4.1 INTRODUCTION:

Consciousness

EXPERIENCING THE “PRIVATE I”

KEY THEME

Consciousness refers to your immediate awareness of mental activity, internal sensations, and external stimuli.

KEY QUESTIONS

What did William James mean by the phrase “stream of consciousness”?

What are the functions of consciousness?

How is attention defined, and how do the limitations of attention affect human thought and behavior?

Its nature is difficult to define precisely. For our purposes, we’ll use a simple definition: Consciousness is your immediate awareness of your internal states—your thoughts, sensations, memories—and the external world around you.

consciousness

Personal awareness of mental activities, internal sensations, and the external environment.

Take a few moments to pay attention to your own experience of consciousness. You’ll notice that the contents of your awareness shift from one moment to the next. Among other activities, your mental experience might include focused attention on this textbook; awareness of internal sensations, such as hunger or a throbbing headache; or planning and active problem-solving, such as mentally rehearsing an upcoming meeting with your adviser.

Even though your conscious experience is constantly changing, you don’t experience your personal consciousness as disjointed. Rather, the subjective experience of consciousness has a sense of continuity. This characteristic of consciousness led the influential American psychologist William James (1892) to describe consciousness as a “stream” or “river.” Despite the changing focus of our awareness, our experience of consciousness as an unbroken “stream” helps provide us with a sense of personal identity that has continuity from one day to the next.

Consciousness, then, does not appear to itself chopped up in bits…. It is nothing jointed; it flows. A “river” or a “stream” are the metaphors by which it is most naturally described. In talking of it hereafter, let us call it the stream of thought, or consciousness, of subjective life.

—William James (1892)

Consciousness allows us to integrate past, present, and future behavior, guide future actions, and maintain a stable sense of self (Baumeister & others, 2010, 2011). And, it gives us the ability to plan and execute long-term, complex goals and communicate with others.

Our definition of consciousness refers to waking awareness. However, psychologists also study other types of conscious experience, which we’ll consider later in the chapter. But first, we’ll take a closer look at the nature of awareness.

Attention

THE MIND’S SPOTLIGHT

Lost in your thoughts, you don’t notice when your instructor calls on you in class. “Pay attention!” your professor says patiently.

But what is attention? In reality, you are always “paying attention” to something—just not always the stimuli that you’re supposed to be paying attention to. For example, when your mind “wanders,” you are focusing on your internal environment—your daydreams or thoughts—rather than your external environment (Smilek & others, 2010).

Like consciousness, attention is one of the oldest topics in psychology (Raz, 2009). And, like consciousness, attention is difficult to define precisely.

For our purposes, we’ll define attention as the capacity to selectively focus senses and awareness on particular stimuli or aspects of the environment (Chun & others, 2011; Posner & Rothbart, 2007). Most of the time, we are able to deliberately control our attentional processes, which helps us regulate our thoughts and feelings. For example, we may deliberately turn our attention to a pleasant thought or memory when troubled by a painful memory (Baumeister & others, 2010, 2011).

attention

The capacity to selectively focus awareness on particular stimuli in your external environment or on your internal thoughts or sensations.

Everyone knows what attention is. It is the taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought…. It implies withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others.

—William James (1890)

Psychologists have identified a number of characteristics of attention, some of which have important implications for our daily life. These are:

Attention has a limited capacity.

At any given moment we are faced with more information than we can effectively process. We cannot pay attention to all of the sights, sounds, or other sensations in our external environments. Similarly, the range of potential thoughts, memories, or fantasies available to us at any given time is overwhelming. Thus, we focus our attention on the information that is most relevant to our immediate or long-term goals (Chun & others, 2011; Lachter & others, 2004).

Attention is selective.

Attention is often compared to a spotlight that we shine on particular external stimuli or internal thoughts. Like a spotlight, we focus on certain areas of our experience while ignoring others (Dijksterhuis & Aarts, 2010).

A classic example of the selective nature of attention is the cocktail party effect (Hill & Miller, 2010). If you’re at a crowded, noisy party, you’re literally engulfed in a sea of auditory stimuli. But, you are able to attend to one stream of speech while ignoring others that compete for your attention (Koch & others, 2011; Xiang & others, 2010).

Did You See That Clown? Do you think you would notice if a unicycling clown crossed your path? Probably—unless you were using a cell phone! Fully three-quarters of students who were talking on cell phones did not see this clown as they walked across a busy campus square—an example of inattentional blindness (Hyman & others, 2010).Photo courtesy Ira Hyman. © John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

Did You See That Clown? Do you think you would notice if a unicycling clown crossed your path? Probably—unless you were using a cell phone! Fully three-quarters of students who were talking on cell phones did not see this clown as they walked across a busy campus square—an example of inattentional blindness (Hyman & others, 2010).Photo courtesy Ira Hyman. © John Wiley & Sons, LtdAlthough you can monitor multiple streams of information, you can only truly pay attention to one stream of speech at a time. So, at the same party, you are somewhat aware of information that is going on in the background, even though you’re not actively paying attention to it (Raz, 2009). For example, if you hear your name mentioned by someone in a different conversational group, you will probably shift your attention to the other conversation and strain your ears to hear what is being said about you. Meanwhile, your best friend has been talking to you, and you haven’t heard a word he’s said. Sound familiar?

Attention can be “blind.”

Given the limited, selective nature of attention, you shouldn’t be surprised to learn that we often completely miss what seem to be obvious stimuli in our field of vision or hearing. For example, magicians exploit the limited, selective nature of attention with a strategy called misdirection (Lamont & others, 2010). They deliberately draw the audience’s attention away from the “method,” or secret action, and towards the “effect,” which refers to what the magician wants the audience to perceive (Macknik & others, 2008; Raz, 2009). To experience a bit of magic firsthand, direct your attention to FIGURE 4.1.

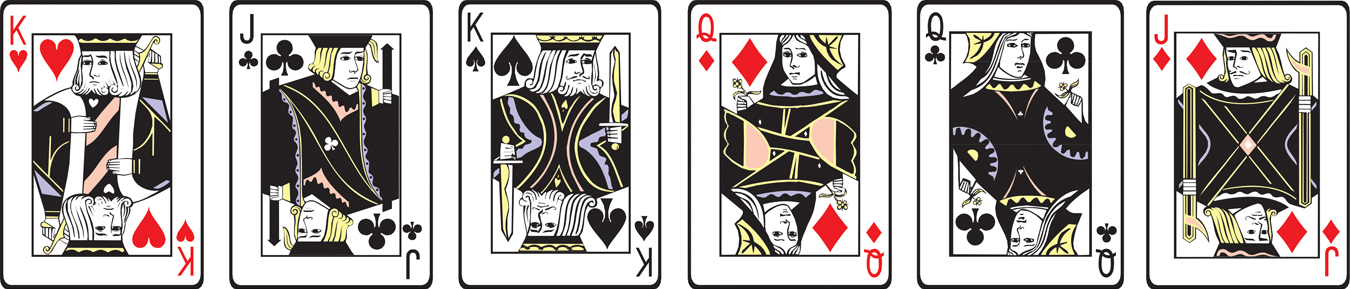

Figure 4.1: FIGURE 4.1(a) Can We Read Your Mind? We’d like you to participate in a mind-reading experiment. Please follow all directions as carefully as you can. First, pick one of the six cards above and remember it.

Figure 4.1: FIGURE 4.1(a) Can We Read Your Mind? We’d like you to participate in a mind-reading experiment. Please follow all directions as carefully as you can. First, pick one of the six cards above and remember it. Say its name aloud several times so you won’t forget it. Once you’re sure you’ll remember it, circle one of the eyes in the row to the right. Then turn to page 138.Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2008 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved.

Say its name aloud several times so you won’t forget it. Once you’re sure you’ll remember it, circle one of the eyes in the row to the right. Then turn to page 138.Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2008 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved.!launch!

Think you’re good at paying attention? Try Video Activity: Attention.Worth Publishers

Think you’re good at paying attention? Try Video Activity: Attention.Worth PublishersMagicians also exploit a basic human tendency known as inattentional blindness, which occurs when we simply don’t notice some significant object or event that is in our clear field of vision (Mack & Rock, 2000). Because we have a limited capacity for attention, the more attention we devote to one task, the less we have for another. Thus, when we are engaged in one task that demands a great deal of our attention, we may fail to notice an event or object, especially if it is unexpected or unusual.

For example, if a clown on a unicycle crossed your path while you were walking across campus, do you think you would notice? Psychologist Ira Hyman enlisted a student to dress up as a clown and slowly unicycle across a busy campus square (Hyman & others, 2010). Researchers later stopped people whose paths had crossed with the unicycling clown and asked them whether they had seen him. Most of the people who were walking alone, in pairs, or who were listening to iPods did notice the clown. However, only one-quarter of those talking on cell phones noticed the clown.

We can also experience inattentional deafness (Macdonald & Lavie, 2011). Most of us have been so engrossed in a book or video that we failed to hear a roommate’s question.

Finally, change blindness is also relatively common. Change blindness refers to not noticing when something changes, such as when a friend gets a haircut or shaves his beard (Rosielle & Scaggs, 2008). Were you fooled by the magic trick in FIGURE 4.1? If so, you can blame change blindness.

The Perils of Multi-Tasking

Multi-tasking refers to paying attention to two or more sources of stimuli at once—such as doing homework while watching television, or talking on the phone while cooking dinner. In essence, multi-tasking involves the division of attention. When attention is divided among different tasks, each task receives less attention than it would normally (Borst & others, 2010; Lavie, 2010). Some people are better at handling multiple tasks than others (Seegmiller & others, 2011). However, people generally underestimate the costs of multitasking. When you attempt to do two things at once—such as talk on the phone while studying—your performance on both tasks is impaired (Finley & others, 2014).

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that multi-tasking is an efficient way to get things done?

In general, tasks that are very different are less likely to interfere with each other. There is evidence that visual and auditory tasks draw on independent, different attention resources—at least for simple, well-rehearsed tasks. For example, listening to the radio (an auditory task) interferes less with driving (a visual task) than would a second visual task (Borst & others, 2010). However, this is not the case when one of the tasks requires a great deal of concentration. Absorption in a visual task can produce inattentional deafness, and absorption in an auditory task can produce inattentional blindness (Macdonald & Lavie, 2011).

Think Like a SCIENTIST

Are you good at working on several tasks at once? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about Multi-Tasking.

The perils of divided attention are especially obvious when people use cell phones. As demonstrated by the unicycling clown study, using a cell phone seems to absorb a great deal of attentional resources. Partly because cell phone conversations can be so absorbing, they are especially likely to produce inattentional blindness (Chabris & Simons, 2010). One study found that driving was more impaired when drivers were talking on a cell phone than when the same drivers were legally drunk (Strayer & others, 2006). And, it turns out, using a headset or Bluetooth device while driving does not improve safety. It’s the attention devoted to the conversation that is dangerously distracting to drivers (see Baumeister & others, 2011; Drews & others, 2008). In fact, the National Safety Council (2014) found that cell phone use was involved in more than a quarter of motor vehicle crashes in 2012 – that’s 1.5 million accidents!

Distractions are just one factor that affects the quality of awareness. We’ll begin our exploration of variations in consciousness by looking at the biological rhythms that help determine the nature and quality of our daily conscious experience.