6.2 Retrieval

GETTING INFORMATION FROM LONG-TERM MEMORY

KEY THEME

Retrieval refers to the process of accessing and retrieving stored information in long-term memory.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are retrieval cues and how do they work?

What do tip-of-the-tongue experiences tell us about the nature of memory?

How is retrieval tested, and what is the serial position effect?

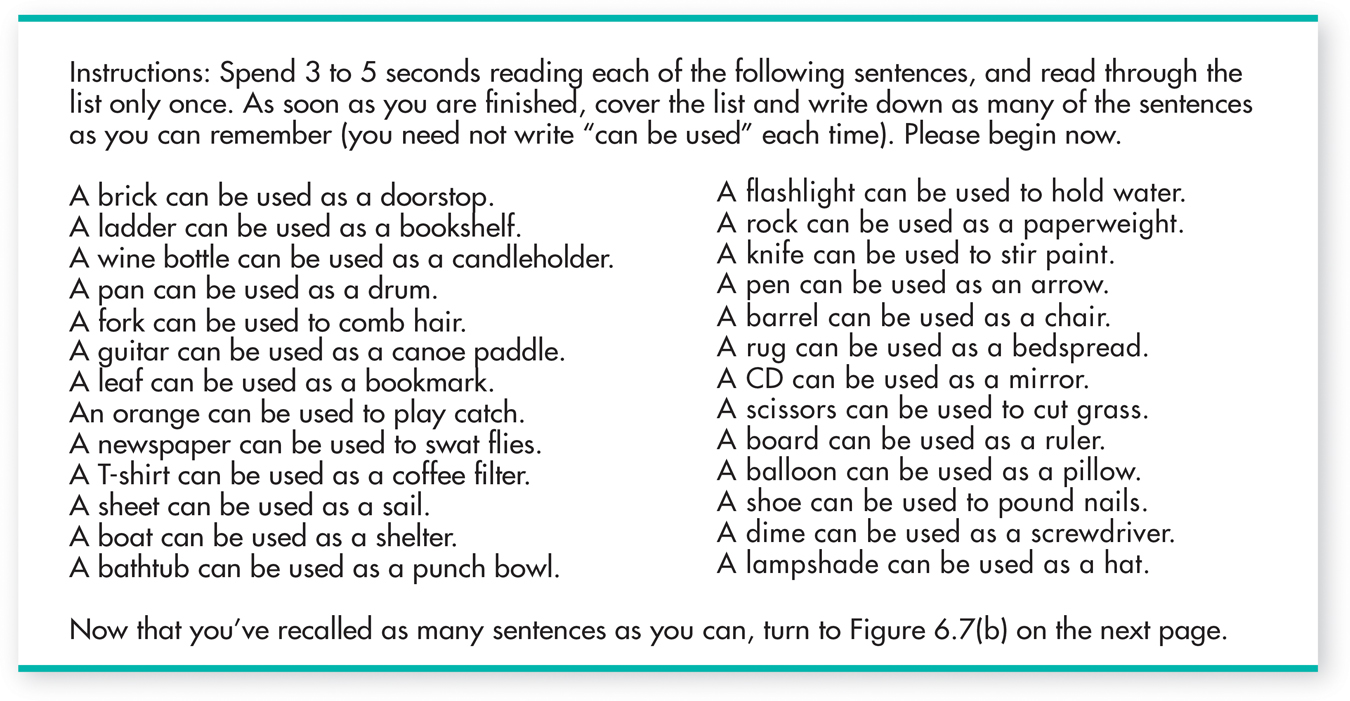

So far, we’ve discussed some of the important factors that affect encoding and storing information in memory. In this section, we will consider factors that influence the retrieval process. Before you read any further, try the demonstration in FIGURE 6.7a. After completing part (a), try part (b). We’ll refer to this demonstration throughout this section, so please take a shot at it. After you’ve completed both parts of the demonstration, continue reading.

The Importance of Retrieval Cues

Retrieval refers to the process of accessing, or retrieving, stored information. There’s a vast difference between what is stored in our long-term memory and what we can actually access. In many instances, our ability to retrieve stored memory hinges on having an appropriate retrieval cue. A retrieval cue is a clue, prompt, or hint that can help trigger recall of a stored memory. If your performance on the demonstration experiment in FIGURE 6.7a was like ours, the importance of retrieval cues should have been vividly illustrated.

retrieval

The process of recovering information stored in memory so that we are consciously aware of it.

retrieval cue

A clue, prompt, or hint that helps trigger recall of a given piece of information stored in long-term memory.

Let’s compare results. How did you do on the first part of the demonstration, in FIGURE 6.7a? After generating a number of answers, you probably reached a point at which you were unable to remember any more pairs. At that point, you experienced retrieval cue failure, which refers to the inability to recall long-term memories because of inadequate or missing retrieval cues.

retrieval cue failure

The inability to recall long-term memories because of inadequate or missing retrieval cues.

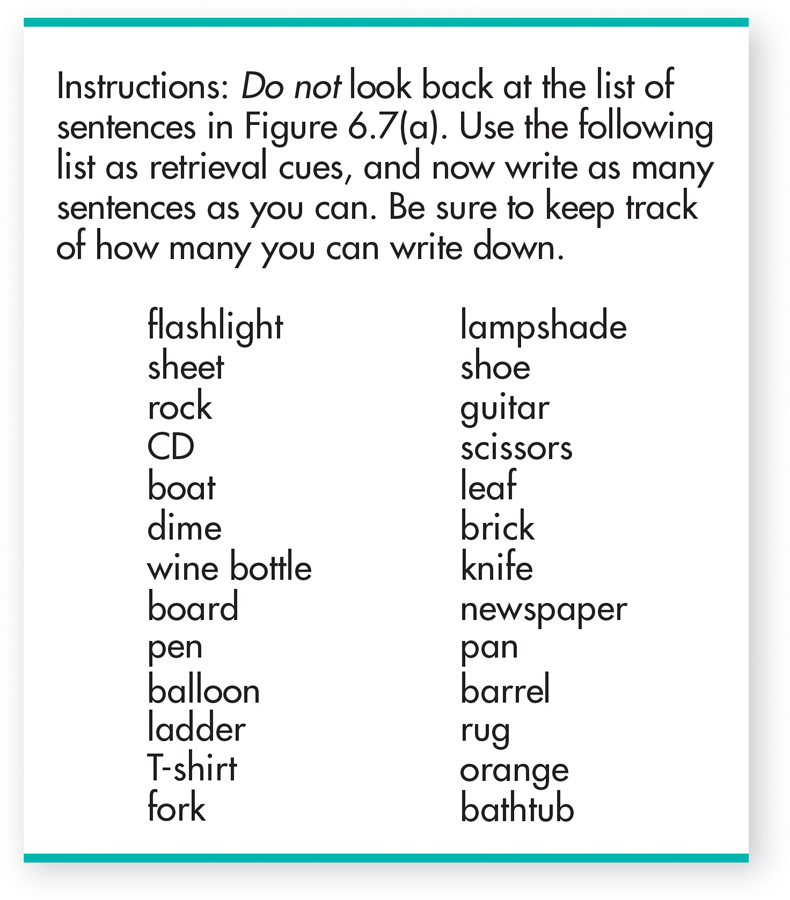

You should have done much better on the demonstration in FIGURE 6.7b. Why the improvement? In part (b) you were presented with retrieval cues that helped you access your stored memories.

This exercise demonstrates the difference between information that is stored in long-term memory versus the information that you can access. Many of the items on the list that you could not recall in part (a) were not forgotten. They were simply inaccessible—until you had a retrieval cue to help jog your memory. This exercise illustrates that many memories only appear to be forgotten. With the right retrieval cue, you can often access stored information that seemed to be completely unavailable.

COMMON RETRIEVAL GLITCHESTHE TIP-OF-THE-TONGUE EXPERIENCE

Quick—what is the name of the actor who stars in the Ironman film series? How about the four “houses” at Hogwarts in the Harry Potter books? If popular culture isn’t your thing, how about this question: Who wrote the words to “The Star-Spangled Banner”?

Did any of these questions leave you feeling as if you knew the answer but just couldn’t quite recall it? If so, you experienced a common, and frustrating, form of retrieval failure, called the tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) experience. The TOT experience refers to the inability to get at a bit of information that you’re absolutely certain is stored in your memory. Subjectively, it feels as though the information is very close, but just out of reach—or on the tip of your tongue (Schwartz, 2002, 2011).

tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) experience

A memory phenomenon that involves the sensation of knowing that specific information is stored in long-term memory, but being temporarily unable to retrieve it.

TOT experiences appear to be universal, and the “tongue” metaphor is used to describe the experience in many cultures (Brennen & others, 2007; Schwartz, 1999, 2002). On average, people have about one TOT experience per week. Although people of all ages experience such word-finding memory glitches, TOT experiences tend to be more common among older adults than younger adults (Farrell & Abrams, 2011).

When experiencing this sort of retrieval failure, people can almost always dredge up partial responses or related bits of information from their memory. About half the time, people can accurately identify the first letter of the target word and the number of syllables in it. They can also often produce words with similar meanings or sounds. While momentarily frustrating, about 90 percent of TOT experiences are eventually resolved, often within a few minutes.

Tip-of-the-tongue experiences illustrate that retrieving information is not an all-or-nothing process. Often, we remember bits and pieces of what we want to remember. In many instances, information is stored in memory but is not accessible without the right retrieval cues. TOT experiences also emphasize that information stored in memory is organized and connected in relatively logical ways. As you mentally struggle to retrieve the blocked information, logically connected bits of information are frequently triggered. In many instances, these related tidbits of information act as additional retrieval cues, helping you access the desired memory.

TESTING RETRIEVALRECALL, CUED RECALL, AND RECOGNITION

The first part of the demonstration in FIGURE 6.7a illustrated the use of recall as a strategy to measure memory. Recall, also called free recall, involves producing information using no retrieval cues. This is the memory measure that’s used on essay tests. Other than the essay questions themselves, an essay test provides no additional retrieval cues to help jog your memory.

recall

A test of long-term memory that involves retrieving information without the aid of retrieval cues; also called free recall.

The second part of the demonstration used a different memory measurement, called cued recall. Cued recall involves remembering an item of information in response to a retrieval cue. Fill-in-the-blank and matching questions are examples of cued-recall tests.

cued recall

A test of long-term memory that involves remembering an item of information in response to a retrieval cue.

A third memory measurement is recognition, which involves identifying the correct information from several possible choices. Multiple-choice tests involve recognition as a measure of long-term memory. The multiple-choice question provides you with one correct answer and several wrong answers. If you have stored the information in your long-term memory, you should be able to recognize the correct answer.

recognition

A test of long-term memory that involves identifying correct information out of several possible choices.

Cued-recall and recognition tests are clearly to the student’s advantage. Because these kinds of tests provide retrieval cues, the likelihood that you will be able to access stored information is increased.

THE SERIAL POSITION EFFECT

Notice that the first part of the demonstration in FIGURE 6.7a did not ask you to recall the sentences in any particular order. Instead, the demonstration tested free recall—you could recall the items in any order. Take another look at your answers to FIGURE 6.7a. Do you notice any sort of pattern to the items that you did recall?

Most people are least likely to recall items from the middle of the list. This pattern of responses is called the serial position effect, which refers to the tendency to retrieve information more easily from the beginning and the end of a list rather than from the middle. There are two parts to the serial position effect. The tendency to recall the first items in a list is called the primacy effect, and the tendency to recall the final items in a list is called the recency effect.

serial position effect

The tendency to remember items at the beginning and end of a list better than items in the middle.

The primacy effect is especially prominent when you have to engage in serial recall, that is, when you need to remember a list of items in their original order. Remembering speeches, telephone numbers, and directions are a few examples of serial recall.

The Encoding Specificity Principle

KEY THEME

According to the encoding specificity principle, re-creating the original learning conditions makes retrieval easier.

KEY QUESTIONS

How can context and mood affect retrieval?

What role does distinctiveness play in retrieval, and how accurate are flashbulb memories?

One of the best ways to increase access to information in memory is to re-create the original learning conditions. This simple idea is formally called the encoding specificity principle (Tulving, 1983). As a general rule, the more closely retrieval cues match the original learning conditions, the more likely it is that retrieval will occur.

encoding specificity principle

The principle that when the conditions of information retrieval are similar to the conditions of information encoding, retrieval is more likely to be successful.

For example, have you ever had trouble remembering some bit of information during a test but immediately recalled it as you entered the library where you normally study? When you intentionally try to remember some bit of information, such as the definition of a term, you often encode much more into memory than just that isolated bit of information. As you study in the library, at some level you’re aware of all kinds of environmental cues. These cues might include the sights, sounds, and aromas within that particular situation. The environmental cues in a particular context can become encoded as part of the unique memories you form while in that context. These same environmental cues can act as retrieval cues to help you access the memories formed in that context.

This particular form of encoding specificity is called the context effect. The context effect is the tendency to remember information more easily when the retrieval occurs in the same setting in which you originally learned the information. Thus, the environmental cues in the library where you normally study act as additional retrieval cues that help jog your memory. Of course, it’s too late to help your test score, but the memory was there.

context effect

The tendency to recover information more easily when the retrieval occurs in the same setting as the original learning of the information.

A different form of encoding specificity is called mood congruence—the idea that a given mood tends to evoke memories that are consistent with that mood. In other words, a specific emotional state can act as a retrieval cue that evokes memories of events involving the same emotion. So, when you’re in a positive mood, you’re more likely to recall positive memories. When you’re feeling blue, you’re more likely to recall negative or unpleasant memories.

mood congruence

An encoding specificity phenomenon in which a given mood tends to evoke memories that are consistent with that mood.

Flashbulb Memories

VIVID EVENTS, ACCURATE MEMORIES?

If you rummage around your own memories, you’ll quickly discover that highly unusual, surprising, or even bizarre experiences are easier to retrieve from memory than are routine events (Geraci & Manzano, 2010). Such memories are said to be characterized by a high degree of distinctiveness. That is, the encoded information represents a unique, different, or unusual memory.

Various events can create vivid, distinctive, and long-lasting memories that are sometimes referred to as flashbulb memories (Brown & Kulik, 1982). Just as a camera flash captures the specific details of a scene, a flashbulb memory is thought to involve the recall of very specific details or images surrounding a significant, rare, or vivid event.

flashbulb memory

The recall of very specific images or details surrounding a vivid, rare, or significant personal event; details may or may not be accurate.

Do flashbulb memories literally capture specific details, like the details of a photograph, that are unaffected by the passage of time? Emotionally charged national events have provided a unique opportunity to study flashbulb memories. On September 12, 2001, psychologists Jennifer Talarico and David Rubin (2003, 2007) had Duke University students complete questionnaires about the terrorist attacks on the United States that had occurred the previous day. The students were asked such questions as: “Where were you when you first heard the news?” “Were there others present, and if so, who?” “What were you doing immediately before you first heard the news?” For comparison, the students also described some ordinary, everyday event that had occurred in their lives at about the same time, such as attending a sporting event or party.

Flashbulb memories are not immune to forgetting, nor are they uncommonly consistent over time. Instead, exaggerated belief in memory’s accuracy at long delays is what may have led to the conviction that flashbulb memories are more accurate than everyday memories.

—Jennifer Talarico and David Rubin (2003)

Students were randomly assigned to a follow-up session either 1 week, 6 weeks, or 32 weeks later. At the follow-up sessions, they were asked to describe their memories of the ordinary event as well as their memory of the 9/11 attacks. They were also asked to evaluate the accuracy and vividness of their memories. Then, the researchers compared these accounts to their reports on September 12, 2001. All of the students were tested again in late August 2002—almost a full year after the attacks.

How did the flashbulb memories compare to the ordinary memories? Were the flashbulb memories more likely to be preserved unchanged over time? Not at all. Both the flashbulb and everyday memories gradually decayed over time: The number of consistent details decreased and the number of inconsistent details increased. However, when the students rated the memory’s vividness, their ability to recall the memory, and their belief in the memory’s accuracy, only the ratings for the ordinary memory declined. In other words, despite having the same level of inconsistencies as the ordinary memories, the students perceived their flashbulb memories of 9/11 as being vivid and accurate.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that “flashbulb memories,” the vivid memories you form after an important, dramatic event, are no more accurate than other memories?

Although flashbulb memories can seem incredibly vivid, they appear to function just as normal, everyday memories do (Talarico & Rubin, 2009). We remember some details, forget some details, and think we remember some details. What does seem to distinguish flashbulb memories from ordinary memories is the high degree of confidence the person has in the accuracy of these memories. But clearly, confidence in a memory is no guarantee of accuracy. We’ll come back to that important point shortly.

Test your understanding of Memory with

.

.