15.7 Evaluating the Effectiveness of Psychotherapy

KEY THEME

Decades of research demonstrate that psychotherapy is effective in helping people with psychological disorders.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the common factors that contribute to successful outcomes in psychotherapy?

What is eclecticism?

Let’s start with a simple fact: Most people with psychological symptoms do not seek help from mental health professionals (Jagdeo & others, 2009; Kessler & others, 2004). Some people may be reluctant to seek treatment because of the stigma that is still associated with psychological problems (Pescosolido & others, 2013; Wahl, 2012). And, of course, not everyone has access to professional treatment (Kazdin & Blase, 2011). But many people eventually weather their psychological problems without professional intervention, sometimes seeking help and support from friends and family. And some people eventually improve simply with the passage of time, a phenomenon called spontaneous remission. Does psychotherapy offer significant benefits over just waiting for the possible “spontaneous remission” of symptoms?

The basic strategy for investigating this issue is to compare people who enter psychotherapy with a carefully selected, matched control group of people who do not receive psychotherapy (Freeman & Power, 2007; Nezu & Nezu, 2008). During the past half-century, hundreds of such studies have investigated the effectiveness of the major forms of psychotherapy (Cooper, 2008; Nathan & Gorman, 2007). To combine and interpret the results of such large numbers of studies, researchers have used a statistical technique called meta-analysis. Meta-analysis involves pooling the results of several studies into a single analysis, essentially creating one large study that can reveal overall trends in the data.

When meta-analysis is used to summarize studies that compare people who receive psychotherapy treatment to no-treatment controls, researchers consistently arrive at the same conclusion: Psychotherapy is significantly more effective than no treatment. On average, the person who completes psychotherapy treatment is better off than about 80 percent of those in the untreated control group (Cooper, 2008; Lambert & Ogles, 2004).

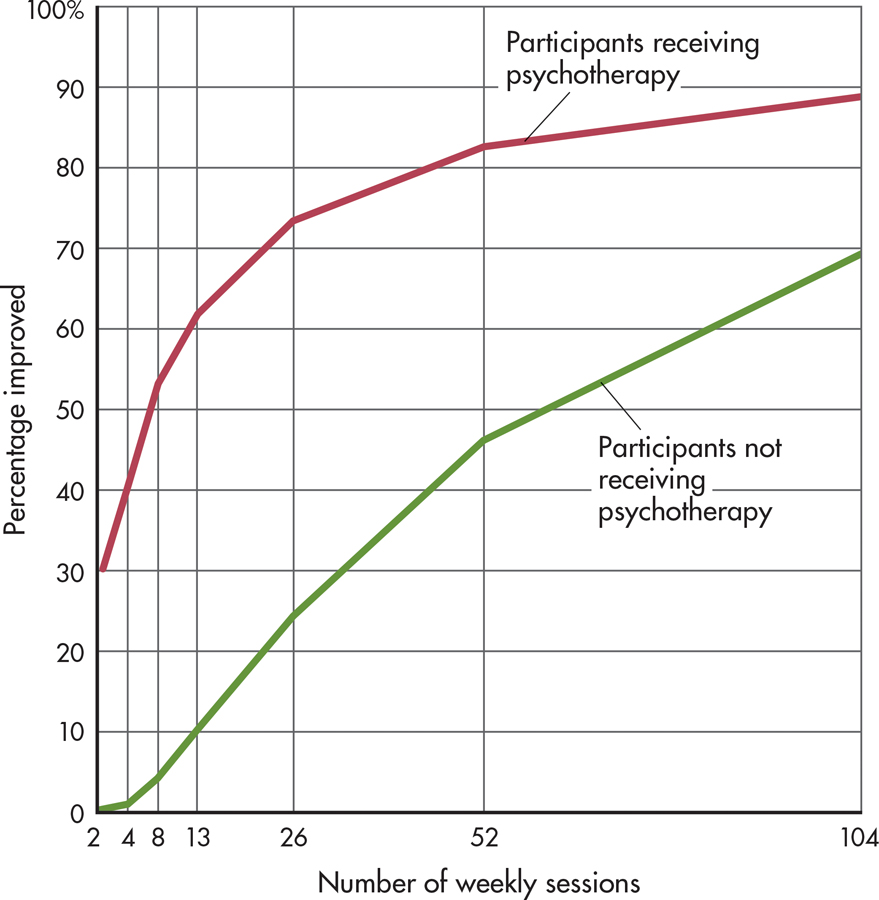

The benefits of psychotherapy usually become apparent in a relatively short time. As shown in FIGURE 15.4, approximately 50 percent of people show significant improvement by the eighth weekly session of psychotherapy. By the end of six months of weekly psychotherapy sessions, about 75 percent are significantly improved (Baldwin & others, 2009; Lambert & others, 2001).

The gains that people make as a result of psychotherapy also tend to endure long after the therapy has ended, sometimes for years (Lambert & Ogles, 2004; Shedler, 2010). Even brief forms of psychotherapy tend to produce beneficial and long-lasting changes (Beck, 2011; Shapiro & others, 2003). And, multiple meta-analyses have found that individual and group therapy are equally effective in producing significant gains in psychological functioning (Burlingame & others, 2004; Cuijpers & others, 2008).

Brain imaging technologies are providing another line of evidence demonstrating the power of psychotherapy to bring about change for people with many psychological disorders (Barsaglini & others, 2014; Karlsson, 2011). In one study, PET scans were used to measure brain activity before and after 10 weeks of therapy for obsessive–

Similarly, PET scans of patients with major depressive disorder show changes in brain functioning toward more normal levels after 12 weeks of interpersonal therapy (Martin & others, 2001). In other words, psychotherapy alone produces distinct physiological changes in the brain—changes that are associated with a reduction in symptoms (Arden & Linford, 2009; Karlsson, 2011).

Nevertheless, it’s important to note that psychotherapy is not a miracle cure. While most people experience significant benefits from psychotherapy, not everyone benefits to the same degree. Some people who enter psychotherapy improve only slightly or not at all. Others drop out early, presumably because therapy wasn’t working as they had hoped (Barrett & others, 2008). And in some cases, people get worse despite therapeutic intervention (Boisvert & Faust, 2003; Linden, 2013).

Is One Form of Psychotherapy Superior?

Given that the major types of psychotherapy use different assumptions and techniques, does one type of psychotherapy stand out as more effective than the others? In some cases, one type of psychotherapy is more effective than another in treating a particular problem (Barlow & others, 2013; Budd & Hughes, 2009). For example, cognitive therapy and interpersonal therapy are effective in treating major depressive disorders (Craighead & others, 2007). Cognitive, cognitive-behavioral, and behavior therapies tend to be more successful than insight-oriented therapies in helping people who are experiencing panic disorder, obsessive–

However, when meta-analysis techniques are used to assess the collective results of treatment outcome studies, a surprising but consistent finding emerges: In general, there is little or no difference in the effectiveness of different psychotherapies. Despite sometimes dramatic differences in psychotherapy techniques, all of the standard psychotherapies have very similar success rates (Cooper, 2008; Luborsky & others, 2002; Wampold, 2001). For example, one meta-analysis examined seven different types of psychotherapy for depression (Barth & others, 2013). All seven were more effective than a control group in which patients received no therapy, and the seven were fairly similar in their effectiveness in reducing symptoms of depression.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that the different types of psychotherapy generally have similar results?

One important qualification must be made at this point. In this chapter, we’ve devoted considerable time to explaining four major approaches to therapy: psychoanalytic and psychodynamic therapy; humanistic therapy; behavior therapy; and cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies. While distinct, all of these psychotherapy approaches have in common the fact that they are empirically supported treatments. In other words, they are based on known psychological principles, have been subjected to controlled scientific trials, and have demonstrated their effectiveness in helping people with psychological problems (David & Montgomery, 2011).

In contrast, one ongoing issue in contemporary psychotherapy is the proliferation of untested psychotherapies (Barlow & others, 2013). The fact that there is little difference in outcome among the empirically supported therapies does not mean that any and every form of psychotherapy is equally effective (Dimidjian & Hollon, 2010; Herbert & others, 2000). Too often, untested therapy techniques are heavily marketed and promoted, promising miraculous cures with little or no empirical research to back up their claims (Lazarus, 2000; Lilienfeld, 2007).

Psychologist James D. Herbert and his colleagues (2000) argue that before being put into widespread use, new therapies should provide empirically based answers to the following questions:

Does the treatment work better than no treatment?

Does the treatment work better than a placebo?

Does the treatment work better than standard treatments?

Does the treatment work through the processes that its proponents claim?

Often, “revolutionary” new therapies are developed, advertised, and marketed directly to the public—and to therapists—before controlled scientific studies of their effectiveness have been conducted (Lazarus, 2000). Many of the untested therapies are ineffective or, as in the case of EMDR discussed on pages 628–

What Factors Contribute to Effective Psychotherapy?

How can we explain the fact that different forms of psychotherapy are basically equivalent in producing positive results? One possible explanation is that the factors that are crucial to producing improvement are present in all effective therapies. Researchers have identified a number of common factors that are related to a positive therapy outcome (Bjornsson, 2011; Laska & others, 2013; Sparks & others, 2008).

First and most important is the quality of the therapeutic relationship (Cooper, 2008; Norcross & Lambert, 2011; Norcross & Wampold, 2011a). When psychotherapy is helpful, the therapist–

Second, certain therapist characteristics are associated with successful therapy. Helpful therapists have a caring attitude and the ability to listen empathically. They are genuinely committed to their clients’ welfare (Aveline, 2005). Regardless of approach, they tend to be warm, sensitive, and responsive people, and they are perceived as sincere and genuine (Beutler & others, 2004). Interestingly, however, years of experience as a therapist is not associated with successful therapy (Tracey & others, 2014). Researchers speculate that experience does not lead clinicians to perform better because there is no structure to provide them with ongoing feedback about their patients’ improvement.

Third, client characteristics are important (Clarkin & Levy, 2004; Knerr & others, 2011). If the client is motivated, committed to therapy, and actively involved in the process, a successful outcome is much more likely (Tallman & Bohart, 1999). Emotional and social maturity and the ability to express thoughts and feelings are important. Clients who are optimistic, who expect psychotherapy to help them with their problems, and who don’t have a previous history of psychological disorders are more likely to benefit from therapy (Leon & others, 1999). Finally, external circumstances, such as a stable living situation and supportive family members, can enhance the effectiveness of therapy.

Effective therapists are also sensitive to the cultural differences that may exist between themselves and their clients (Smith & others, 2011; Sue & Sue, 2008b). As described in the Culture and Human Behavior box below, cultural differences can be a barrier to effective psychotherapy. Increasingly, training in cultural sensitivity and multicultural issues is being incorporated into psychological training programs in the United States (Sammons & Speight, 2008).

Notice that none of these factors are specific to any particular brand of psychotherapy. However, this does not mean that differences between psychotherapy techniques are completely irrelevant. Rather, it’s important that there be a good “match” between the person seeking help and the specific psychotherapy techniques used (Norcross & Wampold, 2011b). One person may be very comfortable with psychodynamic techniques, such as exploring childhood memories and free association. Another person might be more open to behavioral techniques, like systematic desensitization. For therapy to be optimally effective, the individual should feel comfortable with both the therapist and the therapist’s approach to therapy.

Increasingly, such a personalized approach to therapy is being facilitated by the movement of mental health professionals toward eclecticism—the pragmatic and integrated use of diverse psychotherapy techniques (Hollanders, 2007; Lambert & others, 2004). Today, therapists identify themselves as eclectic more often than any other approach (Norcross & others, 2005; Lambert & Ogles, 2004). Eclectic psychotherapists carefully tailor the therapy approach to the problems and characteristics of the person seeking help. For example, an eclectic therapist might integrate insight-oriented techniques with specific behavioral techniques to help someone suffering from extreme shyness. A related approach is integrative psychotherapy. Integrative psychotherapists also use multiple approaches to therapy, but they tend to blend them together rather than choosing different approaches for different clients (Lazarus, 2008; Stricker & Gold, 2008).

eclecticism

(ih-KLEK-tih-siz-um) The pragmatic and integrated use of techniques from different psychotherapies.

CULTURE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

Cultural Values and Psychotherapy

The goals and techniques of many established approaches to psychotherapy tend to reflect European and North American cultural values (McGoldrick & others, 2005; T. B. Smith & others, 2011). In this box, we’ll look at how those cultural values can clash with the values of clients from other cultures, diminishing the effectiveness of psychotherapy.

A Focus on the Individual

In Western psychotherapy, the client is usually encouraged to become more assertive, more self-sufficient, and less dependent on others in making decisions. Problems are assumed to have an internal cause and are expected to be solved by the client alone. Therapy emphasizes meeting the client’s individual needs, even if those needs conflict with the demands of significant others. In collectivistic cultures, however, the needs of the individual are much more strongly identified with the needs of the group to which he or she belongs (Brewer & Chen, 2007; Pedersen & others, 2008; Sue & Sue, 2008a, b).

For example, traditional Native Americans are less likely than European Americans to believe that personal problems are due to an internal cause within the individual (Garrett, 2008). Instead, one person’s problems may be seen as a problem for the entire community to resolve.

In traditional forms of Native American healing, family members, friends, and other members of the community may be asked to participate in the treatment or healing rituals. One type of therapy, called network therapy, is conducted in the person’s home and can involve as many as 70 members of the individual’s community or tribe (LaFromboise & others, 1993b).

Latino cultures, too, emphasize interdependence over independence. In particular, they stress the value of familismo—the importance of the extended family network. Because the sense of family is so central to Latino culture, some psychologists recommend that members of the client’s extended family, such as grandparents and in-laws, be actively involved in psychological treatment (Garza & Watts, 2010).

Many collectivistic Asian cultures also emphasize a respect for the needs of others (Lee & Mock, 2005). The Japanese psychotherapy called Naikan therapy is a good example of how such cultural values affect the goals of psychotherapy (Tanaka-Matsumi, 2004). According to Naikan therapy, being self-absorbed is the surest path to psychological suffering. Thus, the goal of Naikan therapy is to replace the focus on the self with a sense of gratitude and obligation toward others. Rather than talking about how his own needs were not met by family members, the Naikan client is asked to meditate on how he has failed to meet the needs of others. Naikan therapy can be done on an outpatient basis but is often completed over a week spent in seclusion (Sengoku & others, 2010).

The Importance of Insight

Psychodynamic, humanistic, and cognitive therapies all stress the importance of insight or awareness of an individual’s thoughts and feelings. But many cultures do not emphasize the importance of exploring painful thoughts and feelings in resolving psychological problems. For example, Asian cultures stress that mental health is enhanced by the avoidance of negative thinking. Hence, a depressed or anxious person in China and many other Asian countries would be encouraged to avoid focusing on upsetting thoughts (Kim & Park, 2008).

Intimate Disclosure Between Therapist and Client

Many Western psychotherapies are based on the assumption that the clients will disclose their deepest feelings and most private thoughts to their therapists. But in some cultures, intimate details of one’s personal life would never be discussed with a stranger. Asians are taught to disclose intimate details only to very close friends. For example, a young Vietnamese student of ours vowed never to return to see a psychologist she had consulted about her struggles with depression. The counselor, she complained, was too “nosy” and asked too many personal questions. In many cultures, people are far more likely to turn to family members or friends than they are to mental health professionals (Leung & Boehnlein, 2005).

The demands for emotional openness may also clash with cultural values. In Asian cultures, people tend to avoid the public expression of emotions and often express thoughts and feelings nonverbally. Native American cultures tend to value the restraint of emotions rather than the open expression of emotions (Garrett, 2006; LaFromboise & others, 1993b).

Recognizing the need for psychotherapists to become more culturally sensitive, the American Psychological Association has recommended formal training in multicultural awareness for all psychologists (Fouad & Arredondo, 2007; Tanaka-Matsumi, 2011). The APA (2003) has also published extensive guidelines for psychologists who provide psychological help to culturally diverse populations. Interested students can download a copy of the APA guidelines at www.apa.org/

CONCEPT REVIEW 15.2

Elements of Effective Psychotherapy

Identify each statement below as true or false.

Question 15.1

1. ______ Meta-analysis is the most effective psychoanalytic technique.

| A. |

| B. |

Question 15.2

2. ______ In general, psychotherapy is no more effective than talking with a friend.

| A. |

| B. |

Question 15.3

3. ______ Behavior therapy is the single most effective therapy available for all psychological disorders.

| A. |

| B. |

Question 15.4

4. ______ Because the principles of effective therapy are universal, cultural differences between clients and therapists have no impact on the effectiveness of psychotherapy.

| A. |

| B. |

Question 15.5

5. ______ Regardless of which form of therapy psychotherapists practice, the most effective therapists are perceived as warm, genuine, and sincere.

| A. |

| B. |

Question 15.6

6. ______ A client’s attitude toward therapy has minimal impact on therapy’s effectiveness.

| A. |

| B. |

Test your understanding of Evaluating the Effectiveness of Psychotherapy with

.

.