9.4 Development During Infancy and Childhood

KEY THEME

Although physically helpless, newborn infants are equipped with reflexes and sensory capabilities that enhance their chances for survival.

KEY QUESTIONS

How do the senses and the brain develop after birth?

What roles do temperament and attachment play in social and personality development?

What are the stages of language development?

The newly born infant enters the world with an impressive array of physical and sensory capabilities. Initially, his behavior is mostly limited to reflexes that enhance his chances for survival. Touching the newborn’s cheek triggers the rooting reflex—the infant turns toward the source of the touch and opens his mouth. Touching the newborn’s lips evokes the sucking reflex. If you put a finger on each of the newborn’s palms, he will respond with the grasping reflex—the baby will grip your fingers so tightly that he can be lifted upright. As motor areas of the infant’s brain develop over the first year of life, the rooting, sucking, and grasping reflexes are replaced by voluntary behaviors.

The newborn’s senses—vision, hearing, smell, and touch—are keenly attuned to people. In a classic study, Robert Fantz (1961) demonstrated that the image of a human face holds the newborn’s gaze longer than do other images. Other researchers have also confirmed the newborn’s visual preference for the human face (Pascalis & Kelly, 2009). Newborns only 10 minutes old will turn their heads to continue gazing at the image of a human face as it passes in front of them, but they will not visually follow other images (Turati, 2004).

And, newborns quickly learn to differentiate between their mothers and strangers. Within just hours of their birth, newborns display a preference for their mother’s voice and face over that of a stranger (Bushnell, 2001). For their part, mothers become keenly attuned to their infant’s appearance, smell, and even skin texture. Fathers, too, are able to identify their newborn from a photograph after just minutes of exposure (Bader & Phillips, 2002).

Vision is the least developed sense at birth. A newborn infant is extremely nearsighted, meaning she can see close objects more clearly than distant objects. The optimal viewing distance for the newborn is about 6 to 12 inches, the perfect distance for a nursing baby to focus easily on her mother’s face and make eye contact. Nevertheless, the infant’s view of the world is pretty fuzzy for the first several months, even for objects that are within close range.

The interaction between adults and infants seems to compensate naturally for the newborn’s poor vision. When adults interact with very young infants, they almost always position themselves so that their face is about 8 to 12 inches away from the baby’s face. Adults also have a strong natural tendency to exaggerate head movements and facial expressions, such as smiles and frowns, again making it easier for the baby to see them.

Physical Development

By the time infants begin crawling, at about 7 to 8 months of age, their view of the world, including distant objects, will be as clear as that of their parents. The increasing maturation of the infant’s visual system reflects the development of her brain. At birth, her brain is an impressive 25 percent of its adult weight. In contrast, her birth weight is only about 5 percent of her eventual adult weight. During infancy, her brain will grow to about 75 percent of its adult weight, while her body weight will reach only about 20 percent of her adult weight.

During the prenatal period, the top of the body develops faster than the bottom. For example, the head develops before the legs. If you’ve ever watched a 6-week old baby struggling to lift her head up, or a 3-month old baby pulling herself along the floor by her arms, you’ve probably noticed that an infant’s motor skills also develop unevenly, and follow the same general pattern. The word cephalocaudal literally means “head to tail,” and the term cephalocaudal pattern refers to the fact that physical and motor skill development tends to follow a “top to bottom” sequence. The infant develops control over her head, chest, and arms before developing control over the lower part of her body and legs (Kopp, 2011).

A second pattern is the proximodistal trend, which refers to the tendency of infants to develop motor control from the center of their bodies outwards. Babies gain control over their abdomen before they gain control over their elbows, knees, hands, or feet.

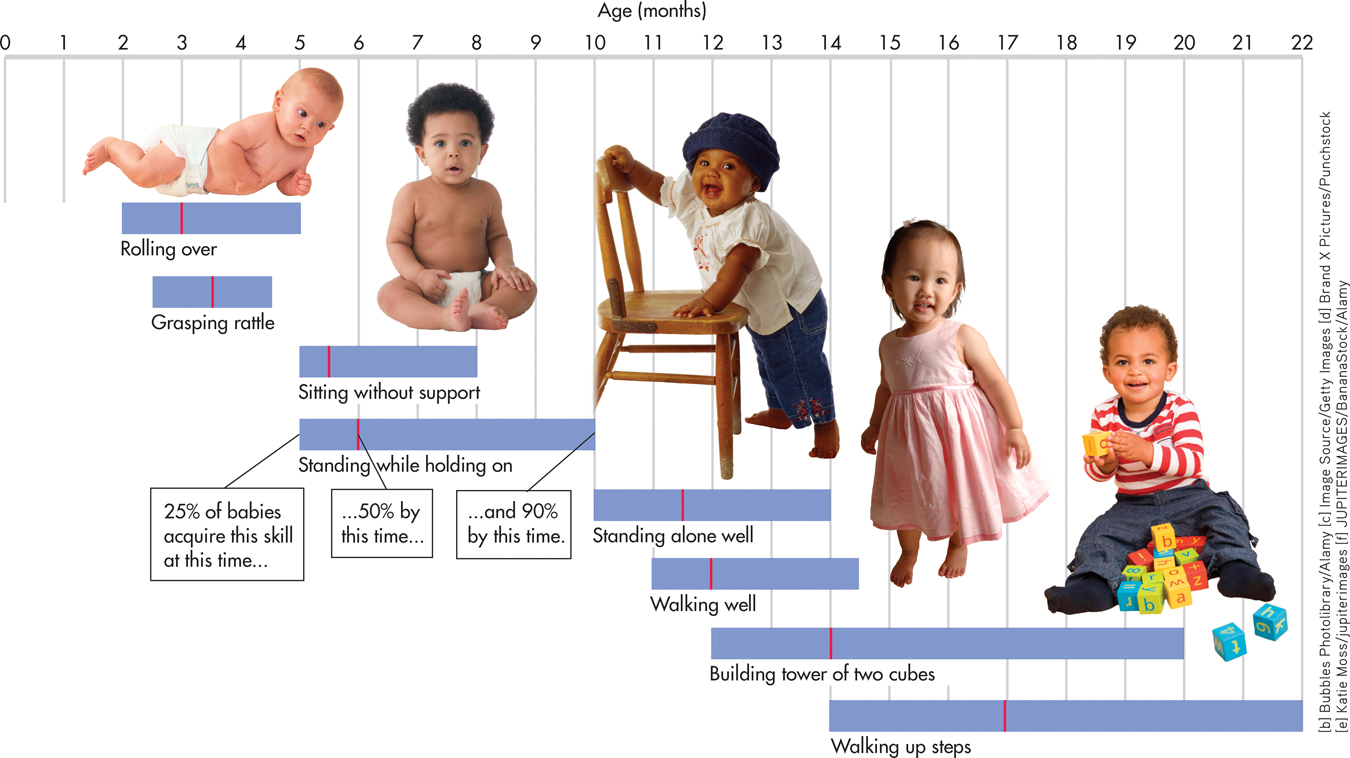

The basic sequence of motor skill development is universal, but the average ages can be a little deceptive (see FIGURE 9.3). As any parent knows, infants vary a great deal in the ages at which they master each skill. For example, virtually all infants are walking well by 15 months of age, but some infants will walk as early as 10 months. Each infant has her own timetable of physical maturation and developmental readiness to master different motor skills.

Social and Personality Development

From birth, forming close social and emotional relationships with caregivers is essential to the infant’s physical and psychological well-being. Although physically helpless, the young infant does not play a passive role in forming these relationships. As you’ll see in this section, the infant’s individual traits play an important role in the development of the relationship between infant and caregiver.

CULTURE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

Where Does the Baby Sleep?

In most U.S. families, infants sleep in their own beds (Mindell & others, 2010a). It may surprise you to discover that the United States is very unusual in this respect. In one survey of 100 societies, the United States was the only one in which babies slept in separate rooms. Another survey of 136 societies found that in two-thirds of the societies, infants slept in the same beds as their mothers. In the remainder, infants generally slept in the same room as their mothers (Morelli & others, 1992).

In one of the few in-depth studies of co-sleeping in different cultures, Gilda Morelli and her colleagues (1992) compared the sleeping arrangements of several middle-class U.S. families with those of Mayan families in a small town in Guatemala. They found that babies in the Mayan families slept with their mothers until they were 2 or 3, usually until another baby was about to be born. At that point, toddlers moved to the bed of another family member, usually the father or an older sibling. Children continued to sleep with other family members throughout childhood.

Mayan mothers were shocked when the American researchers told them that infants in the United States slept alone and often in a different room from their parents. They believed that the practice was cruel and unnatural, and would have negative effects on the infant’s development.

When infants and toddlers sleep alone, bedtime marks a separation from their families. To ease the child’s transition to sleeping, “putting the baby to bed” often involves lengthy bedtime rituals, including rocking, singing lullabies, or reading stories (Morrell & Steele, 2003). Small children take comforting items, such as a favorite blanket or teddy bear, to bed with them to ease the stressful transition to falling asleep alone. The child may also use his “security blanket” or “cuddly” to comfort himself when he wakes up in the night, as most small children do.

In contrast, the Mayan babies did not take cuddly items to bed, and no special routines marked the transition between wakefulness and sleep. Mayan parents were puzzled by the very idea. Instead, the Mayan babies simply went to bed when their parents did or fell asleep in the middle of the family’s social activities. Morelli and her colleagues (1992) found that the different sleeping customs of the U.S. and Mayan families reflect different cultural values. Some of the U.S. babies slept in the same room as their parents when they were first born, which the parents felt helped foster feelings of closeness and emotional security in the newborns. Nonetheless, most of the U.S. parents moved their babies to a separate room when they felt that the babies were ready to sleep alone, usually by the time they were 3 to 6 months of age. These parents explained their decision by saying that it was time for the baby to learn to be “independent” and “self-reliant.”

In contrast, the Mayan parents felt that it was important to develop and encourage the infant’s feelings of interdependence with other members of the family. Thus, in both Mayan and U.S. families, sleeping arrangements reflect cultural goals for child rearing and cultural values for relations among family members.

TEMPERAMENTAL QUALITIESBABIES ARE DIFFERENT!

Infants come into the world with very distinct and consistent behavioral styles. Some babies are consistently calm and easy to soothe. Other babies are fussy, irritable, and hard to comfort. Some babies are active and outgoing; others seem shy and wary of new experiences. Psychologists refer to these inborn predispositions to consistently behave and react in a certain way as an infant’s temperament.

temperament

Inborn predispositions to consistently behave and react in a certain way.

Interest in infant temperament was triggered by a classic longitudinal study launched in the 1950s by psychiatrists Alexander Thomas and Stella Chess. The focus of the study was on how temperamental qualities influence adjustment throughout life. Chess and Thomas rated young infants on a variety of characteristics, such as activity level, mood, regularity in sleeping and eating, and attention span. They found that about two-thirds of the babies could be classified into one of three broad temperamental patterns: easy, difficult, and slow-to-warm-up. The remaining third of the infants were characterized as average babies because they did not fit neatly into one of these three categories (Thomas & Chess, 1977).

Easy babies readily adapt to new experiences, generally display positive moods and emotions, and have regular sleeping and eating patterns. Difficult babies tend to be intensely emotional, are irritable and fussy, and cry a lot. They also tend to have irregular sleeping and eating patterns. Slow-to-warm-up babies have a low activity level, withdraw from new situations and people, and adapt to new experiences very gradually. After studying the same children from infancy through childhood, Thomas and Chess (1986) found that these broad patterns of temperamental qualities are remarkably stable.

Other temperamental patterns have been identified. For example, after decades of research, Jerome Kagan (2010a, b) classified temperament in terms of reactivity. High-reactive infants react intensely to new experiences, strangers, and novel objects. They tend to be tense, fearful, and inhibited. At the opposite pole are low-reactive infants, who tend to be calmer, uninhibited, and bolder. Sociable rather than shy, low-reactive infants are more likely to show interest than fear when exposed to new people, experiences, and objects.

Virtually all temperament researchers agree that individual differences in temperament have a genetic and biological basis (Gagne & others, 2009). However, researchers also agree that environmental experiences can modify a child’s basic temperament (Stack & others, 2010). As Kagan (2004) points out, “Temperament is not destiny. Many experiences will affect high and low reactive infants as they grow up. Parents who encourage a more sociable, bold persona and discourage timidity will help their high reactive children develop a less-inhibited profile.”

Because cultural attitudes affect child-rearing practices, infant temperament can also be affected by cultural beliefs (Kagan, 2010a, b). For example, cross-cultural studies of temperament have found that infants in the United States generally displayed more positive emotion than Russian or Asian infants (Molitor & Hsu, 2011). Why? U.S. parents tend to value and encourage expressions of positive emotions, such as smiling and laughing, in their babies. In contrast, parents in other cultures, including those of Russia and many Asian countries, place less emphasis on the importance of positive emotional expression. Thus, the development of temperamental qualities is yet another example of the complex interaction among genetic and environmental factors.

ATTACHMENTFORMING EMOTIONAL BONDS

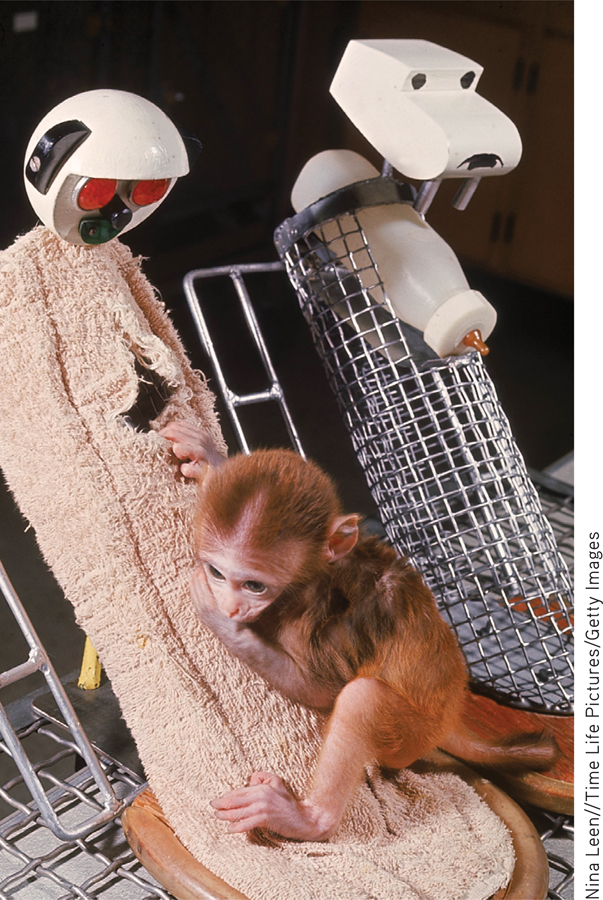

Not long after World War II, Austrian psychiatrist Rene Spitz dramatically showed the detrimental effects of institutionalization on children who were deprived of a relationship with a warm, loving caregiver. Although provided with adequate nutrition, many infants failed to thrive. Psychologist Harry Harlow (1905–

Harlow’s findings helped stimulate research on the emotional bond that forms between infants and their caregivers, especially parents, during the first year of life, which is called attachment. As conceptualized by attachment theorist John Bowlby (1969, 1988) and psychologist Mary D. Salter Ainsworth (1979), attachment relationships serve important functions throughout infancy and, indeed, the lifespan. Ideally, the parent or caregiver functions as a secure base for the infant, providing a sense of comfort and security—a safe haven from which the infant can explore and learn about the environment. According to attachment theory, an infant’s ability to thrive physically and psychologically depends in large part on the quality of attachment (Ainsworth & others, 1978).

attachment

The emotional bond that forms between an infant and caregiver(s), especially his or her parents.

Generally, when parents are consistently warm, responsive, and sensitive to their infant’s needs, the infant develops a secure attachment to her parents (Belsky, 2006). The infant’s expectation that her needs will be met by her caregivers is the most essential ingredient in forming a secure attachment to them. And, studies have confirmed that sensitivity to the infant’s needs is associated with secure attachment across diverse cultures (van Ijzendoorn & Sagi-Schwartz, 2008; Vaughn & others, 2007).

In contrast, insecure attachment may develop when an infant’s parents are neglectful, inconsistent, or insensitive to his moods or behaviors. Insecure attachment seems to reflect an ambivalent or detached emotional relationship between an infant and his parents (Ainsworth, 1979; Isabella & others, 1989).

How do researchers measure attachment? The most commonly used procedure, called the Strange Situation, was devised by Ainsworth. The Strange Situation is typically used with infants who are between 1 and 2 years old (Ainsworth & others, 1978). In this technique, the baby and his mother are brought into an unfamiliar room with a variety of toys. A few minutes later, a stranger enters the room. The mother stays with the baby for a few moments, then departs, leaving the baby alone with the stranger. After a few minutes, the mother returns, spends a few minutes in the room, leaves, and returns again. Through a one-way window, observers record the infant’s behavior throughout this sequence of separations and reunions.

Psychologists assess attachment by observing the child’s behavior toward his mother during the Strange Situation procedure. When his mother is present, the securely attached baby will use her as a “secure base” from which to explore the new environment, periodically returning to her side. He will show distress when his mother leaves the room and will greet her warmly when she returns. A securely attached baby is easily soothed by his mother (Ainsworth & others, 1978; Lamb & others, 1985).

In contrast, an insecurely attached infant is less likely to explore the environment, even when her mother is present. In the Strange Situation, insecurely attached infants may appear either very anxious or completely indifferent. Such infants tend to ignore or avoid their mothers when they are present. Some insecurely attached infants become extremely distressed when their mothers leave the room. When insecurely attached infants are reunited with their mothers, they are hard to soothe and may resist their mothers’ attempts to comfort them.

In studying attachment, psychologists have typically focused on the infant’s bond with the mother, since the mother is often the infant’s primary caregiver. Still, it’s important to note that most fathers are also directly involved with the basic care of their infants and children. As is the case with mothers, children are more likely to be securely attached to fathers who are involved with their care and sensitive to their needs (Brown & others, 2012). In homes where both parents are present, children who are attached to one parent are usually also attached to the other (Furman & Simon, 2004). Finally, infants are capable of forming attachments to other consistent caregivers in their lives, such as relatives or workers at a day-care center. Thus, an infant can form multiple attachments.

The quality of attachment during infancy is associated with a variety of long-term effects (Bornstein, 2014; Malekpour, 2007). Preschoolers with a history of being securely attached tend to be more prosocial, empathic, and socially competent than are preschoolers with a history of insecure attachment (Rydell & others, 2005). In middle childhood, children with a history of secure attachment in infancy are better adjusted and have higher levels of social and cognitive development than do children who were insecurely attached in infancy (Kerns & others, 2007; Kerns & Richardson, 2005; Stams & others, 2002). Adolescents who were securely attached in infancy have fewer problems, do better in school, and have more successful relationships with their peers than do adolescents who were insecurely attached in infancy (Laible, 2007; Sroufe, 2002; Sweeney, 2007).

Because attachment in infancy seems to be so important, psychologists have extensively investigated the impact of day care on attachment. Later in the chapter, we’ll take a close look at this issue (see p. 388).

Language Development

Probably no other accomplishment in early life is as astounding as language development. By the time a child reaches 3 years of age, he will have learned thousands of words and the complex rules of his language.

According to linguist Noam Chomsky (1965), every child is born with a biological predisposition to learn language—any language. In effect, children possess a “universal grammar”—a basic understanding of the common principles of language organization. Infants are innately equipped not only to understand language but also to extract grammatical rules from what they hear. The key task in the development of language is to learn a set of grammatical rules that allows the child to produce an unlimited number of sentences from a limited number of words.

At birth, infants can distinguish among the speech sounds of all the world’s languages, no matter what language is spoken in their homes (Kuhl, 2004; Werker & Desjardins, 1995). Infants lose this ability by 10–

ENCOURAGING LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT

Just as infants seem to be biologically programmed to learn language, parents are predisposed to encourage language development by the way they speak to infants and toddlers. People in every culture, especially parents, use a style of speech called motherese, parentese, or infant-directed speech, with babies (Bryant & Barrett, 2007; Kuhl, 2004).

Infant-directed speech is characterized by very distinct pronunciation, a simplified vocabulary, short sentences, high pitch, and exaggerated intonation and expression. Content is restricted to topics that are familiar to the child, and “baby talk” is often used—simplified words such as “go bye-bye” and “night-night.” Often, questions are asked, encouraging a response from the infant (Fernald, 1992).

The adult use of infant-directed speech seems to be instinctive. Deaf mothers who use sign language modify their hand gestures when they communicate with infants and toddlers in a way that is very similar to the infant-directed speech of hearing mothers (Koester & Lahti-Harper, 2010).

And, infants seem to prefer infant-directed speech to a more adult conversational style. The positive response from the young child makes adults more likely to use parentese (Fernald, 1985; Smith & Trainor, 2008). As infants mature, the speech patterns of parents change to fit the child’s developing language abilities (McRoberts & others, 2009).

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that talking “baby talk” to infants and toddlers won’t harm their language development?

THE COOING AND BABBLING STAGE OF LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT

As with many other aspects of development, the stages of language development appear to be universal (Kuhl, 2004). In virtually every culture, infants follow the same sequence of language development and at roughly similar ages.

At about 3 months of age, infants begin to “coo,” repeating vowel sounds such as ahhhhh or ooooo, varying the pitch up or down. At about 5 months of age, infants begin to babble. They add consonants to the vowels and string the sounds together in sometimes long-winded productions of babbling, such as ba-ba-ba-ba, de-de-de-de, or ma-ma-ma-ma.

When infants babble, they are not simply imitating adult speech. Infants all over the world use the same sounds when they babble, including sounds that do not occur in the language of their parents and other caregivers. At around 9 months of age, babies begin to babble more in the sounds specific to their language. Babbling, then, seems to be a biologically programmed stage of language development (Gentilucci & Dalla Volta, 2007; Petitto & others, 2004).

THE ONE-WORD STAGE OF LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT

Long before babies become accomplished talkers, they understand much of what is said to them. Before they are a year old, most infants can understand simple commands, such as “Bring Daddy the block,” even though they cannot say the words bring, Daddy, or block. This reflects the fact that an infant’s comprehension vocabulary (the words she understands) is much larger than her production vocabulary (the words she can say). Generally, infants acquire comprehension of words more than twice as fast as they learn to speak new words.

comprehension vocabulary

The words that are understood by an infant or child.

production vocabulary

The words that an infant or child understands and can speak.

Somewhere around their first birthday, infants produce their first real words. First words usually refer to concrete objects or people that are important to the child, such as mama, daddy, or ba-ba (bottle). First words are also often made up of the syllables that were used in babbling.

During the one-word stage, babies use a single word and vocal intonation to stand for an entire sentence. With the proper intonation and context, baba can mean “I want my bottle!” “There’s my bottle!” or “Where’s my bottle?”

SCIENCE VERSUS PSEUDOSCIENCE

Can a DVD Program Your Baby to Be a Genius?

It’s a marketing phenomenon: Videos developed specifically for infants and very young toddlers, with catchy titles like Smart Baby, Brainy Baby, and Baby Einstein. When the first Baby Einstein video was released in 1997, ads claimed that it promoted infant brain development (Bronson & Merryman, 2009).

Although the makers of Baby Einstein no longer feature such explicit claims in their advertising, most companies that market baby media either imply or state outright that their products are educational and will help infants learn (Wartella & others, 2010). No doubt fueled by the hope that viewing such media would benefit their babies, parents spend hundreds of millions of dollars annually on baby video products in the United States alone (DeLoache & others, 2010; Rideout, 2007).

But how effective are such videos? Do infants learn from watching them? Let’s look at the evidence.

The first surprise came from a large study that showed that viewing baby media was actually negatively correlated with vocabulary growth in infants. Developmental psychologist Frederick J. Zimmerman and his colleagues (2007) found that babies who never watched “educational” videos knew more words than babies who did. In fact, the more time infants spent watching baby media, the fewer words they knew.

Interestingly, the deficit in language skills was associated only with watching media designed for infant learning—and not other types of television or video. Baby media, the researchers pointed out, have short scenes, anonymous voice-overs rather than talking characters, and visually engaging but disconnected images. In contrast, shows like Sesame Street, which feature recognizable characters and a rich narrative context, have been shown to have educational benefit (Richert & others, 2011; Zimmerman & others, 2007).

One potential drawback of this study was that it was correlational and relied heavily on parent surveys. So, developmental psychologist Judy DeLoache and her colleagues (2010) designed a rigorously controlled experiment in which the infants would be objectively tested for their knowledge of the specific words that were taught on a popular video.

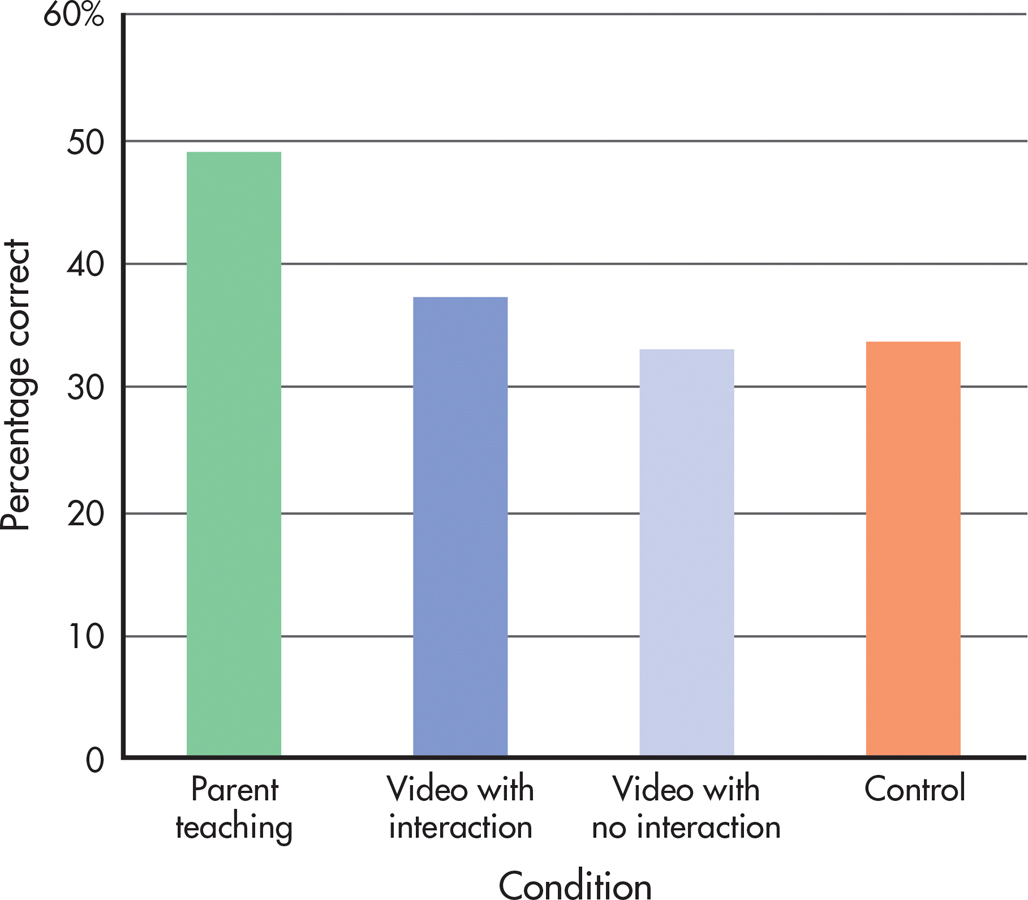

Twelve- to 18-month-old infants were randomly assigned to four groups:

In the video-with-no-interaction condition, the children watched the DVD alone at least five times a week over a 4-week period.

In the video-with-interaction condition, the children watched the DVD with a parent for the same amount of time.

In the parent-teaching condition, the children had no exposure to the video at all. Instead, the parents were given a list of the 25 common words featured on the video and were instructed to “try to teach your child as many of these words as you can in whatever way seems natural to you.”

The parents were not instructed to try to teach them the words. Instead, they were simply tested for their word knowledge before and after the 4-week period.

Why was including a control condition so important? Put simply, because children naturally learn a lot of words during this period of development. Thus, the control condition provided a benchmark of normal vocabulary growth against which the experimental groups could be compared.

What were the results? As shown in the graph, babies learned the most words from interacting with their parents. In contrast, despite extensive exposure to a video designed to teach them specific words, infants in the video groups did not learn any more new words than did children with no exposure to the video at all.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that educational videos, like Baby Einstein, help babies learn how to talk?

Was it because the infants found the videos boring, or didn’t pay attention to them? No. Parents reported that their babies were mesmerized by the program. However, in an interesting twist, DeLoache and her colleagues (2010) found that there was no correlation between how much the parents thought their child learned from the video and how much their child had actually learned. However, the more parents liked the video, the more they thought their child had learned from it.

This finding may help explain the many enthusiastic testimonials in marketing materials for baby media. Even though there was no difference in how many words were learned, parents who had a favorable attitude toward the video thought that their children had learned more because of viewing it. One possible explanation is illusory correlation: Parents may misattribute normal developmental progress to the child’s exposure to the video.

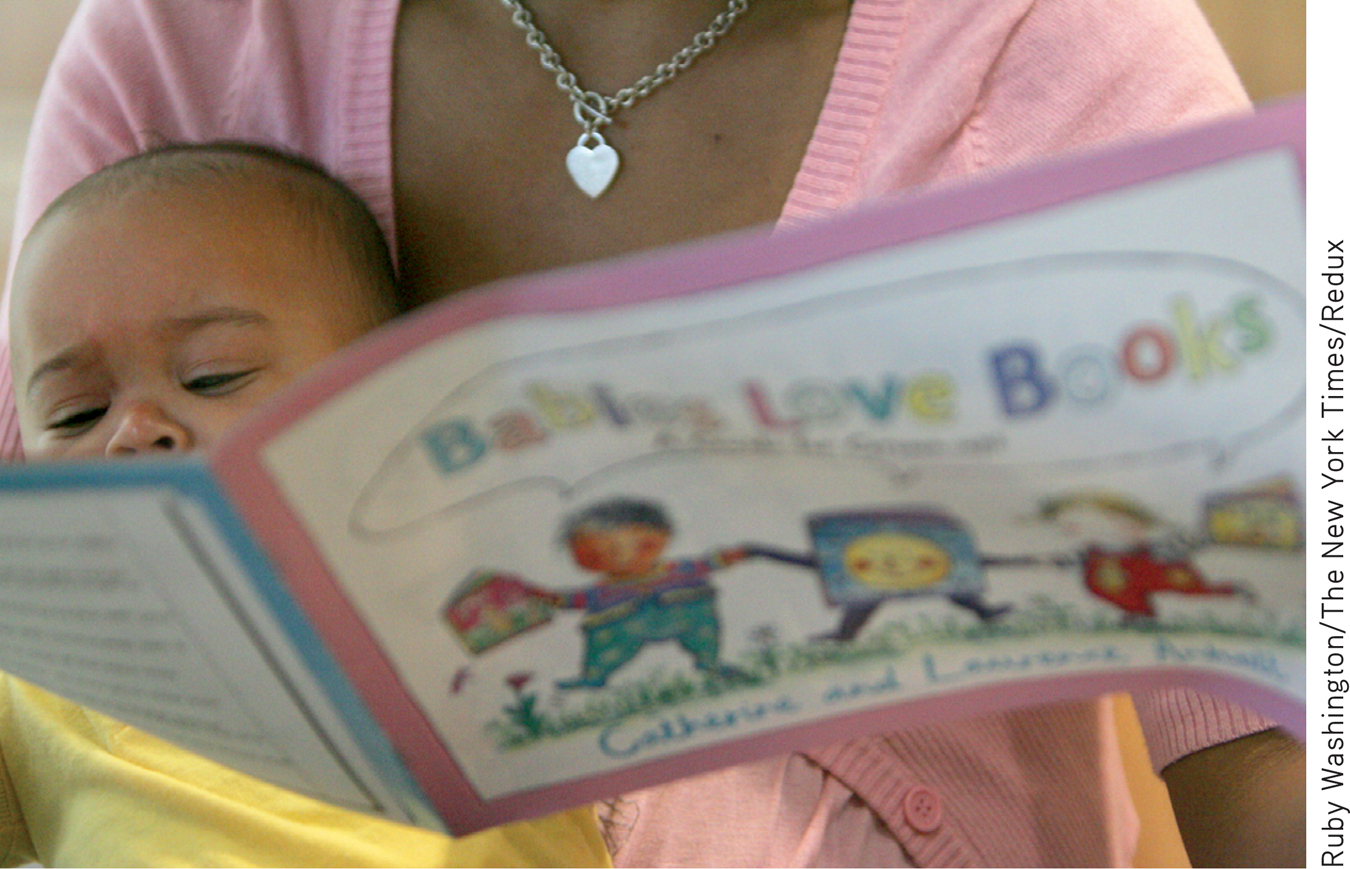

Since the research on baby media began to be published, some companies, like the producers of Baby Einstein, have revised their marketing materials to emphasize the “engaging” nature of the media rather than its “educational” nature. The research is clear: Interacting with a parent or other caregiver is by far the most effective way to increase an infant’s cognitive and, especially, language skills.

The bottom line: Save your money and talk to your baby. Better yet, read to him! Several studies have found that the best predictor of infant language is the amount of time that parents spend reading to their children (Robb & others, 2009).

THE TWO-WORD STAGE OF LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT

Around their second birthday, toddlers begin putting words together. During the two-word stage, they combine two words to construct a simple “sentence,” such as “Mama go,” “Where kitty?” and “No potty!” During this stage, the words used are primarily content words—nouns, verbs, and sometimes adjectives or adverbs. Articles (a, an, the) and prepositions (such as in, under, on) are omitted. Two-word sentences reflect the first understandings of grammar. Although these utterances include only the most essential words, they basically follow a grammatically correct sequence.

At around 2-1/2 years of age, children move beyond the two-word stage. They rapidly increase the length and grammatical complexity of their sentences. There is a dramatic increase in the number of words they can comprehend and produce. By the age of 3, the typical child has a production vocabulary of more than 3,000 words. Acquiring about a dozen new words per day, a child may have a production vocabulary of more than 10,000 words by school age (Bjorklund, 1995).

Many new parents, eager to accelerate their young children’s language and cognitive development, purchase DVDs or videos that claim to educate as well as entertain the growing child. But what do babies learn from baby videos? We take a critical look at this question in the Science Versus Pseudoscience box, “Can a DVD Program Your Baby to Be a Genius?”

CONCEPT REVIEW 9.1

Early Development

Indicate whether each of the following statements is true or false.

Question 9.1

1. Each chromosome has exactly 23 genes.

| A. |

| B. |

Question 9.2

2. Different types of body cells develop because they have a different combination of genes in their cell nucleus.

| A. |

| B. |

Question 9.3

3. The greatest vulnerability to teratogens usually occurs during the embryonic stage.

| A. |

| B. |

Question 9.4

4. At birth, the brain is fully developed and no longer has the capacity to generate new neurons or dendrites.

| A. |

| B. |

Question 9.5

5. Vision is the least well-developed sense in the human newborn.

| A. |

| B. |

Question 9.6

6. Sam, who is 4 years old, adapts easily to new situations. Sam would probably be classified as “slow-to-warm-up” in temperament.

| A. |

| B. |

Question 9.7

7. Instead of happily exploring the toys in the doctor’s waiting room, Amy clings to her mother’s hand, a behavior that characterizes an insecurely attached toddler.

| A. |

| B. |

Question 9.8

8. Infants babble using only the sounds that they hear in their home environment.

| A. |

| B. |

Cognitive Development

KEY THEME

According to Piaget’s theory, children progress through four distinct cognitive stages, and each stage marks a shift in how they think and understand the world.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are Piaget’s four stages of cognitive development?

What are three criticisms of Piaget’s theory?

How do Vygotsky’s ideas about cognitive development differ from Piaget’s theory?

Just as children advance in motor skill and language development, they also develop increasing sophistication in cognitive processes—thinking, remembering, and processing information. The most influential theory of cognitive development is that of Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget. Originally trained as a biologist, Piaget (1961) combined a boundless curiosity about the nature of the human mind with a gift for scientific observation (Boeree, 2006).

Piaget (1952, 1972) believed that children actively try to make sense of their environment rather than passively soaking up information about the world. To Piaget, many of the “cute” things children say actually reflect their sincere attempts to make sense of their world. In fact, Piaget carefully observed his own three children in developing his theory and published three books about them (Boeree, 2006).

According to Piaget, children progress through four distinct cognitive stages: the sensorimotor stage, from birth to age 2; the preoperational stage, from age 2 to age 7; the concrete operational stage, from age 7 to age 11; and the formal operational stage, which begins during adolescence and continues into adulthood. As a child advances to a new stage, his thinking is qualitatively different from that of the previous stage. In other words, each new stage represents a fundamental shift in how the child thinks and understands the world.

Piaget saw this progression of cognitive development as a continuous, gradual process. As a child develops and matures, she does not simply acquire more information. Rather, she develops a new understanding of the world in each progressive stage, building on the understandings acquired in the previous stage (Piaget, 1961). As the child assimilates new information and experiences, she eventually changes her way of thinking to accommodate new knowledge (Piaget, 1961).

Piaget (1971) believed that these stages were biologically programmed to unfold at their respective ages. He also believed that children in every culture progressed through the same sequence of stages at roughly similar ages. However, Piaget also recognized that hereditary and environmental differences could influence the rate at which a given child progressed through the stages.

For example, a “bright” child may progress through the stages faster than a child who is less intellectually capable. A child whose environment provides ample and varied opportunities for exploration is likely to progress faster than a child who has limited environmental opportunities. Thus, even though the sequence of stages is universal, there can be individual variation in the rate of cognitive development.

THE SENSORIMOTOR STAGE

The sensorimotor stage extends from birth until about 2 years of age. During this stage, infants acquire knowledge about the world through actions that allow them to directly experience and manipulate objects. Infants discover a wealth of very practical sensory knowledge, such as what objects look like and how they taste, feel, smell, and sound.

sensorimotor stage

In Piaget’s theory, the first stage of cognitive development, from birth to about age 2; the period during which the infant explores the environment and acquires knowledge through sensing and manipulating objects.

Infants in this stage also expand their practical knowledge about motor actions—reaching, grasping, pushing, pulling, and pouring. In the process, they gain a basic understanding of the effects their own actions can produce, such as pushing a button to turn on the television or knocking over a pile of blocks to make them crash and tumble.

At the beginning of the sensorimotor stage, the infant’s motto seems to be “Out of sight, out of mind.” An object exists only if she can directly sense it. For example, if a 4-month-old infant knocks a ball underneath the couch and it rolls out of sight, she will not look for it. Piaget interpreted this response to mean that to the infant, the ball no longer exists.

However, by the end of the sensorimotor stage, children acquire a new cognitive understanding, called object permanence. Object permanence is the understanding that an object continues to exist even if it can’t be seen. Now the infant will actively search for a ball that she has watched roll out of sight (Mash & others, 2006). Infants gradually acquire an understanding of object permanence as they gain experience with objects, as their memory abilities improve, and as they develop mental representations of the world, which Piaget called schemas (Perry & others, 2008).

object permanence

The understanding that an object continues to exist even when it can no longer be seen.

THE PREOPERATIONAL STAGE

The preoperational stage lasts from roughly age 2 to age 7. In Piaget’s theory, the word operations refers to logical mental activities. Thus, the “preoperational” stage is a prelogical stage.

preoperational stage

In Piaget’s theory, the second stage of cognitive development, which lasts from about age 2 to age 7; characterized by increasing use of symbols and prelogical thought processes.

The hallmark of preoperational thought is the child’s capacity to engage in symbolic thought. Symbolic thought refers to the ability to use words, images, and symbols to represent the world. One indication of the expanding capacity for symbolic thought is the child’s impressive gains in language during this stage.

symbolic thought

The ability to use words, images, and symbols to represent the world.

The child’s increasing capacity for symbolic thought is also apparent in her use of fantasy and imagination while playing. A discarded box becomes a spaceship, a house, or a fort as children imaginatively take on the roles of different characters. Some children even create an imaginary companion (Taylor & others, 2009).

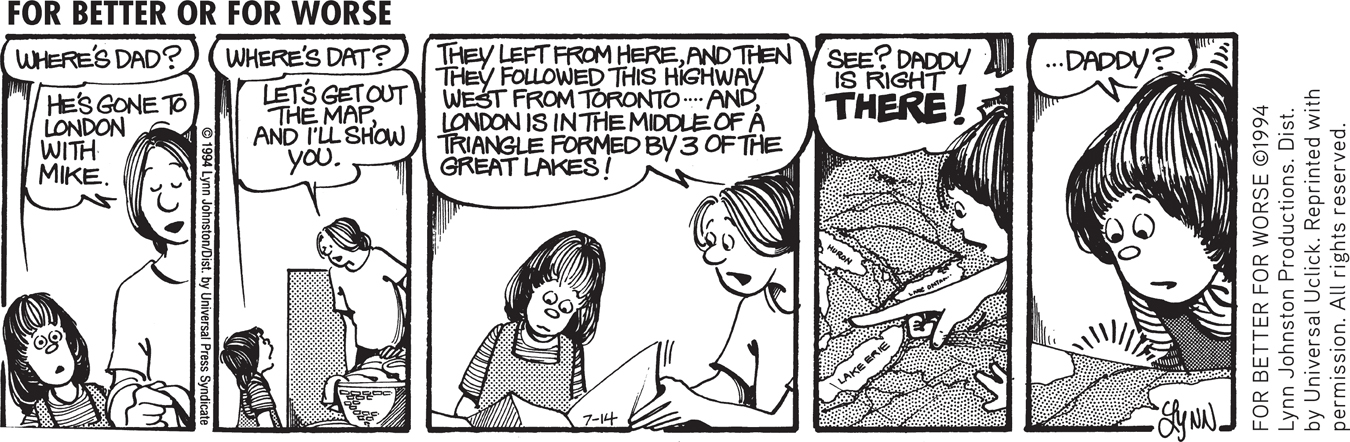

Still, the preoperational child’s understanding of symbols remains immature. A 2-year-old shown a picture of a flower, for example, may try to smell it. A young child may be puzzled by the notion that a map symbolizes an actual location—as in the cartoon above. In short, preoperational children are still actively figuring out the relationship between symbols and the actual objects they represent.

The thinking of preoperational children often displays egocentrism. By egocentrism, Piaget did not mean selfishness or conceit. Rather, egocentric children lack the ability to consider events from another person’s point of view. Thus, the young child genuinely thinks that Grandma would like a new Lego set or video game for her upcoming birthday because that’s what he wants. Egocentric thought is also operating when the child silently nods his head in answer to Grandpa’s question on the telephone.

egocentrism

In Piaget’s theory, the inability to take another person’s perspective or point of view.

The preoperational child’s thought is also characterized by irreversibility and centration. Irreversibility means that the child cannot mentally reverse a sequence of events or logical operations back to the starting point. For example, the child doesn’t understand that adding “3 plus 1” and adding “1 plus 3” refer to the same logical operation. Centration refers to the tendency to focus, or center, on only one aspect of a situation, usually a perceptual aspect. In doing so, the child ignores other relevant aspects of the situation.

irreversibility

In Piaget’s theory, the inability to mentally reverse a sequence of events or logical operations.

centration

In Piaget’s theory, the tendency to focus, or center, on only one aspect of a situation and ignore other important aspects of the situation.

When Laura was almost 3, Sandy and Laura were investigating the tadpoles in the creek behind our home. “Do you know what tadpoles become when they grow up? They become frogs,” Sandy explained. Laura looked very serious. After considering this new bit of information for a few moments, she asked, “Laura grow up to be a frog, too?”

The classic demonstration of both irreversibility and centration involves a task devised by Piaget. When Sandy and Don’s daughter Laura was 5, they tried this task with her. First, they showed her two identical glasses, each containing exactly the same amount of liquid. Laura easily recognized the two amounts of liquid as being the same.

Then, while Laura watched intently, Sandy poured the liquid from one of the glasses into a third container that was much taller and narrower than the others. “Which container,” Sandy asked, “holds more liquid?” Like any other preoperational child, Laura answered confidently, “The taller one!” Even when the procedure was repeated, reversing the steps over and over again, Laura remained convinced that the taller container held more liquid than did the shorter container.

This classic demonstration illustrates the preoperational child’s inability to understand conservation. The principle of conservation holds that two equal physical quantities remain equal even if the appearance of one is changed, as long as nothing is added or subtracted (Piaget & Inhelder, 1974). Because of centration, the child cannot simultaneously consider the height and the width of the liquid in the container. Instead, the child focuses on only one aspect of the situation, the height of the liquid. And because of irreversibility, the child cannot cognitively reverse the series of events, mentally returning the poured liquid to its original container. Thus, she fails to understand that the two amounts of liquid are still the same.

conservation

In Piaget’s theory, the understanding that two equal quantities remain equal even though the form or appearance is rearranged, as long as nothing is added or subtracted.

Think Like a SCIENTIST

Children’s cognition is also affected by environmental factors. For example, what classroom decor better helps kindergarten students learn? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about Learning Environments.

THE CONCRETE OPERATIONAL STAGE

With the beginning of the concrete operational stage, at around age 7, children become capable of true logical thought. They are much less egocentric in their thinking, can reverse mental operations, and can focus simultaneously on two aspects of a problem. In short, they understand the principle of conservation. When presented with two rows of pennies, each row equally spaced, concrete operational children understand that the number of pennies in each row remains the same even when the spacing between the pennies in one row is increased.

concrete operational stage

In Piaget’s theory, the third stage of cognitive development, which lasts from about age 7 to adolescence; characterized by the ability to think logically about concrete objects and situations.

As the name of this stage implies, thinking and use of logic tend to be limited to concrete reality—to tangible objects and events. Children in the concrete operational stage often have difficulty thinking logically about hypothetical situations or abstract ideas. For example, an 8-year-old will explain the concept of friendship in very tangible terms, such as “Friendship is when someone plays with me.” In effect, the concrete operational child’s ability to deal with abstract ideas and hypothetical situations is limited to his or her personal experiences and actual events.

THE FORMAL OPERATIONAL STAGE

At the beginning of adolescence, children enter the formal operational stage. In terms of problem solving, the formal operational adolescent is much more systematic and logical than the concrete operational child (Kuhn & Franklin, 2006). Formal operational thought reflects the ability to think logically even when dealing with abstract concepts or hypothetical situations (Kuhn, 2008; Piaget, 1972; Piaget & Inhelder, 1958). In contrast to the concrete operational child, the formal operational adolescent explains friendship by emphasizing more global and abstract characteristics, such as mutual trust, empathy, loyalty, consistency, and shared beliefs (Harter, 1990).

formal operational stage

In Piaget’s theory, the fourth stage of cognitive development, which lasts from adolescence through adulthood; characterized by the ability to think logically about abstract principles and hypothetical situations.

But, like the development of cognitive abilities during infancy and childhood, formal operational thought emerges only gradually. Formal operational thought continues to increase in sophistication throughout adolescence and adulthood. Although an adolescent may deal effectively with abstract ideas in one domain of knowledge, his thinking may not reflect the same degree of sophistication in other areas. Piaget (1973) acknowledged that even among many adults, formal operational thinking is often limited to areas in which they have developed expertise or a special interest. TABLE 9.2 summarizes Piaget’s stages of cognitive development.

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development

| Stage | Characteristics of the Stage | Major Change of the Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Sensorimotor (0– |

Acquires understanding of object permanence. First understandings of cause-and-effect relationships. | Development proceeds from reflexes to active use of sensory and motor skills to explore the environment. |

| Preoperational (2– |

Symbolic thought emerges. Language development occurs (2– |

Development proceeds from understanding simple cause-and-effect relationships to prelogical thought processes involving the use of imagination and symbols to represent objects, actions, and situations. |

| Concrete operations (7– |

Reversibility attained. Can solve conservation problems. Logical thought develops and is applied to concrete problems. Cannot solve complex verbal problems and hypothetical problems. | Development proceeds from prelogical thought to logical solutions to concrete problems. |

| Formal operations (adolescence through adulthood) | Logically solves all types of problems. Thinks scientifically. Solves complex verbal and hypothetical problems. Is able to think in abstract terms. | Development proceeds from logical solving of concrete problems to logical solving of all classes of problems, including abstract problems. |

!launch!

CRITICISMS OF PIAGET’S THEORY

Piaget’s theory has inspired hundreds, if not thousands, of research studies, and he is considered one of the most important scientists of the twentieth century (Perret-Clermont & Barrelet, 2008). Generally, scientific research has supported Piaget’s most fundamental idea: that infants, young children, and older children use distinctly different cognitive abilities to construct their understanding of the world. However, other aspects of Piaget’s theory have been challenged.

Criticism 1: Piaget underestimated the cognitive abilities of infants and young children.To test for object permanence, Piaget would show an infant an object, cover it with a cloth, and then observe whether the infant tried to reach under the cloth for the object. Using this procedure, Piaget found that it wasn’t until an infant was about 9 months old that she behaved as if the object continued to exist after it was hidden.

But what if the infant “knew” that the object was under the cloth but simply lacked the physical coordination to reach for it? How could you test this hypothesis? Rather than using manual tasks to assess object permanence and other cognitive abilities, Renée Baillargeon developed a method based on visual tasks. Baillargeon’s research is based on the premise that infants, like adults, will look longer at “surprising” events that appear to contradict their understanding of the world (Baillargeon & others, 2011, 2012).

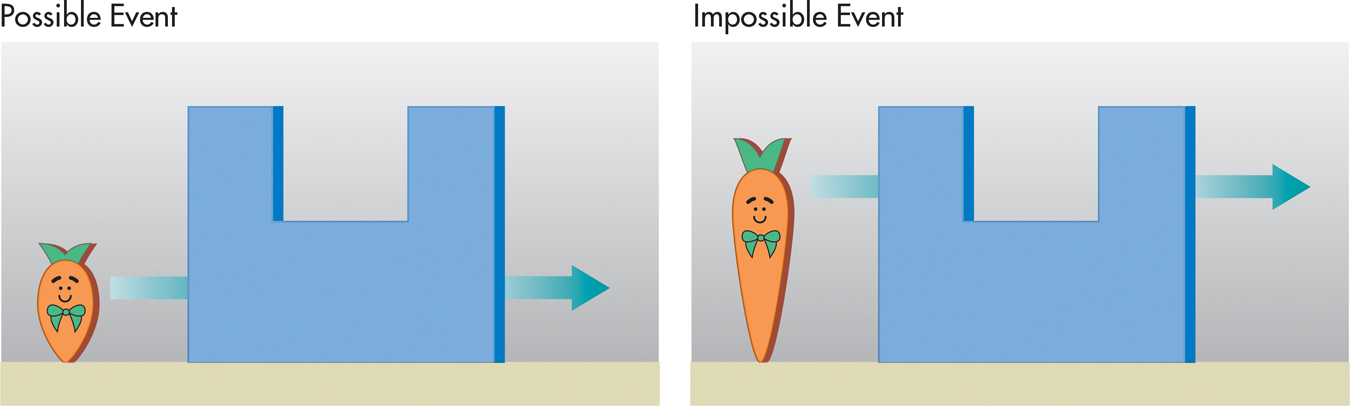

In this research paradigm, the infant first watches an expected event, which is consistent with the understanding that is being tested. Then, the infant is shown an unexpected event. If the unexpected event violates the infant’s understanding of physical principles, he should be surprised and look longer at the unexpected event than the expected event.

FIGURE 9.4 shows one of Baillargeon’s classic tests of object permanence, conducted with Julie DeVos (Baillargeon & DeVos, 1991). If the infant understands that objects continue to exist even when they are hidden, she will be surprised when the tall carrot unexpectedly does not appear in the window of the panel.

Using variations of this basic experimental procedure, Baillargeon and her colleagues have shown that infants as young as 2 1/2 months of age display object permanence (Baillargeon & others, 2009; Luo & others, 2009). This is more than six months earlier than the age at which Piaget believed infants first showed evidence of object permanence.

Piaget’s discoveries laid the groundwork for our understanding of cognitive development. However, as developmental psychologists Jeanne Shinskey and Yuko Munakata (2005) observe, today’s researchers recognize that “what infants appear to know depends heavily on how they are tested.”

Criticism 2: Piaget underestimated the impact of the social and cultural environment on cognitive development.In contrast to Piaget, the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky believed that cognitive development is strongly influenced by social and cultural factors. Vygotsky formulated his theory of cognitive development at about the same time Piaget formulated his. However, Vygotsky’s writings did not become available in the West until many years after his untimely death from tuberculosis in 1934 (Rowe & Wertsch, 2002; van Geert, 1998).

Vygotsky agreed with Piaget that children may be able to reach a particular cognitive level through their own efforts. However, Vygotsky (1978, 1987) argued that children are able to attain higher levels of cognitive development through the support and instruction that they receive from other people. Researchers have confirmed that social interactions, especially with older children and adults, play a significant role in a child’s cognitive development (Psaltis & others, 2009; Wertsch, 2008).

One of Vygotsky’s important ideas was his notion of the zone of proximal development. This refers to the gap between what children can accomplish on their own and what they can accomplish with the help of others who are more competent (Holzman, 2009). Note that the word proximal means “nearby,” indicating that the assistance provided goes just slightly beyond the child’s current abilities. Such guidance can help “stretch” the child’s cognitive abilities to new levels.

zone of proximal development

In Vygotsky’s theory of cognitive development, the difference between what children can accomplish on their own and what they can accomplish with the help of others who are more competent.

Cross-cultural studies have shown that cognitive development is strongly influenced by the skills that are valued and encouraged in a particular environment, such as the ability to weave, hunt, or collaborate with others (Greenfield, 2009; Wells, 2009). Such findings suggest that Piaget’s stages are not as universal and culture-free as some researchers had once believed (Cole & Packer, 2011).

Criticism 3: Piaget overestimated the degree to which people achieve formal operational thought processes.Researchers have found that many adults display abstract-hypothetical thinking only in limited areas of knowledge, and that some adults never display formal operational thought processes at all (see Kuhn, 2008; Molitor & Hsu, 2011). College students, for example, may not display formal operational thinking when given problems outside their major, as when an English major is presented with a physics problem (DeLisi & Staudt, 1980). Late in his life, Piaget (1972, 1973) suggested that formal operational thinking might not be a universal phenomenon but, instead, is the product of an individual’s expertise in a specific area.

Rather than distinct stages of cognitive development, some developmental psychologists emphasize the information-processing model of cognitive development. This model focuses on the development of fundamental mental processes, such as attention, memory, and problem solving (Munakata & others, 2006). In this approach, cognitive development is viewed as a process of continuous change over the lifespan (Courage & Howe, 2002; Craik & Bialystok, 2006). Through life experiences, we continue to acquire new knowledge, including more sophisticated cognitive skills and strategies. In turn, this improves our ability to process, learn, and remember information.

information-processing model of cognitive development

The model that views cognitive development as a process that is continuous over the lifespan and that studies the development of basic mental processes such as attention, memory, and problem solving.

With the exceptions that have been noted, Piaget’s observations of the changes in children’s cognitive abilities are fundamentally accurate. His description of the distinct cognitive changes that occur during infancy and childhood ranks as one of the most outstanding contributions to developmental psychology.

CONCEPT REVIEW 9.2

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development

Indicate which stage of cognitive development is illustrated by each of the following examples.

Question

formal operational preoperational sensorimotor concrete operational | When confronted with a lawn mower that will not start, Jason approaches the problem very systematically, checking and eliminating possible causes one at a time. When Carla’s mother hides her favorite toy under a cushion, Carla starts playing with another toy and acts as though her favorite toy no longer exists. Andrew is told that Michael is taller than Bridget and Bridget is taller than Patrick. When asked who is the shortest child, Andrew thinks carefully and then answers, “Patrick.” Lynn rolls identical amounts of clay into two balls and is quite sure they are exactly the same. However, when her dad flattens one ball into a pancake shape, Lynn is confident that the pancake has more clay than the ball. |

Test your understanding of Infancy and Childhood with

.

.