15.4 Behavior Therapy

KEY THEME

Behavior therapy uses learning principles to directly change problem behaviors.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the key assumptions of behavior therapy?

What therapeutic techniques are based on classical conditioning, and how are they used to treat psychological disorders and problems?

What therapy treatments are based on operant conditioning, and how are they used to treat psychological disorders and problems?

Psychoanalysis, client-centered therapy, and other insight-oriented therapies maintain that the road to psychologically healthier behavior is through increased self-understanding of motives and conflicts. As insights are acquired through therapy, problem behaviors and feelings presumably will give way to more adaptive behaviors and emotional reactions.

However, gaining insight into the source of problems does not necessarily result in desirable changes in behavior and emotions. Even though you fully understand why you are behaving in counterproductive ways, your maladaptive or self-defeating behaviors may continue. For instance, an adult who is extremely anxious about public speaking may understand that he feels that way because he was raised by a critical and demanding parent. But having this insight into the underlying cause of his anxiety may do little, if anything, to reduce his anxiety or change his avoidance of public speaking.

In sharp contrast to the insight-oriented therapies we discussed in the preceding sections, the goal of behavior therapy, also called behavior modification, is to modify specific problem behaviors, not to change the entire personality. And, rather than focusing on the past, behavior therapists focus on current behaviors.

behavior therapy

A type of psychotherapy that focuses on directly changing maladaptive behavior patterns by using basic learning principles and techniques; also called behavior modification.

Behavior therapists assume that maladaptive behaviors are learned, just as adaptive behaviors are. Thus, the basic strategy in behavior therapy involves unlearning maladaptive behaviors and learning more adaptive behaviors in their place. Behavior therapists employ techniques that are based on the learning principles of classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning to modify the problem behavior.

Techniques Based on Classical Conditioning

Just as Pavlov’s dogs learned to salivate to a ringing bell that had become associated with food, learned associations can be at the core of some maladaptive behaviors, including strong negative emotional reactions. In the 1920s, psychologist John Watson demonstrated this phenomenon with his famous “Little Albert” study. In Chapter 5, we described how Watson classically conditioned an infant known as Little Albert to fear a tame lab rat by repeatedly pairing the rat with a loud clanging sound. Over time, Albert’s conditioned fear generalized to other furry objects, including a fur coat, cotton, and a Santa Claus mask (Watson & Rayner, 1920).

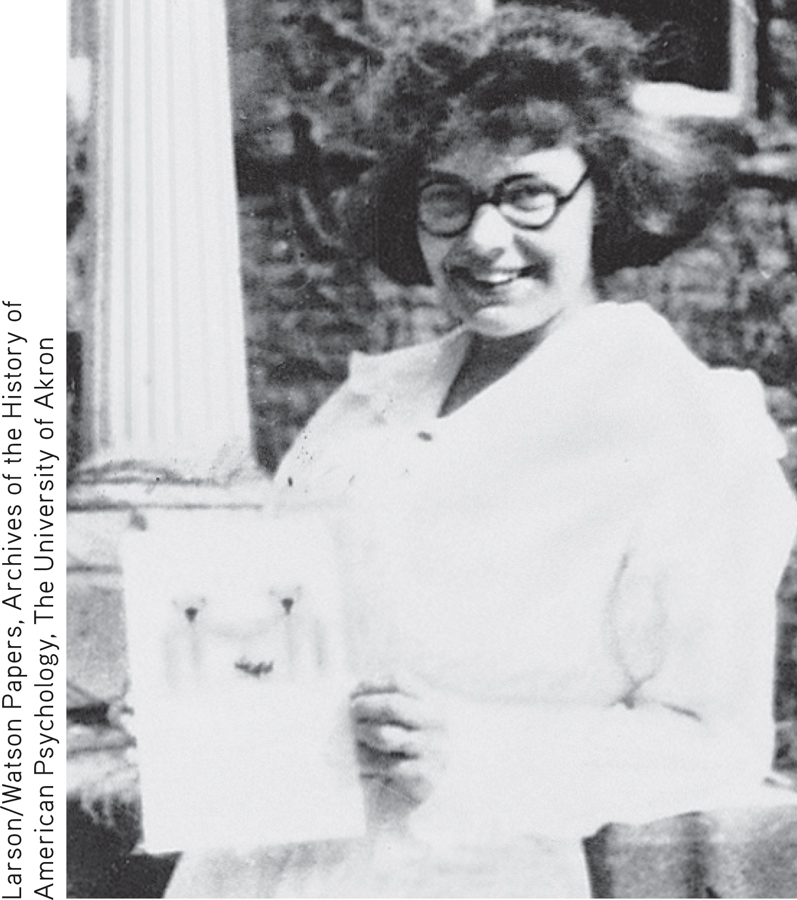

MARY COVER JONES: THE FIRST BEHAVIOR THERAPIST

Watson himself never tried to eliminate Little Albert’s fears. But Watson’s research inspired one of his students, Mary Cover Jones, to explore ways of reversing conditioned fears. With Watson acting as a consultant, Jones (1924a) treated a 3-year-old named Peter who “seemed almost to be Albert grown a bit older.” Like Little Albert, Peter was fearful of various furry objects, including a tame rat, a fur coat, cotton, and wool. Because Peter was especially afraid of a tame rabbit, Jones focused on eliminating the rabbit fear. She used a procedure that has come to be known as counterconditioning—the learning of a new conditioned response that is incompatible with a previously learned response.

counterconditioning

A behavior therapy technique based on classical conditioning that involves modifying behavior by conditioning a new response that is incompatible with a previously learned response.

Jones’s procedure was very simple (Jones, 1924b; Watson, 1924). The caged rabbit was brought into Peter’s view but kept far enough away to avoid eliciting fear (the original conditioned response). With the rabbit visible at a tolerable distance, Peter sat in a high chair and happily munched his favorite snack, milk and crackers. Peter’s favorite food was used because, presumably, the enjoyment of eating would naturally elicit a positive response (the desired conditioned response). Such a positive response would be incompatible with the negative response of fear.

Every day for almost two months, the rabbit was inched closer and closer to Peter as he ate his milk and crackers. As Peter’s tolerance for the rabbit’s presence gradually increased, he was eventually able to hold the rabbit in his lap, petting it with one hand while happily eating with his other hand (Jones, 1924a, 1924b). Not only was Peter’s fear of the rabbit eliminated, but he also stopped being afraid of other furry objects, including the rat, cotton, and the fur coat (Watson, 1924).

For her pioneering efforts in the treatment of children’s fears, Jones is widely regarded as the first behavior therapist (Gieser, 1993; Rutherford, 2006).

SYSTEMATIC DESENSITIZATION AND EXPOSURE THERAPIES

Mary Cover Jones’s pioneering studies in treating children’s fears laid the groundwork for the later development of more standardized procedures to treat phobias and other anxiety disorders. Exposure therapy describes several techniques that have been recognized as effective treatments for anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). A person gradually and repeatedly relives a frightening experience under controlled conditions to help him overcome his fear of the dreaded object or situation and establish more adaptive beliefs and cognitions. Using a combination of behavioral and cognitive techniques, exposure therapy has a high rate of success in the treatment of anxiety disorders, PTSD, and OCD (McNally, 2007; Powers & others, 2010; Rosa-Alcázar & others, 2008).

exposure therapy

Behavioral therapy for phobias, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or related anxiety disorders in which the person is repeatedly exposed to the disturbing object or situation under controlled conditions.

One widely used type of exposure therapy, called systematic desensitization, was developed by South African psychiatrist Joseph Wolpe in the 1950s (Wolpe, 1958, 1982). Based on the same premise as counterconditioning, systematic desensitization involves learning a new conditioned response (relaxation) that is incompatible with or inhibits the old conditioned response (fear and anxiety).

systematic desensitization

A type of behavior therapy in which phobic responses are reduced by pairing relaxation with a series of mental images or real-life situations that the person finds progressively more fear-provoking; based on the principle of counterconditioning.

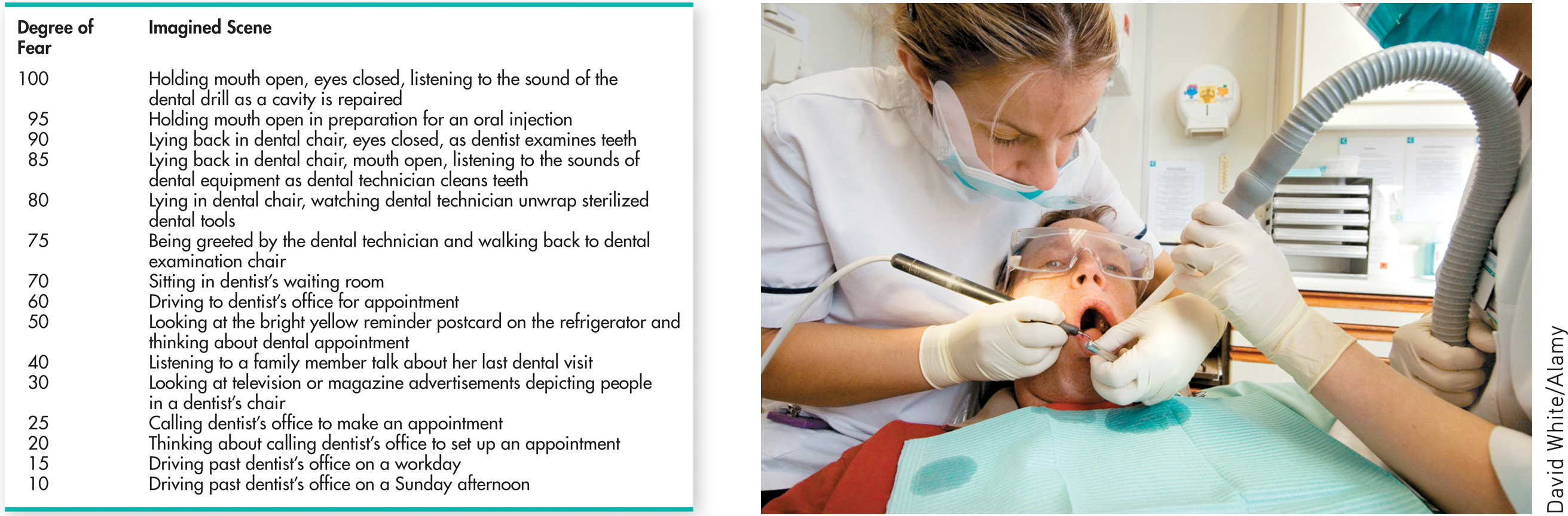

Three basic steps are involved in systematic desensitization. First, the patient learns progressive relaxation, which involves successively relaxing one muscle group after another until a deep state of relaxation is achieved. Second, the behavior therapist helps the patient construct an anxiety hierarchy, sometimes called an exposure hierarchy, which is a list of anxiety-provoking images associated with the feared situation, arranged in a hierarchy from least to most anxiety-producing (see FIGURE 15.1). The patient also develops an image of a relaxing control scene, such as walking on a secluded beach on a sunny day.

The third step involves the actual process of desensitization through exposure to feared experiences. While deeply relaxed, the patient imagines the least threatening scene on the anxiety hierarchy. After he can maintain complete relaxation while imagining this scene, he moves to the next. If the patient begins to feel anxiety or tension, the behavior therapist guides him back to imagining the previous scene or the control scene. If necessary, the therapist helps the patient relax again, using the progressive relaxation technique.

Over several sessions, the patient gradually and systematically works his way up the hierarchy, imagining each scene while maintaining complete relaxation. Once mastered with mental images, the desensitization procedure may be continued with exposure to the actual feared situation, which is called in vivo systematic desensitization. If the technique is successful, the feared situation no longer produces a conditioned response of fear and anxiety. The In Focus box “Using Virtual Reality to Conquer Phobias,” below, describes systematic desensitization using a “virtual reality” version of the actual feared situation.

In practice, systematic desensitization is often combined with other techniques, such as observational learning (Bandura, 2004b). Let’s consider a clinical example that combines systematic desensitization and observational learning. The client is Santiago, a 60-year-old man afraid of flying on airplanes. His behavior therapist first teaches Santiago progressive relaxation so he can induce relaxation in himself. Then, she and Santiago move through the anxiety hierarchy they had created. In Santiago’s case, the exposure hierarchy starts with imagining airplanes flying above high in the sky, then moves on to viewing pictures of airplanes at a distance, then viewing the interior of airplanes, and ultimately actually boarding an airplane and taking a flight. There were other, smaller steps in the hierarchy as well, to make sure Santiago could progress from step to step without too much of a “jump.”

!launch!

Santiago is able to move through the hierarchy by experiencing relaxation in conjunction with exposure to each consecutive stimulus that might have produced anxiety. Because relaxation and anxiety are incompatible, the relaxation essentially “blocks” Santiago’s anxiety about flying, just as Peter’s enjoyment of his milk and cookies blocked his anxiety about the rabbit. Another important aspect of the behavior therapist’s treatment of Santiago involves observational learning: She shows Santiago videos of people calmly boarding and riding on planes. Together, systematic desensitization and observational learning help Santiago overcome his phobia, and he is ultimately able to fly with minimal discomfort.

IN FOCUS

Using Virtual Reality to Treat Phobia and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Virtual reality (VR) therapy consists of computer-generated scenes that you view wearing goggles and a special motion-sensitive headset. Move your head in any direction and an electromagnetic sensor in the helmet detects the movement, and the computer-generated scene you see changes accordingly. Turning a handgrip lets you move forward or backward to explore your artificial world. You can also use a virtual hand to reach out and touch objects, such as an elevator button or a spider.

VR technology was first used in the treatment of specific phobias, including fear of flying, heights, spiders, driving, and enclosed places (Côté & Bouchard, 2008). In the virtual reality scene, patients are progressively exposed to the feared object or situation. For example, psychologist Ralph Lamson used virtual reality as a form of computer-assisted systematic desensitization to help more than 60 patients conquer their fear of heights. Rather than creating mental images, the person experiences computer-generated images that seem almost real. Once the goggles are donned, patients begin a 40-minute journey that starts in a café and progresses to a narrow wooden plank that leads to a bridge.

Although computer-generated and cartoonlike, the scenes of being high above the ground on the plank or bridge are real enough to trigger the physiological indicators of anxiety. Lamson encourages the person to stay in the same spot until the anxiety diminishes. Once relaxed, the person continues the VR journey. By the time the person makes the return journey back over the plank, heart rate and blood pressure are close to normal. After virtual reality therapy, over 90 percent of Lamson’s patients successfully rode a glass elevator up to the 15th floor.

Once experimental, virtual reality therapy has become an accepted treatment for specific phobias and is now being extended to other disorders, such as social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and acrophobia (Meyerbröker & Emmelkamp, 2010; Opris & others, 2012). One innovative application of VR therapy is in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in veterans of the wars in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan (McLay & others, 2011). Many PTSD patients are unable or unwilling to mentally re-create the traumatic events that caused their disorder, but the vivid sensory details of the “virtual world” encourage the patient to relive the experience in a controlled fashion.

For example, a young woman who suffered from severe PTSD after witnessing and barely escaping the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center was finally able to relive the events of the day through controlled, graduated exposure to a virtual reenactment of the events. Similarly, war veterans can be exposed to the sights and sounds of combat in a way that could not be accomplished in the “real world” of a therapist’s office or a busy downtown street. Marine veteran Joshua Musser was treated with virtual reality therapy after fighting in Iraq and developing PTSD. Musser told CNN (2011), “It put you back in Iraq where you kind of have one foot here and one foot there. The only thing outside of Iraq that you hear is [the clinical psychologist’s] voice, and so when she sees that I’m really starting to stress out … she would be in my ear and be pulling me back.”

VR therapy is easier and less expensive to administer than graduated exposure to the actual feared object or situation. Another advantage is that the availability of VR may make people who are extremely phobic more willing to seek treatment. In one survey of people who were phobic of spiders, more than 80 percent preferred virtual reality treatment over graduated exposure to real spiders (Garcia-Palacios & others, 2001). And, research suggests that patients will be less likely to refuse treatment or drop out of treatment with virtual exposure than with real-world exposure (Meyerbröker & Emmelkamp, 2010).

A newer form of exposure therapy for people suffering from traumatic memories has received a great deal of attention. Eye movement desensitization reprocessing, abbreviated EMDR, involves patients visually following the waving finger of a therapist while simultaneously holding a mental image of disturbing memories, events, or situations. Early research by its founder, psychologist Francine Shapiro, found that most patients experienced significant relief from their symptoms after just one EMDR therapy session (Shapiro, 1989a, 1989b, 2007). This was the beginning of what was to become one of the fastest-growing—and most lucrative—therapeutic techniques of the past decades (Herbert & others, 2000). Numerous studies have shown that patients experience relief from symptoms of anxiety after EMDR (see Davidson & Parker, 2001; Goldstein & others, 2000; Mills & Hulbert-Williams, 2012).

Yet, many elements of EMDR are similar to other treatment techniques, some of them well established and based on well-documented psychological principles. These similarities have led researchers to ask whether EMDR is more effective than exposure therapy or other cognitive-behavioral treatments. And the answer seems to be no. Not only is EMDR no more effective than standard treatments for anxiety disorders, including PTSD, it is actually less effective than exposure therapy for PTSD (Albright & Thyer, 2010; Davidson & Parker, 2001; Taylor & others, 2003; Verstrael & others, 2013). In addition, several studies found no difference between “real” EMDR and “sham” EMDR, a kind of placebo condition that removed the eye movements from the treatment (Davidson & Parker, 2001; Feske & Goldstein, 1997; Goldstein & others, 2000).

AVERSIVE CONDITIONING

The psychologist John Garcia first demonstrated how taste aversions could be classically conditioned (see Chapter 5). After rats drank a sweet-flavored water, Garcia injected them with a drug that made them ill. The rats developed a strong taste aversion for the sweet-flavored water, avoiding it altogether (Garcia & others, 1966). In much the same way, aversive conditioning attempts to create an unpleasant conditioned response to a harmful stimulus, such as cigarette smoking or alcohol consumption. For substance use disorder and addiction, taste aversions are commonly induced with the use of nausea-inducing drugs. For example, a medication called Antabuse is used in aversion therapy for alcoholism (Ellis & Dronsfield, 2013). Consuming alcohol while taking Anatabuse produces bouts of extreme, highly unpleasant nausea.

aversive conditioning

A relatively ineffective type of behavior therapy that involves repeatedly pairing an aversive stimulus with the occurrence of undesirable behaviors or thoughts.

Aversive conditioning techniques have been applied to a wide variety of problem behaviors (Cain & LeDoux, 2008). However, mental health professionals are typically very cautious about the use of such techniques, partly because of their potential to harm or produce discomfort for clients (C. B. Fisher, 2009; Francis, 2009). In addition, aversive techniques are generally not very effective (Emmelkamp, 2004).

Techniques Based on Operant Conditioning

B. F. Skinner’s operant conditioning model of learning is based on the simple principle that behavior is shaped and maintained by its consequences (see Chapter 5). Behavior therapists have developed several treatment techniques that are derived from operant conditioning. Shaping involves reinforcing successive approximations of a desired behavior. Shaping is often used to teach appropriate behaviors to patients who are mentally disabled by autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, or severe mental illness. For example, shaping has been used to increase the attention span of hospitalized patients with severe schizophrenia (Combs & others, 2011; Mueser & others, 2013).

Other operant conditioning techniques involve controlling the consequences that follow behaviors. Positive and negative reinforcement are used to increase the incidence of desired behaviors. Extinction, or the absence of reinforcement, is used to reduce the occurrence of undesired behaviors.

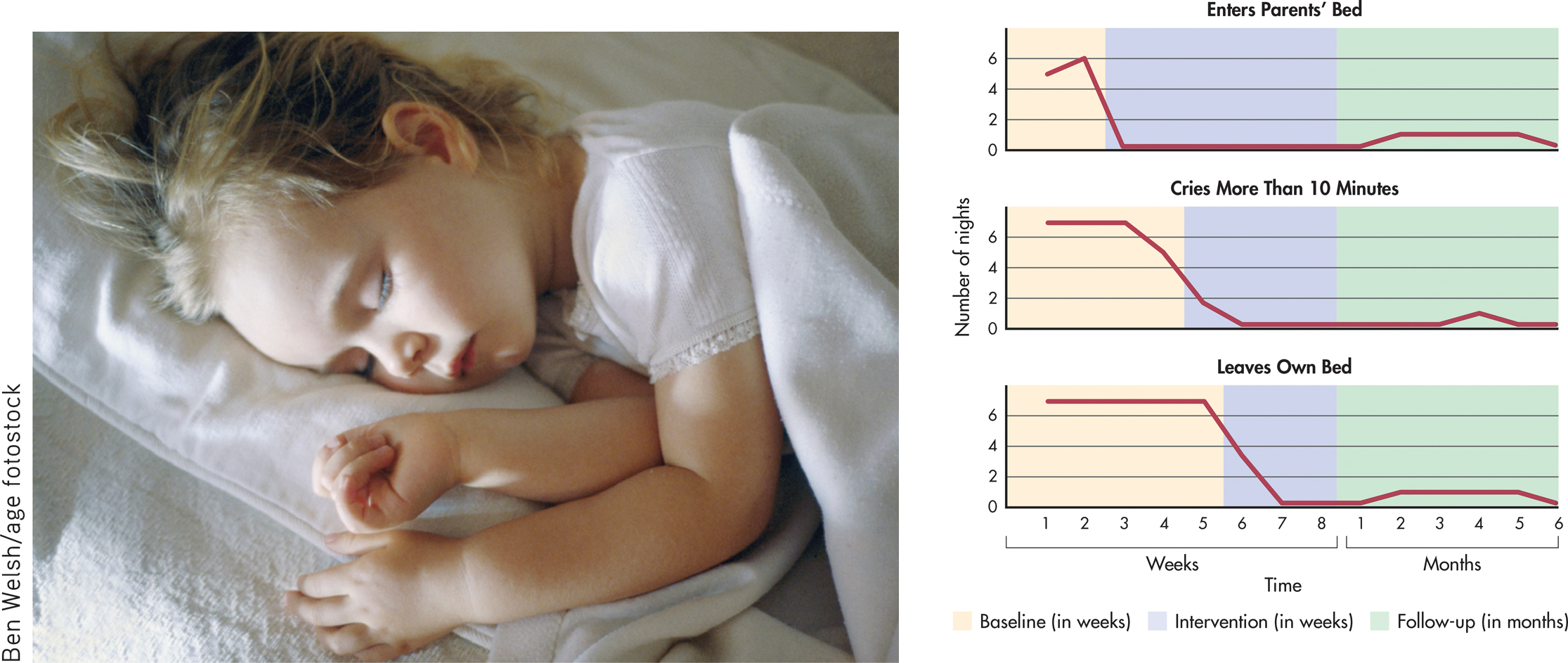

Let’s illustrate how operant techniques are used in therapy by describing a behavioral program to treat a 4-year-old girl’s sleeping problems (Ronen, 1991). The first step in the treatment program was to identify specific problem behaviors and determine their baseline rate, or how often each problem occurred before treatment began (see FIGURE 15.2). The baseline rate allowed the therapist to objectively measure the child’s progress. The parents next identified several very specific behavioral goals for their daughter. These goals included not crying when she was put to bed, not crying if she woke up in the night, not getting into her parents’ bed, and staying in her own bed throughout the night.

Ben Welsh/age fotostock

The parents were taught operant techniques to decrease the undesirable behaviors and increase desirable ones. For example, to extinguish the girl’s screaming and crying, the parents were taught to ignore the behavior rather than continue to reinforce it with parental attention. In contrast, desirable behaviors were to be positively reinforced with abundant praise, encouragement, social attention, and other rewards. FIGURE 15.2 shows the little girl’s progress for three specific problem behaviors.

Operant conditioning techniques have been applied to many different kinds of psychological problems, from habit and weight control to helping autistic children learn to speak and behave more adaptively.

The token economy is another example of the use of operant conditioning techniques to modify behavior. A token economy is a system for strengthening desired behaviors through positive reinforcement in a very structured environment. Basically, tokens or points are awarded as positive reinforcers for desirable behaviors and withheld or taken away for undesirable behaviors. The tokens can be exchanged for other reinforcers, such as special privileges.

token economy

A form of behavior therapy in which the therapeutic environment is structured to reward desired behaviors with tokens or points that may eventually be exchanged for tangible rewards.

Token economies have been most successful in controlled environments in which the behavior of the client is under ongoing surveillance or supervision. Thus, token economies have been used in classrooms, inpatient psychiatric units, and group homes (Field & others, 2004; Kamps & others, 2011; Kokaridas & others, 2013). Although effective, token economies are difficult to implement, especially in community-based outpatient clinics, so they are not in wide use today (R. P. Lieberman, 2000).

A modified version of the token economy has been used with outpatients in treatment programs called contingency management. Like the token economy, a contingency management intervention involves carefully specified behaviors that “earn” the individual concrete rewards. Unlike token economies, which cover many behaviors, contingency management strategies are typically more narrowly focused on one or a small number of specific behaviors (Prochaska & Norcross, 2014). Contingency management interventions have proved to be especially effective in the outpatient treatment of people who are dependent on heroin, cocaine, alcohol, or multiple drugs (Higgins & others, 2011; Tuten & others, 2012).

TABLE 15.3 summarizes key points about behavior therapy.

Behavior Therapy

| Type of Therapy | Founder | Source of Problems | Treatment Techniques | Goals of Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior therapy | Based on classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning | Learned maladaptive behavior patterns | Systematic desensitization, virtual reality, aversive conditioning, reinforcement and extinction, token economy, contingency management interventions, observational learning | To unlearn maladaptive behaviors and replace them with adaptive, appropriate behaviors |