2.4 A Guided Tour of the Brain

KEY THEME

The brain is a highly complex, integrated, and dynamic system of interconnected neurons.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are neural pathways and why are they important?

What are functional and structural plasticity?

What is neurogenesis, and what is the evidence for its occurrence in the adult human brain?

The human brain produces in 30 seconds as much data as the Hubble Space Telescope has produced in its lifetime.

—Konrad Kording (2013)

Think about it: The most complex mass of matter in the universe sits right behind your eyes and between your two ears—your brain. Not even the Internet can match the human brain for speed and sophistication of information transmission. On average, the human brain represents only about 2 percent of the body’s weight, yet consumes 20 percent of the body’s energy.

In this part of the chapter, we’ll take you on a guided tour of the human brain. As your tour guides, our goal here is not to tell you everything that is known or suspected about the human brain. Such a endeavor would take stack of books rather than a single chapter in a college textbook. Instead, our first goal is to familiarize you with the basic organization and structures of the brain. Our second goal is to give you a general sense of how the brain works. In later chapters, we'll add to your knowledge of the brain as we discuss the brain's involvement in specific psychologicalprocesses.

To begin, it's important to note that the brain generally does not lend itself to simple explanations. One early, simplistic approach to mapping the brain is discussed in Science Versus Pseudoscience, "Phrenology: The Bumpy Road to Scientific Progress," below. Although we will identify the functions that seem to be associated with particular brain regions, always remember that specific functions seldom correspond nearly to a single, specific brain site.

Most psychological processes, especially complex ones, involve multiple brain structures and regions. Even seemingly simple tasks—such as carrying on a conversation, catching a ball, or watching a movie—involve the smoothly coordinated synthesis of information among many different areas of your brain (Turk-Browne, 2013). Thus, contrary to what some people claim, it’s not true that you “use only 10 percent of your brain.” Imagine how well you would function if you lost even a third of your brain tissue, much less 90 percent. As neuroscientist Barry Gordon (2008) observes, “we use virtually every part of the brain, and the brain is active almost all the time.” suspected about the human brain. Such an endeavor would take stacks of books rather than a single chapter in a college textbook. Instead, our first goal is to familiarize you with the basic organization and structures of the brain. Our second goal is to give you a general sense of how the brain works. In later chapters, we’ll add to your knowledge of the brain as we discuss the brain’s involvement in specific psychological processes.

To begin, it’s important to note that the brain generally does not lend itself to simple explanations. One early, simplistic approach to mapping the brain is discussed in Science Versus Pseudoscience, “Phrenology: The Bumpy Road to Scientific Progress,” below. Although we will identify the functions that seem to be associated with particular brain regions, always remember that specific functions seldom correspond neatly to a single, specific brain site.

SCIENCE VERSUS PSEUDOSCIENCE

Phrenology: The Bumpy Road to Scientific Progress

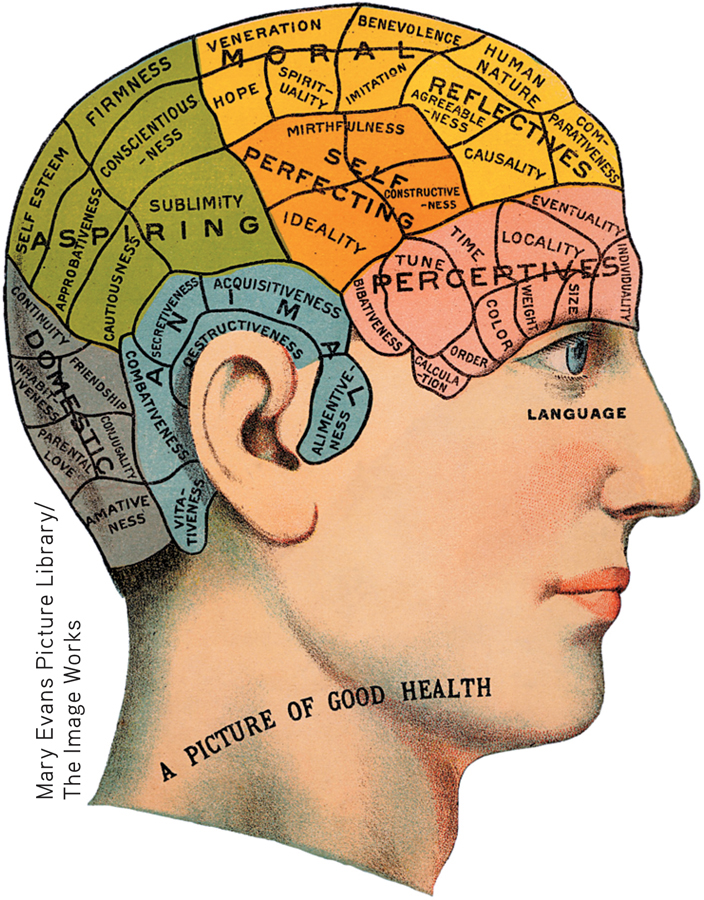

Are people with large foreheads smarter than people with small foreheads? Does the shape of your head provide clues to your personality? Such notions were at the core of phrenology, a popular pseudoscience founded in the 1800s by German physician Franz Gall.

phrenology

(freh-NAHL-uh-jee) A pseudoscientific theory of the brain that claimed that personality characteristics, moral character, and intelligence could be determined by examining the bumps on a person’s skull.

After studying the anatomy of human and animal brains, Gall became convinced that the size and shape of the cortex were reflected in the size and shape of the skull. Suspecting that variations in the size and shape of the human skull might reflect individual differences in abilities, character, and personality, he went to prisons, hospitals, and schools to study the association between personal characteristics and any distinctive bulges or bumps on the person’s skull. Eventually, Gall devised elaborate maps showing the location of the personality characteristics, or “faculties,” that he believed were reflected in the shape of the head (see image).

When Gall’s theory of phrenology was ridiculed by other scientists for lack of adequate evidence, Gall took his ideas to the general public. He lectured widely and gave “readings” in which he provided a personality description based on measuring the bumps on a person’s head. Phrenology continued to be popular with both physicians and the general public well into the 1900s (Sokal, 2001). At the height of phrenology’s popularity, some physicians even used leeches to drain blood from areas of the head that were believed to correspond to overdeveloped characteristics, such as “combativeness” or “amativeness” (McCoy, 2000).

Despite its pseudoscientific nature, phrenology helped advance the scientific study of the human mind and brain (Eghigian, 2011). It triggered scientific interest in the possibility of cortical localization, or localization of function—the idea that specific psychological and mental functions are located (or localized) in specific brain areas (Livianos-Aldano & others, 2007; van Wyhe, 2000).

cortical localization

The notion that different functions are located or localized in different areas of the brain; also called localization of function.

Today, sophisticated brain-imaging techniques like fMRI and PET scans have demonstrated that some cognitive and perceptual abilities are localized in different brain areas. So although Franz Gall and the phrenologists were wrong about the significance of bumps on the skull, they were on target about the general idea of cortical localization.

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

Mapping the Pathways of the Brain

The Human Connectome Project has an ambitious goal: to map the millions of miles of neural connections among the 100 billion neurons in the human brain (Sporns, 2011a, b). Launched in 2009 by the National Institutes of Health, the Human Connectome Project aims to combine brain-imaging data from hundreds of participants into a three-dimensional map of the brain’s information highways (Margulies & others, 2013).

A new brain-scanning technique called diffusion spectrum imaging (DSI) allows neuroscientists to produce three-dimensional images of the neural pathways that connect one part of the brain to another (Sporns, 2010; Wedeen & others, 2008). These pathways, sometimes called tracts, are made up of bundles of myelinated axons. DSI tracks the movement of water molecules in brain tissue along the axons.

To give you an idea of the complexity of the Connectome Project’s task, imagine a one-millimeter cube of brain tissue about the size of a grain of sugar. To store the images needed to form a picture of all of the neural connections in this tiny cube of brain tissue would require one petrobyte—one million gigabytes—of computer memory. And to put that figure in perspective, one petrobyte is roughly the amount of data space that Facebook uses to store 40 billion photos (Vance, 2010).

Each fiber in the photo represents hundreds of thousands of individual axons, which are too minuscule to be distinguished in a brain scan. Blue colors show the bundled axons that form the neural pathway stretching from the top to the bottom of the brain. Green represents pathways from the front (left) to the back (right) of the brain. Red shows the corpus callosum, the pathway between the right and left-brain hemispheres. (You’ll read about the corpus callosum later in the chapter.)

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that even simple behaviors and abilities involve the activation of multiple parts of the brain?

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that you only use 10% of your brain?

How is information communicated and shared among these multiple brain regions? Even though we’ll talk about brain centers and structures that are involved in different aspects of behavior, the best way to think of the brain is as an integrated system.

Many brain functions involve the activation of neural pathways that link different brain structures (Jbabdi & Behrens, 2012; Park & Friston, 2013). Neural pathways are formed by groups of neuron cell bodies in one area of the brain that project their axons to other brain areas (Seung, 2012). These neural pathways form communication networks and circuits that link different brain areas. Mapping the information highways of the human brain is the ambitious goal of The Human Connectome Project, which is described in the Focus on Neuroscience above.

The Dynamic Brain

PLASTICITY AND NEUROGENESIS

One of the great conceptual leaps of modern neuroscience has been the notion of neuroplasticity. … Scientists now know that even modest changes in the internal or external world can lead to structural changes in the brain.

—Barry L. Jacobs (2004)

Before embarking on our tour, we need to describe one last important characteristic of the brain: its remarkable capacity to change in response to experience. Until the mid-1960s, neuroscientists believed—and taught—that by early adulthood the brain’s physical structure was hard-wired or fixed for life. But today it’s known that the brain’s physical structure is literally sculpted by experience (Knobloch & Jessberger, 2011). The brain’s ability to change function and structure is referred to as neuroplasticity, or simply plasticity. (The word plastic originally comes from a Greek word, plastikos, which means the quality of being easily shaped or molded.)

One form of plasticity is functional plasticity, which refers to the brain’s ability to shift functions from damaged to undamaged brain areas. Depending on the location and degree of brain damage, stroke or accident victims often need to “relearn” once-routine tasks like speaking, walking, or reading. If the rehabilitation is successful, undamaged brain areas gradually assume the ability to process and execute the tasks (Pascual-Leone & others, 2005).

functional plasticity

The brain’s ability to shift functions from damaged to undamaged brain areas.

But the brain can do more than just shift functions from one area to another. Structural plasticity refers to the brain’s ability to physically change its structure in response to learning, active practice, or environmental stimulation. It is now known that even subtle changes in your environment or behavior can lead to structural changes in the brain (Bryck & Fisher, 2012; Jacobs, 2004). In the Focus on Neuroscience, “Juggling and Brain Plasticity,” below, we describe an ingenious experiment that dramatically demonstrated structural plasticity in the human brain.

structural plasticity

The brain’s ability to change its physical structure in response to learning, active practice, or environmental influences.

An even more dramatic example of the brain’s capacity to change is neurogenesis—the development of new neurons. For many years, scientists believed that people and most animals did not experience neurogenesis after birth (Kempermann, 2012a). With the exception of birds, tree shrews, and some rodents, it was thought that the mature brain could lose neurons but could not grow new ones. But new studies offered compelling evidence that challenged that dogma.

neurogenesis

The development of new neurons.

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

Juggling and Brain Plasticity

What happens to the brain when you learn a new, challenging skill? Does learning affect the brain’s physical structure?

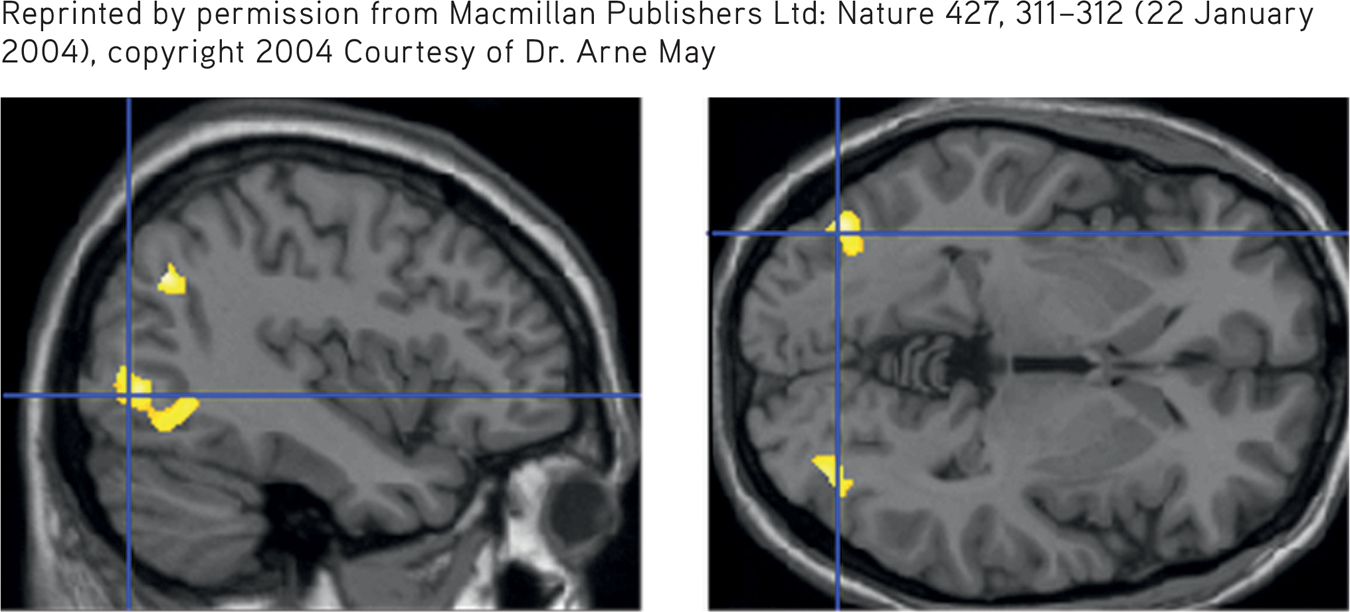

German researcher Bogdan Draganski and his colleagues (2004, 2006) showed that learning a new skill produces structural changes in the human brain. In their study, 24 young adults were assigned to either a “jugglers” or “nonjugglers” group. A baseline MRI scan indicated that there were no significant regional brain differences between the two groups at the beginning of the study.

Then the juggling group members were given three months to master a basic juggling routine. A second brain scan taken after this period indicated that the jugglers showed a 3 to 4 percent increase in gray matter in two brain regions that are involved in perceiving, remembering, and anticipating complex visual motions.

These two regions are shown in yellow in the composite MRI scans shown on the right. In comparison, there were no brain changes in the scans of the nonjugglers over the same three-month period.

A third brain scan was performed three months after participants in the juggling group were told to stop practicing. Now, the same regions that had grown while the jugglers were practicing their skills every day had decreased in size. While still larger than before the participants had learned to juggle, the regions were 1 to 2 percent smaller than when the participants were juggling every day. In comparison, the same regions in the nonjuggling control group remained unchanged.

In a later study, novice jugglers showed changes in brain regions within just seven days after learning to juggle (Driemeyer & others, 2008). And, demonstrating the plasticity of even the aging brain, similar changes were found in a group of senior citizens after they learned to juggle (Boyke & others, 2008).

Wondering how long it might take for learning to translate into structural changes in the brain? A new study by Yaniv Sagi and his colleagues (2012) detected tiny structural changes in the hippocampus after study participants spent just two hours playing a new video game that involved spatial learning and memory.

We’ve always known that our brains control our behavior, but not that our behavior could control and change the structure of our brains.

—Fred Gage (2007)

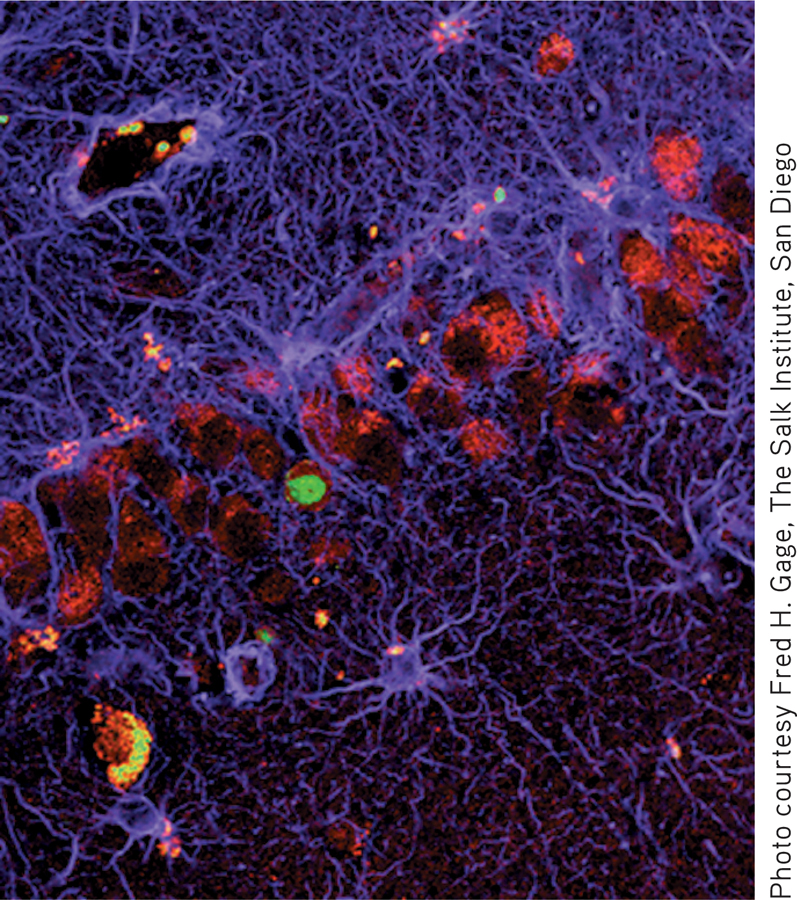

First, research by psychologist Elizabeth Gould and her colleagues (1998) showed that adult marmoset monkeys were generating a significant number of new neurons every day in the hippocampus, a brain structure that plays a critical role in the ability to form new memories. Gould’s groundbreaking research provided the first demonstration that new neurons could develop in an adult primate brain. Could it be that the human brain also has the capacity to generate new neurons in adulthood?

Researchers Peter Eriksson, Fred Gage, and their colleagues (1998) provided the first evidence that it does. The subjects were five adult cancer patients, whose ages ranged from the late fifties to the early seventies. These patients were all being given a drug used in cancer treatments to determine whether tumor cells are multiplying. The drug is incorporated into newly dividing cells, coloring them. Using fluorescent lights, this chemical tracer can be detected in the newly created cells. Eriksson and Gage reasoned that if new neurons were being generated, the drug would be present in their genetic material.

Within hours after each patient died, an autopsy was performed and the hippocampus was removed and examined. The results were unequivocal. In each patient, hundreds of new neurons had been generated since the drug had been administered, even though all the patients were over 50 years old (see accompanying photo).

Some neuroscientists were still skeptical, but an ingenious new study provides definitive proof of neurogenesis in the adult human brain. Swedish neuroscientist Kirsty Spalding and her colleagues (2013) used carbon dating to measure the growth of new neurons in the brains of people aged 19 to 92. More than 50 years ago, aboveground testing of nuclear bombs released carbon-14, or C-14, into the atmosphere. Since these nuclear tests were banned in 1963, levels of C-14 in the atmosphere have declined at a regular and well-known rate. Measuring the amount of C-14 concentration in neurons therefore provided a “time-stamp” for the neurons, allowing researchers to determine when the neurons had been generated.

The carbon-14 signature was unmistakable: Spalding and her colleagues found clear evidence of neurogenesis after birth and, in fact, throughout the lifespan. They were also able to calculate the rate of neurogenesis in a specific region of the brain, called the hippocampus, a brain region involved in learning and memory. It turned out that an average of 1,400 new neurons were being generated each day. The rate declined only slightly with age. Other regions of the brain, however, did not show evidence of neurogenesis.

Research on neurogenesis in humans and animals has uncovered a number of intriguing findings. It is now generally accepted that newborn neurons develop into mature functioning neurons in at least two regions of the human brain—the hippocampus and the olfactory bulb, responsible for odor perception (Lee & others, 2012). These newly generated neurons are incorporated into existing neural networks, possibly playing a key role in learning and memory (Kempermann, 2012b; Marin-Burgin & others, 2012). In nonhuman animals, such as macaque monkeys, newborn neurons migrate to multiple brain regions (Gould, 2007). Environmental factors also affect neurogenesis. Stress, exercise, environmental complexity, and even social status have been shown to influence the rate of neurogenesis in monkeys, rodents, and birds (Glasper & others, 2012).

In the next section, we’ll begin our guided tour of the brain. Following the general sequence of the brain’s development, we’ll start with the structures at the base of the brain and work our way up to more complicated brain regions, which are responsible for complex mental activity.

The Brainstem

HINDBRAIN AND MIDBRAIN STRUCTURES

KEY THEME

The brainstem includes the hindbrain and midbrain, located at the base of the brain.

KEY QUESTIONS

Why does damage to one side of the brain affect the opposite side of the body?

What are the key structures of the hindbrain and midbrain, and what are their functions?

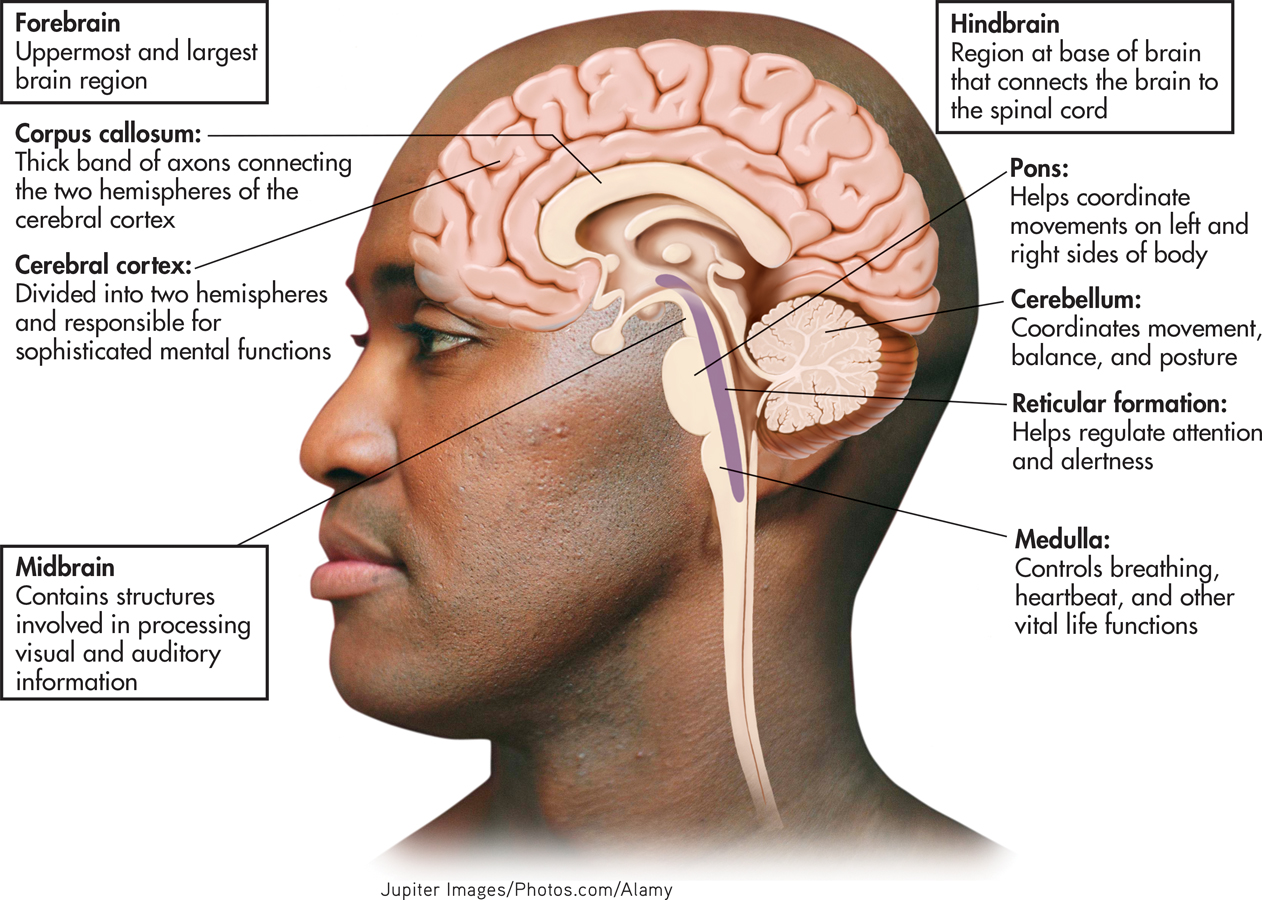

The major regions of the brain are illustrated in FIGURE 2.14, which can serve as a map to keep you oriented during our tour. At the base of the brain lie the hindbrain and, directly above it, the midbrain. Combined, the structures of the hindbrain and midbrain make up the brain region that is also called the brainstem.

brainstem

A region of the brain made up of the hindbrain and the midbrain.

THE HINDBRAIN

The hindbrain connects the spinal cord with the rest of the brain. Sensory and motor pathways pass through the hindbrain to and from regions that are situated higher up in the brain. Sensory information coming in from one side of the body crosses over at the hindbrain level, projecting to the opposite side of the brain. And outgoing motor messages from one side of the brain also cross over at the hindbrain level, controlling movement and other motor functions on the opposite side of the body. This is referred to as contralateral organization.

hindbrain

A region at the base of the brain that contains several structures that regulate basic life functions.

Contralateral organization accounts for why people who suffer strokes on one side of their brain experience muscle weakness or paralysis on the opposite side of their body. Our friend Asha, for example, suffered only minor damage to motor control areas in her brain. However, because the stroke occurred on the left side of her brain, what muscle weakness she did experience was localized on the right side of her body, primarily in her right hand.

Three structures make up the hindbrain—the medulla, the pons, and the cerebellum. The medulla is situated at the base of the brain directly above the spinal cord. It is at the level of the medulla that ascending sensory pathways and descending motor pathways crisscross to the contralateral side of the body.

medulla

(muh-DOOL-uh) A hindbrain structure that controls vital life functions such as breathing and circulation.

The medulla plays a critical role in basic life-sustaining functions. It contains centers that control such vital autonomic functions as breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure. The medulla also controls a number of vital reflexes, including swallowing, coughing, vomiting, and sneezing. Because the medulla is involved in such critical life functions, damage to this brain region can rapidly prove fatal.

Above the medulla is a swelling of tissue called the pons, which represents the uppermost level of the hindbrain. Bulging out behind the pons is the large cerebellum. On each side of the pons, a large bundle of axons connects it to the cerebellum. The word pons means “bridge,” and the pons is a bridge of sorts: Information from various other brain regions located higher up in the brain is relayed to the cerebellum via the pons. The pons also contains centers that play an important role in regulating breathing.

pons

A hindbrain structure that connects the medulla to the two sides of the cerebellum; helps coordinate and integrate movements on each side of the body.

cerebellum

(sair-uh-BELL-um) A large, two-sided hindbrain structure at the back of the brain; responsible for muscle coordination and maintaining posture and equilibrium.

The cerebellum functions in the control of balance, muscle tone, and coordinated muscle movements. It is also involved in the learning of habitual or automatic movements and motor skills, such as typing, writing, or backhanding a tennis ball.

Jerky, uncoordinated movements can result from damage to the cerebellum. Simple movements, such as walking or standing upright, may become difficult or impossible. The cerebellum is also one of the brain areas affected by alcohol consumption, which is why a person who is intoxicated may stagger and have difficulty walking a straight line or standing on one foot. (This is also why a police officer will ask a suspected drunk driver to execute these normally effortless movements.)

At the core of the medulla and the pons is a network of neurons called the reticular formation, or the reticular activating system, which is composed of many groups of specialized neurons that project up to higher brain regions and down to the spinal cord. The reticular formation plays an important role in regulating attention and sleep.

reticular formation

(reh-TICK-you-ler) A network of nerve fibers located in the center of the medulla that helps regulate attention, arousal, and sleep; also called the reticular activating system.

THE MIDBRAIN

The midbrain is an important relay station that contains centers involved in the processing of auditory and visual sensory information. Auditory sensations from the left and right ears are processed through the midbrain, helping you orient toward the direction of a sound. The midbrain is also involved in processing visual information, including eye movements, helping you visually locate objects and track their movements. After passing through the midbrain level, auditory information and visual information are relayed to sensory processing centers farther up in the forebrain region, which will be discussed shortly.

midbrain

The middle and smallest brain region, involved in processing auditory and visual sensory information.

A midbrain area called the substantia nigra is involved in motor control and contains a large concentration of dopamine-producing neurons. Substantia nigra means “dark substance,” and as the name suggests, this area is darkly pigmented. The substantia nigra is part of a larger neural pathway that helps prepare other brain regions to initiate organized movements or actions. In the section on neurotransmitters, we noted that Parkinson’s disease involves symptoms of abnormal movement, including difficulty initiating or starting a particular movement. Many of those movement-related symptoms are associated with the degeneration of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra.

substantia nigra

(sub-STAN-she-uh NYE-gruh) An area of the midbrain that is involved in motor control and contains a large concentration of dopamine-producing neurons.

The Forebrain

KEY THEME

The forebrain includes the cerebral cortex and the limbic system structures.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the four lobes of the cerebral cortex and their functions?

What is the limbic system?

What functions are associated with the thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus, and amygdala?

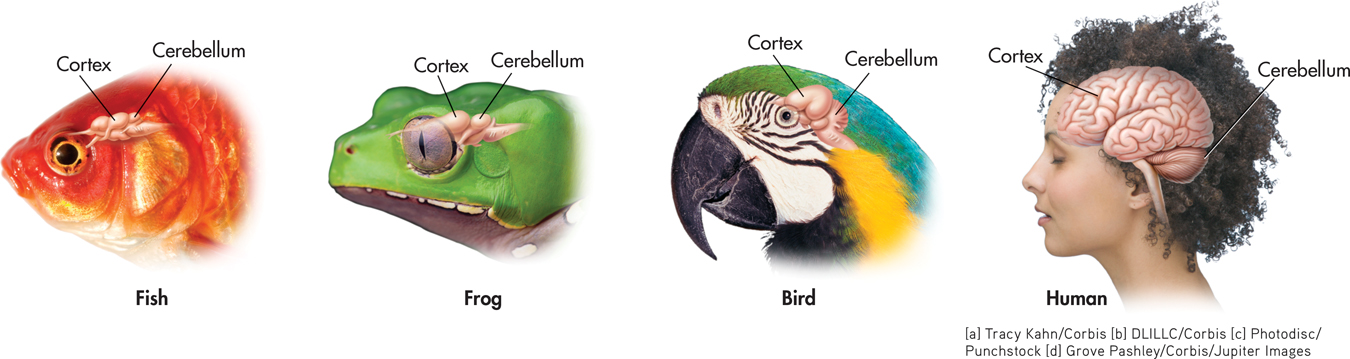

Situated above the midbrain is the largest region of the brain: the forebrain. In humans, the forebrain represents about 90 percent of the brain. In FIGURE 2.15, you can see how the size of the forebrain has increased during evolution, although the general structure of the human brain is similar to that of other species (Clark & others, 2001). Many important structures are found in the forebrain region, but we’ll begin by describing the most prominent—the cerebral cortex.

forebrain

The largest and most complex brain region, which contains centers for complex behaviors and mental processes; also called the cerebrum.

THE CEREBRAL CORTEX

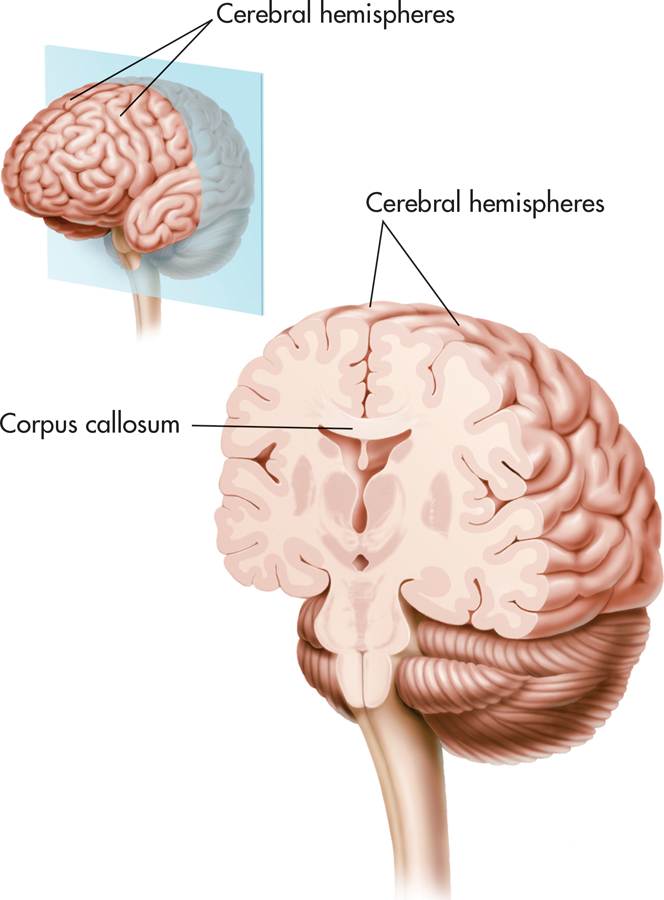

The outer portion of the forebrain, the cerebral cortex, is divided into two cerebral hemispheres. The word cortex means “bark,” and much like the bark of a tree, the cerebral cortex is the outer covering of the forebrain. A thick bundle of axons, called the corpus callosum, connects the two cerebral hemispheres, as shown in FIGURE 2.16. The corpus callosum serves as the primary communication link between the left and right cerebral hemispheres.

cerebral cortex

(suh-REE-brull or SAIR=uh-brull) The wrinkled outer portion of the forebrain, which contains the most sophisticated brain centers.

cerebral hemispheres

The nearly symmetrical left and right halves of the cerebral cortex.

corpus callosum

A thick band of axons that connects the two cerebral hemispheres and acts as a communication link between them.

The cerebral cortex is only about a quarter of an inch thick. It is mainly composed of glial cells and neuron cell bodies and axons, giving it a grayish appearance—which is why the cerebral cortex is sometimes described as being composed of gray matter. Extending inward from the cerebral cortex are white myelinated axons that are sometimes referred to as white matter. These myelinated axons connect the cerebral cortex to other brain regions.

Numerous folds, grooves, and bulges characterize the human cerebral cortex. The purpose of these ridges and valleys is easy to illustrate. Imagine a flat, three-foot by three-foot piece of paper. You can compact the surface area of this piece of paper by scrunching it up into a wad. In much the same way, the grooves and bulges of the cerebral cortex allow about three square feet of surface area to be packed into the small space of the human skull.

Look again at FIGURE 2.14 on page 65. The drawing of the human brain is cut through the center to show how the cerebral cortex folds above and around the rest of the brain. In contrast to the numerous folds and wrinkles of the human cerebral cortex, notice the smooth appearance of the cortex in fish, amphibians, and birds in FIGURE 2.15. Mammals with large brains—such as cats, dogs, and nonhuman primates—also have wrinkles and folds in the cerebral cortex, but to a lesser extent than humans (Jarvis & others, 2005).

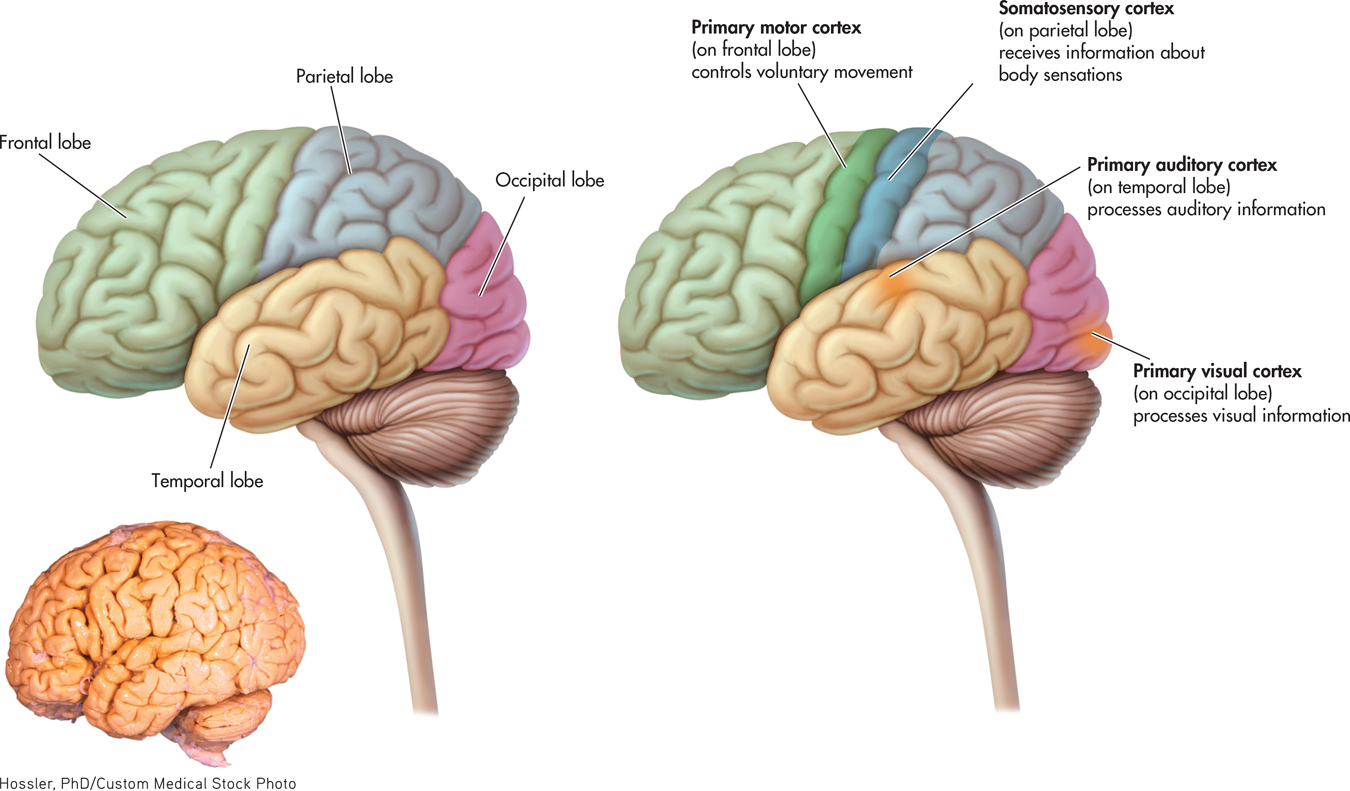

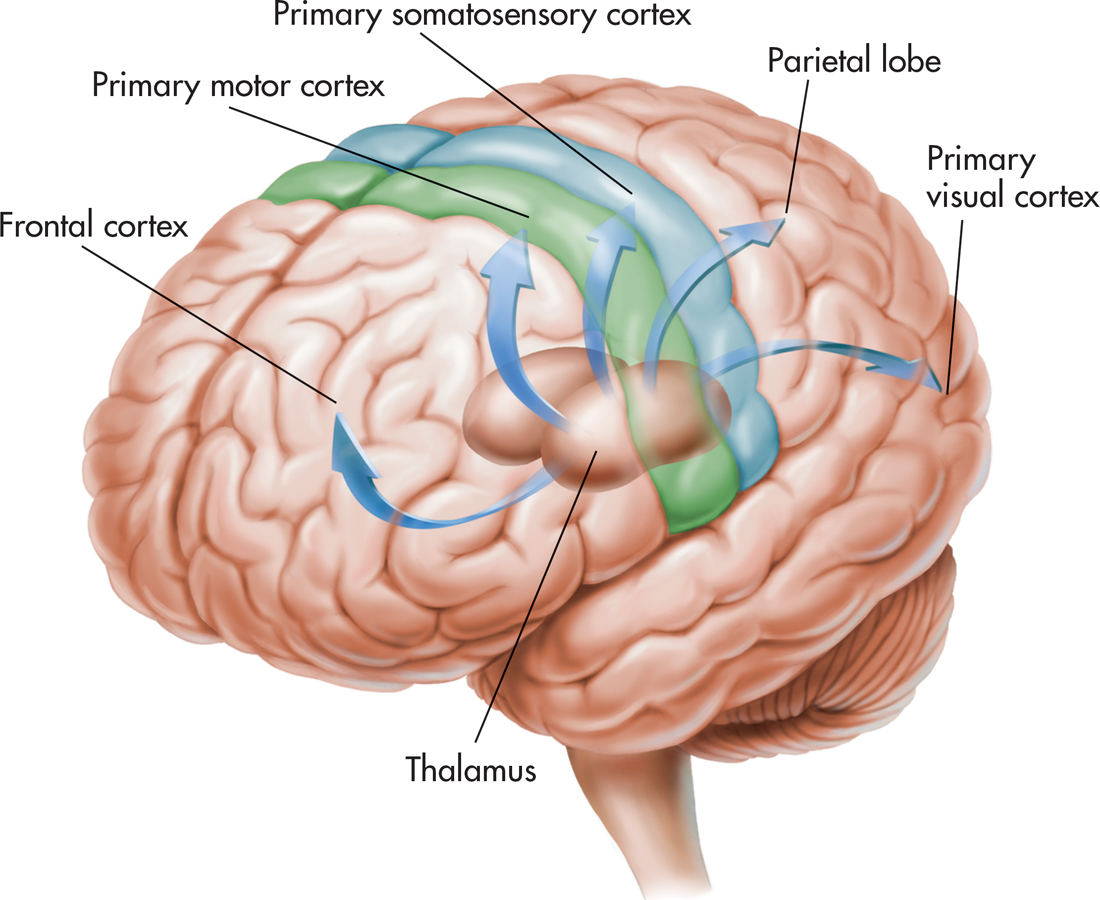

Each cerebral hemisphere can be roughly divided into four regions, or lobes: the temporal, occipital, parietal, and frontal lobes (see FIGURE 2.17). Each lobe is associated with distinct functions. Located near your temples, the temporal lobe contains the primary auditory cortex, which receives auditory information. At the very back of the brain is the occipital lobe. The occipital lobe includes the primary visual cortex, where visual information is received.

temporal lobe

An area on each hemisphere of the cerebral cortex, near the temples, that is the primary receiving area for auditory information.

occipital lobe

(ock-SIP-it-ull) An area at the back of each cerebral hemisphere that is the primary receiving area for visual information.

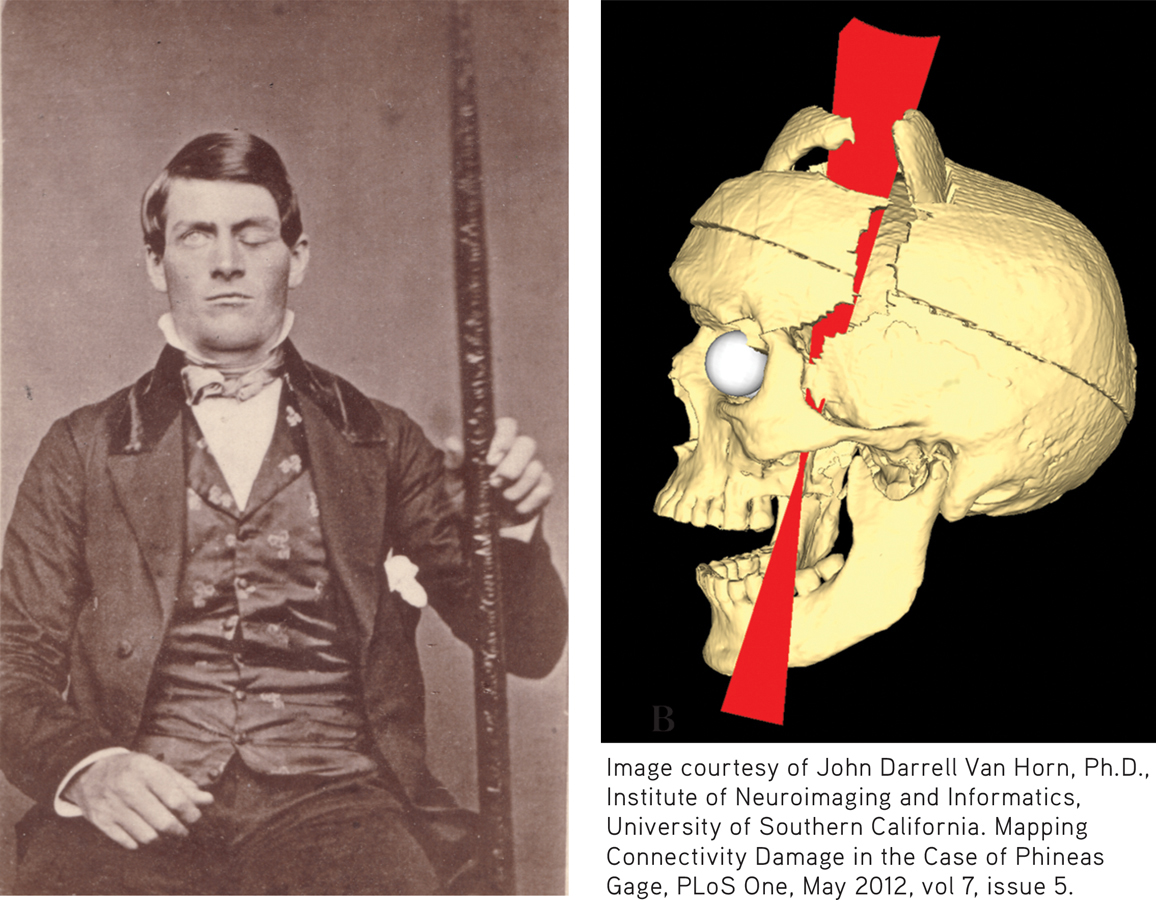

After Gage’s death in 1861, his physician proposed that Gage’s personality changes were caused by damage to his frontal lobes (Harlow, 1868). More than a century later, contemporary neuroscientists studying Gage’s skull confirmed that Gage’s left frontal lobe had been severely damaged (Damasio & others, 1994; Ratiu & Talos, 2004). More recently, models created by neuroscientist John Van Horn and his colleagues (2012) point to probable damage to the white matter connections between Gage’s frontal lobe and other brain regions associated with emotion and memory. This disconnection may have contributed to Gage’s personality changes and lack of emotional control after the accident.

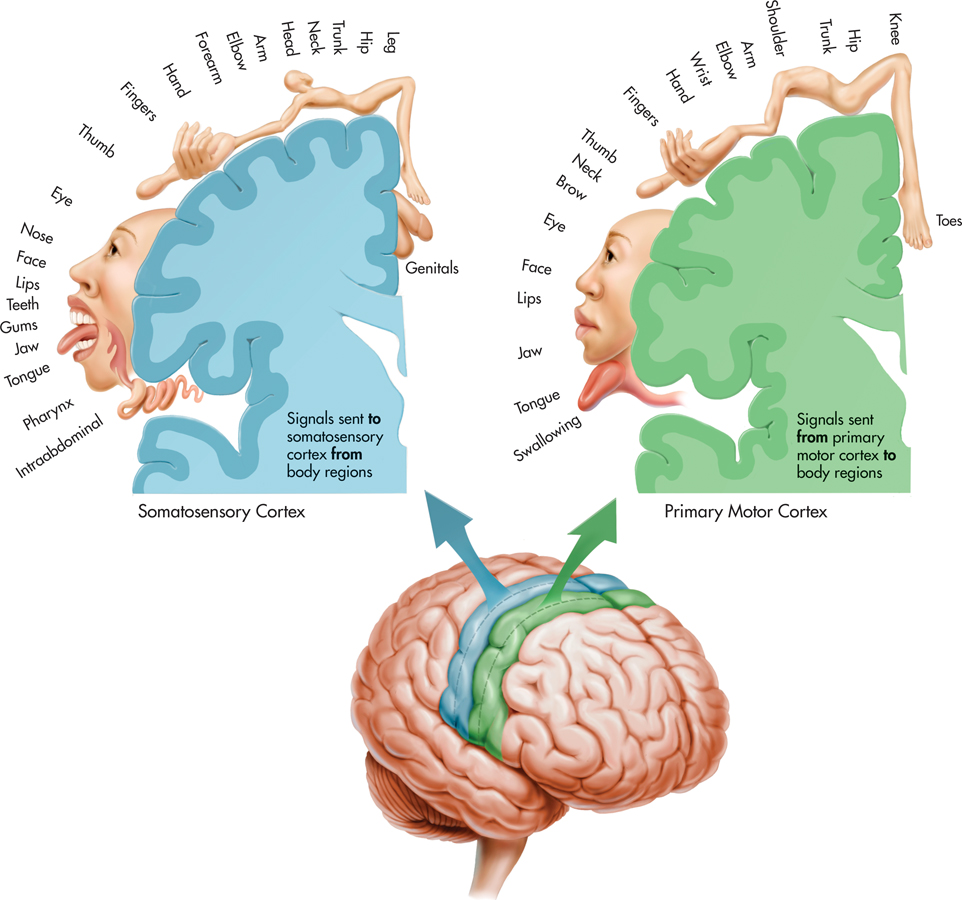

The parietal lobe is involved in processing bodily, or somatosensory, information, including touch, temperature, pressure, and information from receptors in the muscles and joints. A band of tissue on the parietal lobe, called the somatosensory cortex, receives information from touch receptors in different parts of the body.

parietal lobe

(puh-RYE-ut-ull) An area on each hemisphere of the cerebral cortex located above the temporal lobe that processes somatic sensations.

Each part of the body is represented on the somatosensory cortex, but this representation is not equally distributed (see FIGURE 2.18). Instead, body parts are represented in proportion to their sensitivity to somatic sensations. For example, on the left side of FIGURE 2.18, you can see that your hands and face, which are very responsive to touch, have much greater representation on the somatosensory cortex than do the backs of your legs, which are far less sensitive to touch.

The frontal lobe is the largest lobe of the cerebral cortex, and damage to this area of the brain can affect many different functions. The frontal lobe is involved in planning, initiating, and executing voluntary movements. The movements of different body parts are represented in a band of tissue on the frontal lobe called the primary motor cortex. The degree of representation on the primary motor cortex for a particular body part reflects the diversity and precision of its potential movements, as shown on the right side of FIGURE 2.18. Thus, it’s not surprising that almost one-third of the primary motor cortex is devoted to the hands and another third is devoted to facial muscles. The disproportionate representation of these two body areas on the primary motor cortex is reflected in the human capacity to produce an extremely wide range of hand movements and facial expressions.

frontal lobe

The largest lobe of each cerebral hemisphere; processes voluntary muscle movements and is involved in thinking, planning, and emotional control.

The primary sensory and motor areas found on the different lobes represent just a small portion of the cerebral cortex. The remaining bulk of the cerebral cortex consists mostly of association areas, also called the association cortex. These areas are generally thought to be involved in processing and integrating sensory and motor information. For example, the prefrontal association cortex, situated in front of the primary motor cortex, is involved in the planning of voluntary movements. Another association area includes parts of the temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes. This association area is involved in the formation of perceptions and in the integration of perceptions and memories.

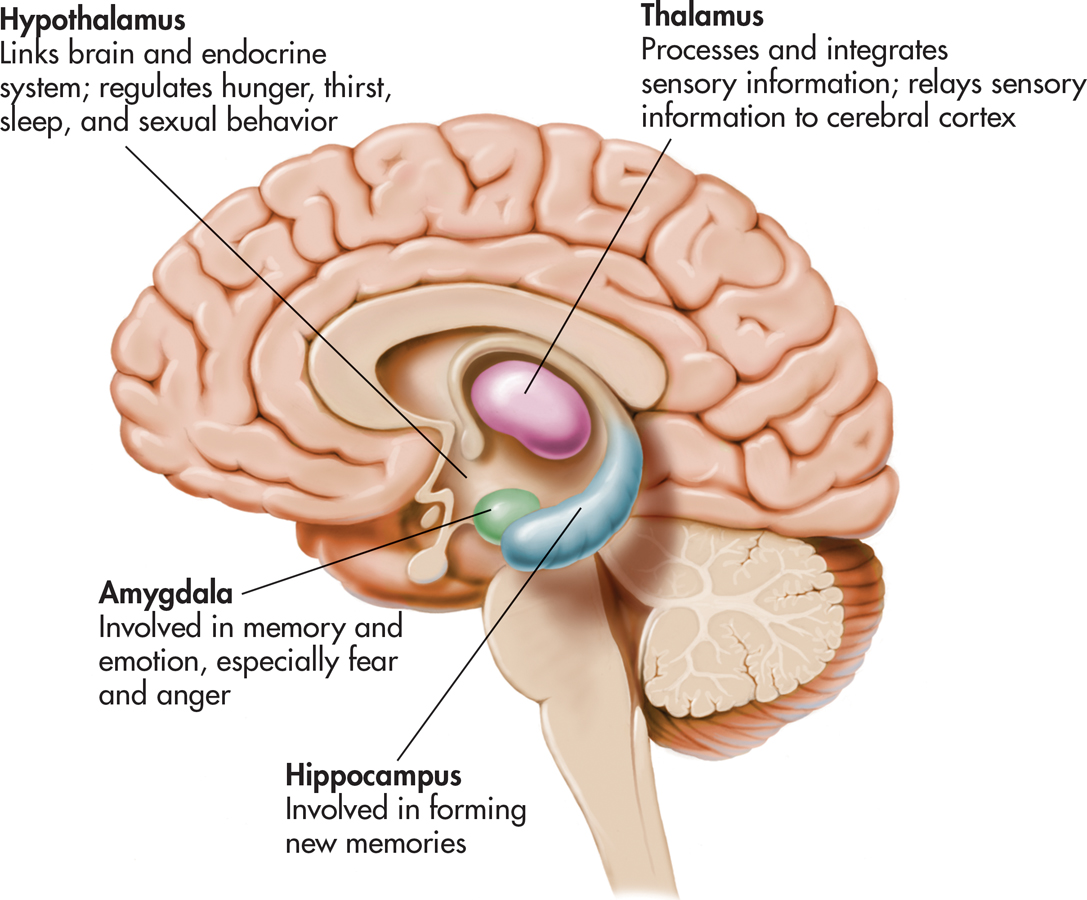

THE LIMBIC SYSTEM

Beneath the cerebral cortex are several other important forebrain structures, which are components of the limbic system. The word limbic means “border,” and as you can see in FIGURE 2.19, the structures that make up the limbic system form a border of sorts around the brainstem. In various combinations, the limbic system structures form complex neural circuits that play critical roles in learning, memory, and emotional control.

limbic system

A group of forebrain structures that form a border around the brainstem and are involved in emotion, motivation, learning, and memory.

Next, we‘ll briefly consider some key limbic system structures and the roles they play in behavior.

The HippocampusThe hippocampus is a large structure embedded in the temporal lobe in each cerebral hemisphere (see FIGURE 2.19). The word hippocampus comes from a Latin word meaning “sea horse.” If you have a vivid imagination, the hippocampus does look a bit like the curved tail of a sea horse. The hippocampus plays an important role in your ability to form new memories of events and information. As noted earlier, neurogenesis takes place in the adult hippocampus. The possible role of new neurons in memory formation is an active area of neuroscience research (see Gould, 2007; Livneh & Mizrahi, 2012). In Chapter 6, we’ll take a closer look at the role of the hippocampus and other brain structures in memory.

hippocampus

A curved forebrain structure that is part of the limbic system and is involved in learning and forming new memories.

The ThalamusThe word thalamus comes from a Greek word meaning “inner chamber.” And indeed, the thalamus is a rounded mass of cell bodies located within each cerebral hemisphere. The thalamus processes and distributes motor information and sensory information (except for smell) going to and from the cerebral cortex. FIGURE 2.20 depicts some of the neural pathways going from the thalamus to the different lobes of the cerebral cortex. However, the thalamus is more than just a sensory relay station. The thalamus is also thought to be involved in regulating levels of awareness, attention, motivation, and emotional aspects of sensations.

thalamus

(THAL-uh-muss) A forebrain structure that processes sensory information for all senses except smell, relaying that information to the cerebral cortex.

The HypothalamusHypo means “beneath” or “below.” As its name implies, the hypothalamus is located below the thalamus. Although it is only about the size of a peanut, the hypothalamus contains more than 40 neural pathways. These neural pathways ascend to other forebrain areas and descend to the midbrain, hindbrain, and spinal cord. The hypothalamus is involved in so many different functions, it is sometimes referred to as “the brain within the brain.”

hypothalamus

(hi-poe-THAL-uh-muss) A peanut-sized forebrain structure that is part of the limbic system and that regulates behaviors related to survival, such as eating, drinking, and sexual activity.

The hypothalamus regulates both divisions of the autonomic nervous system, increasing and decreasing such functions as heart rate and blood pressure. It also helps regulate a variety of behaviors related to survival, such as eating, drinking, frequency of sexual activity, fear, and aggression.

One area of the hypothalamus, called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), plays a key role in regulating daily sleep–

The hypothalamus exerts considerable control over the secretion of endocrine hormones by directly influencing the pituitary gland. The pituitary gland is situated just below the hypothalamus and is attached to it by a short stalk. The hypothalamus produces both neurotransmitters and hormones that directly affect the pituitary gland. As we noted in the section on the endocrine system, the pituitary gland releases hormones that influence the activity of other glands.

The AmygdalaThe amygdala is an almond-shaped clump of neuron cell bodies at the base of the temporal lobe. The amygdala is involved in a variety of emotional responses, including fear, anger, and disgust. Animal studies have shown that electrical stimulation of the amygdala can produce behaviors associated with fear or rage, while destruction of the amygdala reduces or disrupts such behaviors.

amygdala

(uh-MIG-dull-uh) An almond-shaped cluster of neurons in the brain’s temporal lobe, involved in memory and emotional responses, especially fear.

It’s long been known that the amygdala is involved in the detection of threatening stimuli, but neuroscientists have discovered that the amygdala has a broader role. Brain imaging studies have shown that the amygdala responds to many different types of emotional stimuli, appealing as well as upsetting (Cunningham & Brosch, 2012). For example, hungry participants showed increased amygdala activation in response to pictures of food when they were hungry, but not when they were satiated (Mohanty & others, 2008). Thus, some neuroscientists now believe that the amygdala aids in detecting and responding to environmental stimuli that are relevant to an organism’s goals.

The amygdala is also involved in learning and forming memories, especially those with a strong emotional component (Phelps, 2006). In Chapters 6 and 8, we’ll take a closer look at the amygdala’s role in memory and emotion.