14.3 Depressive and Bipolar Disorders

DISORDERED MOODS AND EMOTIONS

KEY THEME

In the depressive and the bipolar disorders, disturbed emotions cause psychological distress and impair daily functioning.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the symptoms and course of major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, bipolar disorder, and cyclothymic disorder?

How prevalent are depressive and bipolar disorders?

What factors contribute to the development of depressive and bipolar disorders?

Let’s face it, we all have our ups and downs. When things are going well, we feel cheerful and optimistic. When events take a more negative turn, our mood can sour. We feel miserable and pessimistic. Either way, the intensity and duration of our moods are usually in proportion to the events going on in our lives. That’s completely normal.

In the depressive disorders and the bipolar and related disorders, however, emotions violate the criteria of normal moods. In quality, intensity, and duration, a person’s emotional state does not seem to reflect what’s going on in his or her life. A person may feel a pervasive sadness despite the best of circumstances. Or a person may be extremely energetic and overconfident with no apparent justification. These mood changes persist much longer than the normal fluctuations in moods that we all experience.

Because disturbed moods and emotions are core symptoms in both the depressive and bipolar disorders, they are sometimes called mood disorders or affective disorders. The word “affect” is synonymous with “emotion” or “feelings.” In DSM-5, depressive disorders and bipolar disorders are given their own distinct categories rather than grouped together. In this section, we’ll look at depressive disorders first and then turn to bipolar disorders.

Major Depressive Disorder

MORE THAN ORDINARY SADNESS

The intense psychological pain of major depressive disorder is hard to convey to those who have never experienced it. In his book Darkness Visible, best-selling author William Styron (1990) described his struggle with major depressive disorder in this way:

All sense of hope had vanished, along with the idea of a futurity; my brain, in thrall to its outlaw hormones, had become less an organ of thought than an instrument registering, minute by minute, varying degrees of its own suffering. The mornings themselves were becoming bad now as I wandered about lethargic, following my synthetic sleep, but afternoons were still the worst, beginning at about three o’clock, when I’d feel the horror, like some poisonous fogbank, roll in upon my mind, forcing me into bed. There I would lie for as long as six hours, stuporous and virtually paralyzed, gazing at the ceiling. …

major depressive disorder

A mood disorder characterized by extreme and persistent feelings of despondency, worthlessness, and hopelessness, causing impaired emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and physical functioning.

THE SYMPTOMS OF MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER

The Styron passage gives you a feeling for how the symptoms of depression affect the whole person—emotionally, cognitively, behaviorally, and physically. Take a few minutes to study FIGURE 14.3 which summarizes the common symptoms of major depressive disorder. Depression is also often accompanied by the physical symptoms of anxiety (Andover & others, 2011). Some depressed people experience a sense of physical restlessness or nervousness, demonstrated by fidgeting or aimless pacing.

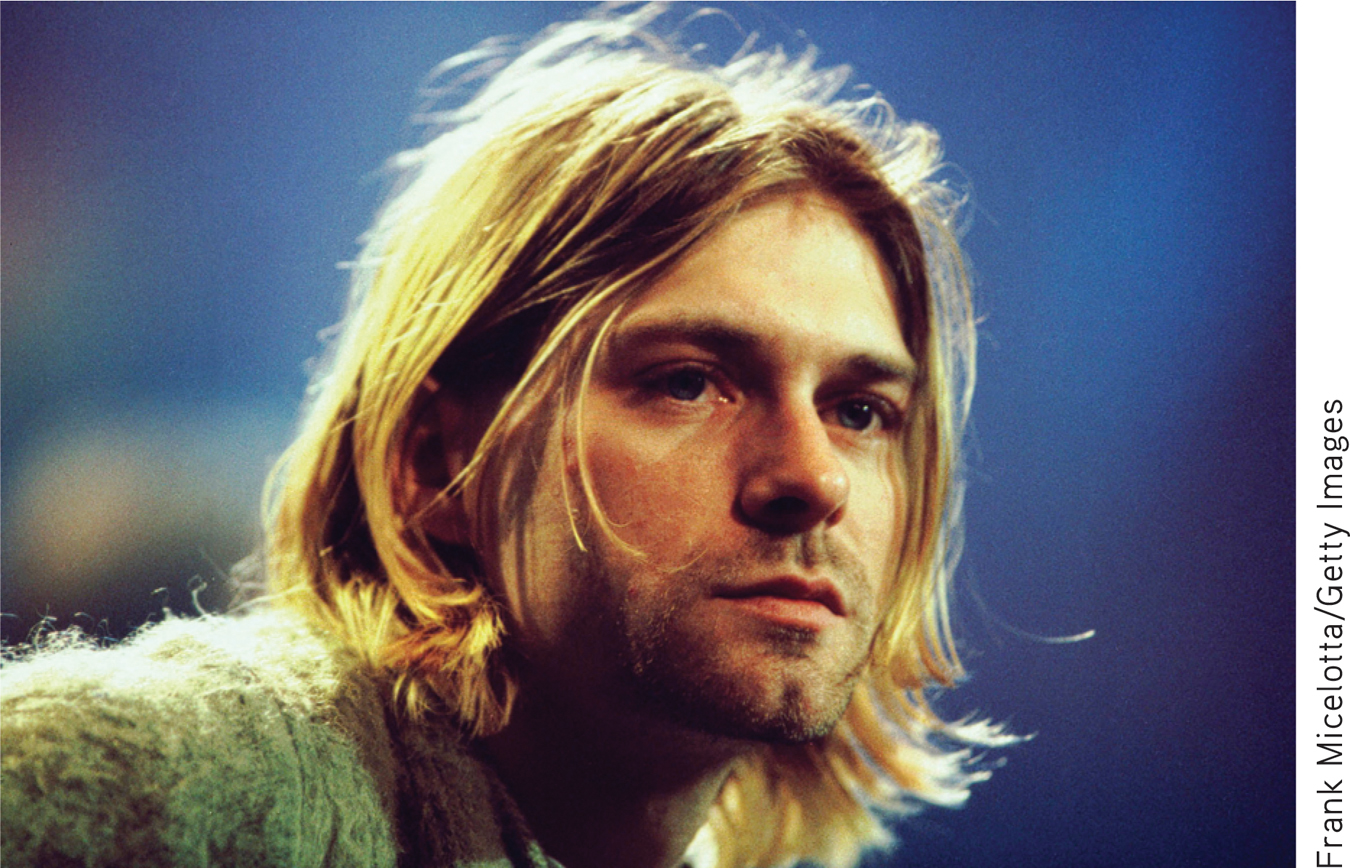

Suicide is always a potential risk in major depressive disorder (Brådvik & Berglund, 2010). Thoughts become globally pessimistic and negative about the self, the world, and the future (Beck & others, 1979; Possel & Black, 2014). This pervasive negativity and pessimism are often manifested in suicidal thoughts or a preoccupation with death. Approximately 10 percent of those suffering from major depressive disorder attempt suicide (McGirr & others, 2007). Grammy award–

Abnormal sleep patterns are another hallmark of major depressive disorder. The amount of time spent in nondreaming, deeply relaxed sleep is greatly reduced or absent (see Chapter 4). Rather than the usual 90-minute cycles of dreaming, the person experiences sporadic REM periods of varying lengths. Spontaneous awakenings occur repeatedly during the night. Very commonly, the depressed person awakens at 3:00 or 4:00 a.m., then cannot get back to sleep, despite feeling exhausted. Less commonly, some depressed people sleep excessively, sometimes as much as 18 hours a day.

To be diagnosed with major depressive disorder, a person must display most of the symptoms described for two weeks or longer (DSM-5, 2013). In many cases, there doesn’t seem to be any external reason for the persistent feeling of depression. In other cases, a person’s downward emotional spiral has been triggered by a negative life event, stressful situation, or chronic stress (Gutman & Nemeroff, 2011).

One significant negative event deserves special mention: the death of a loved one. Previous editions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual stated that depression-like symptoms that might accompany grieving did not qualify as major depression unless those symptoms persisted for two months, rather than two weeks. DSM-5 removes that special treatment for bereavement, based on the reasoning that bereavement is like any other psychosocial event that might trigger a depressive episode. While it is normal to feel a sense of loss and deep sadness when a close friend or family member dies, feelings of worthlessness, self-loathing, and the inability to anticipate happiness or pleasure may indicate that major depressive disorder may be present (DSM-5, 2013).

Although major depressive disorder can occur at any time, some people experience symptoms that intensify at certain times of the year. For people with seasonal affective disorder (SAD), repeated episodes of major depressive disorder are as predictable as the changing seasons, especially the onset of autumn and winter when there is the least amount of sunlight. Seasonal affective disorder is more common among women and among people who live in the northern latitudes (Partonen & Pandi-Perumal, 2010).

seasonal affective disorder (SAD)

A mood disorder in which episodes of depression typically occur during the fall and winter and subside during the spring and summer.

Some people experience a chronic form of depression called persistent depressive disorder that is often less severe than major depressive disorder. Persistent depressive disorder may develop after some stressful event or trauma, such as the death of a parent in childhood (DSM-5, 2013). Although the person functions adequately, she has a chronic case of “the blues” that can continue for years.

persistent depressive disorder

A disorder involving chronic feelings of depression that is often less severe than major depressive disorder.

THE PREVALENCE AND COURSE OF MAJOR DEPRESSIVE DISORDER

Major depressive disorder is often called “the common cold” of psychological disorders, and for good reason: It is among the most prevalent psychological disorders. In any given year, about 7 percent of Americans are affected by major depressive disorder (Kessler & others, 2005b). In terms of lifetime prevalence, many researchers have estimated that about 15 percent of Americans will be affected by major depressive disorder at some point in their lives. However, some researchers suspect that number is too low. In a longitudinal study following more than 800 people for 30 years—from childhood through adulthood—about half of the sample experienced an episode of major depressive disorder at some point (Rohde & others, 2013). In this study, the typical length of an episode was 11 weeks.

Women are about twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with major depressive disorder (Hyde & others, 2008). Why the striking gender difference in the prevalence of major depressive disorder? Research by psychologist Susan Nolen-Hoeksema (2001, 2003) suggests that women are more vulnerable to depression because they experience a greater degree of chronic stress in daily life combined with a lesser sense of personal control than men. Women are also more prone to dwell on their problems, adding to the sense of low mastery and chronic strain in their lives. The interaction of these factors creates a vicious circle that intensifies and perpetuates depressed feelings in women (Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2009; Nolen-Hoeksema & others, 2007).

Many people who experience major depressive disorder try to cope with the symptoms without seeking professional help (Edlund & others, 2008; Farmer & others, 2012). Left untreated, the symptoms of major depressive disorder can easily last six months or longer. When not treated, depression may become a recurring mental disorder that becomes progressively more severe. More than half of all people who have been through one episode of major depressive disorder can expect a relapse, usually within two years. With each recurrence, the symptoms tend to increase in severity and the time between major depression episodes decreases (Hammen, 2005; Roca & others, 2011). However, it’s important to note that several effective treatments for depression are available. We will describe many of these treatments in Chapter 15.

Bipolar Disorder

AN EMOTIONAL ROLLER COASTER

Years ago, your author Susan worked as a therapist in a community mental health center. She had been treating a client, a man in his fifties named Henry, who was experiencing symptoms of depression. After several months of appointments, he failed to show up for two weekly appointments in a row. When he returned, he was buoyant. He walked quickly with a bounce to his step, and greeted everyone in the waiting room and at the front desk as if they were old friends. Henry entered Susan’s office grinning, his eyes wild.

Henry’s new mood was not just a decrease in his symptoms of depression. It was a swing in the opposite direction. Henry excitedly told Susan that he had quit his job as an engineer at a small radio station and was putting his savings into an investment scheme that involved medical equipment. He soon changed topics. “I won’t be here next week because I’m going to Mexico! I’m staying at a famous resort in Tulum!” He explained that he would connect with Hollywood stars there, and would soon be working on a movie project, maybe as a producer. Henry then told Susan that he was going to be hired soon as a primetime DJ at the biggest radio station in town.

Henry spoke loudly and so rapidly that his words often got tangled up with each other. His arms and legs looked as if they were about to get tangled up, too—Henry was in constant motion. His grinning, rapid-fire speech was punctuated with grand, sweeping gestures and exaggerated facial expressions. Before Susan could get a word in edgewise and long before the scheduled end of the therapy session, Henry left, despite Susan’s efforts to detain him, explaining that he had to go shopping for new hunting gear.

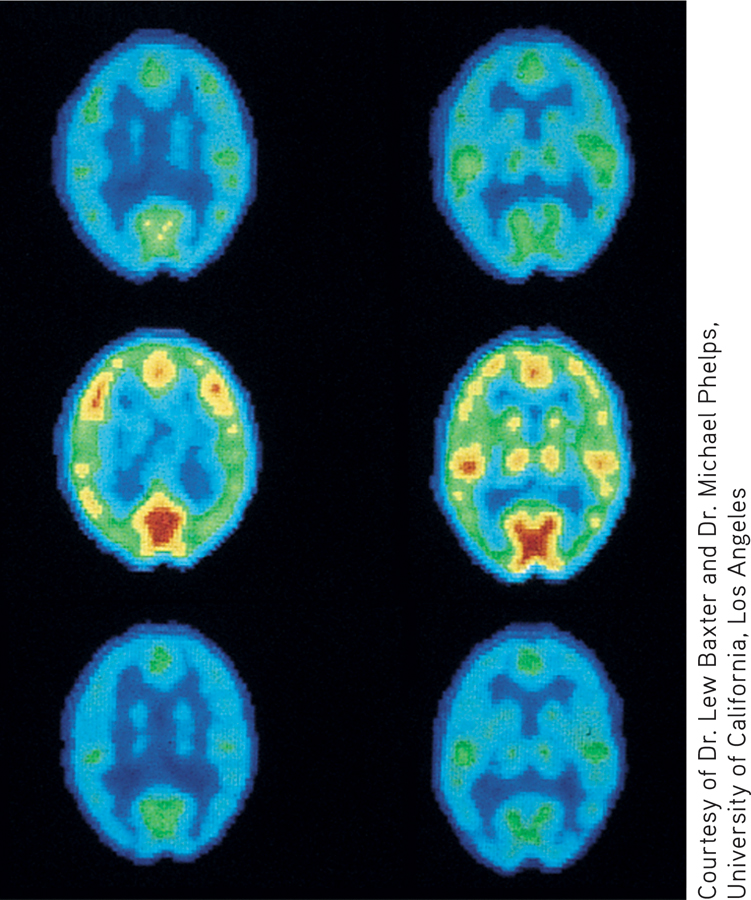

Courtesy of Dr. Lew Baxter and Dr. Michael Phelps, University of California, Los Angeles

THE SYMPTOMS OF BIPOLAR DISORDER

Henry displayed classic symptoms of the mental disorder that used to be called manic depression and is today called bipolar disorder. In contrast to major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder almost always involves abnormal moods at both ends of the emotional spectrum. In most cases of bipolar disorder, the person experiences extreme mood swings. Episodes of incapacitating depression alternate with shorter periods of extreme euphoria, called manic episodes. For the vast majority of people with bipolar disorder, a manic episode immediately precedes or follows a bout with major depressive disorder. However, a small percentage of people with bipolar disorder experience only manic episodes (DSM-5, 2013).

bipolar disorder

A mood disorder involving periods of incapacitating depression alternating with periods of extreme euphoria and excitement; formerly called manic depression.

manic episode

A sudden, rapidly escalating emotional state characterized by extreme euphoria, excitement, physical energy, and rapid thoughts and speech.

Many people use the term “manic” informally to describe people who are in a more energetic mood than normal. But a true manic episode is much more extreme than what we often mean in casual conversation. Manic episodes typically begin suddenly, and symptoms escalate rapidly. During a manic episode, people are uncharacteristically euphoric, expansive, and excited for several days or longer. Although they sleep very little, they have boundless energy. The person’s self-esteem is wildly inflated, and he exudes supreme self-confidence. Often, he has grandiose plans for obtaining wealth, power, and fame (Carlson & Meyer, 2006; Miklowitz, 2008). Sometimes the grandiose ideas represent delusional, or false, beliefs. Henry’s belief that he would make movies with Hollywood stars whom he would meet in Mexico was delusional.

Henry’s fast-forward speech was loud and virtually impossible to interrupt. During a manic episode, words are spoken so rapidly, they’re often slurred as the person tries to keep up with his own thought processes. The manic person feels as if his thoughts are racing along at warp factor 10. Attention is easily distracted by virtually anything, triggering a flight of ideas, in which thoughts rapidly and loosely shift from topic to topic.

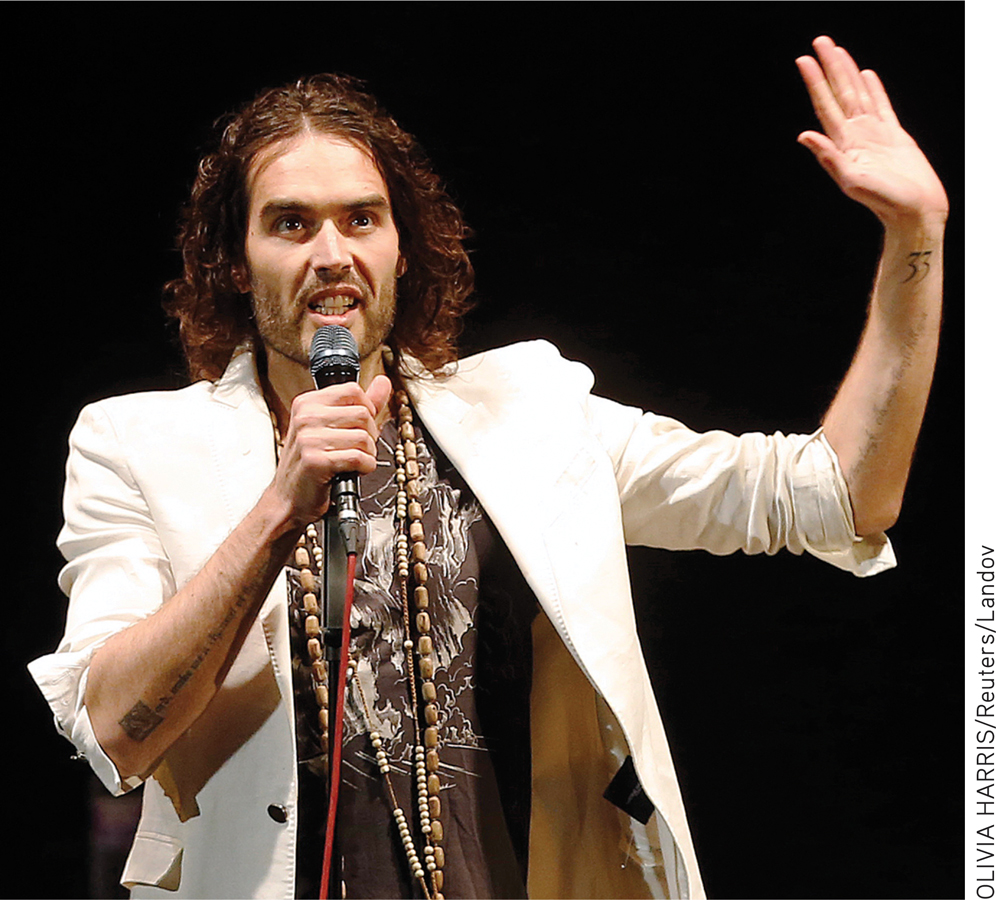

Not surprisingly, the ability to function during a manic episode is severely impaired. Hospitalization is usually required, partly to protect people from the potential consequences of their inappropriate decisions and behaviors. During manic episodes, people can also run up a mountain of bills, disappear for weeks at a time, become sexually promiscuous, or commit illegal acts. Very commonly, the person becomes agitated or verbally abusive when others question her grandiose claims (Miklowitz & Johnson, 2007).

Some people experience a milder but chronic form of bipolar disorder called cyclothymic disorder. In cyclothymic disorder, people experience moderate but frequent mood swings for two years or longer. These mood swings are not severe enough to qualify as either bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder. Often, people with cyclothymic disorder are perceived as being extremely moody, unpredictable, and inconsistent.

cyclothymic disorder

(sie-klo-THY-mick) A mood disorder characterized by moderate but frequent mood swings that are not severe enough to qualify as bipolar disorder.

THE PREVALENCE AND COURSE OF BIPOLAR DISORDER

As in Henry’s case, the onset of bipolar disorder typically occurs in the person’s early 20s. The extreme mood swings of bipolar disorder tend to start and stop much more abruptly than the mood changes of major depressive disorder. And while an episode of major depression can easily last for six months or longer, the manic and depressive episodes of bipolar disorder tend to be much shorter—lasting anywhere from a few days to a couple of months (Fagiolini & others, 2013; Solomon & others, 2010). But contrary to what many people think, the cycling between manic and depressive episodes does not occur in minutes, or even hours.

Bipolar disorder is far less common than major depressive disorder. Unlike major depressive disorder, there are no differences between the sexes in the rate at which bipolar disorder occurs. For both men and women, the lifetime risk of developing bipolar disorder is about 1 percent (Merikangas & others, 2007). Bipolar disorder is rarely diagnosed in childhood. Some evidence suggests that children who display unusually unstable moods are more likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder in adulthood (Blader & Carlson, 2008).

In the vast majority of cases, bipolar disorder is a recurring mental disorder (Jones & Tarrier, 2005). A small percentage of people with bipolar disorder display rapid cycling, experiencing four or more manic or depressive episodes every year (Marneros & Goodwin, 2005). More commonly, bipolar disorder tends to recur every couple of years. Often, bipolar disorder recurs when the individual stops taking lithium, a medication that helps control the disorder. Susan later learned that this was what had happened with Henry.

Explaining Depressive Disorders and Bipolar Disorders

Multiple factors appear to be involved in the development of depressive and bipolar disorders. First, family, twin, and adoption studies suggest that some people inherit a genetic predisposition, or a greater vulnerability, to depressive and bipolar disorders (Kendler & others, 2006; Levinson, 2009; Smoller & Finn, 2003). Researchers have consistently found that both major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder, like most psychological disorders, tend to run in families, although bipolar disorder has much stronger genetic roots than major depressive disorder (Moore & others, 2013; Sullivan & others, 2012). Personality characteristics associated with these disorders have also been found to have a genetic component, even in children who do not share a parent’s diagnosis (Murray & others, 2007). For example, nondepressed children of parents with depressive disorders show the kind of biased thinking and the patterns of brain activity often seen in people who are depressed (Gotlib & others, 2014).

Robert Capa/Magnum Photos

CSU Archives/Everett Collection

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that many psychological disorders run in families?

A second factor that has been implicated in the development of depressive and bipolar disorders is differences in the activation of structures in the brain. For example, one study found that people who were depressed showed increased activation in certain parts of the brain when trying to get rid of negative words in their working memory (Foland-Ross & others, 2013). People who were not depressed showed similar activation, an indication of effort, when getting rid of positive words.

Another important factor is disruptions in brain chemistry. Since the 1960s, several medications, called antidepressants, have been developed to treat major depressive disorder. Some researchers believe that increased levels in the brain of some neurotransmitters, such as norepinephrine and serotonin, accompany an improvement in the symptoms of depression among people taking antidepressants. Antidepressant medications will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 15.

Abnormal levels of another neurotransmitter may also be involved in bipolar disorder. For decades, it’s been known that the drug lithium effectively alleviates symptoms of both mania and depression. Apparently, lithium regulates the availability of a neurotransmitter called glutamate, which acts as an excitatory neurotransmitter in many brain areas (Dixon & Hokin, 1998). By normalizing glutamate levels, lithium helps prevent both the excesses that may cause mania and the deficits that may cause depression.

Stress is also implicated in the development of depressive and bipolar disorders. First, major depressive disorder and chronic stress lead to remarkably similar changes in the neurochemistry of the brain (Hill & others, 2012). Second, major depressive disorder is often triggered by traumatic and stressful events (Gutman & Nemeroff, 2011). Exposure to recent stressful events is one of the best predictors of episodes of major depressive disorder. This is especially true for people who have experienced previous episodes of depression and who have a family history of depressive disorders or mood disorders. But even in people with no family or personal history of either disorder, chronic stress can produce major depressive disorder (Muscatell & others, 2009).

Finally, recent research has uncovered some intriguing links between cigarette smoking and the development of major depressive disorder and other psychological disorders (Munafo & others, 2008). We explore the connection between cigarette smoking and mental illness in the Critical Thinking box “Does Smoking Cause Major Depressive Disorder and Other Psychological Disorders?”

In summary, considerable evidence points to the role of genetic factors, biochemical factors, and stressful life events in the development of both depressive disorders and bipolar disorders (Feliciano & Arean, 2007). However, exactly how these factors interact to cause these disorders is still being investigated. TABLE 14.5 summarizes the symptoms of the most important depressive disorders and bipolar disorders.

Depressive Disorders and Bipolar Disorders

| Major Depressive Disorder |

|---|

| • Loss of interest or pleasure in almost all activities • Despondent mood; feelings of emptiness, worthlessness, or excessive guilt • Preoccupation with death or suicidal thoughts • Difficulty sleeping or excessive sleeping • Diminished ability to think, concentrate, or make decisions • Diminished appetite and significant weight loss |

| Persistent Depressive Disorder |

| • Chronic depressed feelings that are often less severe than those that accompany major depressive disorder |

| Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) |

| • Recurring episodes of depression that follow a seasonal pattern, typically occurring in the fall and winter months and subsiding in the spring and summer months |

| Bipolar Disorder |

| • One or more manic episodes characterized by euphoria, high energy, grandiose ideas, flight of ideas, inappropriate self-confidence, and decreased need for sleep • Usually one or more major depressive episodes • In some cases, may rapidly alternate between symptoms of mania and major depressive disorder |

| Cyclothymic Disorder |

| • Moderate, recurring mood swings that are not severe enough to qualify as major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder |

CRITICAL THINKING

Does Smoking Cause Major Depressive Disorder and Other Psychological Disorders?

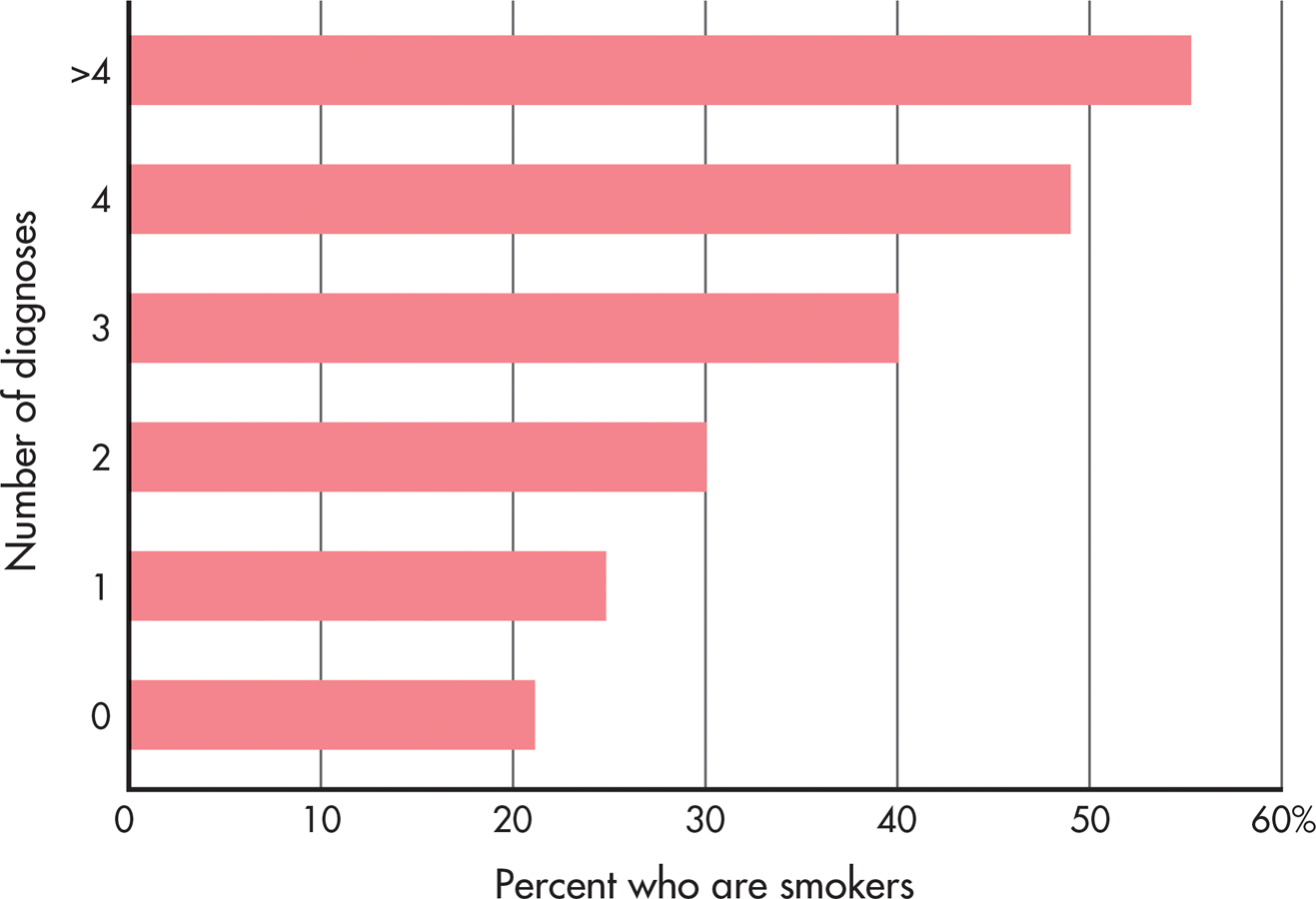

Are people with a mental disorder more likely to smoke than other people? Researcher Karen Lasser and her colleagues (2000) assessed smoking rates in American adults with and without psychological disorders. Lasser found that people with mental illness are twice as likely to smoke cigarettes as people with no mental illness. Here are some of the specific findings from Lasser’s study:

Forty-one percent of individuals with a current psychological disorder are smokers, as compared to 22 percent of people who have never been diagnosed with a mental disorder.

People with a psychological disorder are more likely to be heavy smokers, consuming a pack of cigarettes per day or more.

People who have been diagnosed with many psychological disorders have higher rates of smoking than people with fewer mental disorders (see the graph below).

Forty-four percent of all cigarettes smoked in the United States are consumed by people with one or more psychological disorders.

What can account for the correlation between smoking and psychological disorders? Subjectively, smokers often report that they experience better attention and concentration, increased energy, lower anxiety, and greater calm after smoking, effects that are probably due to the nicotine in tobacco. So, one possible explanation is that people with a mental illness smoke as a form of self-medication. Notice that this explanation assumes that mental illness causes people to smoke.

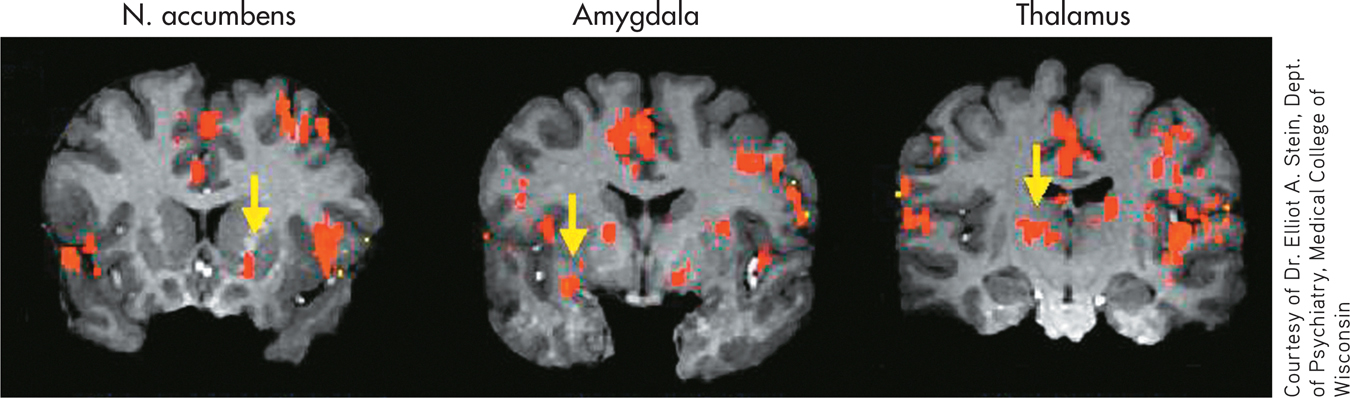

Nicotine, of course, is a powerful psychoactive drug. It triggers the release of dopamine and stimulates key brain structures involved in producing rewarding sensations, including the thalamus, the amygdala, and the nucleus accumbens (Berrendero & others, 2010; Le Foll & Goldberg, 2007; Stein & others, 1998). Nicotine receptors on different neurons also regulate the release of other important neurotransmitters, including serotonin, acetylcholine, GABA, and glutamate (McGehee & others, 2007). In other words, nicotine affects multiple brain structures and alters the release of many different neurotransmitters. These same brain areas and neurotransmitters are also directly involved in many different psychological disorders.

Although the idea that mental illness causes smoking seems to make sense, some researchers now believe that the arrow of causation points in the opposite direction. In the past decade, many studies have suggested that smoking triggers the onset of symptoms in people who are probably already vulnerable to the development of a mental disorder, especially major depressive disorder. Consider just a few studies:

The lifetime prevalence of developing major depressive disorder is strongly linked to the number of cigarettes consumed (Flensborg-Madsen & others, 2011). People who smoke have nearly twice the risk of later developing major depressive disorder than nonsmokers.

Several studies focusing on adolescents found that cigarette smoking predicted the onset of depressive symptoms, rather than the other way around (Beal & others, 2013; Boden & others, 2010; Goodman & Capitman, 2000; Windle & Windle, 2001).

In studies of people with bipolar disorder, daily cigarette smokers had worse symptoms and lengthier hospitalizations than nonsmoking bipolar patients (Dodd & others, 2010; Saiyad & El-Mallakh, 2012).

A positive association was found between smoking and the severity of symptoms experienced by people with anxiety disorders (McCabe & others, 2004).

In a study of people with schizophrenia, 90 percent of the patients had started smoking before their illness began (Kelly & McCreadie, 1999). In addition, among adolescent boys, smokers were almost twice as likely to later develop schizophrenia as nonsmokers (Weiser & others, 2004). These studies suggest that smoking may precipitate an initial schizophrenic episode in vulnerable people.

Further research may help disentangle the complex interaction between smoking and mental disorders, but one fact is known: Mentally ill cigarette smokers, like other smokers, are at much greater risk of premature disability and death. So, along with the psychological and personal suffering that accompanies almost all psychological disorders, those with mental illness carry the additional burden of consuming nearly half of all the cigarettes smoked in the United States.

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

Is the evidence sufficient to conclude that there is a causal relationship between cigarette smoking and the onset of mental illness symptoms? Why or why not?

Should tobacco companies be required to contribute part of their profits to the cost of mental health treatment and research?