity (Huynh & others, 2011). Biculturalism is associated with higher self-esteem and lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, suggesting that the bicultural identity may be the most adaptive acculturation pattern (Schwartz & others, 2010). In fact, a meta-analysis of 83 studies showed that biculturalism had the strongest association with psychological and social adjustment (Nguyen & Benet-Martínez, 2013). The successfully integrated individual’s level of acculturative stress will be low (Lee, 2010).

Assimilated individuals give up their old cultural identity and try to become part of the new society. They adopt the customs and social values of the new environment, and abandon their original cultural traditions.

Assimilation usually involves a moderate level of stress, partly because it involves a psychological loss—one’s previous cultural identity. People who follow this pattern also face the possibility of being rejected either by members of the majority culture or by members of their original culture (Schwartz & others, 2010). The process of learning new behaviors and suppressing old behaviors can also be moderately stressful.

Individuals who follow the pattern of separation maintain their cultural identity and avoid contact with the new culture. They may refuse to learn the new language, live in a neighborhood that is primarily populated by others of the same ethnic background, and socialize only with members of their own ethnic group.

In some cases, separation is not voluntary, but is due to the dominant society’s unwillingness to accept the new immigrants. Thus, it can be the result of discrimination. Whether voluntary or involuntary, the level of acculturative stress associated with separation tends to be high.

Finally, marginalized people lack cultural and psychological contact with both their traditional cultural group and the culture of their new society. By taking the path of marginalization, they lost the important features of their traditional culture but have not replaced them with a new cultural identity.

Although rare, the path of marginalization is associated with the greatest degree of acculturative stress. Marginalized individuals are stuck in an unresolved conflict between their traditional culture and the new society, and may feel as if they don’t really belong anywhere. Fortunately, only a small percentage of immigrants fall into this category (Schwartz & others, 2010).