13.3 Individual Factors That Influence the Response to Stress

KEY THEME

Psychologists have identified several psychological factors that can modify an individual’s response to stress and affect physical health.

KEY QUESTIONS

How do feelings of control, explanatory style, and negative emotions influence stress and health?

What is Type A behavior, and what role does hostility play in the relationship between Type A behavior and health?

People vary a great deal in the way they respond to a distressing event, whether it’s a parking ticket or a bad grade on a crucial exam. In part, individual differences in reacting to stressors result from how people appraise an event and their resources for coping with the event. However, psychologists and other researchers have identified several factors that influence an individual’s response to stressful events. In this section, we’ll take a look at some of the most important psychological and social factors that seem to affect an individual’s response to stress.

Psychological Factors

It’s easy to demonstrate the importance of psychological factors in the response to stressors. For example, sit in a crowded waiting room and watch how differently people react to news of delays or cancelled appointments. Some people take the news calmly, while others become enraged and indignant. Psychologists have confirmed what common sense suggests: Psychological processes play a key role in determining the level of stress experienced.

PERSONAL CONTROL

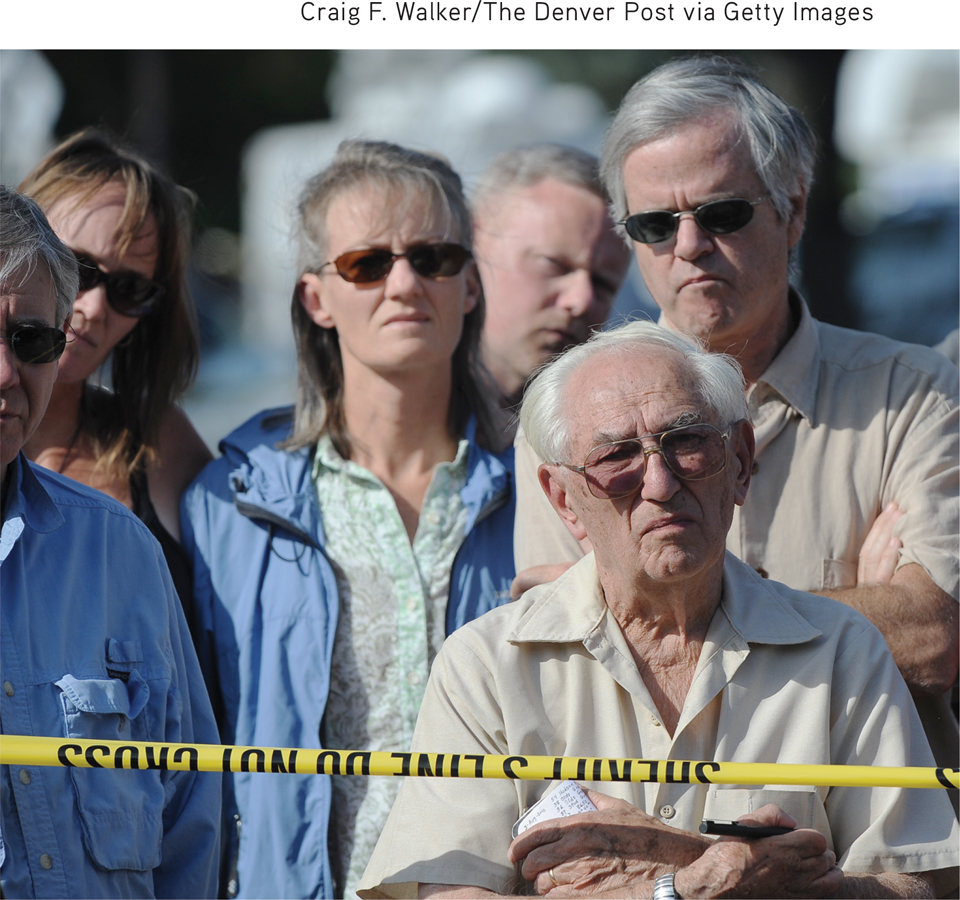

For five days the fires raged. Every night, Hawk sat in front of her friend’s TV watching the news, wondering whether the house she was born in was still standing but knowing that there was absolutely nothing she could do to help protect it. Despite the nonstop coverage, there was no new information—just more images of burnt houses and flames flickering all over the mountainsides. Hawk had never felt so helpless in her entire life.

Whether it be a wildfire threatening your home or a cancelled airline flight, situations that you perceive as being beyond your control are highly stressful. In contrast, having a sense of control over a stressful situation reduces the impact of stressors and decreases feelings of anxiety and depression (Thompson, 2009). People who can control a stress-producing event often show no more psychological distress or physical arousal than people who are not exposed to the stressor at all.

Psychologists Judith Rodin and Ellen Langer (1977) first demonstrated the importance of a sense of control in a classic series of studies with nursing home residents. One group of residents—the “high-control” group—was given the opportunity to make choices about their daily activities and to exercise control over their environment. In contrast, residents assigned to the “low-control” group had little control over their daily activities. Decisions were made for them by the nursing home staff. Eighteen months later, the high-control residents were more active, alert, sociable, and healthier than the low-control residents. And, twice as many of the low-control residents had died (Langer & Rodin, 1976; Rodin & Langer, 1977).

How does a sense of control affect health? If you feel that you can control a stressor by taking steps to minimize or avoid it, you will experience less stress, both subjectively and physiologically (Heth & Somer, 2002; Heth & others, 2004). Having a sense of personal control also enhances positive emotions, such as self-confidence and feelings of self-efficacy, autonomy, and self-reliance. In contrast, feeling a lack of control over events produces all the hallmarks of the stress response. Levels of catecholamines and corticosteroids increase, and the effectiveness of immune system functioning decreases (see Maier & Watkins, 2000).

However, the perception of personal control in a stressful situation must be realistic to be adaptive (Segerstrom & Roach, 2008). Studies of people with chronic diseases, like heart disease and arthritis, have shown that unrealistic perceptions of personal control contribute to stress and poor adjustment (Affleck & others, 1987a, 1987b).

Further, not everyone benefits from feelings of enhanced personal control. Cross-cultural studies have shown that a sense of control is more highly valued in individualistic, Western cultures than in collectivistic, Eastern cultures (Thompson, 2009). Comparing Japanese and British participants, Darryl O’Connor and Mikiko Shimizu (2002) found that a heightened sense of personal control was associated with a lower level of perceived stress—but only among the British participants.

EXPLANATORY STYLEOPTIMISM VERSUS PESSIMISM

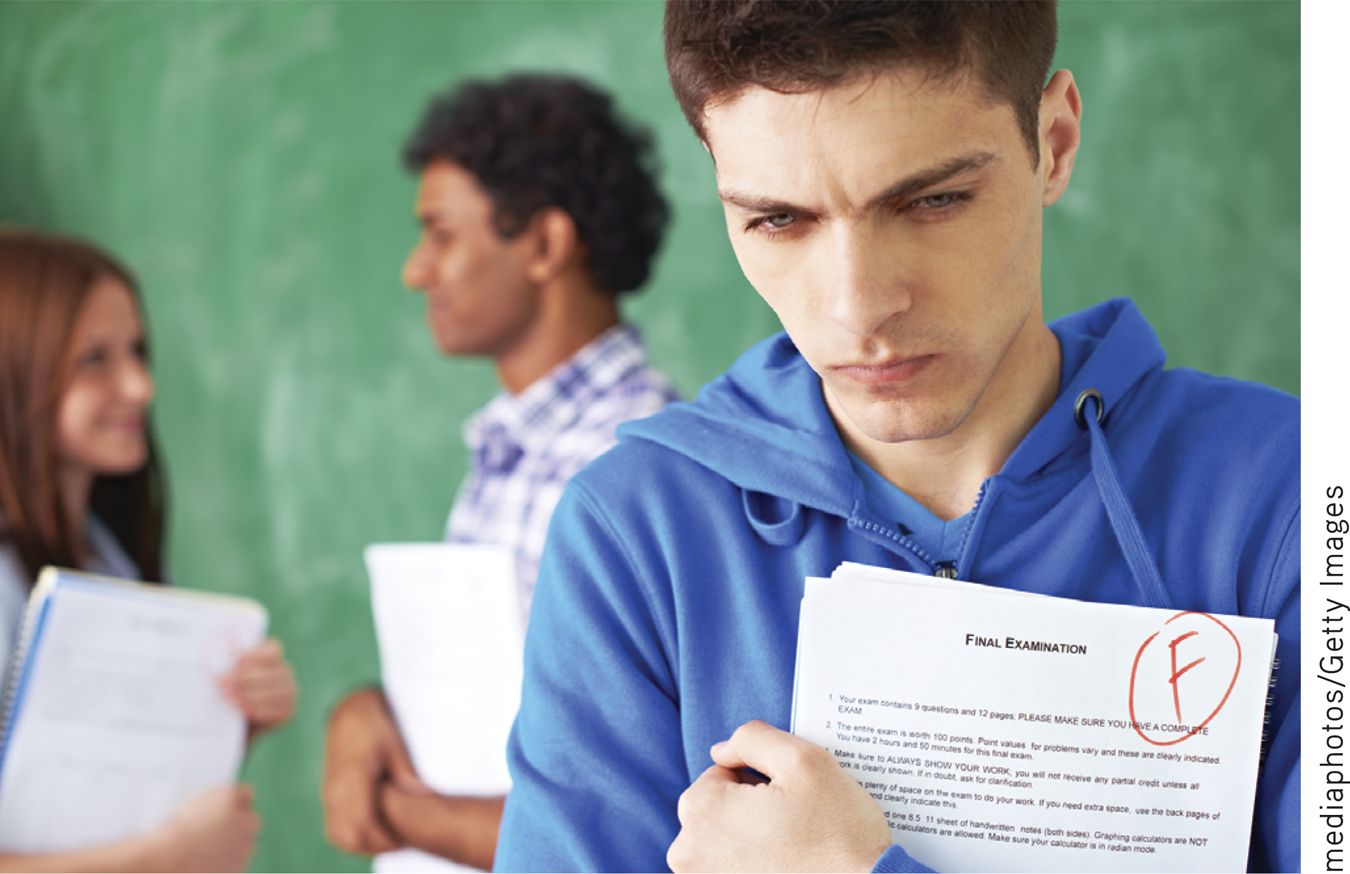

We all experience defeat, rejection, or failure at some point in our lives. Yet despite repeated failures, rejections, or defeats, some people persist in their efforts. In contrast, some people give up in the face of failure and setbacks—the essence of learned helplessness, which we discussed in Chapter 5. What distinguishes between those who persist and those who give up?

According to psychologist Martin Seligman (1990, 1992), how people characteristically explain their failures and defeats makes the difference. People who have an optimistic explanatory style tend to use external, unstable, and specific explanations for negative events. In contrast, people who have a pessimistic explanatory style use internal, stable, and global explanations for negative events. Pessimists are also inclined to believe that no amount of personal effort will improve their situation. Not surprisingly, pessimists tend to experience more stress than optimists.

optimistic explanatory style

Accounting for negative events or situations with external, unstable, and specific explanations.

pessimistic explanatory style

Accounting for negative events or situations with internal, stable, and global explanations.

Let’s look at these two explanatory styles in action. Optimistic Olive sees an attractive guy at a party and starts across the room to introduce herself and strike up a conversation. As she approaches him, the guy glances at her, then abruptly turns away. Hurt by the obvious snub, Optimistic Olive retreats to the buffet table. Munching on some fried zucchini, she mulls the matter over in her mind. At the same party, Pessimistic Pete sees an attractive female across the room and approaches her. He, too, gets a cold shoulder and retreats to the chips and clam dip. Standing at opposite ends of the buffet table, here is what each of them is thinking:

OPTIMISTIC OLIVE: What’s his problem? (External explanation: The optimist blames other people or external circumstances.)

PESSIMISTIC PETE: I must have said the wrong thing. She probably saw me stick my elbow in the clam dip before I walked over. (Internal explanation: The pessimist blames self.)

OPTIMISTIC OLIVE: I’m really not looking my best tonight. I’ve just got to get more sleep. (Unstable, temporary explanation)

PESSIMISTIC PETE: Let’s face it, I’m a pretty boring guy and really not very good-looking. (Stable, permanent explanation)

OPTIMISTIC OLIVE: He looks pretty preoccupied. Maybe he’s waiting for his girlfriend to arrive. Or his boyfriend! (Specific explanation)

PESSIMISTIC PETE: Women never give me a second look, probably because I dress like a nerd and I never know what to say to them. (Global, pervasive explanation)

OPTIMISTIC OLIVE: Whoa! Who’s that guy over there?! Okay, Olive, turn on the charm! Here goes! (Perseverance after a rejection)

PESSIMISTIC PETE: Maybe I’ll just hold down this corner of the buffet table … or go home and soak up some TV. (Passivity and withdrawal after a rejection)

Most people, of course, are neither as completely optimistic as Olive nor as totally pessimistic as Pete. Instead, they fall somewhere along the spectrum of optimism and pessimism. Further, explanatory style may vary somewhat in different situations (Fosnaugh & others, 2009). Even so, a person’s characteristic explanatory style, particularly for negative events, is relatively stable across the lifespan (Abela & others, 2008).

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that pessimists handle stress better because they expect bad things to happen?

Explanatory style is linked to health consequences (Brummett & others, 2006; Wise & Rosqvist, 2006). For example, men with an optimistic explanatory style at age 25 were significantly healthier at age 50 than men with a pessimistic explanatory style (Peterson & Park, 2007). Other studies have shown that a pessimistic explanatory style is associated with poorer physical health (Peterson & Steen, 2009). For example, first-year law school students who had an optimistic, confident, and generally positive outlook had significantly higher levels of lymphocytes, T cells, and helper T cells. Explaining the positive relationship between optimism and good health, Suzanne Segerstrom and her colleagues (2003) suggest that optimists are more inclined to persevere in their efforts to overcome obstacles and challenges. Optimists are also more likely to cope effectively with stressful situations than pessimists (Iwanaga & others, 2004).

CHRONIC NEGATIVE EMOTIONSTHE HAZARDS OF BEING GROUCHY

Some people seem to have been born with a sunny, cheerful disposition. But other people almost always seem to be unhappy campers—they frequently experience bad moods and negative emotions like anger, irritability, worry, or sadness (D. J. Miller & others, 2009). Are people who are prone to chronic negative emotions more likely to suffer health problems?

Many studies have found a strong link between negative emotions and poor health (see Lahey, 2009). For example, a meta-analysis of more than 100 studies found that people who are habitually anxious, depressed, angry, or hostile are more likely to develop a chronic disease such as arthritis or heart disease (Friedman & Booth-Kewley, 2003).

How might chronic negative emotions predispose people to develop disease? Not surprisingly, tense, angry, and unhappy people experience more stress than do happier people. They also report more daily hassles than people who are generally in a positive mood (McIntyre & others, 2008). And, they react much more intensely, and with far greater distress, to stressful events (Lahey, 2009). Of course, everyone occasionally experiences bad moods or has a bad day. Are these fluctuations in mood associated with health risks? Some studies suggest that even transient increases in negative mood are associated with unhealthy cardiovascular and hormone responses (Daly & others, 2010; Jacobs & others, 2007).

POSITIVE EMOTIONS

If negative emotions are associated with poor health, are positive emotions associated with good health? First, positive emotions are not just the absence of negative emotions (Larsen & others, 2009). The health benefits of experiencing positive emotions go beyond merely dampening or eliminating negative emotions.

Research has shown that positive emotions are associated with increased resistance to infection, decreased illnesses, fewer reports of illness symptoms, less pain, and longevity (Pressman & Cohen, 2005; Steptoe & others, 2009). One large Canadian study found that people who experienced high levels of positive emotion were less likely to develop heart disease than people who reported low levels of positive emotions (Davidson & others, 2010).

How might positive emotions affect health? First, positive emotions bring calming and health protective effects to the cardiovascular, endocrine, and immune systems (Brummett & others, 2009). Second, positive emotions are associated with health-promoting behaviors, such as regular exercise, eating a healthy diet, and not smoking. Finally, individuals who frequently experience positive emotions tend to have more friends and stronger social networks than people who don’t (Steptoe & others, 2009).

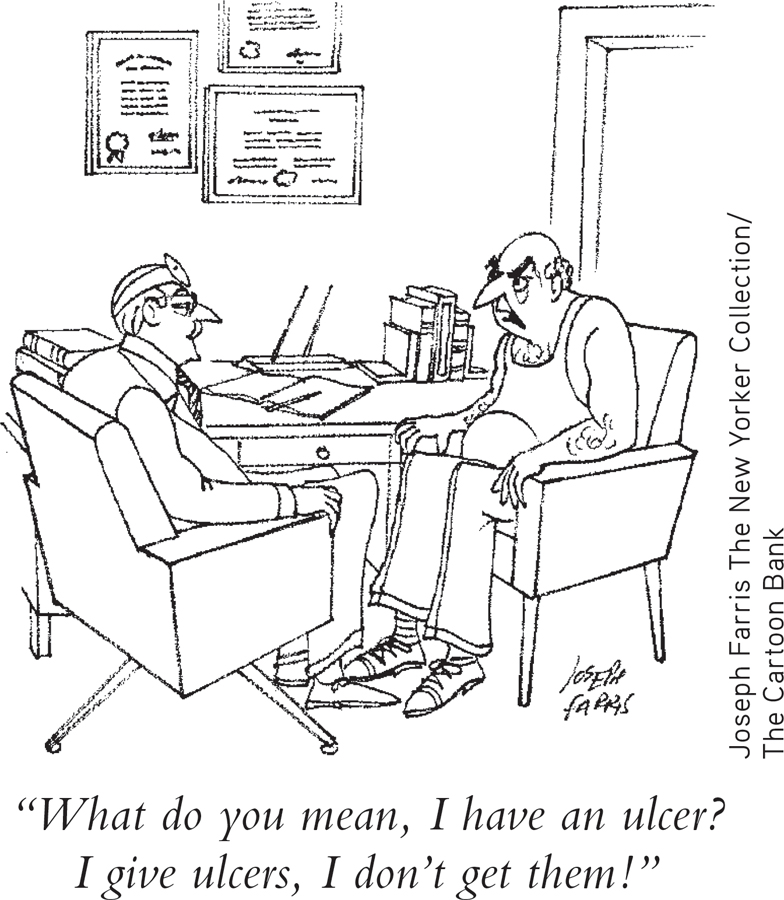

TYPE A BEHAVIOR AND HOSTILITY

The concept of Type A behavior originated about 35 years ago, when two cardiologists, Meyer Friedman and Ray Rosenman (1974), noticed that many of their patients shared certain traits. The original formulation of the Type A behavior pattern included a cluster of three characteristics: (1) an exaggerated sense of time urgency, often trying to do more and more in less and less time; (2) a general sense of hostility, frequently displaying anger and irritation; and (3) intense ambition and competitiveness. In contrast, people who were more relaxed and laid back were classified as displaying the Type B behavior pattern. After tracking the health of more than 3,000 middle-aged, healthy men, they found that those classified as Type A were twice as likely to develop heart disease as those classified as Type B. This held true even when the Type A men did not display other known risk factors for heart disease, such as smoking, high blood pressure, and elevated levels of cholesterol in their blood.

Type A behavior pattern

A behavioral and emotional style characterized by a sense of time urgency, hostility, and competitiveness.

Although early results linking the Type A behavior pattern to heart disease were impressive, studies soon began to appear in which Type A behavior did not reliably predict the development of heart disease (see Krantz & McCeney, 2002; Myrtek, 2007). These findings led researchers to question whether the different components of the Type A behavior pattern were equally hazardous to health. After all, many people thrive on hard work, especially when they enjoy their jobs. And, high achievers don’t necessarily suffer from health problems.

When researchers focused on the association between heart disease and each separate component of the Type A behavior pattern—time urgency, hostility, and achievement striving—an important distinction began to emerge. Feeling a sense of time urgency and being competitive or achievement oriented did not seem to be associated with the development of heart disease. Instead, the critical component that emerged as the strongest predictor of cardiac disease was hostility (Chida & Steptoe, 2009; J. E. Williams, 2010). Hostile people are much more likely than other people to develop heart disease, even when other risk factors are taken into account (Niaura & others, 2002; J. E. Williams, 2010).

How does hostility predispose people to heart disease and other health problems? Hostility refers to the tendency to feel anger, annoyance, resentment, and contempt, and to hold cynical and negative beliefs about human nature in general. Hostile people are also prone to believing that the disagreeable behavior of others is intentionally directed against them. Thus, hostile people tend to be suspicious, mistrustful, cynical, and pessimistic.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that high-achieving people who work long hours are setting themselves up for a heart attack?

Thus, hostile Type As tend to react more intensely to a stressor than other people do (Chida & Hamer, 2008). They experience greater increases in blood pressure and heart rate. Because of their attitudes and behavior, hostile men and women also tend to create more stress in their own lives (Suls & Bunde, 2005). They also tend to experience more frequent, and more severe, negative life events and daily hassles than other people.

In general, the research evidence demonstrating the role of personality factors in the development of stress-related disease is impressive. Nevertheless, it’s important to keep this evidence in perspective: Personality characteristics are just some of the many factors involved in the overall picture of health and disease. We look at this issue in more detail in the Critical Thinking box below. And, in Psych for Your Life, at the end of this chapter, we describe some of the steps you can take to help you minimize the effects of stress on your health.

CRITICAL THINKING

Do Personality Factors Cause Disease?

You overhear a co-worker saying, “I’m not surprised he had a heart attack—the guy is a workaholic!”

An acquaintance casually remarks, “She’s been so depressed since her divorce. No wonder she got cancer.”

A tabloid headline hails, “New Scientific Findings: Use Your Mind to Cure Cancer!”

Statements like these make health psychologists, psychoneuroimmunologists, and physicians extremely uneasy. Why? Throughout this chapter, we’ve presented scientific evidence that emotional states can affect the functioning of the endocrine system and the immune system. Both systems play a significant role in the development of various physical disorders. We’ve also shown that personality factors, such as hostility and pessimism, are associated with an increased likelihood of developing poor health. But saying that “emotions affect the immune system” is a far cry from making such claims as “a positive attitude can cure cancer.”

Psychologists and other scientists are cautious in the statements they make about the connections between personality and health for several reasons. First, many studies investigating the role of psychological factors in disease are correlational. That is, researchers have statistical evidence that two factors happen together so often that the presence of one factor reliably predicts the occurrence of the other. However, correlation does not necessarily indicate causality—it indicates only that two factors occur together. It’s completely possible that some third, unidentified factor may have caused the other two factors to occur.

Second, personality factors might indirectly lead to disease via poor health habits. Low conscientiousness, high sensation seeking, and high extraversion are each associated with poor health habits (Lodi-Smith & others, 2010; Miller & Quick, 2010; Raynor & Levine, 2009). In turn, poor health habits are associated with higher rates of illness. That’s why psychologists who study the role of personality factors in disease are typically careful to measure and consider the possible influence of the participants’ health practices.

Third, it may be that the disease influences a person’s emotions, rather than the other way around (Spezzaferri & others, 2009). After being diagnosed with advanced cancer or heart disease, most people would probably find it difficult to feel cheerful, optimistic, or in control of their lives.

One way that researchers try to disentangle the relationship between personality and health is to conduct carefully controlled prospective studies. A prospective study starts by assessing an initially healthy group of participants on variables thought to be risk factors, such as certain personality traits. Then the researchers track the health, personal habits, health habits, and other important dimensions of the participants’ lives over a period of months, years, or decades. In analyzing the results, researchers can determine the extent to which each risk factor contributed to the health or illness of the participants. Thus, prospective studies provide more compelling evidence than do studies that are based on people who are already in poor health.

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

Given that health professionals frequently advise people to change their health-related behaviors to improve physical health, should they also advise people to change their psychological attitudes, traits, and emotions? Why or why not?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of correlational studies? Prospective studies?

CONCEPT REVIEW 13.2

Psychological Factors and Stress

Identify the psychological characteristic that is best illustrated by each of the examples below.

Question

chronic negative emotions pessimistic explanatory style high level of personal control Type A behavior pattern optimistic explanatory style | Cheryl was despondent when she received a low grade on her algebra test. She said, “I will never do well on exams because I’m not very smart. I might as well drop out of school now before I flunk out.” No matter what happens to her, Lucy is dissatisfied and grumpy. She constantly complains about her health, her job, and how awful her life is. She dislikes most of the people she meets. Max flubbed an easy free throw in the big basketball game but told his coach, “My game was off today because I’m still getting over the flu and I pulled a muscle in practice yesterday. I’ll do better in next week’s game.” Richard is a very competitive, ambitious stockbroker who is easily irritated by small inconveniences. If he thinks that someone is wasting his time, he blows up and becomes completely enraged. In order to deal with the high levels of stress associated with returning to college full-time, Pat selected her courses carefully, arranged her work and study schedules to make the best use of her time, and scheduled time for daily exercise and social activities. |

Social Factors

A LITTLE HELP FROM YOUR FRIENDS

KEY THEME

Social support refers to the resources provided by other people.

KEY QUESTIONS

How has social support been shown to benefit health?

How can relationships and social connections sometimes increase stress?

What gender differences have been found in social support and its effects?

Psychologists have become increasingly aware of the importance that close relationships play in our ability to deal with stressors and, ultimately, in our physical health (Uchino & Birmingham, 2011). Consider the following research evidence:

Analyzing 148 studies that included over 300,000 participants, Julianne Holt-Lundstad and her colleagues (2010) found that people who were socially isolated were twice as likely to die over a given period than people with strong social relationships—a risk factor that is roughly equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

Decades of research have conclusively shown that loneliness, especially chronic loneliness, predicts poorer physical and mental health, higher death rates, and decreased cognitive functioning (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010).

In a study begun in the 1950s, college students rated their parents’ level of love and caring. A half-century later, 87 percent of those who had rated their parents as being “low” in love and caring had been diagnosed with a serious physical disease. In contrast, only 25 percent of those who had rated their parents as being “high” in love and caring had been diagnosed with a serious physical disease (Shaw & others, 2004).

These are just a few of the hundreds of studies exploring how interpersonal relationships influence our health and ability to tolerate stress (Cohen, 2004; Uchino, 2009). To investigate the role played by personal relationships in stress and health, psychologists measure the level of social support—the resources provided by other people in times of need.

social support

The resources provided by other people in times of need.

Decades of psychological research have shown that socially isolated people have poorer health and higher death rates than people who have many social contacts or relationships. In fact, social isolation seems to be as potent a health risk as smoking, alcohol abuse, obesity, or physical inactivity (Holt-Lunstad & others, 2010; Steptoe & others, 2013).

Beyond social isolation, researchers have found that the more diverse your social network, the more pronounced the health benefits (Cohen & Janicki-Deverts, 2009). That is, prospective studies have shown that the people who live longest are those who have more different types of relationships—such as being married; having close relationships with family members, friends, and neighbors; and belonging to social, political, or religious groups (Berkman & Glass, 2000). In fact, researchers have found that people who live in such diverse social networks have:

greater resistance to upper respiratory infections (Cohen, 2005)

lower incidence of stroke and cardiovascular disease among women in a high-risk group (Rutledge & others, 2004, 2008)

lower incidence of dementia and cognitive loss in old age (Desai & others, 2010)

HOW SOCIAL SUPPORT BENEFITS HEALTH

Social support may benefit our health and improve our ability to cope with stressors in several ways (Uchino, 2009). First, the social support of friends and relatives can modify our appraisal of a stressor’s significance, including the degree to which we perceive it as threatening or harmful. Simply knowing that support and assistance are readily available may make the situation seem less threatening.

Second, the presence of supportive others seems to decrease the intensity of physical reactions to a stressor (Uchino & others, 2010). Thus, when faced with a painful medical procedure or some other stressful situation, many people find the presence of a supportive friend to be calming.

Third, social support can influence our health by making us less likely to experience negative emotions (Cohen, 2004). Given the well-established link between chronic negative emotions and poor health, a strong social support network can promote positive moods and emotions, enhance self-esteem, and increase feelings of personal control. In contrast, loneliness and depression are unpleasant emotional states that increase levels of stress hormones and adversely affect immune system functioning (Irwin & Miller, 2007).

The flip side of the coin is that relationships with others can also be a significant source of stress (Rook & others, 2011; Lund & others, 2014). In fact, negative interactions with other people are sometimes more effective at creating psychological distress than positive interactions are at improving well-being (Rafaeli & others, 2008). And, although married people tend to be healthier than unmarried people overall, marital conflict has been shown to have adverse effects on physical health, especially for women (Whisman & others, 2010).

Clearly, the quality of interpersonal relationships is an important determinant of whether those relationships help or hinder our ability to cope with stressful events. When other people are perceived as being judgmental, their presence may increase the individual’s physical reaction to a stressor. In two clever studies, psychologist Karen Allen and her colleagues (1991, 2002) demonstrated that the presence of a favorite dog or cat was more effective than the presence of a spouse or friend in lowering reactivity to a stressor. Why? Perhaps because the pet was perceived as being nonjudgmental, non-evaluative, and unconditionally supportive. Unfortunately, the same is not always true of friends, family members, and partners.

Stress may also increase when well-meaning friends or family members offer unwanted or inappropriate social support. The In Focus box offers some suggestions on how to provide helpful social support and avoid inappropriate support behaviors.

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN THE EFFECTS OF SOCIAL SUPPORT

Who do you turn to when you are in need of help? In general, men tend to rely heavily on a close relationship with their spouse or partner. Women, in contrast, are more likely to list close friends along with their spouse as confidants (Ackerman & others, 2007; Coventry & others, 2004). Because men tend to have a much smaller network of intimate others, they may be particularly vulnerable to social isolation, especially if their spouse dies. That may be one reason that the health benefits of being married are more pronounced for men than for women (Zwicker & DeLongis, 2010).

When stressful events strike, women tend to reach out to one another for support and comfort (Taylor & Master, 2011). For example, Andi’s many friends rallied around her when she returned to Boulder, helping her find a place to live, and bringing food and groceries to her rental cottage. And, rather than face her burned-out home for the first time alone, Andi recruited your author Sandy and a few other close friends to go with her.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that marriage is more beneficial for the health of women than of men?

On the other hand, women can be particularly vulnerable to some of the problematic aspects of social support, for a couple of reasons. First, women are more likely than men to serve as providers of support, which can be a very stressful role (Ekwall & Hallberg, 2007).

Second, women may be more likely to suffer from the stress contagion effect, becoming upset about negative life events that happen to other people whom they care about (Dalgard & others, 2006). Since women tend to have larger and more intimate social networks than men, they have more opportunities to become distressed by what happens to people who are close to them. And women are more likely than men to be upset about negative events that happen to their relatives and friends. In contrast, men are more likely to be distressed only by negative events that happen to their immediate family—their wives and children (Rosenfield & Smith, 2010).

Test your understanding of Individual Factors That Influence the Response to Stress with

.

.

IN FOCUS

A close friend turns to you for help in a time of crisis or personal tragedy. What should you do or say? As we’ve noted in this chapter, appropriate social support can help people weather crises and can significantly reduce the amount of distress that they feel. Inappropriate support, in contrast, may only make matters worse (Uchino, 2009).

Researchers generally agree that there are several broad categories of social support. Three are most commonly studied: emotional, tangible, and informational. Each provides different beneficial functions (Lett & others, 2009).

Emotional support includes expressions of concern, empathy, and positive regard. Tangible support involves direct assistance, such as providing transportation, lending money, or helping with meals, child care, or household tasks. When people offer helpful suggestions, advice, or possible resources, they are providing informational support.

It’s possible that all three kinds of social support might be provided by the same person, such as a relative, spouse, or very close friend. More commonly, we turn to different people for different kinds of support (Masters & others, 2007).

Psychologists have identified several support behaviors that are typically perceived as helpful by people under stress (Goldsmith, 2004; Hobfoll & others, 1992). In a nutshell, you’re most likely to be perceived as helpful if you:

are a good listener and show concern and interest

ask questions that encourage the person under stress to express his or her feelings and emotions

express understanding about why the person is upset

express affection for the person, whether with a warm hug or simply a pat on the arm

are willing to invest time and attention in helping

can help the person with practical tasks, such as housework, transportation, or responsibilities at work or school

Just as important is knowing what not to do or say. Andi in the Prologue story frequently expressed frustration about well-meaning comments that simply made her feel worse. A prime example were statements beginning with the words “At least … ,” as when people said, “Well, your house and all your belongings are destroyed, but at least you’re safe.” As Andi said, “If your sentence starts with ‘at least,’ don’t say it at all!” Here are several behaviors that, however well intentioned, are often perceived as unhelpful:

Giving advice that the person under stress has not requested.

Telling the person, “I know exactly how you feel.” It’s a mistake to think that you have experienced distress identical to what the other person is experiencing.

Nicolas McComber/Getty Images

Nicolas McComber/Getty ImagesTalking about yourself or your own problems.

Minimizing the importance of the person’s problem by saying things like, “Hey, don’t make such a big deal out of it,” “It could be a lot worse,” or “Don’t worry, everything will turn out okay.”

Joking or acting overly cheerful.

Offering your philosophical or religious interpretation of the stressful event by saying things like, “It’s fate,” “It’s God’s will,” or “It’s your karma.”

Making a big deal out of the support and help you do provide, which may make the recipient feel even more anxious or vulnerable. In fact, “invisible support,” in which the recipient isn’t aware of your help, is one of the most effective forms of social support (Bolger & Amarel, 2007; Howland & Simpson, 2010). For example, asking a question in class because you know that a classmate doesn’t understand the material would be an example of invisible support.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that the best way to comfort a stressed-out friend or relative is to give them advice and show them that the problem is not as bad as it seems?

Finally, remember that although social support is helpful, it is not a substitute for counseling or psychotherapy. If a friend seems overwhelmed by problems or emotions, or is having serious difficulty handling the demands of everyday life, you should encourage him or her to seek professional help. Most college campuses have a counseling center or a health clinic that can provide referrals to qualified mental health workers. Sliding fee schedules, based on ability to pay, are usually available. Thus, you can assure the person that cost need not be an obstacle to getting help—or an additional source of stress!