15.6 Group and Family Therapy

KEY THEME

Group therapy involves one or more therapists working with several clients simultaneously.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are some key advantages of group therapy?

What is family therapy, and how do its assumptions and techniques differ from those of individual therapy?

Individual psychotherapy offers a personal relationship between a client and a therapist, one that is focused on a single client’s problems, thoughts, and emotions. But individual psychotherapy has certain limitations. The therapist sees the client in isolation, rather than within the context of the client’s interactions with others. Hence, the therapist must rely on the client’s interpretation of reality and the client’s description of relationships with others. Group and family therapy provides the opportunity to overcome these limitations (Norcross & others, 2005; Schachter, 2011).

Group Therapy

Group therapy involves one or more therapists working with several people simultaneously. Group therapy may be provided by a therapist in private practice or at a community mental health clinic. Often, group therapy is an important part of the treatment program for hospital inpatients. Groups may be as small as 3 or 4 people, or as large as 10 or more people (Burlingame & McClendon, 2008).

group therapy

A form of psychotherapy that involves one or more therapists working simultaneously with a small group of clients.

Virtually any approach—psychodynamic, client-centered, behavioral, or cognitive—can be used in group therapy (Free, 2008; Tasca & others, 2011). And just about any problem that can be handled individually can be dealt with in group therapy (Garvin, 2011).

Group therapy has a number of advantages over individual psychotherapy. First, group therapy is very cost-effective: Because a single therapist can work simultaneously with several people, it is less expensive for the client and less time-consuming for the therapist. Second, rather than relying on a client’s self-perceptions about how she relates to other people, the therapist can observe her actual interactions with others. Observing the way clients interact with others in a group may provide unique insights into their personalities and behavior patterns. Sometimes, the group can serve as a microcosm of the client’s actual social life (Burlingame & others, 2004; Yalom, 2005).

Third, the support and encouragement provided by the other group members may help a person feel less alone and understand that his or her problems are not unique. For example, a team of family therapists set up group meetings with family members and co-workers of people who had died in the attacks on the World Trade Center (Boss & others, 2003). The therapists’ goals included helping the families come to terms with their loss, especially in cases where the bodies of their loved ones had not been recovered. One woman, who had lost dozens of co-workers, some of them close friends, explained the impact of the group sessions in this way:

As I saw the widows dealing with their loss, and believing it a bit more, it helped me to accept it even more. It was easier with sharing together. Strength in numbers. It makes you feel less alone. Out of the thousands of people you bump into, not everyone can understand what you’ve been through. If I am with any one of the families, I know they will understand what I am going through. We comfort each other. Even a blood sister might not understand as well.

Group therapies in the aftermath of other disasters, including Hurricane Katrina, have provided similar support (Salloum & others, 2009).

Fourth, group members may provide each other with helpful, practical advice for solving common problems and can act as models for successfully overcoming difficulties. Finally, working within a group gives people an opportunity to try out new behaviors in a safe, supportive environment (Yalom, 2005). For instance, someone who is very shy and submissive can practice more assertive behaviors and receive honest feedback from other group members.

Group therapy is typically conducted by a mental health professional. In contrast, self-help groups and support groups are typically conducted by nonprofessionals. Self-help groups and support groups have become increasingly popular in the United States and can be very helpful. As discussed in the In Focus box, “Increasing Access: Meeting the Need for Mental Healthcare,” the potential of these groups to promote mental health should not be underestimated.

IN FOCUS

Increasing Access: Meeting the Need for Mental Health Care

In the United States, more than two-thirds of people with mental illnesses in the general population go untreated, with even higher rates for African Americans and Hispanic Americans (Kazdin & Blase, 2011). And people are far less likely to get treatment in many other countries, particularly developing countries, where there are far fewer mental health clinicians (Jacob & Patel, 2014; Kazdin & Blase, 2011; Wang & others, 2011). Psychologists and other mental health clinicians have been working to address this problem. Some of the most interesting innovations in increasing access involve the use of clinicians without traditional training and technology-driven solutions.

Paraprofessionals and Lay Counselors

Clinicians who have not received traditional academic training are increasingly delivering mental health care. Worldwide, there are 40 million community health workers, paraprofessionals without extensive medical or psychological training (Rotheram-Borus & others, 2012). Paraprofessionals typically have some kind of training and may earn a certificate in their field, but they do not earn the licensure that a professional, such as a psychologist or licensed clinical social worker, has.

MYTH !lhtriangle! SCIENCE

Is it true that therapy is only effective if it is provided by a clinical psychologist or other highly trained therapist?

Lay counselors have even less training than paraprofessionals. For example, in a refugee camp in Uganda, Somali and Rwandan refugees with as little as a primary school education received brief training as lay counselors to serve other refugees with PTSD (Neuner & others, 2008). Following treatment, about 30% of their fellow refugees met the criteria for PTSD, as compared with more than 60% of those who were not treated.

The United States has relatively few mental health paraprofessionals (Rotheram-Borus & others, 2012). A lay counselor model exists, however, in many Latino communities in the United States which deploy minimally trained mental health care workers called promotoras into neighborhoods (Tran & others, 2013). Lay counselors are also used in the United States to provide online or telephone support—”hotlines”—for people who are thinking of suicide, have been sexually assaulted, or are trying to quit smoking. Several studies back the effectiveness of smoking “quitlines,” including their ability to reach underserved groups such as African Americans (Kazdin & Blase, 2011).

Self-Help Groups

Self-help groups offer another venue for mental health care delivery by nonprofessionals. The best-known self-help group is Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), which follows a twelve-step structure. The 12 steps of AA include themes of admitting that you have a problem, seeking help from a “higher power,” confessing your shortcomings, repairing your relationships with others, and helping other people who have the same problem. These 12 steps have been adapted by many different groups to fit their particular problem.

Just how helpful are self-help groups? Research has shown that self-help groups can be as effective as therapy provided by a mental health professional, at least for some psychological problems (Harwood & L’Abate, 2010). Because self-help groups are typically free, or charge just a nominal fee to cover materials, they may provide a cost-effective alternative for people who cannot afford or do not have access to psychotherapy (Kazdin & Blase, 2011).

Technology-Based Solutions

Research also supports the use of technological solutions to deliver mental and physical health care to underserved areas (Ben-Zeev, 2012; Teachman, 2014). When the technology involves computers or smart phones, this innovation is often called eHealth. Psychotherapy delivered via internet technology, such as Skype, is about as effective as face-to-face psychotherapy (Griffiths & others, 2010). Even the old-fashioned telephone has also been demonstrated to be effective, with the bonus of a far higher percentage of people completing treatment than with face-to-face therapy (Hammond & others, 2012; Mohr & others, 2008).

In some cases, technology allows the delivery of mental health treatment without the need for a therapist. Supportive emails or text messages, sent automatically, have been used for conditions ranging from smoking addiction to eating disorders (Bauer & others, 2003; Lenert & others, 2004). In one case, people with schizophrenia were sent more than 800 automatic text messages over several months (Granholm & others, 2012). For example, a text might ask, “What do you do to help cope with voices?” Patients who received these messages were more likely to take their medication regularly, had more social interactions, and had less severe hallucinations than those who did not receive the messages.

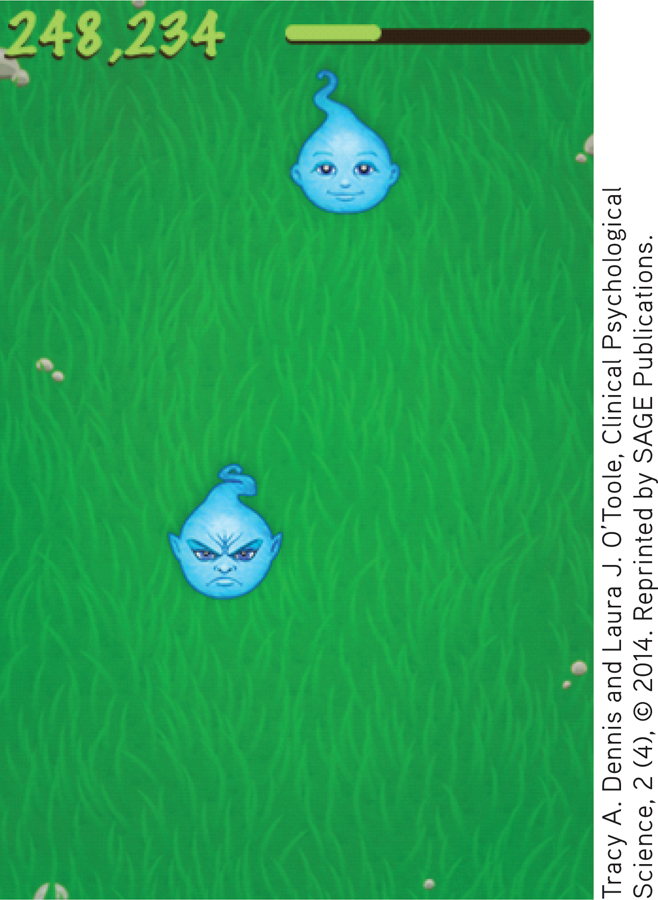

Researchers have also examined self-administered cognitive-behavioral therapies that use technology. One treatment, cognitive bias modification (CBM), targets anxiety (Eldar & others, 2012; Teachman, 2014). Patients play a game in which both threatening and non-threatening targets are presented—for example, cartoon characters with angry or friendly faces. To win, players learn to direct their attention to the nonthreatening target (Dennis & O’Toole, 2014; MacLeod & Mathews, 2012). Repeated play has been demonstrated to lead to decreases in symptoms of anxiety (MacLeod & Mathews, 2012).

Increased access to mental health care is an important goal. However, as the use of unconventional resources to deliver treatment increases, the field of psychology will face new challenges. First, just because treatment is available does not mean people in need will use it or that it will be effective (Kazdin & Rabbitt, 2013). And, new ethical considerations have arisen. For example, psychological organizations in many countries are developing ethical standards for those providing therapy by phone or Internet-based technologies (Barnett & Scheetz, 2003; Canadian Psychological Association, 2006). Grappling with the logistical and ethical issues of innovative ways to provide treatment is worth it, however, if access to much-needed care is expanded.

Family and Couple Therapy

Most forms of psychotherapy tend to see a person’s problems—and the solutions to those problems—as primarily originating within the individual himself. Family therapy operates on a different premise, focusing on the whole family rather than on an individual. The major goal of family therapy is to alter and improve the ongoing interactions among family members. Typically, family therapy involves many members of the immediate family, including children and adults, and may also include important members of the extended family, such as grandparents or in-laws (Nichols, 2012; Sexton & others, 2004).

family therapy

A form of psychotherapy that is based on the assumption that the family is a system and that treats the family as a unit.

Family therapy is based on the assumption that the family is a system, an interdependent unit, not just a collection of separate individuals. The family is seen as a dynamic structure in which each member plays a unique role. According to this view, every family has certain unspoken “rules” of interaction and communication. Some of these tacit rules revolve around issues such as which family members exercise power and how, who makes decisions, who keeps the peace, and what kinds of alliances members have formed among themselves. As such issues are explored, unhealthy patterns of family interaction can be identified and replaced with new “rules” that promote the psychological health of the family as a unit.

Family therapy is often used to enhance the effectiveness of individual psychotherapy. For example, patients with schizophrenia are less likely to experience relapses when family members are involved in therapy (Kopelowicz & others, 2007; O’Brien & others, 2014). In many cases, the therapist realizes that the individual client’s problems reflect conflict and disturbance in the entire family system (Smerud & Rosenfarb, 2011). For the client to make significant improvements, the family as a whole must become psychologically healthier. Family therapy is also indicated when there is conflict among family members or when younger children are being treated for behavior problems, such as truancy or aggressive behavior (Connell & others, 2007).

Many family therapists also provide marital or couple therapy (Bischoff, 2011). (The term couple therapy is preferred today because such therapy is conducted with any couple in a committed relationship, whether they are married or unmarried, heterosexual or homosexual). As is the case with family therapy, there are many different approaches to couple therapy (Lebow, 2008; Snyder & Balderrama-Durbin, 2012). For example, behavioral couple therapy is based on the assumption that couples are satisfied when they experience more reinforcement than punishment in their relationship. Thus, it focuses on increasing caring behaviors and teaching couples how to constructively resolve conflicts and problems. In general, most couple therapies have the goal of improving communication, reducing negative communication, and increasing intimacy between the pair.

CONCEPT REVIEW 15.1

Types of Psychotherapy

Match each statement below with one of the following types of psychotherapy:

Question

PLzJ/bwz3Yt+k+8SrZ3e8GMGauVqStG1fzXJVdP1j/Nw2ThBuwECS2co9t3FmP24HlGGcxazBsSxnAjjHS8KpKySKBydmGUCvoFnxWi9cgrz20KUI1fbVGfbwF7EmrwGqCzg76IiWTII42P7IbMc9Vcsh5437o4fHlTotK1NM13fry/3uX2eSvQv8tF3eIHc7unTFrJ6n/z3DrLXrdOyVJd5zBenCnsR6qhV+kgPVkUaXdiqfm8286eyATjDUaidr1HhfW5ZBTEKd5wgbV7CSjC8Dl/5yNM2nHYYVv/MsMgw+DJXXm0kMzYbrlwb7sLTZsdEsxuHGS2CKkGtMEujHluQ3rlCz3coRAj02cbTlBh35Ccyo9CTW1/I7lsmfD1JujX6EdWmw4l3S7DmmYHdfVpxu/76ByIDRKR7MTS/RFVMOoD5q4v46G6rNF5GWysX/PWywDLCgEGmdK4yOE300SYAgDTTr0oVeKdWTJRu/yfrzDGWG4RVrAY5odsyXoNQnCbwt+EnMtKzvo6bKTnB0kcNh8NfWkQ5Zg36oIaeQ9EXLJCEFC8qgrAG0f6uaF8A+2WRy8xvgMv6Z3u3d0voB8ze9eBIyfoa14k/+iYX4G6LK9y4JMcr+4Yy+Txxmn9rCyUYQoHbx22EXkwDSCCcJOBmZzGpCIFr9NEGv9rrnVU7UtwYhODZjWSTW/BEM6cvQZzFHNS9t6uHoVN6q8BxWU1aLi7MOUz7ruhS4d+Et2JBefZHW4kmUh3W0IK76Pnvv3SB/WdAW+1PX+VzyPf0XFGhKtHaFTciN+M9vvlKzQeHcocfm/ToL7k12/wwmCNe/fngE4C1jjcwvfmsHCrqytTCoe+72f8WTjb3OD++dArzre3jE/H09q7eC4PA6wq/zKoRwd5aW8r9K2akntkvGLhrWIeAlaQYO+ee8erdymqwgzFN0HVDmX2HViuLSeRKD3jBCG52XwzxqpUJqhRDmgX2f5NCH1k+Hdx++xEMNqwO7QjTX6ANvW8mpvNd+JqdLwhZWhzoDQW2OM/rsYNfFwrChWVaCiDsbdnumzy3hrnsiYH0YhdbEr1Lwwo/bn1s4BjG4QHCOLld4hsU29blxDZH1TPZk1i0TRM7plkjN7d85gVBcjrT6Kdys66HkDVjvyvpfdF6QtBtuSTPnkkT5YqTndrcS25H5/xm0Z0AjzZxeBct+TBcVgevtG19IiobdrrOgyLUsjSPLEE0X8WKJg0xYZji9qb6Ok55eu0aqFgYdvrJVCURgzTIqX4utb1mUmaqFLEoMIogExHkcLuCHXDusro=Test your understanding of Behavior, Cognitive, Group and Family Therapies with

.

.