14.7 Schizophrenia

A DIFFERENT REALITY

KEY THEME

One of the most serious psychological disorders is schizophrenia, which involves severely distorted beliefs, perceptions, and thought processes.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the major symptoms of schizophrenia, and how do positive and negative symptoms differ?

What are the main subtypes of schizophrenia?

What factors have been implicated in the development of schizophrenia?

Normally, you’ve got a pretty good grip on reality. You can easily distinguish between external reality and the different kinds of mental states that you routinely experience, such as dreams or daydreams. But as we negotiate life’s many twists and turns, the ability to stay firmly anchored in reality is not a given. Rather, we’re engaged in an ongoing process of verifying the accuracy of our thoughts, beliefs, and perceptions.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that people with schizophrenia have a split personality?

If any mental disorder demonstrates the potential for losing touch with reality, it’s the one that Elyn Saks suffered from, schizophrenia. In media accounts and casual conversation, a person with schizophrenia is often mistakenly described as having “a split personality.” Elyn Saks explains the distinction: “the schizophrenic mind is not split, but shattered” (Saks, 2008). Schizophrenia is a psychological disorder that involves severely distorted beliefs, perceptions, and thought processes. During a schizophrenic episode, people lose their grip on reality, like Elyn screaming “I’m flying!” in the chapter Prologue. They become engulfed in an entirely different inner world, one that is often characterized by mental chaos, disorientation, and frustration.

schizophrenia

A psychological disorder in which the ability to function is impaired by severely distorted beliefs, perceptions, and thought processes.

Symptoms of Schizophrenia

The characteristic symptoms of schizophrenia can be described in terms of two broad categories: positive and negative symptoms. Positive symptoms reflect an excess or distortion of normal functioning. Positive symptoms include (1) delusions, or false beliefs; (2) hallucinations, or false perceptions; (3) severely disorganized thought processes and speech; and (4) severely disorganized behavior. In contrast, negative symptoms reflect an absence or reduction of normal functions, such as greatly reduced motivation, emotional expressiveness, or speech.

positive symptoms

In schizophrenia, symptoms that reflect excesses or distortions of normal functioning, including delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized thoughts and behavior.

negative symptoms

In schizophrenia, symptoms that reflect defects or deficits in normal functioning, including flat affect, alogia, and avolition.

According to DSM-5, schizophrenia is diagnosed when two or more of these characteristic symptoms are actively present for a month or longer. At least one symptom must be delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech. Usually, schizophrenia also involves a longer personal history, typically six months or more, of odd behaviors, beliefs, perceptual experiences, and other less severe signs of mental disturbance (Keshavan & others, 2011). In Elyn’s case, her symptoms lasted for years (Saks, 2008).

Schizophrenia may be diagnosed either with or without catatonia (DSM-5, 2013). Catatonia includes symptoms that reflect highly disturbed movements or actions. These may include bizarre postures or grimaces, complete immobility, no speech or very little speech, extremely agitated behavior, the echoing of words just spoken by another person, or imitation of the movements of others. People with catatonia will resist direction from others and may also assume rigid postures to resist being moved.

POSITIVE SYMPTOMSDELUSIONS, HALLUCINATIONS, AND DISTURBANCES IN SENSATION, THINKING, AND SPEECH

A delusion is a false belief that persists despite compelling contradictory evidence. Schizophrenic delusions are not simply unconventional or inaccurate beliefs. Rather, they are bizarre and far-fetched notions. The person may believe that secret agents are poisoning his food or that the next-door neighbors are actually aliens from outer space who are trying to transform him into a remote-controlled robot. At times, Elyn believed that she was an evil person who was capable of committing terrible violent acts, including killing children (Saks, 2008). The delusional person often becomes preoccupied with his erroneous beliefs and ignores any evidence that contradicts them.

delusion

A falsely held belief that persists despite compelling contradictory evidence.

Certain themes consistently appear in schizophrenic delusions. Delusions of reference reflect the person’s false conviction that other people’s behavior and ordinary events are somehow personally related to her. For example, she is certain that billboards and advertisements are about her or contain cryptic messages directed at her. In contrast, delusions of grandeur involve the belief that the person is extremely powerful, important, or wealthy. In delusions of persecution, the basic theme is that others are plotting against or trying to harm the person or someone close to her. Delusions of being controlled involve the belief that outside forces—aliens, the government, or random people, for example—are trying to exert control on the individual.

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

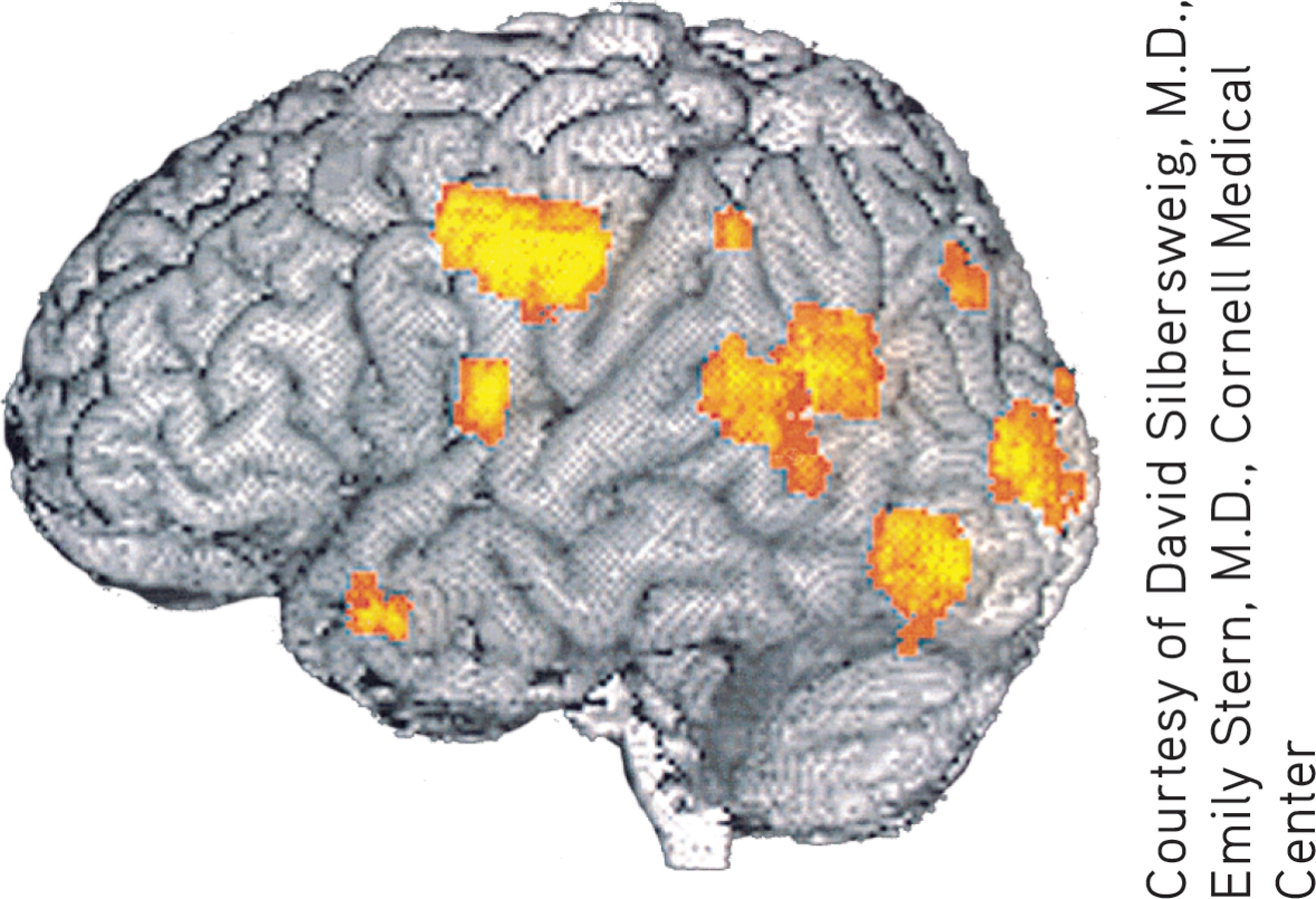

The Hallucinating Brain

Researcher David Silbersweig and his colleagues (1995) used PET scans to take a “snapshot” of brain activity during schizophrenic hallucinations. The scan shown here was recorded at the exact instant a schizophrenic patient hallucinated disembodied heads yelling orders at him. The bright orange areas reveal activity in the left auditory and visual areas of his brain, but not in the frontal lobe, which normally is involved in organized thought processes.

Schizophrenic delusions are often so convincing that they can provoke inappropriate or bizarre behavior. Delusional thinking may lead to dangerous behaviors, as when a person responds to his delusional ideas by hurting himself or attacking others.

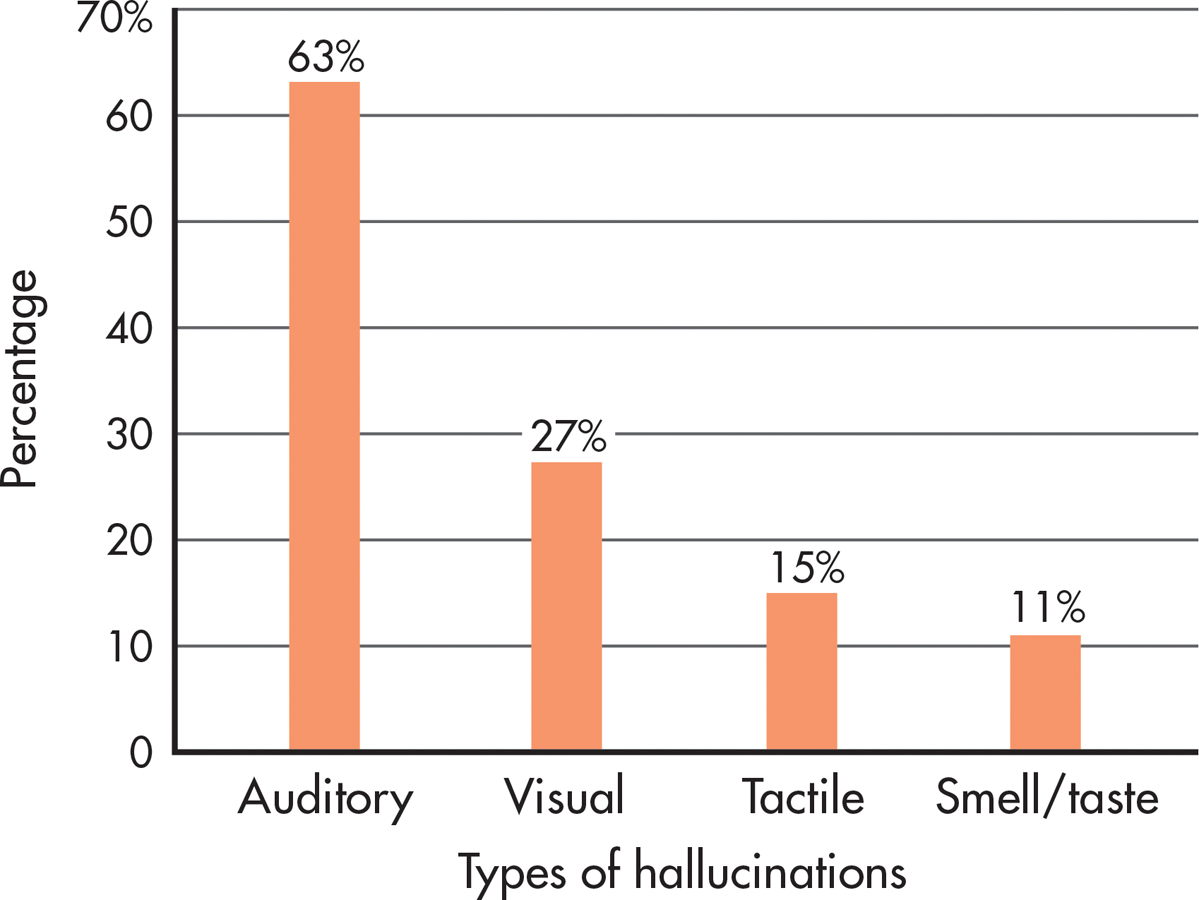

Among the most disturbing experiences in schizophrenia are hallucinations, which are false or distorted perceptions—usually voices or visual stimuli—that seem vividly real (see FIGURE 14.4). The content of hallucinations is often tied to the person’s delusional beliefs. For example, if she harbors delusions of grandeur, hallucinated voices may reinforce her grandiose ideas by communicating instructions from God, the devil, or angels. If the person harbors delusions of persecution, hallucinated voices or images may be extremely frightening, threatening, or accusing. The content of hallucinations and delusions may also be influenced by culture and religious beliefs.

hallucination

A false or distorted perception that seems vividly real to the person experiencing it.

People with schizophrenia might hear the roars of Satan or the whispers of children. They might move armies with their thoughts and receive instructions from other worlds. They might feel penetrated by scheming parasites, stalked by enemies, or praised by guardian angels. People with schizophrenia might also speak nonsensically, their language at once intricate and impenetrable. And many would push, or be pushed, to the edge of the social landscape, overcome by solitude.

—R. Walter Heinrichs (2005)

When a schizophrenic episode is severe, hallucinations can be virtually impossible to distinguish from objective reality. For example, Elyn reported that she could sometimes hear people whispering. At other times, she heard someone calling her name when she knew she was completely alone (Saks, 2008). When schizophrenic symptoms are less severe, the person may recognize that the hallucination is a product of his own mind. As Elyn reported, she knew that she had to try to control her psychotic thoughts at school and in social settings and was sometimes able to do so.

Other positive symptoms of schizophrenia include disturbances in sensation, thinking, and speech. Visual, auditory, and tactile experiences may seem distorted or unreal. For example, one woman described the sensory distortions in this way:

Looking around the room, I found that things had lost their emotional meaning. They were larger than life, tense, and suspenseful. They were flat, and colored as if in artificial light. I felt my body to be first giant, then minuscule. My arms seemed to be several inches longer than before and did not feel as though they belonged to me. (Anonymous, 1990)

Along with sensory distortions, the person may experience severely disorganized thinking. It becomes enormously difficult to concentrate, remember, and integrate important information while ignoring irrelevant information (Barch, 2005). The person’s mind drifts from topic to topic in an unpredictable, illogical manner, such as the Prologue example of Elyn’s ramblings to her classmates. Such disorganized thinking is often reflected in the person’s speech (Badcock & others, 2011). Ideas, words, and images are sometimes strung together in ways that seem nonsensical to the listener.

NEGATIVE SYMPTOMSFLAT AFFECT, ALOGIA, AND AVOLITION

Negative symptoms consist of marked deficits or decreases in behavioral or emotional functioning. One commonly seen negative symptom is referred to as diminished emotional expression or flat affect. Regardless of the situation, the person responds in an emotionally “flat” way, showing a dramatic reduction in emotional responsiveness and facial expressions. Speech is slow and monotonous, lacking normal vocal inflections. A closely related negative symptom is alogia, or greatly reduced production of speech. In alogia, verbal responses are limited to brief, empty comments.

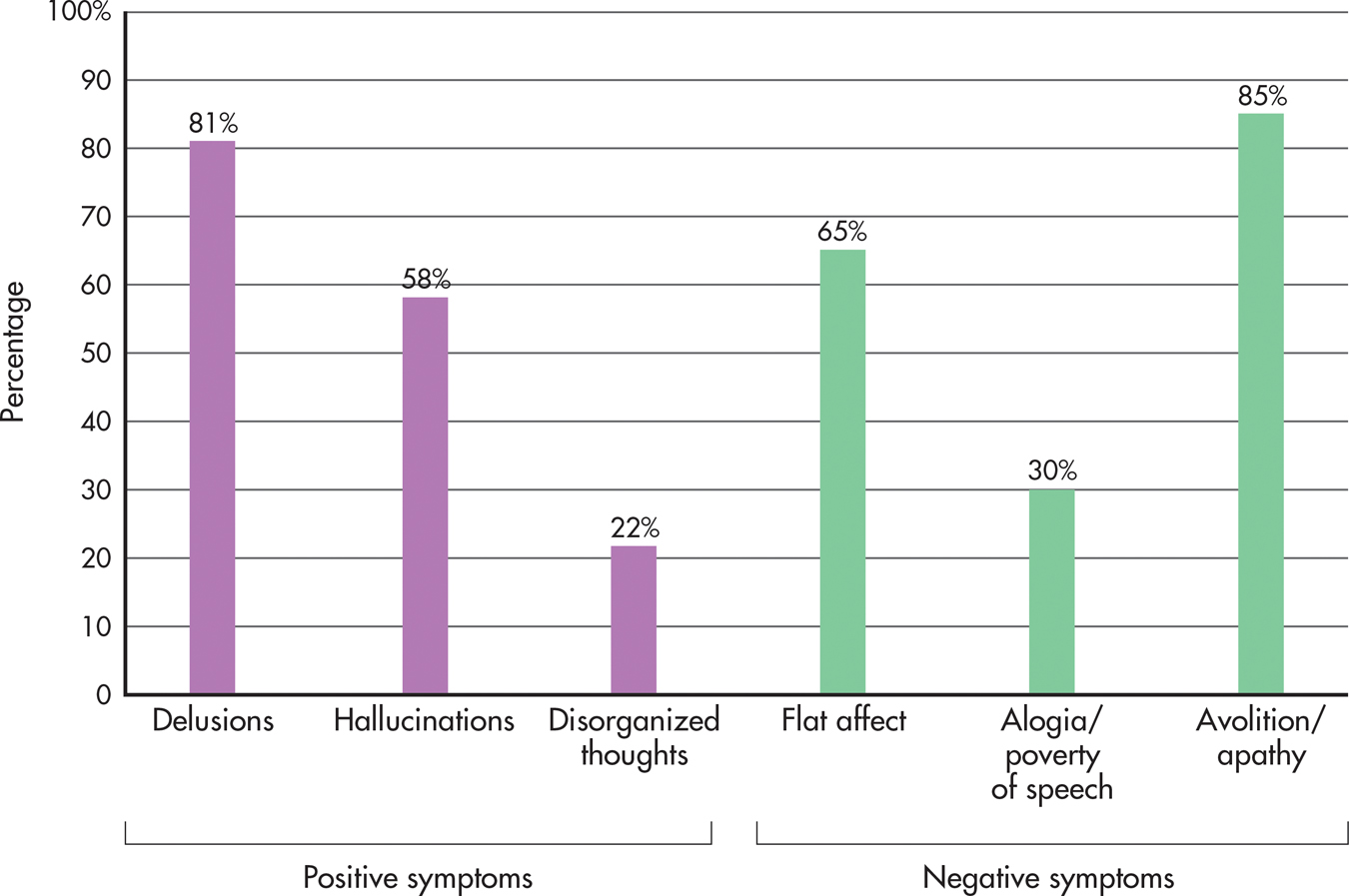

Finally, avolition refers to the inability to initiate or persist in even simple forms of goal-directed behaviors, such as dressing, bathing, or engaging in social activities. Instead, the person seems to be completely apathetic, sometimes sitting still for hours at a time. In combination, the negative symptoms accentuate the isolation of the person with schizophrenia, who may appear uncommunicative and completely disconnected from his or her environment. Not everyone with schizophrenia experiences negative symptoms. Elyn Saks wrote of feeling lucky to have escaped experiencing most negative symptoms (Saks, 2008). FIGURE 14.5 shows the frequency of positive and negative symptoms at the time of hospitalization for schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia Symptoms and Culture

Symptoms of schizophrenia often vary across cultures. For example, there can be cultural variations in delusional themes and the content of hallucinations (Bauer & others, 2011).

Delusions are a prime example of a symptom often rooted in culture. Indeed, some themes that would be considered to be delusional in one culture might be widely held beliefs in another culture. The International Study on Psychotic Symptoms examined data from over 1,000 people with schizophrenia in seven countries: Austria, Georgia, Ghana, Lithuania, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Poland (Stompe & others, 2006). Among the delusions experienced by the people in this sample, 16.8 percent of the content was culturally specific. For example, in Nigeria and Ghana there were relatively high rates of delusions that involved “being an angel or a prophet,” concepts that are integral parts of these cultures.

Even within a single culture, the content of delusions changes as the culture shifts. A study of delusions in U.S. inpatient psychiatric patients found that delusions have changed over time. During World War II, delusions tended to center on Nazi soldiers. Recently, delusions are more likely to involve technology (Cannon & Kramer, 2012). Joel Gold and Ian Gold (2012) describe a common type of delusion involving technology—people who believe that they are being filmed continuously, with the footage being aired as if they were secretly cast on a television show like Big Brother. The Golds refer to this as the “Truman Show” delusion after the 1998 film in which a whole town is secretly filmed for years as global entertainment.

The Prevalence and Course of Schizophrenia

Every year, about 200,000 new cases of schizophrenia are diagnosed in the United States, and annually, approximately 1 million Americans are treated for schizophrenia. All told, about 1 percent of the U.S. population will experience at least one episode of schizophrenia at some point in life (Rado & Janicak, 2009). Worldwide, no society or culture is immune to this mental disorder. Researchers have long believed that most cultures correspond very closely to the 1 percent rate of schizophrenia seen in the United States (Minzenberg & others, 2011). However, a comprehensive review of almost 200 studies concluded that global rates of schizophrenia were closer to 4 percent, meaning that schizophrenia may be far more widespread than once believed (Saha & others, 2005).

The onset of schizophrenia typically occurs during young adulthood, as it did with Elyn (Gogtay & others, 2011). However, the course of schizophrenia is marked by enormous individual variability. Even so, a few global generalizations are possible (Malla & Payne, 2005; Walker & others, 2004). The good news is that about one-quarter of those who experience an episode of schizophrenia recover completely and never experience another episode. Another one-quarter experience recurrent episodes of schizophrenia but often with only minimal impairment in the ability to function.

Now the bad news. For the rest of those who have experienced an episode of schizophrenia—about one-half of the total—schizophrenia becomes a chronic mental illness, and the ability to function may be severely impaired. The people in this last category face the prospect of repeated hospitalizations and extended treatment. Thus, chronic schizophrenia places a heavy emotional, financial, and psychological burden on people with the disorder, their families, and society (Combs & Mueser, 2007). Yet, as Elyn’s story shows, a diagnosis of schizophrenia does not mean that a person cannot be successful in his or her career and personal life.

Cultural factors also seem to affect the outcome of schizophrenia. Despite less access to mental health care, people with schizophrenia often have a better outcome in the developing world than in the developed world (Haro & others, 2011; World Health Organization, 1998). For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) found that full recovery after a single episode of psychosis occurred in just 3 percent of cases in the United States but in 54 percent of cases in India. WHO (1998) suggests that people in the developing world might be more accepting of mental illness, and are more likely to have extended family support systems than people in the developed world.

Recent studies have qualified these findings. For example, Josep Haro and others (2011) found that people with schizophrenia living in the developing world tended to experience a greater decline in their symptoms over time than those with schizophrenia living in the developed world. But they also fared worse in terms of life skills, such as holding a job and living independently. The decline in symptoms did not coincide with improved life functioning. Clearly, culture is an important factor in the experience and course of schizophrenia.

Explaining Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is an extremely complex disorder. There is enormous individual variability in the onset, symptoms, duration, and recovery from schizophrenia. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the causes of schizophrenia seem to be equally complex. In this section, we’ll survey some of the factors that have been implicated in the development of schizophrenia.

GENETIC FACTORSFAMILY, TWIN, ADOPTION, AND GENE STUDIES

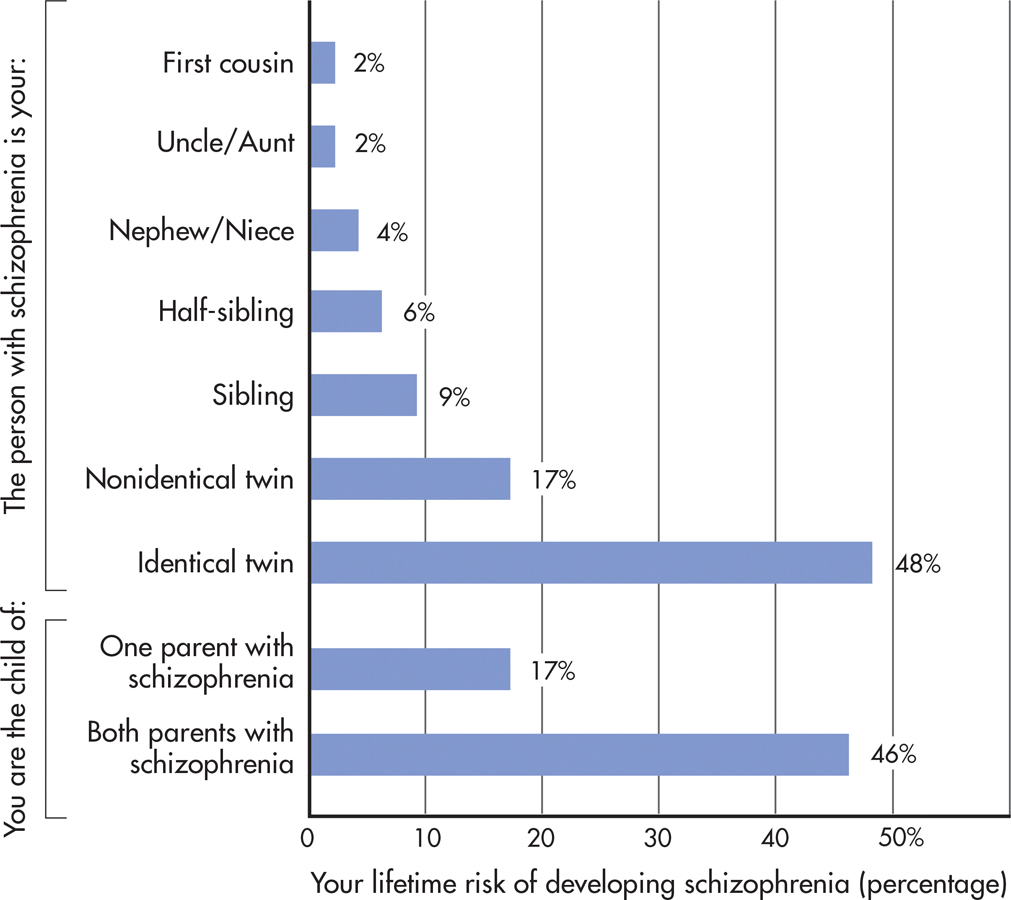

Studies of families, twins, and adopted individuals have firmly established that genetic factors play a significant role in many cases of schizophrenia (Pogue-Geile & Yokley, 2010). First, family studies have consistently shown that schizophrenia tends to cluster in certain families (Choi & others, 2007; Helenius & others, 2012). Second, family and twin studies have consistently shown that the more closely related a person is to someone who has schizophrenia, the greater the risk that she will be diagnosed with schizophrenia at some point in her lifetime (see FIGURE 14.6). Third, adoption studies have consistently shown that if either biological parent of an adopted individual had schizophrenia, the adopted individual is at greater risk to develop schizophrenia (Wynne & others, 2006). And fourth, by studying families that display a high rate of schizophrenia, researchers have consistently found that the presence of certain genetic variations seems to increase susceptibility to the disorder (Fanous & others, 2005; Williams & others, 2005).

Ironically, some of the best evidence that points to genetic involvement in schizophrenia—the almost 50 percent risk rate for a person whose identical twin has schizophrenia—is the same evidence that underscores the importance of environmental factors (Joseph & Leo, 2006; Oh & Petronis, 2008). If schizophrenia were purely a matter of inherited maladaptive genes, then you would expect a risk rate much closer to 100 percent for monozygotic twins. Obviously, nongenetic factors must play a role in explaining why half of identical twins with a schizophrenic twin do not develop schizophrenia.

Nevertheless, scientists are getting closer to identifying some of the specific genetic patterns that are associated with an increased risk of developing schizophrenia. New research using sophisticated gene analysis techniques confirms the incredibly complex role that genes play in the development of schizophrenia (Gilman & others, 2012; Rapoport & others, 2012). For example, a recent study of people with schizophrenia with no family history of the disease found that genetic mutations were much higher in the schizophrenic patients than in individuals without schizophrenia (Girard and others, 2011). These mutations were present in many different genes, including genes that had not previously been associated with schizophrenia.

In another large-scale research project, three different research teams compared DNA samples from thousands of people diagnosed with schizophrenia with DNA samples from control groups of people who did not have schizophrenia (Purcell & others, 2009; Shi & others, 2009; Stefansson & others, 2009). Some of the people in the control groups had other mental or physical disorders, but most were healthy. The researchers were looking for specific genetic variations that were more common in the genomes of people with schizophrenia than in people without schizophrenia.

Collectively, the studies found that schizophrenia was associated with literally thousands of common gene variations. Some of the specific variants were quite rare, while others were quite common. Taken individually, none of the gene variants is capable of “causing” schizophrenia. Even in combination, the genetic variants are only associated with an increased risk of developing schizophrenia.

As yet, no specific pattern of genetic variation can be identified as the genetic “cause” of schizophrenia. However, three particularly interesting findings stand out. First, some of the same unique genetic patterns associated with schizophrenia have also been found in DNA samples from people with bipolar disorder (Purcell & others, 2009). This finding suggests that bipolar disorder and schizophrenia might share some common genetic origins. Second, also implicated were several chromosome locations that are associated with genes that influence brain development, memory, and cognition. Finally, a large number of the gene variants were found to occur on a specific chromosome that is also known to harbor genes involved in the immune response (Shi & others, 2009). Later in this section, we’ll discuss some intriguing links between viral infections and schizophrenia, which suggests that the immune system may be implicated in the development of schizophrenia.

PATERNAL AGEOLDER FATHERS AND THE RISK OF SCHIZOPHRENIA

Despite the fact that family and twin studies point to the role of genetic factors in the risk of developing schizophrenia, no genetic model thus far explains all of the patterns of schizophrenia occurrence within families (Insel & Lehner, 2007). Adding to the complexity, schizophrenia often occurs in individuals with no family history of mental disorders. Elyn, for example, has an uncle who suffered from depression but no close relatives who suffered from schizophrenia or any other serious mental disorders (Saks, 2008).

One explanation for these anomalies is that for each generation, new cases of schizophrenia arise from genetic mutations carried in the sperm of the biological fathers, especially older fathers. As men age, their sperm cells continue to reproduce by dividing. By the time a male is 20, his sperm cells have undergone about 200 divisions; by the time he is 40, there have been about 660 divisions. As the number of divisions increases over time, the sperm cells accumulate genetic mutations that can then be passed on to that man’s offspring. Hence, the theory goes, as paternal age increases, the risk of offspring developing schizophrenia also increases (Bajwa & others, 2011).

Researcher Dolores Malaspina and her colleagues (2001) explored this notion by reviewing data on more than 87,000 people born in Jerusalem from 1964 to 1976. Of this group, 658 people had been diagnosed with schizophrenia by 1998. After controlling for various risk factors, the researchers found that paternal age was a strong and significant predictor of the schizophrenia diagnoses. Specifically, Malaspina and her colleagues (2001) found that:

Men in the 45–

49 age group who fathered children were twice as likely to have offspring with schizophrenia as compared to fathers age 25 and under. Men in the 50-plus age range were three times more likely to produce offspring with schizophrenia.

More than one-quarter of the schizophrenia cases could be attributed to the father’s age.

The mother’s age appeared to play no role in the development of schizophrenia.

Clearly, then, paternal age is a potential risk factor. However, it’s important to keep in mind that three-quarters of the cases of schizophrenia in this study were not associated with older paternal age.

THE IMMUNE SYSTEMTHE VIRAL INFECTION THEORY

Another provocative theory is that schizophrenia might be caused by exposure to an influenza virus or other viral infection during prenatal development or shortly after birth. A virus might seem an unlikely cause of a serious mental disorder, but viruses can spread to the brain and spinal cord by traveling along nerves. According to this theory, exposure to a viral infection during prenatal development or early infancy affects the developing brain, producing changes that make the individual more vulnerable to schizophrenia later in life.

There is growing evidence to support the viral infection theory. In one compelling study, psychiatrist Alan S. Brown and his colleagues (2004) compared stored blood samples of 64 mothers of people who later developed schizophrenia with a matched set of blood samples from women whose children did not develop schizophrenia. Both sets of blood samples had been collected years earlier during the women’s pregnancies. After analyzing the blood samples for the presence of influenza antibodies, Brown and his colleagues (2004) found that women who had been exposed to the flu virus during the first trimester had a sevenfold increased risk of bearing a child who later developed schizophrenia.

Previous studies using maternal recall and the dates of influenza epidemics have demonstrated similar findings: Children whose mothers were exposed to a flu virus during pregnancy, especially during the first or second trimester, show an increased rate of schizophrenia (Carter, 2008; Yudofsky, 2009). A related finding is that schizophrenia occurs more often in people who were born in the winter and spring months, when upper respiratory infections are most common (Disanto & others, 2012; Torrey & others, 1996).

ABNORMAL BRAIN STRUCTURESLOSS OF GRAY MATTER

Researchers have found that about half of the people with schizophrenia show some type of brain structure abnormality. The most consistent finding has been the enlargement of the fluid-filled cavities, called ventricles, located deep within the brain (Kempton & others, 2010; Meduri & others, 2010). However, researchers are not certain how enlarged ventricles might be related to schizophrenia.

Other differences that have been found are a loss of gray matter tissue and lower overall volume of the brain (Olabi & others, 2011; Vita & others, 2012). As we discussed in Chapter 2, gray matter refers to the glial cells, neuron cell bodies, and unmyelinated axons that make up the quarter-inch-thick cerebral cortex. Researchers have found that the loss of gray matter is associated with increased clinical symptoms and decreased cognitive functioning among people with schizophrenia (Asami & others, 2012).

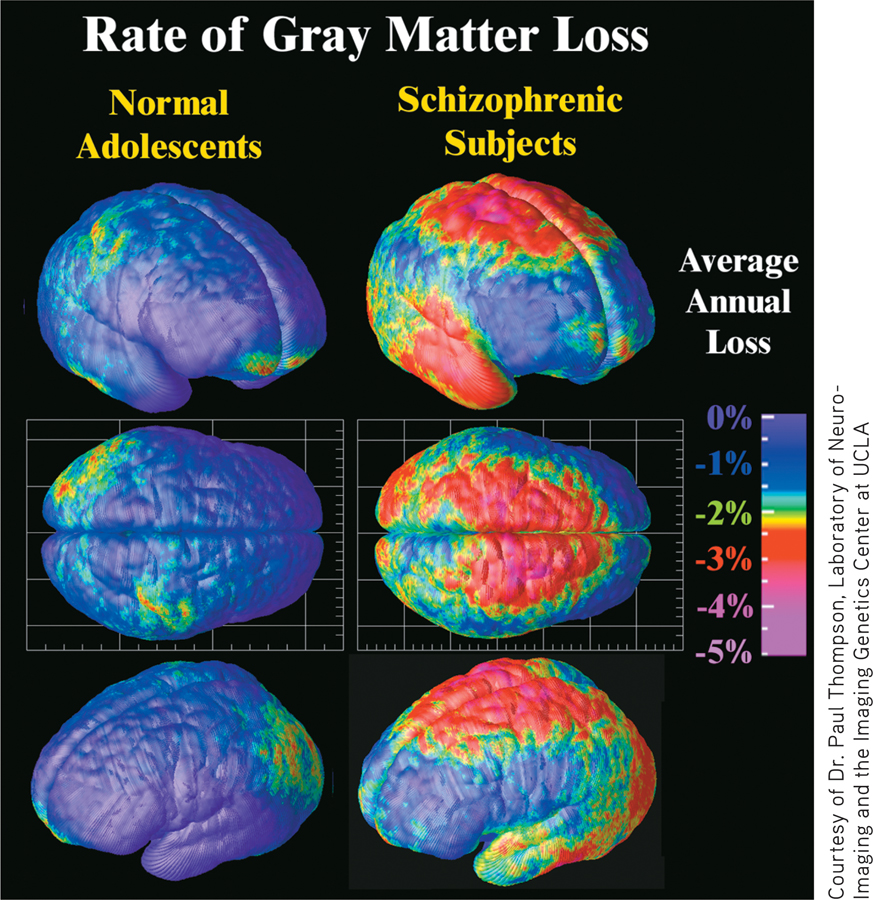

To investigate the neurological development of schizophrenia, neuroscientist Paul M. Thompson and his colleagues (2001) undertook a prospective study of brain structure changes in 12 adolescents with early-onset childhood schizophrenia. The six females and six males had all experienced schizophrenic symptoms, including psychotic symptoms, before the age of 12. The intent of the study was to provide a visual picture of the timing, rates, and anatomical distribution of brain structure changes in adolescents with schizophrenia.

Each of the 12 adolescents was scanned repeatedly with high-resolution MRIs over a five-year period, beginning when the teenagers were about 14. The adolescents were carefully matched with healthy teens of the same gender, age, socioeconomic background, and height. The findings of this important study are featured in the Focus on Neuroscience.

Although there is evidence that brain abnormalities are found in schizophrenia, such findings do not prove that brain abnormalities are the sole cause of schizophrenia. First, some people with schizophrenia do not show brain structure abnormalities. Second, the evidence is correlational. Researchers are still investigating whether differences in brain structures and activity are the cause or the consequence of schizophrenia. Third, the kinds of brain abnormalities seen in schizophrenia are also seen in other mental disorders. Rather than specifically causing schizophrenia, it’s quite possible that brain abnormalities might contribute to psychological disorders in general.

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

Schizophrenia: A Wildfire in the Brain

In a five-year prospective study, neuroscientist Paul Thompson and his colleagues (2001) used high-resolution brain scans to map brain structure changes in normal adolescents and adolescents with early-onset schizophrenia. Thompson found marked differences in the brain development of normal teens and teens with schizophrenia. As expected, the healthy teenagers showed a gradual, small loss of gray matter—about 1 percent—over the five-year study. This loss is due to the normal pruning of unused brain connections that takes place during adolescence (see Chapter 9).

But in sharp contrast to the normal teens, the teenagers with schizophrenia showed a severe loss of gray matter that developed in a specific, wavelike pattern. The loss began in the parietal lobes and, over the five years of the study, progressively spread forward to the temporal and frontal regions. As Thompson (2001) noted, “We were stunned to see a spreading wave of tissue loss that began in a small region of the brain. It moved across the brain like a forest fire, destroying more tissue as the disease progressed.” The brain images show the average rate of gray matter loss over the five-year period. Gray matter loss ranged from about 1 percent (blue) in the normal teens to more than 5 percent (pink) in the schizophrenic teens. One fascinating finding was that the amount of gray matter loss was directly correlated to the teenage patients’ clinical symptoms. Psychotic symptoms increased the most in the participants who lost the greatest quantity of gray matter.

Also, the pattern of loss mirrored the progression of neurological and cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia. For example, more rapid gray matter loss in the temporal lobes was associated with more severe positive symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions. More rapid loss of gray matter in the frontal lobes was strongly correlated with the severity of negative symptoms, including flat affect and poverty of speech. When the participants were 18 to 19 years old and the final brain scans were taken, the patterns of gray matter loss were similar to those found in the brains of adult patients with schizophrenia.

Despite the wealth of information generated by Thompson’s study, the critical question remains unanswered: What sparks the cerebral forest fire in the schizophrenic brain?

ABNORMAL BRAIN CHEMISTRYHYPOTHESES RELATED TO NEUROTRANSMITTERS

There are several hypotheses that attribute schizophrenia to imbalances in neurotransmitters. The oldest of these is the dopamine hypothesis, which attributes schizophrenia to excessive activity of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the brain. Two pieces of indirect evidence support this notion. First, antipsychotic drugs, such as Haldol, Thorazine, and Stelazine, reduce or block dopamine activity in the brain. These drugs reduce schizophrenic symptoms, especially positive symptoms, in many people. Second, drugs that enhance dopamine activity in the brain, such as amphetamines and cocaine, can produce schizophrenia-like symptoms in normal adults or increase symptoms in people who already have schizophrenia.

However, there is also evidence that contradicts the dopamine hypothesis (Jucaite & Nyberg, 2012). For example, not all individuals who have schizophrenia experience a reduction of symptoms in response to the antipsychotic drugs that reduce dopamine activity in the brain. And for many patients, these drugs reduce some but not all schizophrenic symptoms, and tend to reduce positive symptoms more than negative symptoms (Kendler & Schaffner, 2011). One new theory is that some parts of the brain, such as the limbic system, may have too much dopamine, while other parts of the brain, such as the cortex, may have too little (Combs & Mueser, 2007; Kendler & Schaffner, 2011). There also is increasing evidence that imbalances in other neurotransmitters—glutamate and adenosine—are related to schizophrenia (Boison & others, 2012; Lau & others, 2013; Moghaddam & Javitt, 2011). Thus, the connection between neurotransmitters and schizophrenia symptoms remains unclear.

PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORSUNHEALTHY FAMILIES

Researchers have investigated such factors as dysfunctional parenting, disturbed family communication styles, and critical or guilt-inducing parental styles as possible contributors to schizophrenia (Johnson & others, 2001). However, no single psychological factor seems to emerge consistently as causing schizophrenia. Rather, it seems that those who are genetically predisposed to develop schizophrenia may be more vulnerable to the effects of disturbed family environments (Tienari & Wahlberg, 2008).

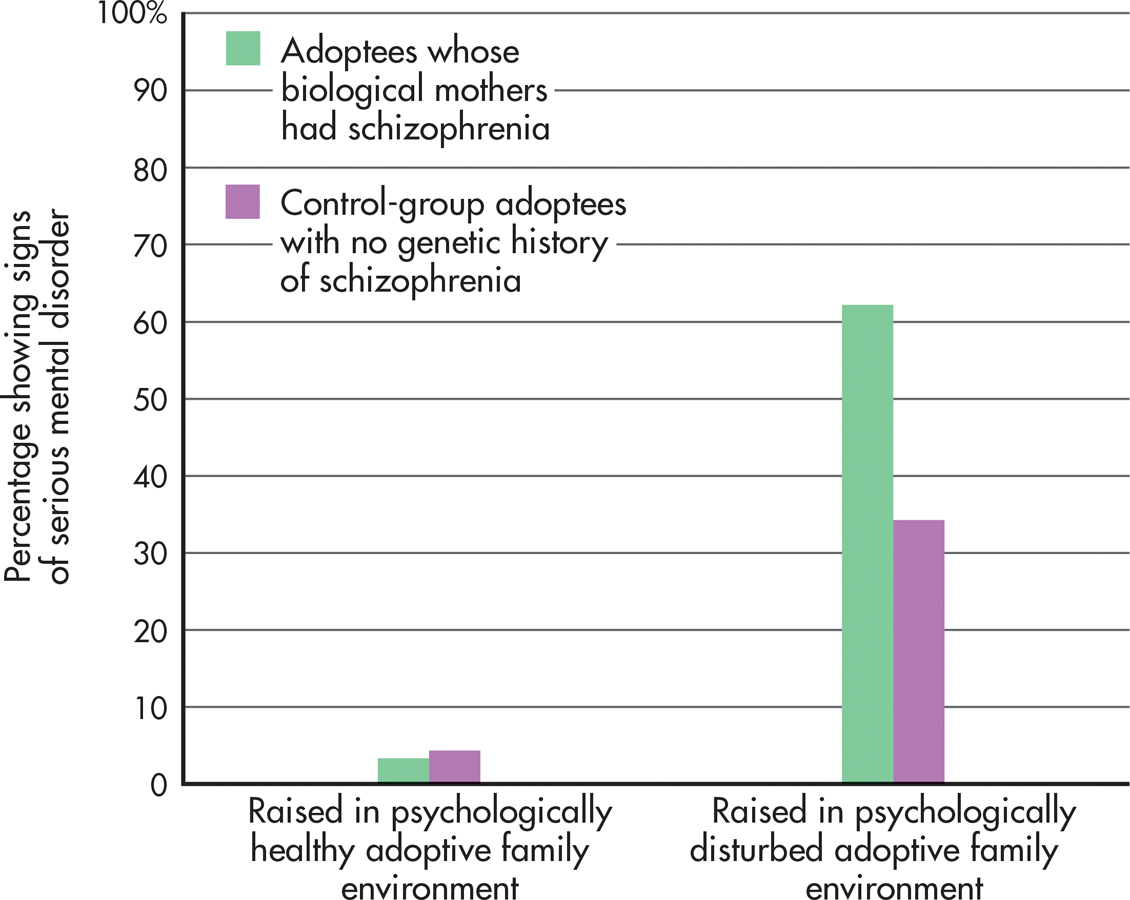

Strong support for this view comes from a landmark study conducted by Finnish psychiatrist Pekka Tienari and his colleagues (1987, 1994). In the Finnish Adoptive Family Study of Schizophrenia, researchers followed about 150 adopted individuals whose biological mothers had schizophrenia. As part of their study, the researchers assessed the adoptive family’s degree of psychological adjustment, including the mental health of the adoptive parents. The study also included a control group of about 180 adopted individuals whose biological mothers did not have schizophrenia.

Tienari and his colleagues (1994, 2006; Wynne & others, 2006) found that adopted children with a schizophrenic biological mother had a much higher rate of schizophrenia than did the children in the control group. However, this was true only when the children were raised in a psychologically disturbed adoptive home. As you can see in FIGURE 14.7, when children with a genetic background of schizophrenia were raised in a psychologically healthy adoptive family, they were no more likely than the control-group children to develop schizophrenia.

Although adopted children with no genetic history of schizophrenia were less vulnerable to the psychological stresses of a disturbed family environment, they were by no means completely immune to such influences. As FIGURE 14.7 shows, one-third of the control-group adoptees developed symptoms of a serious psychological disorder if they were raised in a disturbed family environment.

Tienari’s study underscores the complex interaction of genetic and environmental factors. Clearly, children who were genetically at risk to develop schizophrenia benefited from being raised in a healthy psychological environment. Put simply, a healthy psychological environment may counteract a person’s inherited vulnerability for schizophrenia. Conversely, a psychologically unhealthy family environment can act as a catalyst for the onset of schizophrenia, especially for those individuals with a genetic history of schizophrenia (Tienari & Wahlberg, 2008).

After more than a century of intensive research, schizophrenia remains a baffling disorder. Thus far, no single biological, psychological, or social factor has emerged as the causal agent in schizophrenia. And it’s virtually impossible to know what caused schizophrenia in any single individual like Elyn. Nevertheless, researchers are expressing greater confidence that the pieces of the schizophrenia puzzle are beginning to form a more coherent picture.

Even if the exact causes of schizophrenia remain elusive, there is still reason for optimism. In the past few years, new antipsychotic drugs, such as those that Elyn takes, have been developed that are much more effective in treating both the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia (Sharif & others, 2007). In the next chapter, we’ll take a detailed look at the different treatments and therapies for schizophrenia and other psychological disorders.

CONCEPT REVIEW 14.3

Personality Disorders, Dissociative Disorders, and Schizophrenia

Fill in the blank next to each example below with one of the following psychological disorders: dissociative amnesia with dissociative fugue, dissociative identity disorder, antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, schizophrenia.

Question 14.14

| 1. | Jay, a high school physics teacher in New York City, disappeared three days after his wife unexpectedly left him. Six months later, he was discovered tending bar in Miami Beach. Calling himself Martin, he claimed to have no recollection of his past life. |

Question 14.15

| 2. | Bob was fired from yet another job, this time for stealing and forging payroll checks. “They were so stupid at that place, they deserved to lose that money,” he bragged to his girlfriend. |

Question 14.16

| 3. | Norma has frequent memory gaps and cannot account for her whereabouts during certain periods of time. While being interviewed by a clinical psychologist, she began speaking in a childlike voice. She claimed that her name was Donna and that she was only 6 years old. Moments later, she seemed to revert to her adult voice and had no recollection of claiming that her name was Donna. |

Question 14.17

| 4. | Leslie seems charming and vivacious when you first meet her, but you soon discover that she is extremely moody, jealous, and possessive; terrified of being alone; and prone to self-destructive behavior. |

Question 14.18

| 5. | By the time the neighbors called the police, Dwight had barricaded all the doors and windows of his house because the voices had told him that aliens were coming to kidnap him. |

Test your understanding of Schizophrenia with

.

.

Closing Thoughts

In this chapter, we’ve looked at the symptoms and causes of several psychological disorders. We’ve seen that some of the symptoms of psychological disorders represent a sharp break from normal experience. The behavior of Elyn Saks in the Prologue is an example of the severely disrupted functioning characteristic of schizophrenia. In contrast, the symptoms of other psychological disorders, such as the anxiety disorders and depressive disorders, differ from normal experience primarily in their degree, intensity, and duration.

Psychologists are only beginning to understand the causes of many psychological disorders. The broad picture that emerges reflects a familiar theme: Biological, psychological, and social factors all contribute to the development of psychological disorders. In the next chapter, we’ll look at how psychological disorders are treated.

In the final section, Psych for Your Life, we’ll explore one of the most serious consequences of psychological problems—suicide. Because people who are contemplating suicide often turn to their friends before they seek help from a mental health professional, we’ll also suggest several ways in which you can help a friend who expresses suicidal intentions.