14.4 Eating Disorders

ANOREXIA, BULIMIA, AND BINGE-EATING DISORDER

KEY THEME

Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder are psychological disorders characterized by severely disturbed, maladaptive eating behaviors.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the symptoms, characteristics, and causes of anorexia nervosa?

What are the symptoms, characteristics, and causes of bulimia nervosa?

What are the symptoms, characteristics, and causes of binge-eating disorder?

Eating disorders involve serious and maladaptive disturbances in eating behavior. The DSM-5 category in which eating disorders are included is technically called “Eating and Feeding Disorders,” which includes disorders of infancy and childhood. But here we will focus on disorders that tend to begin in adolescence or early adulthood. Eating disorders can include extreme reduction of food intake, severe bouts of overeating, and obsessive concerns about body shape or weight (DSM-5, 2013). The three main types of eating disorders are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder, which usually begin during adolescence or early adulthood (see TABLE 14.6). Ninety to 95 percent of the people who experience an eating disorder are female (Støving & others, 2011). Despite the 10-to-1 gender-difference ratio, the central features of eating disorders are similar for males and females.

eating disorder

A category of mental disorders characterized by severe disturbances in eating behavior.

Eating Disorders

| Anorexia Nervosa |

|---|

| • Severe and extreme disturbance in eating habits and calorie intake • Body weight that is significantly less than what would be considered normal for the person’s age, height, and gender, and refusal to maintain a normal body weight • Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat • Distorted perceptions about the severity of weight loss and a distorted self-image, such that even an extremely emaciated person may perceive herself as fat |

| Bulimia Nervosa |

| • Recurring episodes of binge eating, which is defined as an excessive amount of calories within a two-hour period • The inability to control or stop the excessive eating behavior • Recurrent episodes of purging, which is defined as using laxatives, diuretics, self-induced vomiting, or other methods to prevent weight gain |

| Binge-Eating Disorder |

| • Recurring episodes of binge eating • The inability to control or stop the excessive eating behavior • Not associated with recurrent episodes of purging or other methods to prevent weight gain |

!launch!

ANOREXIA NERVOSALIFE-THREATENING WEIGHT LOSS

Three key features define anorexia nervosa. First, the person refuses to maintain a minimally normal body weight. With a body weight that is significantly below normal, body mass index can drop to 12 or lower. Second, despite being dangerously underweight, the person with anorexia is intensely afraid of gaining weight or becoming fat. Third, she has a distorted perception about the size of her body. Although emaciated, she looks in the mirror and sees herself as fat or obese, denying the seriousness of her weight loss (DSM-5, 2013).

anorexia nervosa

An eating disorder characterized by excessive weight loss, an irrational fear of gaining weight, and distorted body self-perception.

The severe malnutrition caused by anorexia disrupts body chemistry in ways that are very similar to those caused by starvation. Basal metabolic rate decreases, as do blood levels of glucose, insulin, and leptin. Other hormonal levels drop, including the level of reproductive hormones. In women, reduced estrogen may result in the menstrual cycle stopping. In males, decreased testosterone disrupts sex drive and sexual function (Pinheiro & others, 2010). Because the ability to retain body heat is greatly diminished, people with severe anorexia often develop a soft, fine body hair called lanugo.

BULIMIA NERVOSA AND BINGE-EATING DISORDER

Like people with anorexia, people with bulimia nervosa fear gaining weight. Intense preoccupation and dissatisfaction with their bodies are also apparent. However, people with bulimia stay within a normal weight range or may even be slightly overweight. Another difference is that people with bulimia usually recognize that they have an eating disorder.

bulimia nervosa

An eating disorder characterized by binges of extreme overeating followed by self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, or other inappropriate methods to purge the excessive food and prevent weight gain.

People with bulimia nervosa experience extreme periods of binge eating, consuming as many as 50,000 calories on a single binge. Binges typically occur twice a week and are often triggered by negative feelings or hunger. During the binge, the person usually consumes sweet, high-calorie foods that can be swallowed quickly, such as ice cream, cake, and candy. Binges typically occur in secrecy, leaving the person feeling ashamed, guilty, and disgusted by his own behavior. After bingeing, he compensates by purging himself of the excessive food by self-induced vomiting or by misuse of laxatives or enemas. Once he purges, he often feels psychologically relieved. Some people with bulimia don’t purge themselves of the excess food. Rather, they use fasting and excessive exercise to keep their body weight within the normal range (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; DSM-5, 2013).

Like anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa can take a serious physical toll on the body. Repeated purging disrupts the body’s electrolyte balance, leading to muscle cramps, irregular heartbeat, and other cardiac problems, some potentially fatal. Stomach acids from self-induced vomiting erode tooth enamel, causing tooth decay and gum disease. Especially when practiced for long periods of time, frequent vomiting severely damages the gastrointestinal tract as well as the teeth (Powers, 2009).

Like people with bulimia, people with binge-eating disorder engage in bingeing behaviors (DSM-5, 2013). Unlike people with bulimia, they do not engage in purging or other behaviors that rid their bodies of the excess food. People with binge-eating disorder experience the same feelings of distress, lack of control, and shame that people with bulimia experience.

binge-eating disorder

An eating disorder characterized by binges of extreme overeating without use of self-induced vomiting or other inappropriate measures to purge the excessive food.

CAUSES OF EATING DISORDERSA COMPLEX PICTURE

Anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder involve decreases in brain activity of the neurotransmitter serotonin (Bailer & Kaye, 2011; Kuikka & others, 2001). Disrupted brain chemistry may also contribute to the fact that eating disorders frequently co-occur with other psychiatric disorders, such as major depressive disorder, substance abuse disorder, personality disorders, obsessive–

Family interaction patterns may also contribute to eating disorders. For example, critical comments by parents or siblings about a child’s weight, or parental modeling of disordered eating, may increase the odds that an individual develops an eating disorder (Quiles Marcos & others, 2013; Thompson & others, 2007). There also is evidence that some personality characteristics may be risk factors. For example, researchers have found that a tendency toward perfectionism in childhood—traits like needing to complete schoolwork perfectly and feeling a need to obey rules without question—was associated with later diagnosis of anorexia (Halmi & others, 2012).

Although cases of eating disorders have been documented for at least 150 years, contemporary Western cultural attitudes toward thinness and dieting probably contribute to the increased incidence of eating disorders today. This seems to be especially true with anorexia, which occurs predominantly in Western or “westernized” countries (Anderson-Fye, 2009; Cafri & others, 2005). We discuss this issue and the more general topic of culture’s effects on psychological disorders in the Culture and Human Behavior box “Culture-Bound Syndromes.”

CULTURE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

Culture-Bound Syndromes

At several points in this chapter, we’ve noted ways in which culture shapes the symptoms of psychological disorders. Psychological disorders do not always look the same in every culture. And further, some disorders, called culture-specific disorders or culture-bound syndromes, appear to be found only in a single culture.

For example, hikkomori is a syndrome first identified in Japan in the 1970s in adolescents and young adults (Kato & others, 2011; Teo, 2010). Hikkomori involves a pattern of extreme social withdrawal. People suffering from hikkomori become virtual recluses, often confining themselves to a single room in their parents’ home, sometimes for years. They refuse all social interaction or engagement with the outside world and, in some cases, do not speak even to family members who care for them. Locked away from the world, they spend their time alone in their room, preoccupied with watching television, playing video games, or surfing the Internet.

Most hikkomori are young males, but the syndrome has also been identified in women and middle-aged adults (Kato & others, 2012). Once rare, hikkomori has become a social phenomenon. Some estimates are that a million or more young Japanese live as hikkomori (Watts, 2002).

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that the types of psychological disorders are pretty much the same in every culture?

Hikkomori has symptoms in common with several Western disorders, including social anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and agoraphobia. However, its specific features are uniquely Japanese, reflecting social pressures and values. Some researchers believe that hikkomori is an extreme reaction to the pressure to succeed in school and to conform to social expectations that characterizes Japanese culture (Teo, 2010; Teo & Gaw, 2010). Also implicated is the close, almost symbiotic relationship that is encouraged between mothers and children, especially sons, in Japan. Japanese parents, apparently, are more tolerant of the hikkimori’s continuing dependency into adulthood than parents in other cultures might be (Wong & Ying, 2006).

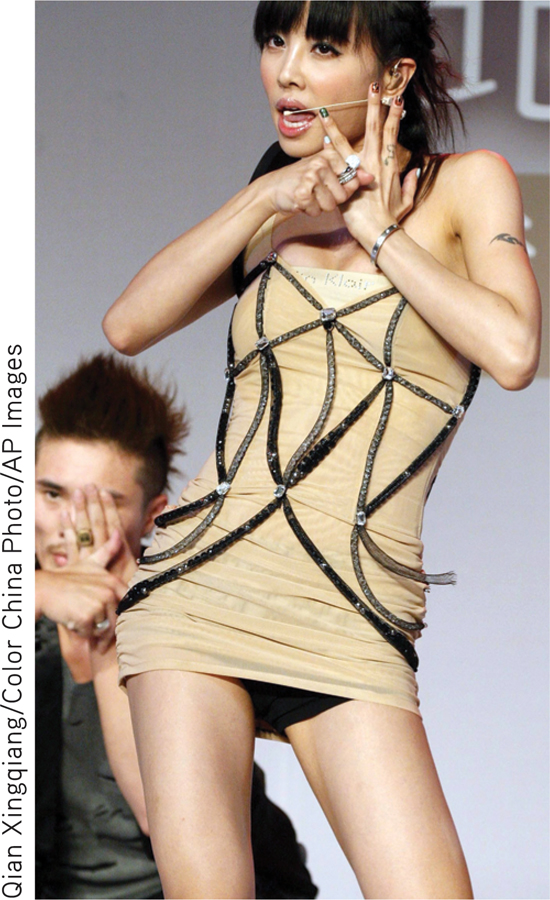

Western cultures have culture-bound syndromes, too. Consider the case of anorexia nervosa, discussed on pages 590–

The most common form of anorexia nervosa today has a distinctly different look. Its incidence is highest in the United States, Western Europe, and other “westernized” cultures, where an unnaturally slender physique is the cultural ideal (Anderson-Fye, 2009). In these cultures, self-starvation is associated with an intense fear of becoming fat (DSM-5, 2013). There is also a much higher incidence in women than in men, reflecting cultural beliefs about the importance of thinness for women (Keel & Klump, 2003).

Interestingly, researchers are seeing that the global transmission of social trends and information about psychological disorders appear to be contributing to the spread of syndromes that were once limited to a particular culture. For example, Chinese psychiatrist Sing Lee only learned about eating disorders during his training in the United Kingdom in the 1980s. Upon his return home to Hong Kong, he combed through hospital records and interviewed colleagues but could find very few occurrences of anorexia nervosa or other eating disorders in his native country. And, these few cases looked remarkably different from what he had observed in the U.K. In Hong Kong, young women with anorexia did not express a fear of being fat. Instead they attributed their extreme thinness to physical problems such as a bloated stomach or a poor appetite (Lee & others, 1993). Also, unlike patients in the West, Hong Kong patients tended to be from less privileged backgrounds and were less likely to follow fashion and beauty trends.

But that all changed in 1994, when fourteen-year-old schoolgirl Charlene Hsu Chi-Ying, emaciated and weighing only 75 pounds, collapsed and died on a busy street in the heart of Hong Kong (Watters, 2010). The dramatic nature of her death led to breathless media coverage. “Girl Who Died in Street Was a Walking Skeleton” read one headline. Within hours, many people in Hong Kong read about anorexia nervosa for the first time. With no traditional framework for understanding why an honor student would deliberately starve herself to death, the Hong Kong media sought out Western explanations, blaming images of women in the media and the fashion industry. Soon, celebrities were announcing their own battles with anorexia, and reports of anorexia became increasingly common. Over the next decade, eating disorders in Hong Kong, Japan, and other Asian countries had skyrocketed, and patients were much more likely to report a fear of being fat (S. Lee & others, 2010; Pike & Borovoy, 2004).

Many questions about culture-bound syndromes remain unanswered. For example, it is not clear whether culture-bound syndromes like hikkomori are distinct disorders, or whether they represent a culturally influenced expression of some more universal underlying pathology. And when a disorder like anorexia nervosa appears to spread across cultures, is the increased incidence actually caused by media coverage? Or does it simply reflect an increase in the diagnosis of cases that already existed? These questions are complex and unlikely to have a simple answer. As we’ve seen throughout this chapter, psychological disorders reflect the complex interaction of biological predispositions and psychological factors, and are always expressed within a particular social and cultural context. So, it’s unlikely that any single factor is responsible for the rate or symptoms of a particular psychological disorder.

CONCEPT REVIEW 14.2

Depressive Disorders, Bipolar Disorders, and Eating Disorders

Fill in the blank. Choose from: bulimia nervosa; anorexia nervosa; seasonal affective disorder (SAD); persistent depressive disorder; bipolar disorder; major depressive disorder; cyclothymic disorder.

Question 14.7

| 1. | Since moving to Fairbanks, Alaska, five years ago, Jon has experienced episodes of depression during the fall and winter months. Jon may be experiencing . |

Question 14.8

| 2. | Whenever she is under stress, Chelsea stops at a local grocery store and fills up her cart with ice cream, boxes of cookies, bags of chips, bakery goods, and bottles of soda. She will lock herself in her room and eat until she throws up. This occurs at least a couple of times a week. Chelsea is showing symptoms of . |

Question 14.9

| 3. | Sean has always had a negative, pessimistic attitude. Even positive events don’t shake his gloomy mood. Although Sean has a good job, he has few friends because they get tired of his constant complaints and negativity. Sean probably suffers from . |

Question 14.10

| 4. | Adam has suddenly become euphoric and energetic, sleeping only a few hours a night. He talks constantly about his far-fetched plans for making huge amounts of money. Adam most likely has . |

Question 14.11

| 5. | Mena, a 19-year-old college student, has missed almost all her classes during the last month. She sleeps 14 hours a day, has withdrawn from friends and family, feels worthless, and cries for no apparent reason. Mena is most likely suffering from . |

Question 14.12

| 6. | Emily runs twice a day, sometimes to the point of exhaustion. Because Emily believes that she is grossly overweight, she sometimes restricts her diet to green salads and grapefruit juice, even though her body weight is well below what is considered normal for her height. Emily is displaying the symptoms of . |

Question 14.13

| 7. | Ramesh has always been very unpredictable. One week he is lethargic and avoids all social contact, the next week he is very energetic, friendly, and outgoing. Even though his mood swings occur regularly, they are not severe enough to qualify as bipolar disorder. Ramesh’s moodiness may well be a symptom of . |

Test your understanding of Mood Disorders and Eating Disorders with

.

.