8.7 PSYCH FOR YOUR LIFE

Turning Your Goals into Reality

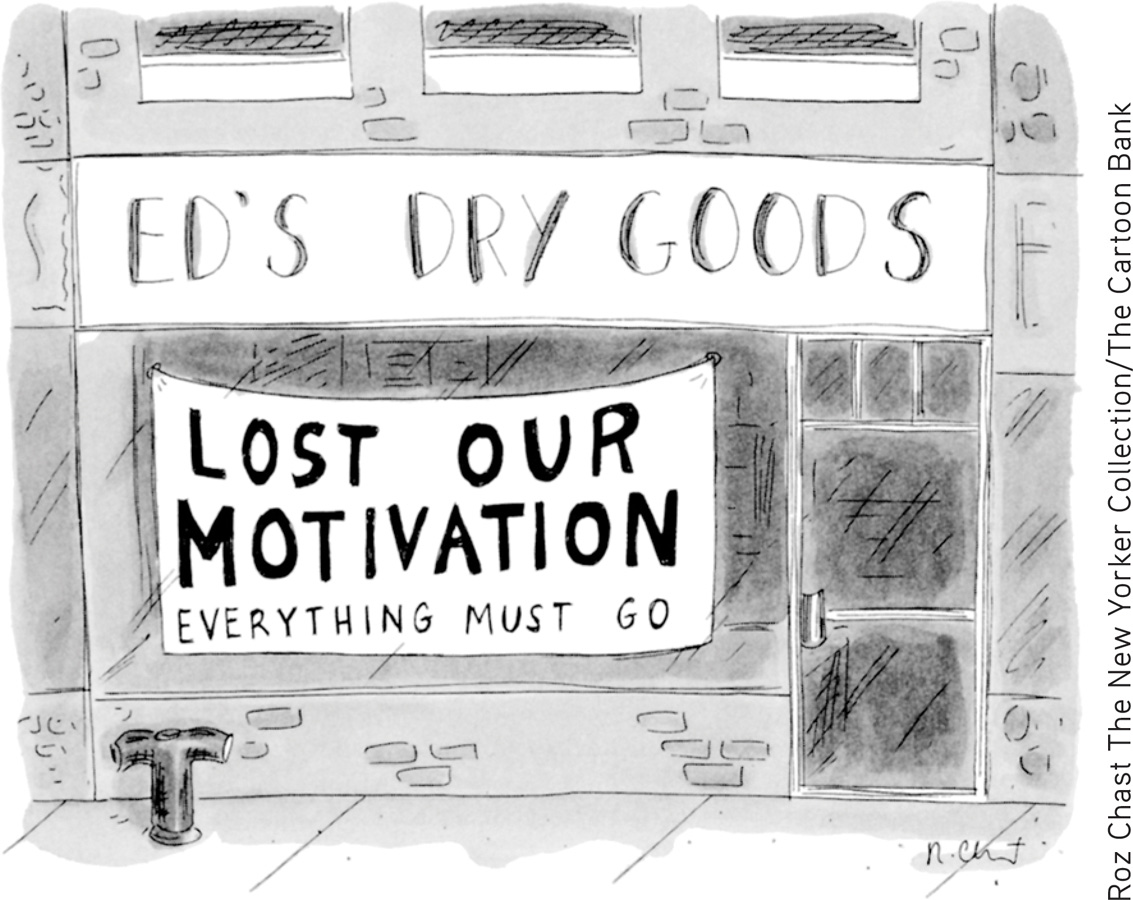

Most people can identify different aspects of their lives they’d like to change. Identifying goals we’d like to achieve is usually easy. Successfully accomplishing these goals is the tricky part. Fortunately, psychological research has identified several strategies and suggestions that can help you get motivated, act, and achieve your goals.

Self-Efficacy: Optimistic Beliefs About Your Capabilities

Your motivation to strive for achievement is closely linked to what you believe about your ability to produce the necessary or desired results in a situation. This is what psychologist Albert Bandura (1997, 2006) calls self-efficacy—the degree to which you are convinced of your ability to effectively meet the demands of a particular situation.

self-efficacy

The beliefs that people have about their ability to meet the demands of a specific situation; feelings of self-confidence.

Bandura (1997, 2006) has found that if you have an optimistic sense of self-efficacy, you will approach a difficult task as a challenge to be mastered. You will also exert strong motivational effort, persist in the face of obstacles, and look for creative ways to overcome obstacles. If you see yourself as competent and capable, you are more likely to strive for higher personal goals (Bayer & Gollwitzer, 2007; Wood & Bandura, 1991).

People tend to avoid challenging situations or tasks that they believe exceed their capabilities (Bandura, 2008). If self-doubts occur, motivation quickly dwindles because the task is perceived as too difficult or threatening. So how do you build your sense of self-efficacy, especially in situations in which your confidence is shaky?

According to Bandura (1991, 2006), the most effective way to strengthen your sense of self-efficacy is through mastery experiences—experiencing success at moderately challenging tasks in which you have to overcome obstacles and persevere. As you tackle a challenging task, you should strive for progressive improvement rather than perfection on your first attempt. Understand that setbacks serve a useful purpose in teaching that success usually requires sustained effort. If you experienced only easy successes, you’d be more likely to become disappointed and discouraged, and to abandon your efforts when you did experience failure.

A second strategy is social modeling, or observational learning. In some situations, the motivation to succeed is present, but you lack the knowledge of exactly how to achieve your goals. In such circumstances, it can be helpful to observe and imitate the behavior of someone who is already competent at the task you want to master (Bandura, 1986, 1990). For example, if you’re not certain how to prepare effectively for a test or a class presentation, talk with fellow students who are successful in doing this. Ask how they study and what they do when they have difficulty understanding material. Knowing what works is often the critical element in ensuring success.

Implementation Intentions: Turning Goals into Actions

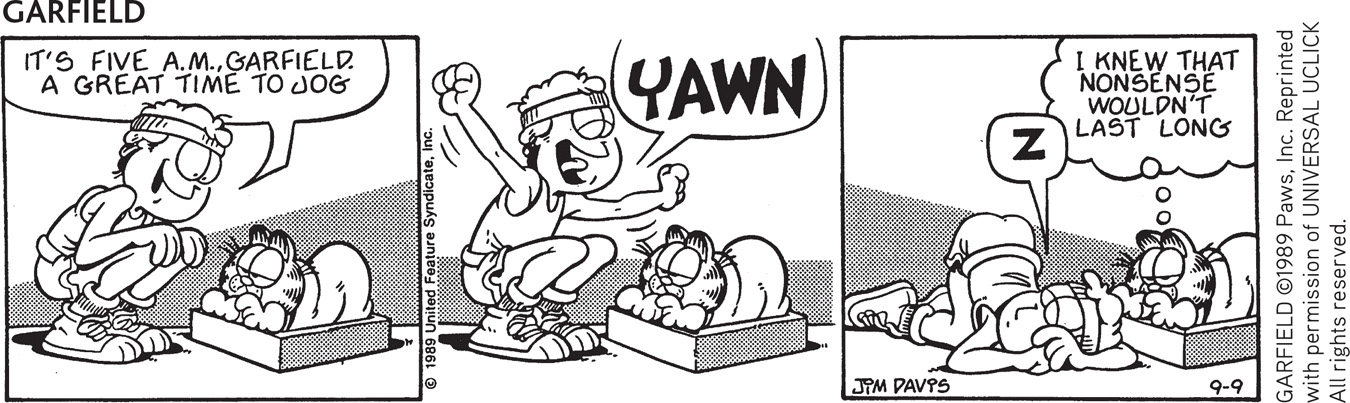

Suppose your sense of self-efficacy is strong, but you still have trouble putting your intentions into action. For example, have you ever made a list of New Year’s resolutions and looked back at it six months later? If you’re like most people, you’ll wonder what went wrong.

How can you bridge the gap between good intentions and effective, goal-directed behavior? German psychologist Peter Gollwitzer (1999) points out that many people have trouble initiating the actions required to fulfill their goals and then persisting in these behaviors until the goals are achieved. Gollwitzer and his colleagues (2008, 2010) have identified some simple yet effective techniques that help people translate their good intentions into actual behavior.

Step 1: Form a goal intention.

This step involves translating vague, general intentions (“I’m going to do my best”) into a specific, concrete, and binding goal. Express the specific goal in terms of “I intend to achieve _____,” filling in the blank with the particular behavior or outcome that you wish to achieve. For example, suppose you resolve to exercise more regularly. Transform that general goal into a much more specific goal intention, such as “I intend to work out at the campus gym on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.” Forming the specific goal intention enhances your sense of personal commitment to the goal, and it also heightens your sense of obligation to realize the goal.

Step 2: Create implementation intentions.

This step involves making a specific plan for turning your good intention into reality. The trick is to specify exactly where, when, and how you will carry out your intended behavior. Mentally link the intended behaviors to specific situational cues, such as saying, “After my psychology class, I will go to the campus athletic center and work out for 45 minutes.” By linking the behavior to specific situational cues, you’re more likely to initiate the goal behavior when the critical situation is encountered (Webb & Sheeran, 2007). The ultimate goal of implementation intentions is to create a new automatic link between a specific situation and the desired behavior—and ultimately, to create new habits or routines in your life (Adriaanse & others, 2011).

As simple as this seems, research has demonstrated that forming specific implementation intentions is very effective (Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006; Parks-Stamm & others, 2007). For example, one study involved student volunteers with no enticement for participating in the research, such as money or course credit. Just before the students left for the holidays, they were instructed to write an essay describing how they spent Christmas Eve. The essay had to be written and mailed within two days after Christmas Eve.

Half of the participants were instructed to write out specific implementation intentions describing exactly when and where they would write the report during the critical 48-hour period. They were also instructed to visualize the chosen opportunity and mentally commit themselves to it.

The other half of the participants were not asked to identify a specific time or place, but just instructed to write and mail the report within the 48 hours. The results? Of those in the implementation intention group, 71 percent wrote and mailed the report by the deadline. Only 32 percent of the other group did so (Gollwitzer & Brandstätter, 1997).

Mental Rehearsal: Visualize the Process

The mental images you create in anticipation of a situation can strongly influence your sense of self-efficacy and self-control as well as the effectiveness of your implementation intentions (Knäuper & others, 2009). For example, students sometimes undermine their own performance by vividly imagining their worst fears, such as becoming overwhelmed by anxiety during a class presentation or going completely blank during a test. However, the opposite is also possible. Mentally visualizing yourself dealing effectively with a situation can enhance your performance (Conway & others, 2004; Libby & others, 2007). Athletes, in particular, are aware of this and mentally rehearse their performance prior to competition.

So strive to control your thoughts in an optimistic way by mentally focusing on your capabilities and a positive outcome, not your limitations and worst fears. The key here is not just imagining a positive outcome. Instead, imagine and mentally rehearse the process—the skills you will effectively use and the steps you will take—to achieve the outcome you want. Go for it!