6.4 Imperfect Memories

ERRORS, DISTORTIONS, AND FALSE MEMORIES

KEY THEME

Memories can be easily distorted so that they contain inaccuracies. Confidence in a memory is no guarantee that the memory is accurate.

KEY QUESTIONS

What is the misinformation effect?

What is source confusion, and how can it distort memories?

What are schemas and scripts, and how can they contribute to memory distortions?

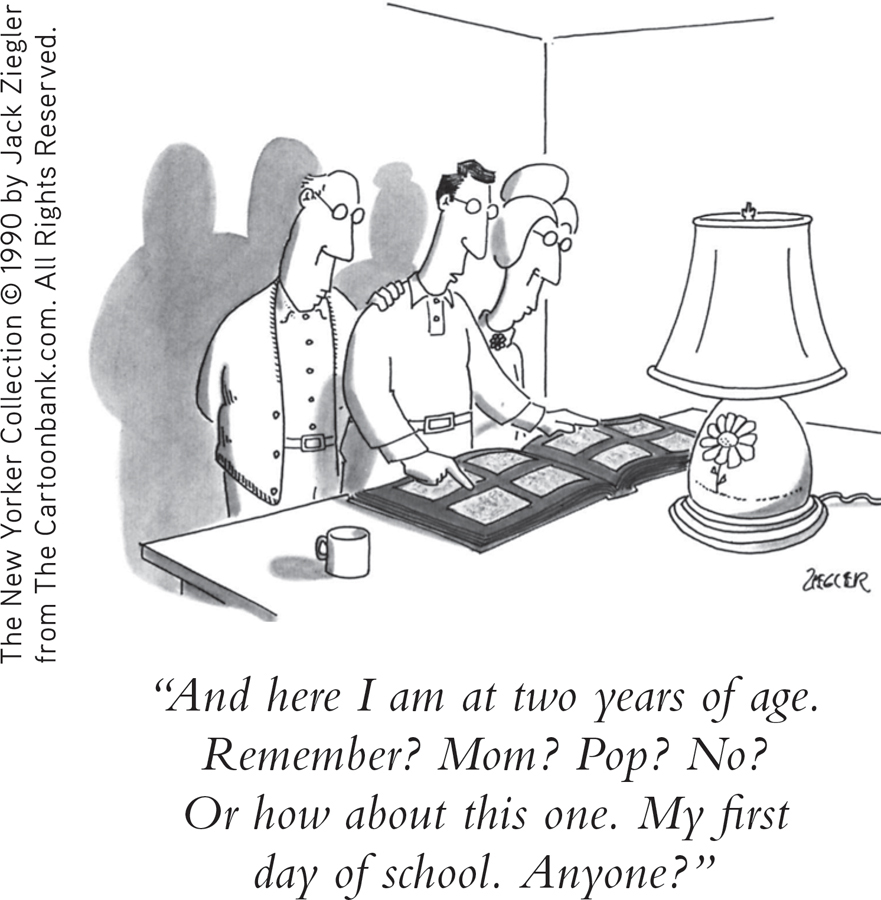

Although people usually remember the general gist of what they experience, the fallibility of human memory is disturbing. Human memory does not function like a camera or digital recorder that captures a perfect copy of visual or auditory information (Schacter & Loftus, 2013). Instead, memory details can change over time. Without your awareness, details can be added, subtracted, exaggerated, or downplayed. In fact, each of us has the potential to confidently and vividly remember the details of some event—and be completely wrong. Confidence in a memory is no guarantee that the memory is accurate.

How do errors and distortions creep into memories? A new memory is not simply recorded, but actively constructed. To form a new memory, you actively organize and encode different types of information—visual, auditory, tactile, and so on. When you later attempt to retrieve those details, you actively reconstruct, or rebuild, the details of the memory (Bartlett, 1932; Stark & others, 2010). In the process of actively constructing or reconstructing a memory, various factors can contribute to errors and distortions in what you remember—or, more accurately, what you think you remember.

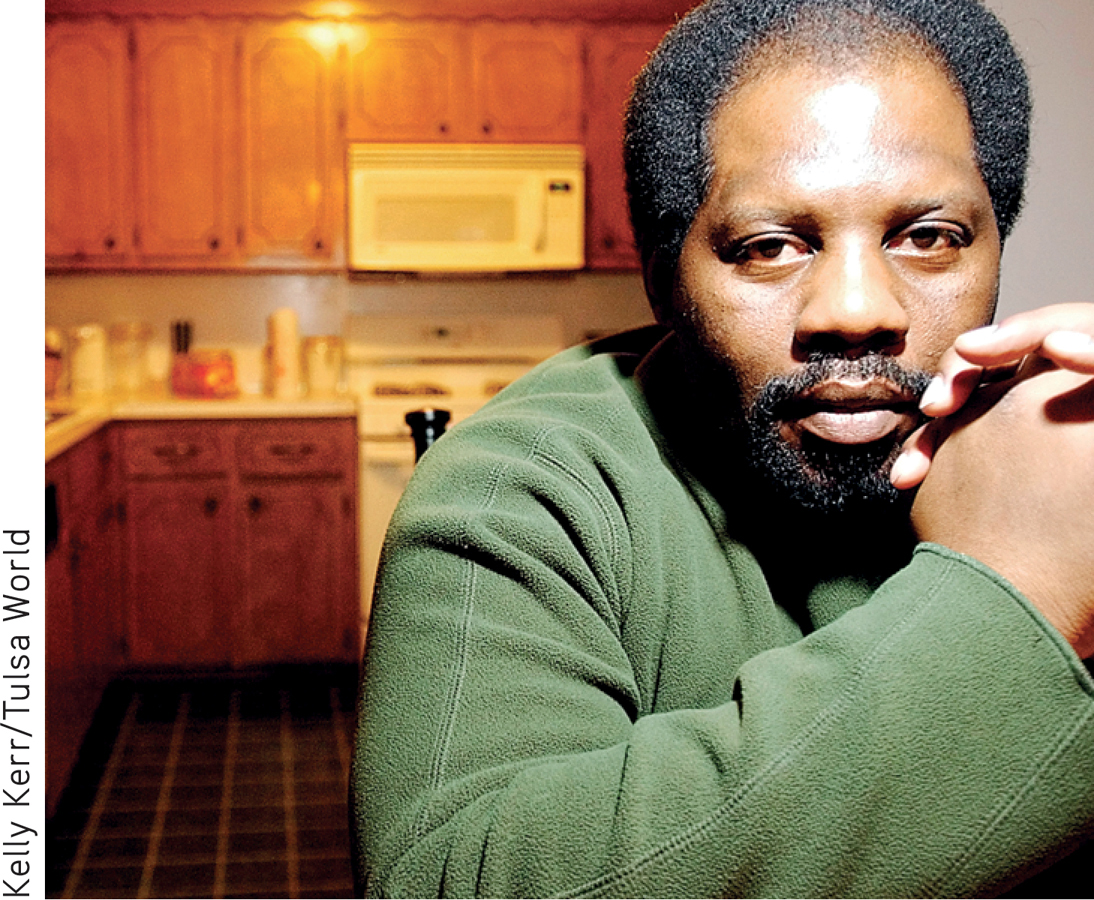

At the forefront of research on memory distortions is Elizabeth Loftus, whose story we told in the Prologue. Loftus is one of the most widely recognized authorities on eyewitness memory and the different ways it can go awry. She has not only conducted extensive research on this topic, but also testified as an expert witness in many high-profile cases (see Loftus, 2007, 2011).

Psychological studies have shown that it is virtually impossible to tell the difference between a real memory and one that is a product of imagination or some other process. Our job as researchers in this area is to understand how it is that pieces of experience are combined to produce what we experience as “memory.”

—Elizabeth Loftus (2002)

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that memory is like a video recorder—it preserves a perfect record of your experience?

THE MISINFORMATION EFFECTTHE INFLUENCE OF POST-EVENT INFORMATION ON MISREMEMBERING

Let’s start by considering a Loftus study that has become a classic piece of research. Loftus and co-researcher John C. Palmer (1974) had subjects watch a film of an automobile accident, write a description of what they saw, and then answer a series of questions. There was one critical question in the series: “About how fast were the cars going when they contacted each other?” Different subjects were given different versions of that question. For some subjects, the word contacted was replaced with hit. Other subjects were given the words bumped, collided, or smashed.

Depending on the specific word used in the question, subjects gave very different speed estimates. As shown in TABLE 6.2, the subjects who gave the highest speed estimates got smashed (so to speak). Clearly, how a question is worded can influence what is remembered.

Estimated Speeds

| Word Used In Question | Average Speed Estimate |

|---|---|

| smashed | 41 m.p.h. |

| collided | 39 m.p.h. |

| bumped | 38 m.p.h. |

| hit | 34 m.p.h. |

| contacted | 32 m.p.h. |

| Source: Research from Loftus & Palmer (1974). | |

A week after seeing the film, the subjects were asked another series of questions. This time, the critical question was “Did you see any broken glass?” Although no broken glass was shown in the film, the majority of the subjects whose question had used the word smashed a week earlier said “yes.” Notice what happened: Following the initial memory (the film of the automobile accident), new information (the word smashed) distorted the reconstruction of the memory (remembering broken glass that wasn’t really there).

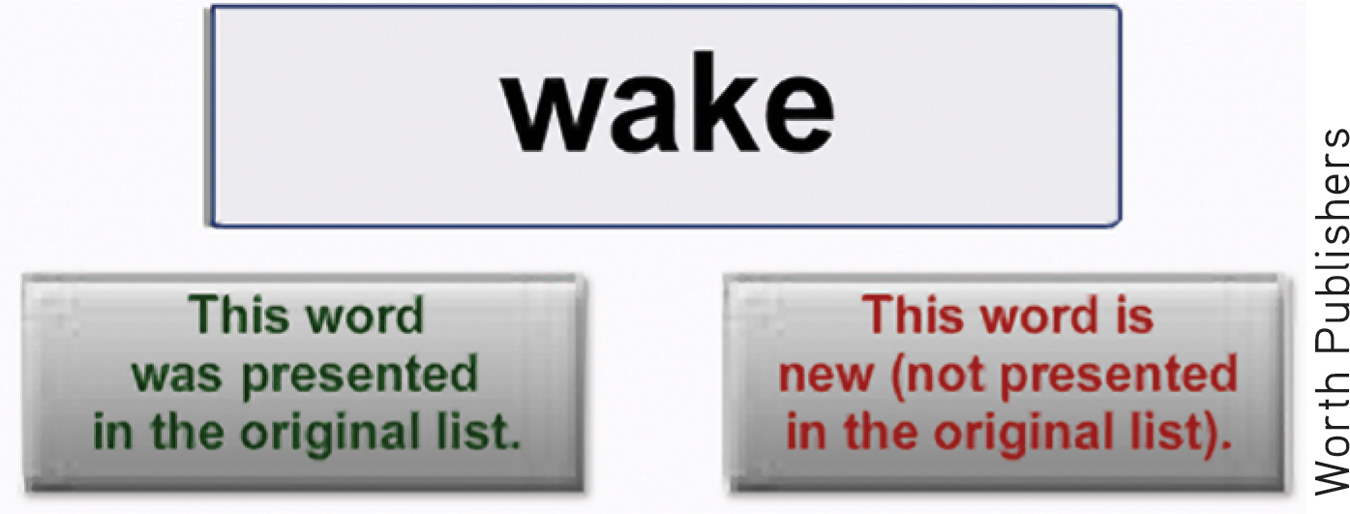

The use of suggestive questions is but one example of how the information a person gets after an event can change what the person later remembers about the event. Literally hundreds of studies have demonstrated the different ways that the misinformation effect can be produced (Loftus, 1996, 2005). Basically, the research procedure involves three steps. First, participants are exposed to a simulated event, such as an automobile accident or a crime. Next, after a delay, half of the participants receive misinformation, while the other half receive no misinformation. In the final step, all of the participants try to remember the details of the original event.

misinformation effect

A memory-distortion phenomenon in which your existing memories can be altered if you are exposed to misleading information.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that eyewitness testimony is the most reliable form of courtroom evidence?

In study after study, Loftus as well as other researchers have confirmed that post-event exposure to misinformation can distort the recollection of the original event by eyewitnesses (see Davis & Loftus, 2007; Frenda & others, 2011). People have recalled stop signs as yield signs, normal headlights as broken, barns along empty country roads, a blue vehicle as being white, and Minnie Mouse when they really saw Mickey Mouse! Whether it is in the form of suggestive questions, misinformation, or other exposure to conflicting details, such post-event experiences can distort eyewitness memories (Brewer & Wells, 2011).

SOURCE CONFUSIONMISREMEMBERING THE SOURCE OF A MEMORY

Have you ever confidently remembered hearing something on television only to discover that it was really a friend who told you the information? Or mistakenly remembered doing something that you actually only imagined doing? Or confidently remembered that an event happened at one time and place only to learn later that it really happened at a different time and place?

If so, you can blame your faulty memories on a phenomenon called source confusion. Source confusion arises when the true source of the memory is forgotten or when a memory is attributed to the wrong source (Johnson & others, 2012; Lindsay, 2008). The notion of source confusion can help explain the misinformation effect: False details provided after the event become confused with the details of the original memory. For example, in one classic study, participants viewed images showing the use of a screwdriver in a burglary (Loftus & others, 1989). Later, they read a written account of the break-in, but this account featured a hammer instead of a screwdriver. When tested for their memory of the images, 60 percent said that a hammer (the post-event information), rather than a screwdriver (the original information), had been used in the burglary. And they were just as confident of their false memories as they were when recalling their accurate memories of other details of the original event.

source confusion

A memory distortion that occurs when the true source of the memory is forgotten.

Stuart Franklin/Magnum Photos and courtesy of Elizabeth Loftus and Dario Sacchi

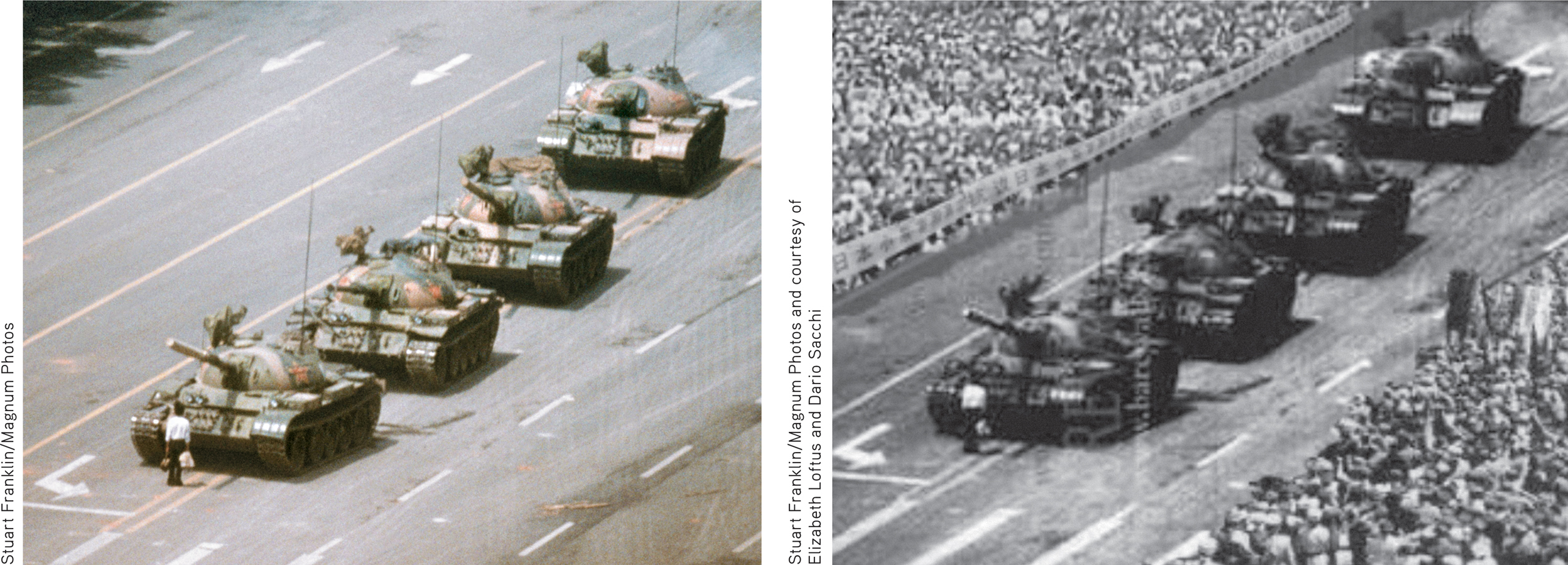

More recently, photographs have been used to demonstrate how false details presented after an original event can become confused with the authentic details of the original memory (Henkel, 2011; Strange & others, 2011). For example, after participants in a study were shown digitally doctored photos of famous news events, such as the violent 1989 Tiananmen Square protests in Beijing, China, details from the fake photos were incorporated into participants’ original memories of the actual news event (Sacchi & others, 2007).

Elizabeth’s story in the Prologue also demonstrated how confusion about the source of a memory can give rise to an extremely vivid, but inaccurate, recollection. Vivid and accurate memories of her uncle’s home, such as the smell of the pine trees and the feel of the lake water, became blended with Elizabeth’s fantasy of finding her mother’s body. The result was a false memory, which is a distorted or fabricated recollection of something that did not actually happen. Nonetheless, the false memory subjectively feels authentic and is often accompanied by all the emotional impact of a real memory.

false memory

A distorted or fabricated recollection of something that did not actually occur.

In essence, all memory is false to some degree. Memory is inherently a reconstructive process, whereby we piece together the past to form a coherent narrative that becomes our autobiography. In the process of reconstructing the past, we color and shape our life’s experiences based on what we know about the world.

—Daniel M. Bernstein & Elizabeth F. Loftus, 2009

SCHEMAS, SCRIPTS, AND MEMORY DISTORTIONSTHE INFLUENCE OF EXISTING KNOWLEDGE ON WHAT IS REMEMBERED

Given that information presented after a memory is formed can change the contents of that memory, let’s consider the opposite effect: Can the knowledge you had before an event occurred influence your later memory of the event? If so, how?

Since you were a child, you have been actively forming mental representations called schemas—organized clusters of knowledge and information about particular topics. The topic can be almost anything—an object (e.g., a wind chime), a setting (e.g., a movie theater), or a concept (e.g., freedom). One kind of schema, called a script, involves the typical sequence of actions and behaviors at a common event, such as eating in a restaurant or taking a plane trip.

schema

(SKEE-muh) An organized cluster of information about a particular topic.

script

A schema for the typical sequence of an everyday event.

Schemas are useful in organizing and forming new memories. Using the schemas you already have stored in long-term memory allows you to quickly integrate new experiences into your knowledge base. For example, consider your schema for “phone.” No longer just a utilitarian communication device, phones can be used to play games, take photographs, and play music or videos. As the capabilities of phones expanded, your schema has changed to incorporate these new attributes. Thus, your schema for “phone” includes smart phones that can send email, cruise the Internet, and provide directions. As new applications become available, you can quickly integrate those functions into your existing schema for “phone.”

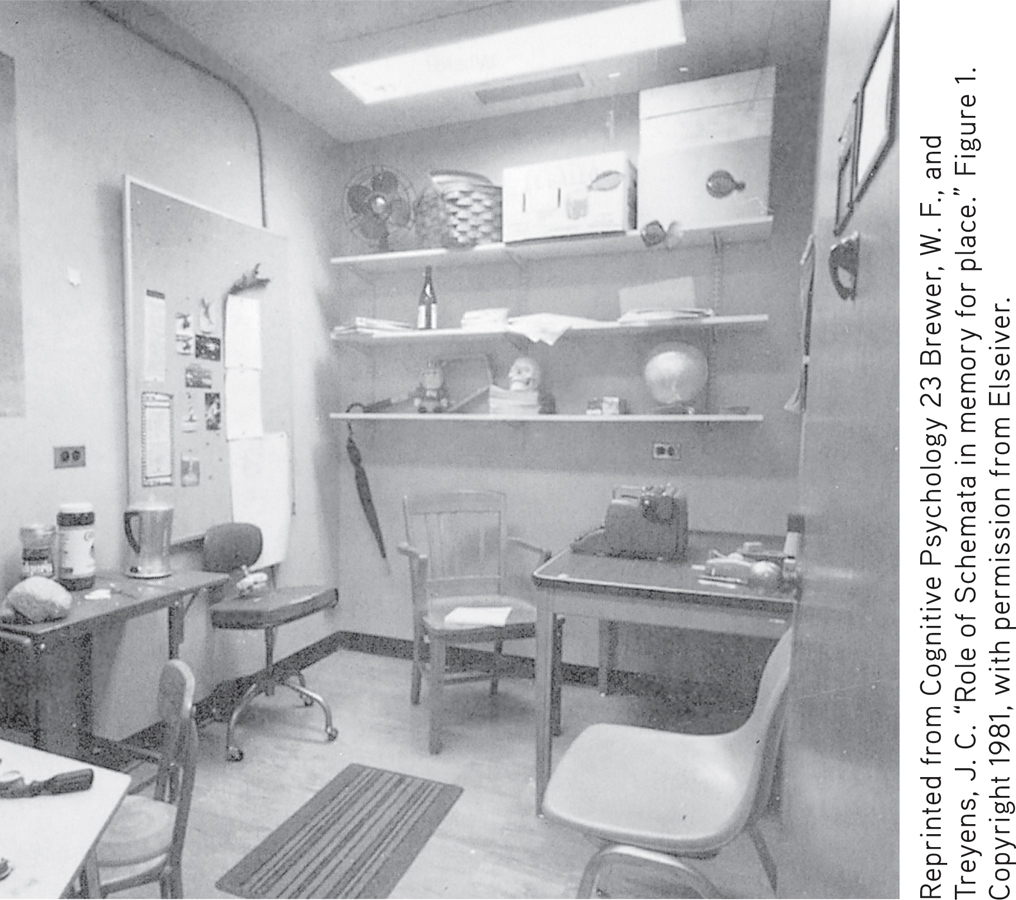

Although useful, schemas can also contribute to memory distortions. In the classic “psychology professor’s office” study described in the photo caption on the right, students erroneously remembered objects that were not actually present but were consistent with their schema of a professor’s office (Brewer & Treyens, 1981). The schemas we have developed can promote memory errors by prompting us to fill in missing details with schema-consistent information.

But what if a situation contains elements that are inconsistent with our schemas or scripts for that situation? Are inconsistent items more likely to stand out in our minds and be better remembered? In a word, yes. Numerous studies have demonstrated that items that are inconsistent with our expectations tend to be better recalled and recognized than items that are consistent with our expectations (see Kleider & others, 2008; Lampinen & others, 2001).

For example, University of Arkansas psychologist James Lampinen and his colleagues (2000) had participants listen to a story about a guy named Jack who performed some everyday activities, like washing his car and taking his dog to the veterinarian for shots. In each scene, Jack performed some actions that would have been consistent with the script (e.g., filling a bucket with soapy water, filling out forms at the vet’s office) and some behaviors that were not part of a typical script for the activity (e.g., spraying the neighbor’s kid with the hose, flirting with the vet’s receptionist). When tested for details of the story, participants were more likely to recognize and remember the atypical actions than the consistent actions.

Much like the subjects in the professor’s office study, participants in Lampinen’s study also experienced compelling false memories. Almost always, the false memories were for actions that would have been consistent with the script—if they had actually happened in the story. For example, some participants vividly remembered that Jack rinsed the car off with a hose or that he put a leash on the dog before taking him to the vet’s office. Neither of those actions occurred in the story.

Later research by psychologists Brent Strickland and Frank Keil (2011) showed that pre-existing schemas can distort memories for events within seconds of viewing them. Study participants watched videos showing athletes kicking, throwing, or hitting a ball. In some videos, the actual point of contact was not shown, just the ball flying into the distance. Nevertheless, within seconds of viewing the video, participants believed that they had seen the causal action that had only been implied by the film. Essentially, they “filled in” the missing moment of contact because, based on prior experience, that interpretation simply made sense.

Forming False Memories

FROM THE PLAUSIBLE TO THE IMPOSSIBLE

KEY THEME

A variety of techniques can create false memories for events that never happened.

KEY QUESTIONS

What is the lost-in-the-mall technique, and how does it produce false memories?

What is imagination inflation, and how has it been demonstrated?

What factors contribute to the formation of false memories?

Up to this point, we’ve talked about how misinformation, source confusion, and the mental schemas and scripts we’ve developed can change or add details to a memory that already exists. However, memory researchers have gone beyond changing a few details here and there. Since the mid-1990s, an impressive body of research has accumulated showing how false memories can be created for events that never happened (Frenda & others, 2011; Loftus & Cahill, 2007). We’ll begin with another Loftus study that has become famous—the lost-in-the-mall study.

!launch!

IMAGINATION INFLATIONREMEMBERING BEING LOST IN THE MALL

In a classic experiment, Loftus and Jacqueline Pickrell (1995) gave each of 24 participants written descriptions of four childhood events that had been provided by a parent or other older relative. Three of the events had really happened, but the fourth was a pseudoevent—a false story about the participant getting lost in a shopping mall. Here’s the gist of the story: At about the age of 5 or 6, the person got lost for an extended period of time in a shopping mall, became very upset and cried, was rescued by an elderly person, and ultimately was reunited with the family. (Family members verified that the participant had never actually been lost in a shopping mall or department store as a child.)

After reading the four event descriptions, the participants wrote down as many details as they could remember about each event. About two weeks later, participants were interviewed and asked to recall as many details as they could about each of the four events. Approximately one to two weeks after that, participants were interviewed a second time and asked once again what they could remember about the four events.

By the final interview, 6 of the 24 participants had created either full or partial memories of being lost in the shopping mall. How entrenched were the false memories for those who experienced them? Even after being debriefed at the end of the study, some of the participants continued to struggle with the vividness of the false memory. “I totally remember walking around in those dressing rooms and my mom not being in the section she said she’d be in,” one participant said (Loftus & Pickrell, 1995).

The research strategy of using information from family members to help create or induce false memories of childhood experiences has been dubbed the lost-in-the-mall technique (Loftus, 2003). By having participants remember real events along with imagining pseudoevents, researchers have created false memories for a wide variety of events. For example, participants have been led to believe that as a child they had been saved by a lifeguard from nearly drowning (Heaps & Nash, 2001). Or that they had knocked over a punch bowl on the bride’s parents at a wedding reception (Hyman & Pentland, 1996).

!launch!

Clearly, then, research has demonstrated that people can develop beliefs and memories for events that definitely did not happen to them. One key factor in the creation of false memories is the power of imagination. Put simply, imagining the past as different from what it was can change the way you remember it. Several studies have shown that vividly imagining an event markedly increases confidence that the event actually occurred in childhood, an effect called imagination inflation (Garry & Polaschek, 2000; Thomas & others, 2003).

imagination inflation

A memory phenomenon in which vividly imagining an event markedly increases confidence that the event actually occurred.

How does imagining an event—even one that never took place—help create a memory that is so subjectively compelling? Several factors seem to be involved. First, repeatedly imagining an event makes the event seem increasingly familiar. People then misinterpret the sense of familiarity as an indication that the event really happened (Sharman & others, 2004).

Second, coupled with the sense of increased familiarity, people experience source confusion. That is, subtle confusion can occur as to whether a retrieved “memory” has a real event—or an imagined event—as its source. Over time, people may misattribute their memory of imagining the pseudoevent as being a memory of the actual event.

Third, the more vivid and detailed the imaginative experience, the more likely it is that people will confuse the imagined event with a real occurrence (Thomas & others, 2003). Vivid sensory and perceptual details can make the imagined events feel more like real events.

Simple manipulations, such as suggestions and imagination exercises, can increase the incidence and realism of false memories. So can vivid memory cues and family photos. TABLE 6.3 summarizes factors known to contribute to the formation of false memories. The ease with which false memories can be implanted is more than just an academic question. It also has some powerful real-world implications. For example, a recent study by Steven Frenda and his colleagues (2013) showed just how easily people’s memories of actual political events could be changed. The online magazine Slate invited readers to participate in a survey about political events (Saletan, 2010).

Factors Contributing to False Memories

| Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Misinformation effect | When erroneous information received after an event leads to distorted or false memories of the event |

| Source | Forgetting or misremembering the true source of a memory |

| Schema distortion | False or distorted memories caused by the tendency to fill in missing memory details with information that is consistent with existing knowledge about a topic |

| Imagination inflation | Unfounded confidence in a false or distorted memory caused by vividly imagining the pseudoevent |

| False familiarity | Increased feelings of familiarity due to repeatedly imagining an event |

| Blending fact and fiction | Using vivid, authentic details to add to the legitimacy and believability of a pseudoevent |

| Suggestion | Hypnosis, guided imagery, or other highly suggestive techniques that can inadvertently or intentionally create vivid false memories |

Think Like a SCIENTIST

If you saw a crime take place, would you be a good witness? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about Eyewitness Testimony.

CRITICAL THINKING

The Memory Wars: Recovered or False Memories?

Repressed memory therapy, recovery therapy, recovered memory therapy, trauma therapy—these are some of the names of a therapy introduced in the 1990s and embraced by many psychotherapists, counselors, social workers, and other mental health workers. Proponents of the therapy claimed they had identified the root cause of a wide assortment of psychological problems: repressed memories of sexual abuse that had occurred during childhood.

This therapeutic approach assumed that incidents of sexual and physical abuse experienced in childhood, especially when perpetrated by a trusted caregiver, were so psychologically threatening that the victims repressed all memories of the experience (Gleaves & others, 2004; McNally & Geraerts, 2009). Despite being repressed, these unconscious memories of unspeakable traumas continued to cause psychological and physical problems, ranging from low self-esteem to eating disorders, substance abuse, and major depressive disorder.

The goal of repressed memory therapy was to help adult incest survivors “recover” their repressed memories of childhood sexual abuse. Reliving these painful experiences would help them begin “the healing process” of working through their anger and other intense emotions (Bass & Davis, 1994). Survivors were encouraged to confront their abusers and, if necessary, break all ties with their abusive families.

The Controversy: The “Recovery” Methods

The validity of the memories recovered in therapy became the center of a highly charged public controversy that has been dubbed “the memory wars” (Loftus, 2004; Patihis & others, 2014). A key issue was the methods used to help people unblock, or recover, repressed memories. Some recovered memory therapists therapy, and other highly suggestive techniques to recover the long-repressed memories (Thayer & Lynn, 2006).

Many patients supposedly recovered memories of repeated incidents of physical and sexual abuse, sometimes beginning in early infancy, ongoing for years, and involving multiple victimizers. Even more disturbing, some patients recovered vivid memories of years of alleged ritual satanic abuse involving secret cults practicing cannibalism, torture, and ritual murder (Loftus & Davis, 2006; Sakheim & Devine, 1992).

In more than twenty-five years of doing several hundred studies involving perhaps 20,000 people, we had distorted a significant portion of the subjects’ memories. And the mechanism by which we can convince people they were lost, frightened, and crying in a mall is not so different than the mechanism by which therapists might unwittingly encourage memories of sexual abuse.

—Elizabeth Loftus (2003)

The Critical Issue: Recovered or False Memories?

Are traumatic memories likely to be repressed? It is well established that in documented cases of trauma, most survivors are troubled by the opposite problem—they cannot forget their traumatic memories (Berntsen & Rubin, 2014). Rather than being unable to remember the experience, trauma survivors suffer from recurring flashbacks, intrusive thoughts and memories of the trauma, and nightmares. This pattern is a key symptom of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which we’ll discuss in Chapter 14.

While it is relatively common for a person to be unable to remember some of the specific details of a traumatic event or to be troubled by memory problems after the traumatic event, such memory problems do not typically include difficulty in remembering the trauma itself (McNally, 2007). Memory researchers agree that a person might experience amnesia for a single traumatic incident but are skeptical that anyone could repress all memories of repeated incidents of abuse, especially when those incidents occurred over a period of several years (McNally & Geraerts, 2009).

Critics of repressed memory therapy contend that many of the supposedly “recovered” memories are actually false memories that were produced by the well-intentioned but misguided use of suggestive therapeutic techniques (Davis & Loftus, 2009). Memory experts object to the use of hypnosis and other highly suggestive techniques to recover repressed memories (Gerrie & others, 2004; McNally & Geraerts, 2009). Understandably so. As you’ve seen in this chapter, compelling research shows the ease with which misinformation, suggestion, and imagination can create vivid—but completely false—memories.

What Conclusions Can Be Drawn?

After years of debate, some areas of consensus have emerged (Allen, 2005; Colangelo, 2007). First, there is no question that physical and sexual abuse in childhood is a serious social problem that also contributes to psychological problems in adulthood (Hillberg & others, 2011).

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that it’s common to completely repress memories of traumatic events, but that such events can be accurately remembered under hypnosis?

Second, some psychologists contend it is possible for memories of childhood abuse to be completely forgotten, only to surface many years later in adulthood (Colangelo, 2007). Nevertheless, it’s clear that repressed memories that have been recovered in psychotherapy need to be regarded with caution (Piper & others, 2008).

Third, the details of memories can be distorted with disturbing ease (Herndon & others, 2014). Consequently, the use of highly suggestive techniques to recover memories of abuse raises serious concerns about the accuracy of such memories. As we have noted repeatedly in this chapter, a person’s confidence in a memory is no guarantee that the memory is indeed accurate. False or fabricated memories can seem just as detailed, vivid, and real as accurate ones (Gerrie & others, 2004; Lampinen & others, 2005).

Fourth, keep in mind that every act of remembering involves reconstructing a memory. Remembering an experience is not like replaying a movie captured with your cell phone. Memories can change over time. Without our awareness, memories can grow and evolve, sometimes in unexpected ways.

Finally, psychologists and other therapists have become more aware of the possibility of inadvertently creating false memories in therapy (Davis & Loftus, 2009). Guidelines have been developed to help mental health professionals avoid unintentionally creating false memories in clients (American Psychological Association Working Group, 1998; Colangelo, 2007).

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

Why is it difficult to determine the accuracy of a “memory” that is recovered in therapy?

How could the phenomenon of source confusion be used to explain the production of false memories?

As part of the survey, five photographs were shown. In each set of five photos, one had been doctored so that it showed an event that had never actually occurred. For example, one phony photo showed Barack Obama shaking hands with Iran president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. (In reality, Obama has never been in the same room with Ahmadinejad.)

Over 5,000 Slate readers participated in the study. When asked how they felt about each of the five political events depicted, fully 50% reported that they remembered the false event happening—and more than half of this group said that they remembered seeing it on the news! As the researchers wrote, “Slate readers became participants in the largest false memory experiment ever conducted”—one which demonstrated how easy it is to create false memories for events that never happened. Can the same be true of memories for personal, rather than political, history? We explore this question in the Critical Thinking box on a highly charged controversy that has been dubbed “the memory wars.”

However, we don’t want to leave you with the impression that all memories are highly unreliable. In reality, most memories tend to be quite accurate for the gist of what occurred. When memory distortions occur spontaneously in everyday life, they usually involve limited bits of information.

Still, the surprising ease with which memory details can become distorted is unnerving. Distorted memories can ring true and feel just as real as accurate memories (Bernstein & Loftus, 2009; Clifasefi& others, 2007). In the chapter Prologue, you saw how easily Elizabeth Loftus created a false memory. You also saw how quickly she became convinced of the false memory’s authenticity and the strong emotional impact it had on her. Rather than being set in stone, human memories are more like clay: They can change shape with just a little bit of pressure.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that once formed, memories can’t change?

CONCEPT REVIEW 6.2

Factors That Affect Retrieval and Forgetting

Select the correct answer.

Question 6.10

1. Lila discovered an old box of childhood toys stored in her attic. As she sorted through the box, she was flooded with memories of long-forgotten friends and experiences, including her first day of school and the games she played with neighborhood children. The toys were acting as:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.11

2. Juan always studied alone in the college library. He was surprised when he had difficulty remembering some information during his final exam, which he took in a large gymnasium with several hundred other students. One explanation for his forgetting information that he had studied could be:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.12

3. At a family reunion, Aunt Edna was surprised when her nephew Andrew said he couldn’t remember falling and putting his hand through a window 20 years previously, when he was 6 years old. But the more Andrew thought about the incident, the more the memory came back to him, and he began recalling vivid details of the scene. Only later did Andrew learn from his mother that Aunt Edna was wrong—she had confused Andrew with another nephew, Logan. Andrew had probably experienced:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.13

4. Professor Ivanovich has many vivid memories of her students from last semester and can recall most of their names. Because of ________, she is having problems remembering her new students’ names this semester.

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Question 6.14

5. Rob has a very vivid memory of a bad traffic accident that occurred near his home when he was a child. His mother, however, claims that Rob couldn’t have witnessed the incident because he was in bed, asleep, when it occurred, and he had learned about the accident from television news reports. Rob’s false memory is probably the result of:

| A. |

| B. |

| C. |

| D. |

Test your understanding of Forgetting and Imperfect Memories with

.

.