15.5 Cognitive Therapies

KEY THEME

Cognitive therapies are based on the assumption that psychological problems are due to maladaptive thinking.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are rational-emotive behavior therapy and cognitive therapy, and how do they differ?

What are cognitive-behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based therapies?

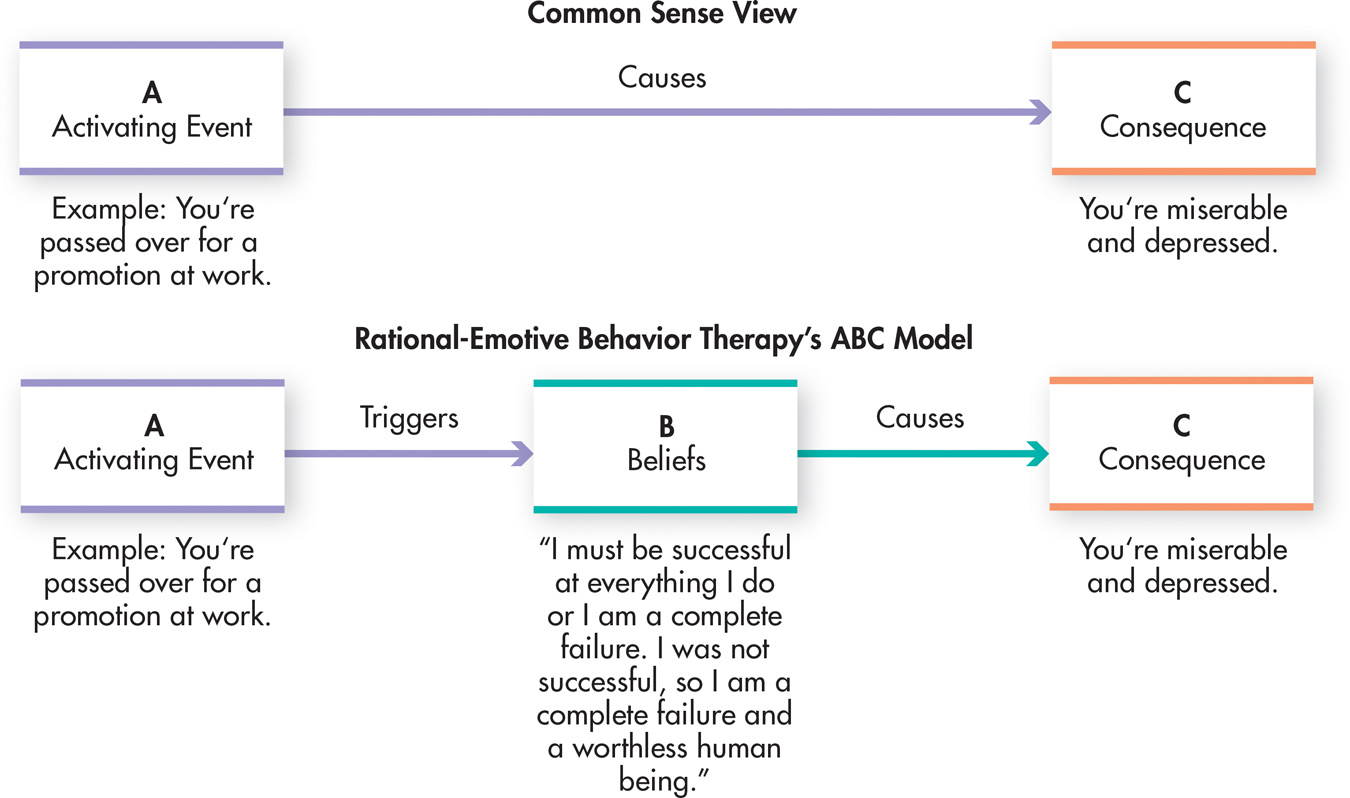

While behavior therapy assumes that faulty learning is at the core of problem behaviors and emotions, the cognitive therapies assume that the culprit is faulty thinking. The key assumption of the cognitive therapies could be put like this: Most people blame their unhappiness and problems on external events and situations, but the real cause of unhappiness is the way the person thinks about the events, not the events themselves. Thus, cognitive therapists zero in on the faulty, irrational patterns of thinking that they believe are causing the psychological problems. Once faulty, irrational patterns of thinking have been identified, the next step is to change them to more adaptive, healthy patterns of thinking. In this section, we’ll look at how this change is accomplished in two influential forms of cognitive therapy: Ellis’s rational-emotive behavior therapy (REBT) and Beck’s cognitive therapy (CT).

cognitive therapies

A group of psychotherapies based on the assumption that psychological problems are due to illogical patterns of thinking; treatment techniques focus on recognizing and altering these unhealthy thinking patterns.

Albert Ellis and Rational-Emotive Behavior Therapy

There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.

—William Shakespeare, Hamlet

Shakespeare said it more eloquently, but psychologist Albert Ellis has expressed the same sentiment: “You largely feel the way you think.” Ellis was trained as both a clinical psychologist and a psychoanalyst. As a practicing psychoanalyst, Ellis became increasingly disappointed with the psychoanalytic approach to solving human problems. Psychoanalysis simply didn’t seem to work: His patients would have insight after insight, yet never get any better.

In the 1950s, Ellis began to take a more active, directive role in his therapy sessions. He developed rational-emotive therapy, now called rational-emotive behavior therapy, and abbreviated REBT. It was renamed to acknowledge that REBT addresses behavior to some degree as well as thoughts. REBT is based on the assumption that “people are not disturbed by things but rather by their view of things” (Ellis, 1991; Ellis & Ellis, 2011). The key premise of REBT is that people’s difficulties are caused by their faulty expectations and irrational beliefs. Rational-emotive behavior therapy focuses on changing the patterns of irrational thinking that are believed to be the primary cause of the client’s emotional distress and psychological problems (Ellis, 2013).

rational-emotive behavior therapy (REBT)

A type of cognitive therapy, developed by psychologist Albert Ellis, that focuses on changing the client’s irrational beliefs.

Ellis points out that most people mistakenly believe that they become upset and unhappy because of external events. But Ellis (1993; Ellis & Ellis, 2011) would argue that it’s not external events that make people miserable—it’s their interpretation of those events. It’s not David’s behavior that’s really making Carrie miserable—it’s Carrie’s interpretation of the meaning of David’s behavior. In rational-emotive behavior therapy, psychological problems are explained by the “ABC” model, as shown in FIGURE 15.3. According to this model, when an Activating event (A) occurs, it is the person’s Beliefs (B) about the event that cause emotional Consequences (C).

Identifying the core irrational beliefs that underlie personal distress is the first step in rational-emotive behavior therapy. Often, irrational beliefs reflect “musts” and “shoulds” that are absolutes, such as the notion that “I should be competent at everything I do.” Other common irrational beliefs are listed in TABLE 15.4.

According to rational-emotive behavior therapy, unhappiness and psychological problems can often be traced to people’s irrational beliefs. Becoming aware of these irrational beliefs is the first step toward replacing them with more rational alternatives. Some of the most common irrational beliefs are listed to the left.

Irrational Beliefs

|

It is a dire necessity for you to be loved or approved of by virtually everyone in your community. You must be thoroughly competent, adequate, and achieving in all possible respects if you are to consider yourself worthwhile. Certain people are bad, wicked, or villainous, and they should be severely blamed and punished for their villainy. You should become extremely upset over other people’s wrongdoings. It is awful and catastrophic when things are not the way you would very much like them to be. Human unhappiness is externally caused, and you have little or no ability to control your bad feelings and emotions. It is easier to avoid than to face difficulties and responsibilities. Avoiding difficulties whenever possible is more likely to lead to happiness than facing difficulties. You need to rely on someone stronger than yourself. Your past history is an all-important determinant of your present behavior. Because something once strongly affected your life, it should indefinitely have a similar effect. You should become extremely upset over other people’s problems. There is a single perfect solution to all human problems, and it is catastrophic if this perfect solution is not found. |

| Source: Information from Ellis (1991). |

The consequences of such thinking are unhealthy negative emotions, like extreme anger, despair, resentment, and feelings of worthlessness. These kinds of irrational cognitive and emotional responses interfere with constructive attempts to change disturbing situations (Ellis & Ellis, 2011; O’Donohue & Fisher, 2009). According to REBT, the result is self-defeating behaviors, anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, and other psychological problems.

The next step in rational-emotive behavior therapy is for the therapist to vigorously dispute the irrational beliefs. In doing so, rational-emotive behavior therapists tend to be very direct and even confrontational (Ellis & Ellis, 2011). Rather than trying to establish a warm, supportive atmosphere, rational-emotive behavior therapists rely on logical persuasion and reason to push the client toward recognizing and surrendering his irrational beliefs (Dryden, 2008). According to Ellis (1991), blunt, harsh language is sometimes needed to push people into helping themselves. Understandably, this therapeutic environment can make REBT challenging for the client.

The long-term therapeutic goal of REBT is to teach clients to recognize and dispute their own irrational beliefs in a wide range of situations. However, responding “rationally” to unpleasant situations does not mean denying your feelings (Dryden 2009; Ellis & Bernard, 1985). Ellis believes that it is perfectly appropriate and rational to feel sad when you are rejected or regretful when you make a mistake. Appropriate emotions are the consequences of rational beliefs, such as “I would prefer that everyone like me, but that’s not likely to happen.” Such healthy mental and emotional responses encourage people to work toward constructively coping with difficult situations (Dryden & Branch, 2008; Ellis & Harper, 1975).

Albert Ellis was a colorful figure whose ideas have been extremely influential in psychotherapy (DeAngelis, 2007). Rational-emotive behavior therapy is a popular approach in clinical practice, partly because it is straightforward and simple. It has been shown to be generally effective in the treatment of major depressive disorder, social anxiety disorder, and certain anxiety disorders. Rational-emotive behavior therapy is also useful in helping people overcome self-defeating behaviors, such as an excessive need for approval, extreme shyness, and chronic procrastination (David & others, 2009; Ellis, 2013).

Aaron Beck and Cognitive Therapy

Like Albert Ellis, psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck was initially trained as a psychoanalyst. Beck’s development of cognitive therapy, abbreviated CT, grew out of his research on depression (Beck, 2004; Beck & others, 1979). Seeking to scientifically validate the psychoanalytic assumption that depressed patients “have a need to suffer,” Beck began collecting data on the free associations and dreams of his depressed patients. What he found, however, was that his depressed patients did not have a need to suffer. In fact, his depressed patients often went to great lengths to avoid being hurt or rejected by others.

cognitive therapy (CT)

Therapy developed by Aaron T. Beck that focuses on changing the client’s unrealistic and maladaptive beliefs.

Instead, Beck discovered that depressed people have an extremely negative view of the past, present, and future (Beck & others, 1979). Rather than realistically evaluating their situation, depressed patients have developed a negative cognitive bias, consistently distorting their experiences in a negative way. Their negative perceptions of events and situations are shaped by deep-seated, self-deprecating beliefs, such as “I can’t do anything right,” “I’m worthless,” or “I’m unlovable” (Beck, 1991). Beck’s cognitive therapy essentially focuses on correcting the cognitive biases that underlie major depressive disorder and other psychological disorders (see TABLE 15.5).

According to Aaron Beck, people with major depressive disorder perceive and interpret experience in very negative terms. They are prone to systematic errors in logic, or cognitive biases, which shape their negative interpretation of events. The table shows the most common cognitive biases in major depressive disorder.

Cognitive Biases in Depression

| Cognitive Bias (Error) | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Arbitrary inference | Drawing a negative conclusion when there is little or no evidence to support it | When Joan calls Jim to cancel their lunch date because she has an important meeting at work, Jim concludes that she is probably going out to lunch with another man. |

| Selective abstraction | Focusing on a single negative detail taken out of context and ignoring the more important aspects of the situation | During Kaori’s annual review, her manager praises her job performance but notes that she could be a little more confident when she deals with customers over the phone. Kaori leaves her manager’s office thinking that he is on the verge of firing her because of her poor telephone skills. |

| Overgeneralization | Drawing a sweeping, global conclusion based on an isolated incident and applying that conclusion to other unrelated areas of life | Tony spills coffee on his final exam. He apologizes to his instructor but can’t stop thinking about the incident. He concludes that he is a klutz who will never be able to succeed in a professional career. |

| Magnification and minimization | Grossly overestimating the impact of negative events and grossly underestimating the impact of positive events so that small, bad events are magnified, but good, large events are minimized | One week after Emily aces all her midterms, she worries about flunking out of college when she gets a B on an in-class quiz. |

| Personalization | Taking responsibility, blaming oneself, or applying external events to oneself when there is no basis or evidence for making the connection | Andrei becomes extremely upset when his instructor warns the class about plagiarism. He thinks the instructor’s warning was aimed at him, and he concludes that the instructor suspects him of plagiarizing parts of his term paper. |

| Source: Information from Beck & others (1979). | ||

Beck’s CT has much in common with Ellis’s rational-emotive behavior therapy. Like Ellis, Beck believes that what people think creates their moods and emotions. And like REBT, CT involves helping clients identify faulty thinking and replace unhealthy patterns of thinking with healthier ones.

But in contrast with Ellis’s emphasis on “irrational” thinking, Beck believes that major depressive disorder and other psychological problems are caused by distorted thinking and unrealistic beliefs (Hollon & Beck, 2004; Wright & others, 2011). Rather than logically debating the “irrationality” of a client’s beliefs, the CT therapist encourages the client to empirically test the accuracy of his or her assumptions and beliefs (Hollon & Beck, 2004; Wills, 2009). Let’s look at how this occurs in Beck’s CT.

The first step in CT is to help the client learn to recognize and monitor the automatic thoughts that occur without conscious effort or control. Whether negative or positive, automatic thoughts can control your mood and shape your emotional and behavioral reactions to events (Ingram & others, 2007). Because their perceptions are shaped by their negative cognitive biases, depressed people usually have automatic thoughts that reflect very negative interpretations of experience. Not surprisingly, the result of such negative automatic thoughts is a deepened sense of depression, hopelessness, and helplessness.

In the second step of CT, the therapist helps the client learn how to empirically test the reality of the automatic thoughts that are so upsetting. For example, to test the belief that “I always say the wrong thing,” the therapist might assign the person the task of initiating a conversation with three acquaintances and noting how often he actually said the wrong thing.

Initially, the CT therapist acts as a model, showing the client how to evaluate the accuracy of automatic thoughts. By modeling techniques for evaluating the accuracy of automatic thoughts, the therapist hopes to eventually teach the client to do the same on her own. The CT therapist also strives to create a therapeutic climate of collaboration that encourages the client to contribute to the evaluation of the logic and accuracy of automatic thoughts (Beck & others, 1979). This approach contrasts with the confrontational approach used by the REBT therapist, who directly challenges the client’s thoughts and beliefs.

Beck’s cognitive therapy has been shown to be effective in treating major depressive disorder and other psychological disorders, including anxiety disorders, borderline personality disorders, eating disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and relationship problems (Beck & Dozois, 2011; Butler & others, 2006; Dobson & Dobson, 2009; Gaudiano, 2008). Along with effectively treating major depressive disorder, cognitive therapy may also help prevent it from recurring, especially if clients learn and then use the skills they have learned in therapy. In one recent study, high-risk patients who had experienced several episodes of depression in the past were much less likely to relapse when they continued cognitive therapy after their depression had lifted (Beck & Alford, 2009). Beck’s cognitive therapy techniques have even been adapted to help treat psychotic symptoms, such as the delusions and disorganized thought processes that often characterize schizophrenia (Beck & others, 2009; van der Gaag & others, 2014). And, it can also improve motivation, self-confidence, and activity levels in people with schizophrenia (Grant & others, 2012; Turkington & Morrison, 2012).

TABLE 15.6 summarizes the key characteristics of Ellis’s rational-emotive behavior therapy and Beck’s cognitive therapy.

Comparing Cognitive Therapies

| Type of Therapy | Founder | Source of Problems | Treatment Techniques | Goals of Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rational-emotive behavior therapy (REBT) | Albert Ellis | Irrational beliefs | Very directive: Identify, logically dispute, and challenge irrational beliefs. | Surrender of irrational beliefs and absolutist demands |

| Cognitive therapy (CT) | Aaron T. Beck | Unrealistic, distorted perceptions and interpretations of events due to cognitive biases | Directive collaboration: Teach client to monitor automatic thoughts; test accuracy of conclusions; correct distorted thinking and perception. | Accurate and realistic perception of self, others, and external events |

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Mindfulness-Based Therapies

Although we’ve presented cognitive and behavioral therapies in separate sections, it’s important to note that cognitive and behavioral techniques are often combined in therapy. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (abbreviated CBT) refers to a group of psychotherapies that incorporate techniques from both approaches. CBT is based on the assumption that cognitions, behaviors, and emotional responses are interrelated (Hollon & Beck, 2004). Thus, changes in thought patterns will affect moods and behaviors, and changes in behaviors will affect thoughts and moods. Along with challenging maladaptive beliefs and substituting more adaptive cognitions, the therapist uses behavior modification, shaping, reinforcement, and modeling to teach problem solving and to change unhealthy behavior patterns.

cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)

Therapy that integrates cognitive and behavioral techniques and that is based on the assumption that thoughts, moods, and behaviors are interrelated.

The hallmark of cognitive-behavioral therapy is its pragmatic approach. Therapists design an integrated treatment plan, combining techniques from the behavioral and the cognitive approaches that are most appropriate for specific problems.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy has been used in the treatment of children, adolescents, and the elderly (Dautovich & Gunn, 2011; Kazdin, 2004; Weisz & Kazdin, 2010). Studies have shown that cognitive-behavioral therapy is a very effective treatment for many disorders, including major depressive disorder, eating disorders, substance use disorders, and anxiety disorders (Sheldon, 2011).

Cognitive-behavioral therapy can also help decrease the incidence of delusions and hallucinations in patients with schizophrenia and psychotic symptoms by teaching them how to test the reality of their mistaken beliefs and perceptions (Morrison & others, 2014; Wright & others, 2009). One man with schizophrenia, Peter Bullimore, described such therapy as making his voices seem less frightening. “My relationship with my voices has changed,” Bullimore reported. “It has woken me up to a new world” (Wilson, 2014). Variations of cognitive-behavioral therapy for schizophrenia have also been shown to improve cognitive functioning, such as attention and problem solving, and social skills (Bowie & others, 2014; Kurtz & Richardson, 2012; Wykes & others, 2011).

An emerging approach in cognitive-behavioral therapy involves the use of mindfulness techniques. These new therapies are called mindfulness-based interventions, mindfulness-based therapies, or mindfulness and acceptance therapies (Chiesa & Malinowski, 2011; Cullen, 2011). As discussed in Chapter 4 on consciousness and Chapter 13 on stress, health, and coping, mindfulness is a meditation technique that involves present-centered awareness without judgment (Hölzel & others, 2011). Contemporary mindfulness practices are based on Buddhist meditation techniques that originated over two thousand years ago.

Like traditional cognitive-behavioral therapy, the mindfulness-based therapies involve techniques that target both thoughts and behaviors. Unlike cognitive-behavioral therapy, however, mindfulness-based therapies do not seek to challenge, test, or replace the content of thoughts. Rather, the goal is to change the context in which those thoughts are understood (Hayes & others, 2011). That is, clients are taught to observe and change their relationship to maladaptive thoughts and emotions.

The ability to monitor thoughts and feelings without judgment ideally allows people to experience disturbing thoughts and feelings without reacting to them (Walsh, 2011). How? One important technique is called decentering (Bieling & others, 2012; Hayes & others, 2011). Individuals are taught to notice, label, and relate to their thoughts and emotions as “just passing events” rather than to identify with them and allow them to shape experience. By increasing mindful awareness of thoughts, impulses, cravings, and emotions, clients are less likely to act on them or be ruled by them.

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) was the first mindfulness-based therapy to earn broad acceptance. Developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn (2003, 2013), MBSR involves a structured program of mindfulness meditation, yoga and mindful body practices, and group discussion. The success of MBSR in the treatment of stress and anxiety helped spark the development of other mindfulness-based therapies targeted to specific disorders. For example, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) was developed to treat major depressive disorder, although it has been expanded to include other disorders (Coelho & others, 2013; Khoury & others, 2013; Segal & others, 2004, 2013). Mindfulness training has also been incorporated as a core element in other cognitive-behavioral treatments, including therapies designed to treat substance use disorder and borderline personality disorder (Hayes & others, 2011; Lynch & others, 2007).

Although a relatively new approach, the mindfulness-based therapies show promise. Two meta-analyses found that mindfulness-based approaches were effective treatments for depressive disorders, although results were mixed for anxiety disorders (S. Hofmann & others, 2010; Strauss & others, 2014). And, one large, carefully controlled study found that MBCT was as effective as antidepressant medications in preventing relapse after an acute episode of major depressive disorder (Bieling & others, 2012; Segal & others, 2010).