14.2 Fear and Trembling

ANXIETY DISORDERS, POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER, AND OBSESSIVE–COMPULSIVE DISORDER

KEY THEME

Intense anxiety that disrupts normal functioning is an essential feature of the anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

KEY QUESTIONS

How does pathological anxiety differ from normal anxiety?

What characterizes generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder?

What are the phobias, and how have they been explained?

Anxiety is a familiar emotion to all of us—that feeling of tension, apprehension, and worry that often hits during personal crises and everyday conflicts. Although it is unpleasant, anxiety is sometimes helpful. Think of anxiety as your personal, internal alarm system that tells you that something is not quite right. When it alerts you to a realistic threat, anxiety is adaptive and normal. For example, anxiety about your grades may motivate you to study harder.

anxiety

An unpleasant emotional state characterized by physical arousal and feelings of tension, apprehension, and worry.

Anxiety has both physical and mental effects. As your internal alarm system, anxiety puts you on physical alert, preparing you to defensively “fight” or “flee” potential dangers. Anxiety also puts you on mental alert, making you focus your attention squarely on the threatening situation. You become extremely vigilant, scanning the environment for potential threats. When the threat has passed, your alarm system shuts off and you calm down. But even if the problem persists, you can normally put your anxious thoughts aside temporarily and attend to other matters.

In the anxiety disorders, however, the anxiety is maladaptive, disrupting everyday activities, moods, and thought processes. It’s as if you’ve triggered a faulty car alarm that activates at the slightest touch and has a broken “off “ switch.

anxiety disorders

A category of psychological disorders in which extreme anxiety is the main diagnostic feature and causes significant disruptions in the person’s cognitive, behavioral, or interpersonal functioning.

Three features distinguish normal anxiety from pathological anxiety. First, pathological anxiety is irrational. The anxiety is provoked by perceived threats that are exaggerated or nonexistent, and the anxiety response is out of proportion to the actual importance of the situation. Second, pathological anxiety is uncontrollable. The person can’t shut off the alarm reaction, even when he or she knows it’s unrealistic.

And third, pathological anxiety is disruptive. It interferes with relationships, job or academic performance, or everyday activities. In short, pathological anxiety is unreasonably intense, frequent, persistent, and disruptive (Beidel & Stipelman, 2007; Woo & Keatinge, 2008).

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that the less anxiety you have, the better?

As a symptom, anxiety occurs in many different psychological disorders. In the anxiety disorders, however, anxiety is the main symptom, although it is manifested differently in each of the disorders. Other disorders with anxiety as a symptom include posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). In this section, we’ll talk about anxiety disorders, PTSD, and OCD, but we’ll first focus on the anxiety disorders.

Disorders that include anxiety—the anxiety disorders, PTSD, and OCD—are among the most common of all psychological disorders. According to some estimates, they will affect about one in four people in the United States during their lifetimes (Kessler & others, 2005b; McGregor, 2009). Evidence of disabling anxiety has been found in virtually every culture studied, although symptoms may vary from one cultural group to another (Chentsova-Dutton & Tsai, 2007; Good & Hinton, 2009). Most of these disorders are much more common in women than in men (McLean & others, 2011).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

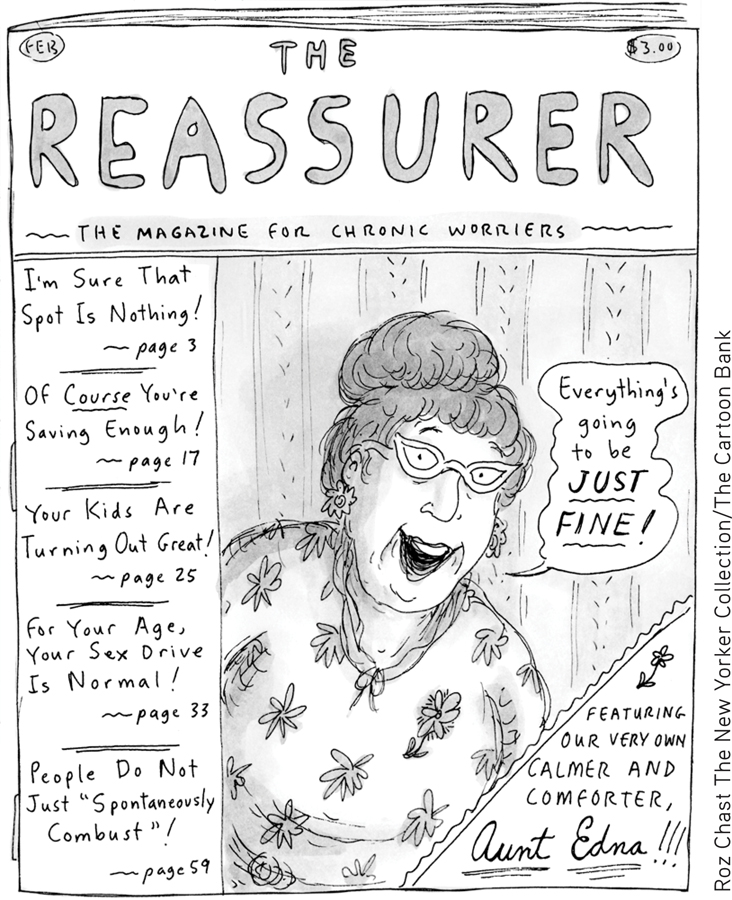

WORRYING ABOUT ANYTHING AND EVERYTHING

Global, persistent, chronic, and excessive apprehension is the main feature of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). People with this disorder are constantly tense and anxious, and their anxiety is pervasive. They feel anxious about a wide range of life circumstances, sometimes with little or no apparent justification (Craske & Waters, 2005; Sanfelippo, 2006). The more issues about which a person worries excessively, the more likely it is that he or she suffers from generalized anxiety disorder (DSM-5, 2013).

generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

An anxiety disorder characterized by excessive, global, and persistent symptoms of anxiety; also called free-floating anxiety.

Normally, anxiety quickly dissipates when a threatening situation is resolved. In generalized anxiety disorder, however, when one source of worry is removed, another quickly moves in to take its place. The anxiety can be attached to virtually any object or to none at all. Because of this, generalized anxiety disorder is sometimes referred to as free-floating anxiety.

EXPLAINING GENERALIZED ANXIETY DISORDER

What causes generalized anxiety disorder? As is true with most psychological disorders, environmental, psychological, and genetic as well as other biological factors are probably involved in GAD (Payne & others, 2014; Stein & Steckler, 2010). For example, a brain that is “wired” for anxiety can give a person a head start toward developing GAD in later life, but problematic relationships and stressful experiences can make the possibility more likely. Signs of problematic anxiety can be evident from a very early age, such as in the example of a child with a very shy temperament who consistently feels overwhelming anxiety in new situations or when separated from his parents. In some cases, such children develop anxiety disorders such as GAD in adulthood (Creswell & O’Connor, 2011; Weems & Silverman, 2008).

Panic Attacks and Panic Disorders

SUDDEN EPISODES OF EXTREME ANXIETY

Generalized anxiety disorder is like the dull ache of a sore tooth—a constant, ongoing sense of uneasiness, distress, and apprehension. In contrast, a panic attack is a sudden episode of extreme anxiety that rapidly escalates in intensity. The most common symptoms of a panic attack are a pounding heart, rapid breathing, breathlessness, and a choking sensation. The person may also sweat, tremble, and experience light-headedness, chills, or hot flashes. Accompanying the intense, escalating surge of physical arousal are feelings of terror and the belief that one is about to die, go crazy, or completely lose control. A panic attack typically peaks within 10 minutes of onset and then gradually subsides. Nevertheless, the physical symptoms of a panic attack are so severe and frightening that it’s not unusual for people to rush to an emergency room, convinced they are having a heart attack, stroke, or seizure (Buccelletti & others, 2013; Craske & Barlow, 2008).

panic attack

A sudden episode of extreme anxiety that rapidly escalates in intensity.

Sometimes panic attacks occur after a stressful experience, such as an injury or illness, or during a stressful period of life, such as while changing jobs or during a period of marital conflict (Moitra & others, 2011). Experiences of bereavement, separation from significant others, and interpersonal loss are among the experiences most often associated with triggering panic attacks (Klauke & others, 2010). In other cases, however, panic attacks seem to come from nowhere.

When panic attacks occur frequently and unexpectedly, the person is said to be suffering from panic disorder. In this disorder, the frequency of panic attacks is highly variable and quite unpredictable. One person may have panic attacks several times a month. Another person may go for months without an attack and then experience panic attacks for several days in a row. Understandably, people with panic disorder are quite apprehensive about when and where the next panic attack will hit (Craske & Waters, 2005; Good & Hinton, 2009).

panic disorder

An anxiety disorder in which the person experiences frequent and unexpected panic attacks.

Some panic disorder sufferers go on to develop agoraphobia. Agoraphobia involves fear of suffering a panic attack or other embarrassing or incapacitating symptoms in a place from which escape would be difficult or impossible (DSM-5, 2013). For example, some agoraphobia sufferers fear falling, getting lost, or becoming incontinent in a public place where help might not be available and escape might be impossible. Crowds, stores, elevators, public transportation, or even traveling in a car may be avoided. Many people with agoraphobia, imprisoned by their fears, never leave their homes.

agoraphobia

An anxiety disorder involving extreme fear of experiencing a panic attack or other embarrassing or incapacitating symptoms in a public situation where escape is impossible and help is unavailable.

Your author Susan treated a number of people with agoraphobia while working in an outpatient clinic for people with panic disorders. For example, Anya, a 32-year-old accountant, experienced infrequent but intense attacks of anxiety and fearfulness. Heart pounding and perspiring heavily, she felt as though she couldn’t breathe. More than once, Anya called an ambulance because she was convinced she was having a heart attack. As her panic attacks increased in frequency and severity, Anya quit her job, fearful that she might have a panic attack while driving to work, riding the elevator to her office, or meeting with clients.

EXPLAINING PANIC DISORDER

People with panic disorder are often hypersensitive to the signs of physical arousal (Schmidt & Keough, 2010; Zvolensky & Smits, 2008). The fluttering heartbeat or momentary dizziness that the average person barely notices signals disaster to the panic-prone. Researchers have suggested that this oversensitivity to physical arousal is one of three important factors in the development of panic disorder. This triple vulnerabilities model of panic states that a biological predisposition toward anxiety, a low sense of control over potentially life-threatening events, and an oversensitivity to physical sensations combine to make a person vulnerable to panic (Bentley & others, 2013; Craske & Barlow, 2008).

People with panic disorder may also be victims of their own illogical thinking. According to the catastrophic cognitions theory, people with panic disorder are not only oversensitive to physical sensations, they also tend to catastrophize the meaning of their experience (Good & Hinton, 2009; Hinton & Hinton, 2009). A few moments of increased heart rate after climbing a flight of stairs is misinterpreted as the warning signs of a heart attack. Such catastrophic misinterpretations simply add to the physiological arousal, creating a vicious circle in which the frightening symptoms intensify.

Syndromes resembling panic disorder have been reported in many cultures (Chentsova-Dutton & Tsai, 2007; Hinton & Hinton, 2009). For example, the Spanish phrase ataque de nervios literally means “attack of nerves.” It’s a disorder reported in many Latin American cultures, in Puerto Rico, and among Latinos in the United States. Ataque de nervios has many symptoms in common with panic disorder—heart palpitations, dizziness, and the fear of dying, going crazy, or losing control. However, the person experiencing ataque de nervios also becomes hysterical. She may scream, swear, strike out at others, and break things. Ataque de nervios typically follows a severe stressor, especially one involving a family member. Funerals, accidents, or family conflicts often trigger such attacks. Because ataque de nervios tends to elicit immediate social support from others, it seems to be a culturally shaped, acceptable way to respond to severe stress.

The Phobias

FEAR AND LOATHING

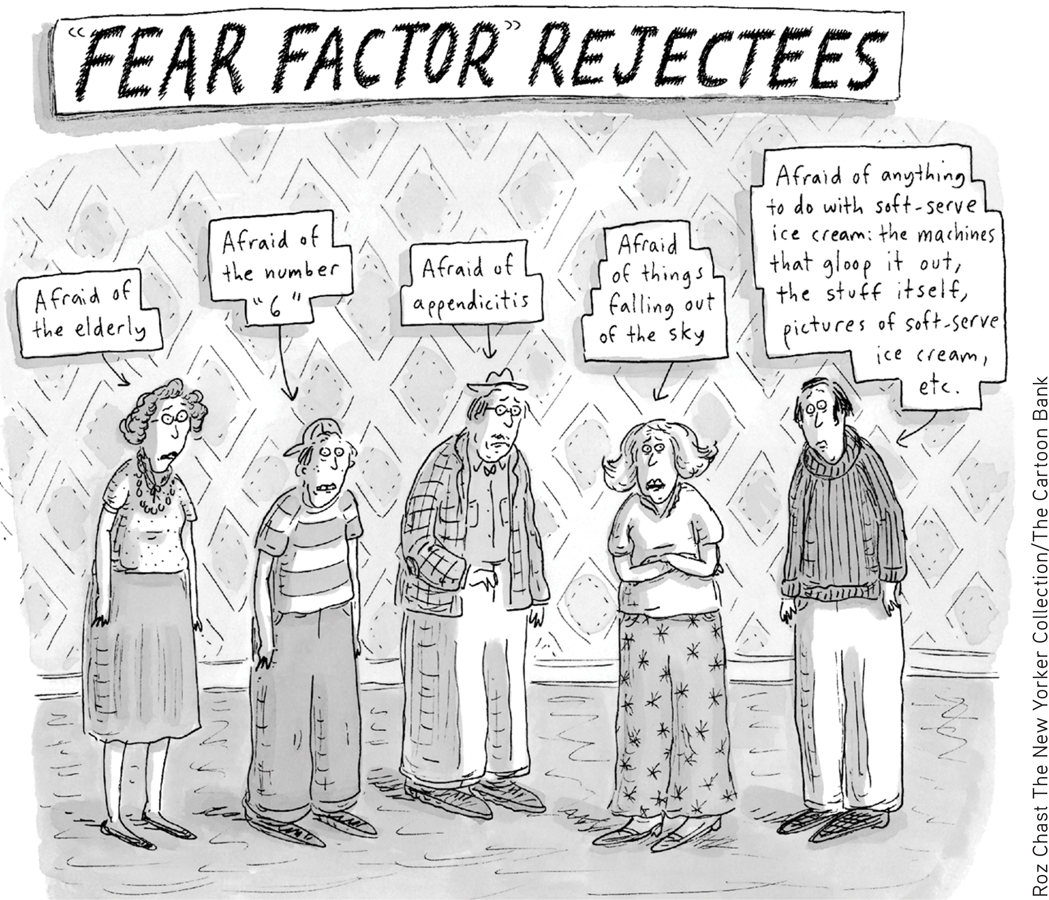

A phobia is a persistent and irrational fear of a specific object, situation, or activity. In the general population, mild irrational fears that don’t significantly interfere with a person’s ability to function are very common. Many people are fearful of certain animals, such as dogs or snakes, or are moderately uncomfortable in particular situations, such as flying in a plane or riding in a glass elevator. Nonetheless, many people cope with such fears without being overwhelmed with anxiety. As long as the fear doesn’t interfere with their daily functioning, they would not be diagnosed with a psychological disorder.

phobia

A persistent and irrational fear of a specific object, situation, or activity.

In comparison, people with specific phobia, formerly called simple phobia, are more than just terrified of a particular object or situation. In some people, encountering the feared situation or object can provoke a full-fledged panic attack. Importantly, the incapacitating terror and anxiety interfere with the person’s ability to function in daily life. Some people with phobias realize that their fears are irrational or excessive, but still will go to great lengths to avoid the feared object or situation. Consider the case of Antonio, who has a phobia of dogs. He works in a pizza parlor, making pizzas and taking orders. He could make more money if he took a job as a delivery person, but he won’t even consider it because he is too afraid he might encounter a dog while making deliveries.

specific phobia

An excessive, intense, and irrational fear of a specific object, situation, or activity that is actively avoided or endured with marked anxiety.

About 13 percent of the general population experiences a specific phobia at some time in their lives (Kessler & others, 2005a). More than twice as many women as men suffer from specific phobia. Occasionally, people have unusual phobias. (See TABLE 14.2.) Oprah Winfrey, for example, has been afraid of chewing gum since she was a child because she was disgusted when her grandmother left used gum around the house. In an interview with Jamie Foxx, she told him: “When I saw you chewing on Oscar night, I freaked out” (O Magazine, 2005). Generally, the objects or situations that produce specific phobias tend to fall into four categories:

Fear of particular situations, such as flying, driving, tunnels, bridges, elevators, crowds, or enclosed places

Fear of features of the natural environment, such as heights, water, thunderstorms, or lightning

Fear of injury or blood, including the fear of injections, needles, and medical or dental procedures

Fear of animals and insects, such as snakes, spiders, dogs, cats, slugs, or bats

Some Unusual Phobias

| Amathophobia | Fear of dust |

| Anemophobia | Fear of wind |

| Aphephobia | Fear of being touched by another person |

| Bibliophobia | Fear of books |

| Catotrophobia | Fear of breaking a mirror |

| Ergophobia | Fear of work or responsibility |

| Erythrophobia | Fear of red objects |

| Gamophobia | Fear of marriage |

| Hypertrichophobia | Fear of growing excessive amounts of body hair |

| Levophobia | Fear of things being on the left side of your body |

| Phobophobia | Fear of acquiring a phobia |

| Phonophobia | Fear of the sound of your own voice |

| Triskaidekaphobia | Fear of the number 13 |

SOCIAL ANXIETY DISORDERFEAR OF BEING JUDGED IN SOCIAL SITUATIONS

A second type of phobia also deserves additional comment. Social anxiety disorder is one of the most common psychological disorders and is more prevalent among women than men (Altemus, 2006; Kessler & others, 2005b). Social anxiety disorder goes well beyond the shyness that everyone sometimes feels at social gatherings. Rather, the person with social anxiety disorder is paralyzed by fear of social situations in which she may be judged or evaluated by others. Eating a meal in public, making small talk at a party, or using a public restroom can be agonizing for the person with social anxiety disorder.

social anxiety disorder

An anxiety disorder involving the extreme and irrational fear of being embarrassed, judged, or scrutinized by others in social situations.

The core of social anxiety disorder seems to be an irrational fear of being judged or critically evaluated by others. Some, but not all, people with social anxiety disorder recognize that their fear is excessive and irrational. Even so, they approach social situations with tremendous dread and anxiety (Kashdan & others, 2013). In severe cases, they may even suffer a panic attack in social situations. When the fear of being judged by others in social situations significantly interferes with daily life, social anxiety disorder may be present (DSM-5, 2013).

As with panic attacks, cultural influences can add some novel twists to social anxiety disorder. Consider the Japanese disorder called taijin kyofusho. Taijin kyofusho usually affects young Japanese males. It has several features in common with social anxiety disorder, including extreme social anxiety and avoidance of social situations. However, the person with taijin kyofusho is not worried about being embarrassed in public. Rather, reflecting the cultural emphasis of concern for others, the person with taijin kyofusho fears that his appearance or smell, facial expression, or body language will offend, insult, or embarrass other people (Iwamasa, 1997; Norasakkunkit & others, 2012).

EXPLAINING PHOBIASLEARNING THEORIES

The development of some phobias can be explained in terms of basic learning principles (Craske & Waters, 2005). Classical conditioning may well be involved in the development of a specific phobia that can be traced back to some sort of traumatic event. In Chapter 5, on learning, we saw how psychologist John Watson classically conditioned “Little Albert” to fear a tame lab rat that had been paired with loud noise. Following the conditioning, the infant’s fear generalized to other furry objects.

More recently, researchers demonstrated the role of classical conditioning in the development of phobias by pairing something new, like an invented cartoon character named Spardi, with something frightening, like a picture of a woman being mugged at knife-point. Participants rated Spardi as more frightening in this circumstance than when the character was paired with something pleasant, like a picture of a sunset (Vriends & others, 2012). In much the same way, your author Sandy’s neighbor Michelle has been extremely phobic of dogs ever since she was bitten by a German shepherd when she was 4 years old. In effect, Michelle developed a conditioned response (fear) to a conditioned stimulus (the German shepherd) that has generalized to similar stimuli—any dog.

Fotosearch

Operant conditioning can also be involved in the avoidance behavior that characterizes phobias. In Michelle’s case, she quickly learned that she could reduce her anxiety and fear by avoiding dogs altogether. To use operant conditioning terms, her operant response of avoiding dogs is negatively reinforced by the relief from anxiety and fear that she experiences.

Observational learning can also be involved in the development of phobias. Some people learn to be phobic of certain objects or situations by observing the fearful reactions of someone else who acts as a model in the situation. The child who observes a parent react with sheer panic to the sight of a spider or mouse may imitate the same behavioral response. People can also develop phobias from observing vivid media accounts of disasters, as when some people become afraid to fly after watching graphic TV coverage of a plane crash.

We also noted in Chapter 5 that humans seem biologically prepared to acquire fears of certain animals or situations, such as snakes or heights, which were survival threats in human evolutionary history (Workman & Reader, 2008).

People also seem to be predisposed to develop phobias toward creatures that arouse disgust, like slugs, maggots, or cockroaches. Instinctively, it seems, many people find such creatures repulsive, possibly because they are associated with disease, infection, or filth. Such phobias may reflect a fear of contamination or infection that is also based on human evolutionary history (Cisler & others, 2007).

John Arnold/Shutterstock

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

ANXIETY AND INTRUSIVE THOUGHTS

KEY THEME

Extreme anxiety and intrusive thoughts are symptoms of both posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obsessive–

KEY QUESTIONS

What is PTSD, and what causes it?

What is obsessive–

compulsive disorder? What are the most common types of obsessions and compulsions?

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a long-lasting disorder that develops in response to an extreme physical or psychological trauma. Extreme traumas are events that produce intense feelings of horror and helplessness, such as a serious physical injury or threat of injury to yourself or to loved ones. Although not classified as an anxiety disorder, some of the same patterns of emotion, cognition, and behavior mark both PTSD and anxiety disorders.

posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

A disorder triggered by exposure to a highly traumatic event which results in recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive memories of the event; avoidance of stimuli and situations associated with the event; negative changes in thoughts, moods, and emotions; and a persistent state of heightened physical arousal.

Originally, PTSD was primarily associated with direct experiences of military combat. Veterans of military conflict in Afghanistan and Iraq, like veterans of earlier wars, have a higher prevalence of PTSD than nonveterans (E. Cohen & others, 2011; Fontana & Rosenheck, 2008). However, it’s now known that PTSD can also develop in survivors of other sorts of extreme traumas, such as natural disasters, physical or sexual assault, random shooting sprees, or terrorist attacks (McNally, 2003). Rescue workers, relief workers, and emergency service personnel can also develop PTSD symptoms (Berger & others, 2012; Eriksson & others, 2001). Simply witnessing the injury or death of others can be sufficiently traumatic for PTSD to occur. And some researchers have documented PTSD symptoms in people who were exposed to trauma in the media, such as graphic images related to terrorism or war on television (Silver & others, 2013).

In any given year, it’s estimated that more than 5 million American adults experience PTSD. There is also a significant gender difference—more than twice as many women as men experience PTSD after exposure to trauma (Olff & others, 2007). Children can also experience the symptoms of PTSD. For example, one study assessed almost 400 children living in a war zone in the Middle East. More than 20 percent of these children had PTSD, while more than three-quarters of them reported at least moderate levels of symptoms of PTSD (Fasfous & others, 2013). Similarly, about 15 months after Hurricane Katrina, over 60 percent of children in New Orleans had at least mild levels of PTSD symptoms (Langley & others, 2014).

Four core clusters of symptoms characterize PTSD (DSM-5, 2013). First, the person frequently recalls the event, replaying it in his mind. Such recollections are often intrusive, meaning that they are unwanted and interfere with normal thoughts. Recollections can even be triggered by unrelated events. After the Boston Marathon bombings in 2013, almost 40 percent of a sample of military veterans in Boston who already suffered from PTSD reported increased emotional distress (Miller & others, 2013). Second, the person avoids stimuli or situations that tend to trigger memories of the experience. Third, he may experience negative alterations in thinking, moods, and emotions. He may feel alienated from others, blame himself or others for the traumatic event, and feel a persistent sense of guilt, fear, or anger. Often, the person loses interest in relationships or previously enjoyed activities. Some people are unable to recall key features of the traumatic event. Fourth, the person experiences increased physical arousal. He may be easily startled, experience sleep disturbances, have problems concentrating and remembering, and be prone to irritability or angry outbursts (DSM-5, 2013).

Posttraumatic stress disorder is somewhat unusual in that the source of the disorder is the traumatic event itself, rather than a cause that lies within the individual. Even well-adjusted and psychologically healthy people may develop PTSD when exposed to an extremely traumatic event (Ozer & others, 2003). Among Vietnam veterans in the United States, for example, exposure to combat and involvement in actions that harmed civilians or prisoners of war played a bigger role in the development of PTSD than a soldier’s pre-existing psychological vulnerability (Dohrenwend & others, 2013).

Terrorist attacks, because of their suddenness and intensity, are particularly likely to produce posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors, rescue workers, and observers (Neria & others, 2011). For example, four years after the bombing of the Murrah Building in Oklahoma City, more than a third of the survivors suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder. Almost all the survivors had some PTSD symptoms, such as flashbacks, nightmares, intrusive thoughts, and anxiety (North & others, 1999). Seven years after the bombing, more than a quarter still had PTSD (North & others, 2011). Similarly, five years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, more than 11 percent of rescue and recovery workers met formal criteria for PTSD—a rate comparable to that of soldiers returning from active duty in Iraq and Afghanistan (Stellman & others, 2008). Among people who had directly witnessed the attacks, over 16 percent had PTSD symptoms four years after the attacks (Farfel & others, 2008; Jayasinghe & others, 2008).

However, it’s also important to note that no stressor, no matter how extreme, produces posttraumatic stress disorder in everyone. Why is it that some people develop PTSD while others don’t? Several factors influence the likelihood of developing posttraumatic stress disorder. First, there is evidence that a vulnerability to PTSD can be inherited (Wilker & Kolassa, 2013). Second, people with a personal or family history of psychological disorders are more likely to develop PTSD when exposed to an extreme trauma (Amstadter & others, 2009; Koenen & others, 2008). Third, the magnitude of the trauma plays an important role. More extreme stressors are more likely to produce PTSD. Finally, when people undergo multiple traumas, the incidence of PTSD can be quite high.

OBSESSIVE–COMPULSIVE DISORDERCHECKING IT AGAIN … AND AGAIN

When you leave your home, you probably check to make sure all the doors are locked. You may even double-check just to be on the safe side. But once you’re confident that the door is locked, you don’t think about it again. Some people use the term “obsessive–

But now imagine you’ve checked the door 30 times. Yet you’re still not quite sure that the door is really locked. You know the feeling is irrational, but you feel compelled to check again and again. Imagine you’ve also had to repeatedly check that the coffeepot was unplugged, that the stove was turned off, and so forth. Finally, imagine that you got only two blocks away from home before you felt compelled to turn back and check again—because you still were not certain.

Sound agonizing? This is the psychological world of the person who suffers from one form of obsessive–

obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD)

Disorder characterized by the presence of intrusive, repetitive, and unwanted thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive behaviors or mental acts that an individual feels driven to perform (compulsions).

Obsessions are repeated, intrusive, uncontrollable thoughts or mental images that cause the person great anxiety and distress. Obsessions are not the same as everyday worries. Normal worries typically have some sort of factual basis, even if they’re somewhat exaggerated. In contrast, obsessions have little or no basis in reality and are often extremely far-fetched. One common obsession is an irrational fear of dirt, germs, and other forms of contamination. Another common theme is pathological doubt about having accomplished a simple task, such as shutting off appliances (Antony & others, 2007; Renshaw & others, 2010).

obsessions

Repeated, intrusive, and uncontrollable irrational thoughts or mental images that cause extreme anxiety and distress.

A compulsion is a repetitive behavior that a person feels driven to perform. Typically, compulsions are ritual behaviors that must be carried out in a certain pattern or sequence. Compulsions may be overt physical behaviors, such as repeatedly washing your hands, checking doors or windows, or entering and reentering a doorway until you walk through exactly in the middle. Or they may be covert mental behaviors, such as counting or reciting certain phrases to yourself. But note that the person does not compulsively wash his hands because he enjoys being clean. Rather, he washes his hands because to not do so causes extreme anxiety. If the person tries to resist performing the ritual, unbearable tension, anxiety, and distress result (Mathews, 2009).

compulsions

Repetitive behaviors or mental acts that a person feels driven to perform in order to prevent or reduce anxiety and distress, or to prevent a dreaded event or situation.

Obsessions and compulsions tend to fall into a limited number of categories. About three-fourths of obsessive–

The Most Common Obsessions and Compulsions

| Obsession | Description |

|---|---|

| Contamination | Irrational fear of contamination by dirt, germs, or other toxic substances. Typically accompanied by cleaning or washing compulsion. |

| Pathological doubt | Feeling of uncertainty about having accomplished a simple task. Recurring fear that you have inadvertently harmed someone or violated a law. Typically accompanied by checking compulsion. |

| Violent or sexual thoughts | Fear that you have harmed or will harm another person or have engaged or will engage in some sort of unacceptable behavior. May take the form of intrusive mental images or impulses. |

| Compulsion | Description |

| Washing | Urge to repeatedly wash yourself or clean your surroundings. Cleaning or washing may involve an elaborate, lengthy ritual. Often linked with contamination obsession. |

| Checking | Checking repeatedly to make sure that a simple task has been accomplished. Typically occurs in association with pathological doubt. Checking rituals may take hours. |

| Counting | Need to engage in certain behaviors a specific number of times or to count to a certain number before performing some action or task. |

| Symmetry and precision | Need for objects or actions to be perfectly symmetrical or in an exact order or position. Need to do or undo certain actions in an exact fashion. |

| Source: From Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 15, Rasmussen, Steven A.; & Eisen, Jane L., The epidemiology and clinical features of obsessive– |

|

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is is true that people who are perfectionists probably have obsessive-compulsive disorder?

Many people with obsessive–

People may experience either obsessions or compulsions. More commonly, obsessions and compulsions are both present. Often, the obsessions and compulsions are linked in some way. For example, a man who was obsessed with the idea that he might have lost an important document felt compelled to pick up every scrap of paper he saw on the street and in other public places.

Other compulsions bear little logical relationship to the feared consequences. For instance, a woman believed that if she didn’t get dressed according to a strict pattern, her husband would die in an automobile accident. In all cases, people with obsessive–

Interestingly, obsessions and compulsions take a similar shape in different cultures around the world. However, the content of the obsessions and compulsions tends to mirror the particular culture’s concerns and beliefs. In the United States, compulsive washers are typically preoccupied with obsessional fears of germs and infection. But in rural Nigeria and rural India, compulsive washers are more likely to have obsessional concerns about religious purity rather than germs (Rapoport, 1989; Rego, 2009).

EXPLAINING OBSESSIVE–COMPULSIVE DISORDER

Although the causes of obsessive–

In addition, obsessive–

The anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and obsessive-compulsive disorders are summarized in TABLE 14.4.

Disorders Involving Intense Anxiety

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder |

|---|

| • Persistent, chronic, unreasonable worry and anxiety • General symptoms of anxiety, including persistent physical arousal |

| Panic Disorder |

| • Frequent and unexpected panic attacks, with no specific or identifiable trigger |

| Phobias |

| • Intense anxiety or panic attack triggered by a specific object or situation • Persistent avoidance of feared object or situation |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) |

| • Anxiety triggered by intrusive, recurrent memories of a highly traumatic experience |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) |

| • Anxiety caused by uncontrollable, persistent, recurring thoughts (obsessions) and/or urges to perform certain actions (compulsions) |

CONCEPT REVIEW 14.1

Anxiety, Posttraumatic Stress, and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders

Fill in the blank next to each example below with one of the following disorders: generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, specific phobia, social anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or obsessive–

Question 14.1

| 1. | Esperanza had just entered the lobby of the World Trade Center in New York City when the building was hit by a jetliner on 9/11. Years later, she has frequent headaches and is awakened several times each week by horrifying nightmares of bodies falling from the sky. She dreads the sounds of sirens or planes overhead, and cannot stop thinking about the horrifying sights she saw as she ran from the burning building. |

Question 14.2

| 2. | Alayna worries about everything and can never relax. She is very jumpy, has trouble sleeping at night, and has a poor appetite. For the last few months, her anxiety has become so extreme that she is unable to concentrate at work, and she is in danger of losing her job. |

Question 14.3

| 3. | Ever since going through a very painful divorce, Kayla has experienced a number of terrifying “spells” that seem to come out of nowhere. Her heart suddenly starts to pound, she begins to sweat and tremble, and she has trouble breathing. |

Question 14.4

| 4. | Carl cannot bear to be in small, enclosed places, such as elevators, and goes to great lengths to avoid them. Recently he turned down a high-paying job with an air-conditioning repair company because it involved working in crawl spaces. |

Question 14.5

| 5. | Harry disinfects his shoes, clothing, floor, and doorknobs with bleach several times a day. Nevertheless, he is tormented by worries that his apartment may be contaminated by germs from outside. He doesn’t allow anyone to come into his apartment for fear they will contaminate his furniture and belongings. |

Question 14.6

| 6. | Kathy is so painfully shy that she dropped out of college rather than take a public-speaking class. Although she is very bright and hardworking, she is unemployed because she cannot bring herself to go to a job interview. |

Test your understanding of Anxiety Disorders with

.

.