9.5 Adolescence

KEY THEME

Adolescence is the stage that marks the transition from childhood to adulthood.

KEY QUESTIONS

What factors affect the timing of puberty?

What characterizes adolescent relationships with parents and peers?

What is Erikson’s psychosocial theory of lifespan development?

Adolescence is the transitional stage between late childhood and the beginning of adulthood. Although it can vary by individual, culture, and gender, adolescence usually begins around age 11 or 12. It is a transition marked by sweeping physical, social, and cognitive changes as the individual moves toward independence and adult responsibilities. Outwardly, the most noticeable changes that occur during adolescence are the physical changes that accompany the development of sexual maturity. We’ll begin by considering those changes, then turn to the aspects of social development during adolescence. Following that discussion, we’ll consider some of the cognitive changes of adolescence, including identity formation.

adolescence

The transitional stage between late childhood and the beginning of adulthood, during which sexual maturity is reached.

Physical and Sexual Development

Nature seems to have a warped sense of humor when it comes to puberty, the physical process of attaining sexual maturation and reproductive capacity that begins during the early adolescent years. As you may well remember, physical development during adolescence sometimes proceeds unevenly. Feet and hands get bigger before legs and arms do. The torso typically develops last, so shirts and blouses sometimes don’t fit quite right. And the left and right sides of the body can grow at different rates. The resulting lopsided effect can be quite distressing: One ear, foot, testicle, or breast may be noticeably larger than the other. Thankfully, such asymmetries tend to even out by the end of adolescence.

puberty

The stage of adolescence in which an individual reaches sexual maturity and becomes physiologically capable of sexual reproduction.

Although nature’s game plan for physical change during adolescence may seem haphazard, puberty actually tends to follow a predictable sequence for each sex. These changes are summarized in TABLE 9.3.

The Typical Sequence of Puberty

| Girls | Average Age | Boys | Average Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ovaries increase production of estrogen and progesterone. | 9 | Testes increase production of testosterone. | 10 |

| Internal sex organs begin to grow larger. | 9 1/2 | External sex organs begin to grow larger. | 11 |

| Breast development begins. | 10 | Production of sperm and first ejaculation | 13 |

| Peak height spurt | 12 | Peak height spurt | 14 |

| Peak muscle and organ growth, including widening of hips | 12 1/2 | Peak muscle and organ growth, including broadening of shoulders | 14 1/2 |

| Menarche (first menstrual period) | 12 1/2 | Voice lowers. | 15 |

| First ovulation (release of fertile egg) | 13 1/2 | Facial hair appears. | 16 |

| Source: Data from Brooks-Gunn & Reiter (1990). | |||

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SEX CHARACTERISTICS

The physical changes of puberty fall into two categories. Internally, puberty involves the development of the primary sex characteristics, which are the sex organs that are directly involved in reproduction. For example, the female’s uterus and the male’s testes enlarge in puberty. Externally, development of the secondary sex characteristics, which are not directly involved in reproduction, signals increasing sexual maturity. Secondary sex characteristics include changes in height, weight, and body shape; the appearance of body hair and voice changes; and, in girls, breast development.

primary sex characteristics

Sexual organs that are directly involved in reproduction, such as the uterus, ovaries, penis, and testicles.

secondary sex characteristics

Sexual characteristics that develop during puberty and are not directly involved in reproduction but differentiate between the sexes, such as male facial hair and female breast development.

As you can see in TABLE 9.3, females are typically about two years ahead of males in terms of physical and sexual maturation. For example, the period of marked acceleration in weight and height gains, called the adolescent growth spurt, occurs about two years earlier in females than in males. Much to the chagrin of many sixth and seventh-grade boys, it’s not uncommon for their female classmates to be both heavier and taller than they are.

adolescent growth spurt

The period of accelerated growth during puberty, involving rapid increases in height and weight.

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

The Adolescent Brain: A Work in Progress

For many adolescents, the teenage years, especially the early ones, seem to seesaw between moments of exhilaration and exasperation. Impressive instances of insightful behavior are counterbalanced by impulsive decisions made with no consideration of the potential risks or consequences. Many psychologists believe that an important factor in explaining erratic and risky behavior involves the still-developing adolescent brain.

To track changes in the developing brain, neuroscientists Jay Giedd, Elizabeth Sowell, Paul Thompson, and their colleagues have used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to repeatedly scan the brains of normal kids and teenagers. One striking insight produced by their studies is that the human brain goes through not one but two distinct spurts of brain development—one during prenatal development and one during late childhood just prior to puberty (Giedd, 2008; Gogtay & others, 2004; Lenroot & Giedd, 2006).

Earlier in the chapter, we described how new neurons are produced at an astonishing rate during the first months of prenatal development. By the sixth month of prenatal development, there is a vast overabundance of neurons in the fetal brain. During the final months of prenatal development, neurons that don’t make connections are “pruned” or eliminated. During infancy and early childhood, the brain’s outer gray matter continues to develop and grow. The tapestry of interconnections between neurons becomes much more intricate as dendrites and axon terminals multiply and branch to extend their reach. White matter also increases as groups of neurons develop myelin, the white, fatty covering that insulates some axons, speeding communication between neurons.

Outwardly, these brain changes are reflected in the increasing cognitive and physical capabilities of the child. But in the brain itself, the “use-it-or-lose-it” principle is at work: Unused neuron circuits are being pruned. While it may seem counterintuitive, the loss of unused neurons and neuronal connections actually improves brain functioning by making the remaining neurons more efficient in processing information.

By 6 years of age, the child’s brain is about 95 percent of its adult size. The longitudinal MRI studies of normal kids and adolescents revealed that a second wave of gray matter overproduction occurred just prior to puberty. This late childhood surge of cortical gray matter is not due to the production of new neurons. Rather, the size, complexity, and connections among neurons all increase. This increase in gray matter peaks at about age 11 for girls and age 12 for boys (Toga & others, 2006). And this surge is followed by a second round of neuronal pruning during the teenage years (Giedd & others, 2009; Toga & others, 2006).

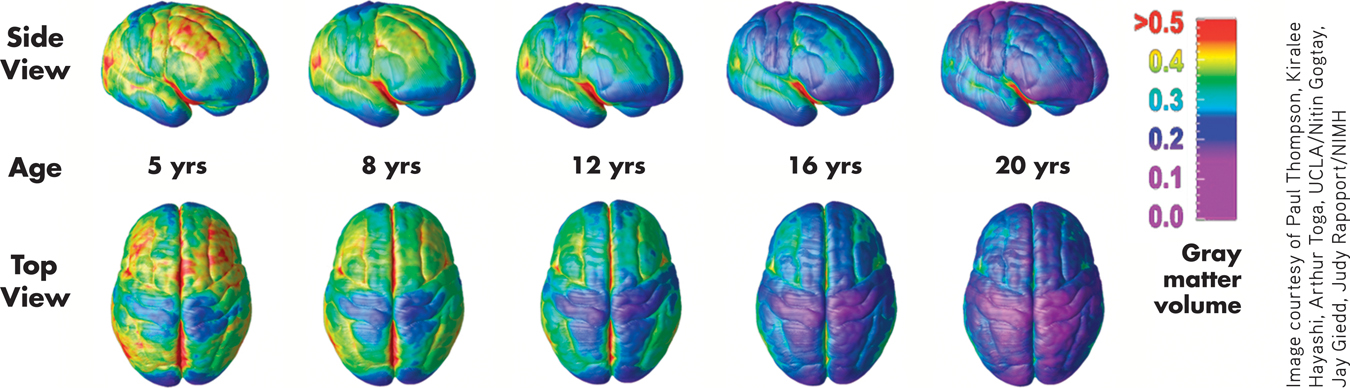

Pruning Gray Matter from Back to Front

The color-coded series of brain images below shows the course of brain development from ages 5 to 20 (Gogtay & others, 2004). Red indicates more gray matter; blue indicates less gray matter.

The MRI images reveal that as the brain matures, neuronal connections are pruned and gray matter diminishes in a back-to-front wave. As pruning occurs, the connections that remain are strengthened and reinforced, and the amount of white matter in the brain steadily increases (Giedd, 2009; Schmithorst & Yuan, 2010). More specifically, the first brain areas to mature are at the extreme front and back of the brain. These areas are involved with very basic functions, such as processing sensations and movement. The next brain areas to mature are the parietal lobes, which are involved in language and spatial skills.

The last brain area to experience pruning and maturity is the prefrontal cortex. This is significant because the prefrontal cortex plays a critical role in many advanced or “executive” cognitive functions, such as a person’s ability to reason, plan, organize, solve problems, and decide. And when does the prefrontal cortex reach full maturity? According to the MRI studies, not until people reach their mid-20s (Gogtay & others, 2004).

This suggests that an adolescent’s occasional impulsive or immature behavior is at least partly a reflection of a brain that still has a long way to go to reach full adult maturity (Casey, 2013; Casey & Caudle, 2013). During adolescence, emotions and impulses can be intense and compelling. But the parts of the brain that are responsible for exercising judgment are still maturing (Luna & others, 2013). The result can be behavior that is immature, impulsive, unpredictable—and often risky.

The statistical averages in TABLE 9.3 are informative, but—because they are only averages—they cannot convey the normal range of individual variation in the timing of pubertal events (see Ellis, 2004). For example, a female’s first menstrual period, termed menarche, typically occurs around age 12 or 13, but menarche may take place as early as age 9 or 10 or as late as age 16 or 17. For boys, the testicles typically begin enlarging around age 11 or 12, but the process can begin before age 9 or after age 14.

menarche

(meh-NAR-kee) A female’s first menstrual period, which occurs during puberty.

Thus, it’s entirely possible for some adolescents to have already completed physical and sexual maturation before their classmates have even begun puberty. Yet they would all be considered well within the normal age range for puberty (Sun & others, 2002).

Less obvious than the outward changes associated with puberty are the sweeping changes occurring in another realm of physical development: the adolescent’s brain. We discuss these developments in the Focus on Neuroscience above.

FACTORS AFFECTING THE TIMING OF PUBERTY

Although you might be tempted to think that the onset of puberty is strictly a matter of biological programming, researchers have found that both genetics and environmental factors play a role in the timing of puberty. Genetic evidence includes the observation that girls usually experience menarche at about the same age their mothers did (Ersoy & others, 2005). And, not surprisingly, the timing of pubertal changes tends to be closer for identical twins than for nontwin siblings (Mustanski & others, 2004).

Environmental factors, such as nutrition and health, also influence the onset of puberty. Generally, well-nourished and healthy children begin puberty earlier than do children who have experienced serious health problems or inadequate nutrition. As living standards and health care have improved, the average age of puberty has steadily been decreasing in many countries over the past century.

For example, 150 years ago the average age of menarche in the United States and other developed countries was about 17 years old. Today it is about 13 years old. Boys, too, are beginning the physical changes of puberty about a year earlier today than they did in the 1960s (Irwin, 2005).

Body size and degree of physical activity are also related to the timing of puberty (Aksglaede & others, 2009). In general, heavier children begin puberty earlier than do lean children. Girls who are involved in physically demanding athletic activities, such as gymnastics, figure skating, dancing, and competitive running, can experience delays in menarche of up to two years beyond the average age (Brooks-Gunn, 1988; Georgopoulos & others, 2004).

Interestingly, the timing of puberty is also influenced by the absence of the biological father in the home. Several studies have found that girls raised in homes in which the biological father is absent tend to experience puberty earlier than girls raised in homes where the father is present (Bogaert, 2005a, 2008; Neberich & others, 2010). In another large study, both boys and girls experienced accelerated physical development in homes where fathers were absent (Mustanski & others, 2004).

Why would the absence of a father affect the timing of puberty? A stressful home environment may play a role. In families marked by marital conflict and strife, girls enter puberty earlier, regardless of whether the father remains or leaves (Saxbe & Repetti, 2009). In general, negative and stressful family environments are associated with an earlier onset of puberty, while positive family environments are associated with later physical development (Ellis & Essex, 2007). Although the mechanisms are not completely clear, it may be that stressful family events increase many of the same hormones that are involved in triggering puberty.

EFFECTS OF EARLY VERSUS LATE MATURATION

Adolescents tend to be keenly aware of the physical changes they are experiencing as well as of the timing of those changes compared with their peer group. Most adolescents are “on time,” meaning that the maturational changes are occurring at roughly the same time for them as for others in their peer group.

However, some adolescents are “off time,” experiencing maturation noticeably earlier or later than the majority of their peers. Generally speaking, off-time maturation is stressful for both boys and girls, who may experience teasing, social isolation, and exclusion from social activities (Conley & Rudolph, 2009).

Being off-time has different effects for girls and boys. Girls who develop early and boys who develop late are most likely to have problems. For example, early-maturing girls tend to be more likely than late-maturing girls to have negative feelings about their body image and pubertal changes, such as menarche (Ge & others, 2003). Compared to late-maturing girls, early-maturing girls are less likely to have received factual information concerning development. They may also feel embarrassed by unwanted attention from older males (Brooks-Gunn & Reiter, 1990). Early-maturing girls also have higher rates of sexual risk-taking, drug and alcohol use, and delinquent behavior, and are at greater risk for unhealthy weight gain later in life (Adair & Gordon-Larsen, 2001; Belsky & others, 2010).

Early maturation can be advantageous for boys, but it is also associated with risks. Early-maturing boys tend to be popular with their peers. However, although they are more successful in athletics than late-maturing peers, they are also more susceptible to behaviors that put their health at risk, such as steroid use (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2004). Early-maturing boys are also more prone to feelings of depression, problems at school, and engaging in drug or alcohol use (see Ge & others, 2003; Hayatbakhsh & others, 2009).

Social Development

The changes in adolescents’ bodies are accompanied by changes in their social interactions, most notably with parents and peers. Contrary to what many people think, parent–

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that most adolescents have poor relationships with their parents?

Although parents remain influential throughout adolescence, relationships with friends and peers become increasingly important (Albert & others, 2013; Somerville, 2013). Adolescents usually encounter greater diversity among their peers as they make the transitions to middle school and high school. To a much greater degree than during childhood, the adolescent’s social network, social context, and community influence his or her values, norms, and expectations.

Susceptibility to peer influence peaks during early adolescence (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011). As they grow older, adolescents develop resilience against peer influences and increasingly rely on parents’ influences regarding appropriate behaviors (Cook & others, 2009; Sumter & others, 2009).

Parents often worry that peer influences will lead to undesirable behavior, but researchers have found that peer relationships tend to reinforce the traits and goals that parents fostered during childhood (Steinberg, 2001). This finding is not as surprising as it might seem. Adolescents tend to form friendships with peers who are similar in age, social class, race, and beliefs about drinking, dating, church attendance, and educational goals.

Although peer influence can lead to undesirable behaviors, peers can also influence one another in positive ways (Allen & others, 2008). Friends often exert pressure on one another to study, make good grades, attend college, and engage in prosocial behaviors. This positive influence is especially true for peers who are strong students (Cook & others, 2007).

Romantic and sexual relationships also become increasingly important throughout the adolescent years. One national survey showed that by the age of 12, about one-quarter of adolescents reported having had a “special romantic relationship,” although not necessarily a relationship that included sexual intimacy. By age 15, that percentage increased to 50 percent, and reached 70 percent by the age of 18 (Connolly & McIsaac, 2009).

Social and cultural factors influence when, why, and how adolescents engage in romantic and sexual behaviors. The beginning of dating, for example, coincides more strongly with cultural and social expectations and norms, such as when friends begin to date, than with an adolescent’s degree of physical maturation (see Collins, 2003). In fact, there are stark cultural differences in the age at which adolescents begin to date. For example, 80 percent of Israeli 14-year-olds report some type of dating, as compared to only 50 percent of North Americans of the same age (Connolly & McIsaac, 2009).

The physical and social developments we’ve discussed so far are the more obvious changes associated with the onset of puberty. No less important, however, are the cognitive changes that allow the adolescent to think and reason in new, more complex ways.

Identity Formation

ERIKSON’S THEORY OF PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

When psychologists talk about a person’s identity, they are referring to her sense of self, including her memories, experiences, and the values and beliefs that guide her behavior. Our sense of personal identity gives us an integrated and continuing sense of self over time.

identity

A person’s sense of self, including his or her memories, experiences, and the values and beliefs that guide his or her behavior.

Identity formation is a process that continues throughout the lifespan. As we embrace new and different roles over the course of our lives, we define ourselves in new and different ways (Erikson & others, 1986; McAdams & Olson, 2010).

For the first time in the lifespan, the adolescent possesses the cognitive skills necessary for dealing with identity issues in a meaningful way (Sebastian & others, 2008). Beginning in early adolescence, self-definition shifts. Preadolescent children tend to describe themselves in very concrete social and behavioral terms. An 8-year-old might describe himself by saying, “I play with Mark and I like to ride my bike.” In contrast, adolescents use more abstract self-descriptions that reflect personal attributes, values, beliefs, and goals (Phillips, 2008). Thus, a 14-year-old might say, “I have strong religious beliefs, love animals, and hope to become a veterinarian.”

Some aspects of personal identity involve characteristics over which the adolescent really has no control, such as gender, race, ethnic background, and socioeconomic level. In effect, these identity characteristics are fixed and already internalized by the time an individual reaches the adolescent years.

Beyond such fixed characteristics, the adolescent begins to evaluate herself on several different dimensions. Social acceptance by peers, academic and athletic abilities, work abilities, personal appearance, and romantic appeal are some important aspects of self-definition. Another challenge facing the adolescent is to develop an identity that is independent of her parents while retaining a sense of connection to her family. Thus, the adolescent has not one but several self-concepts that she must integrate into a coherent and unified whole to answer the question “Who am I?”

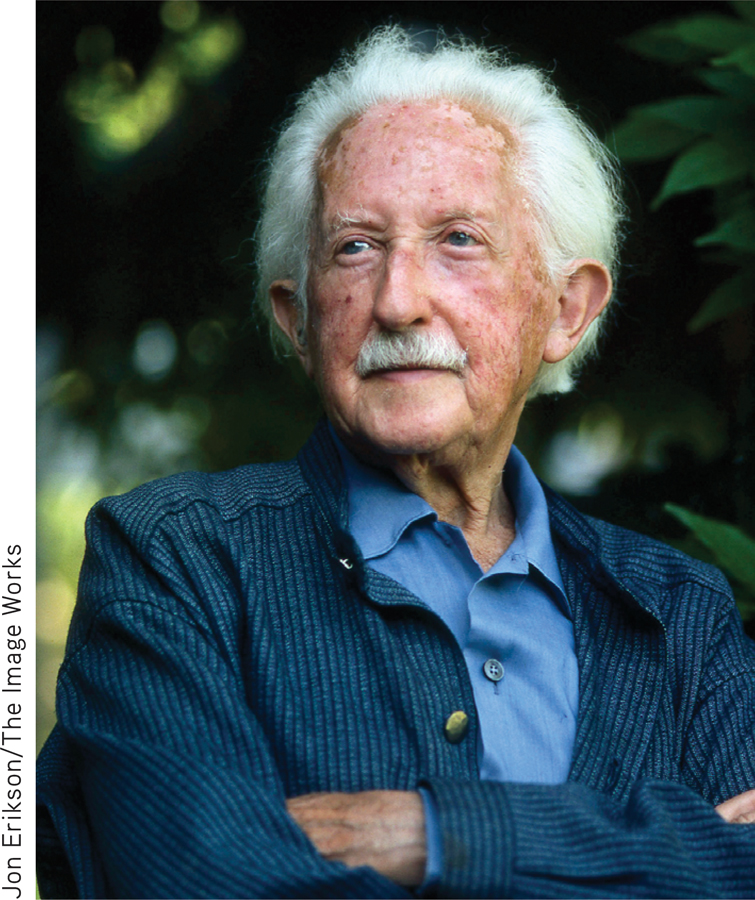

The adolescent’s task of achieving an integrated identity is one important aspect of psychoanalyst Erik Erikson’s influential theory of psychosocial development. Briefly, Erikson (1968) proposed that each of eight stages of life is associated with a particular psychosocial conflict that can be resolved in either a positive or a negative direction (see TABLE 9.4). Relationships with others play an important role in determining the outcome of each conflict. According to Erik-son, the key psychosocial conflict facing adolescents is identity versus role confusion.

Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Stages of Development

| Life Stage | Psychosocial Conflict | Positive Resolution | Negative Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infancy (birth to 18 months) | Trust vs. mistrust | Reliance on consistent and warm caregivers produces a sense of predictability and trust in the environment. | Physical and psychological neglect by caregivers leads to fear, anxiety, and mistrust of the environment. |

| Toddlerhood (18 months to 3 years) | Autonomy vs. doubt | Caregivers encourage independence and self-sufficiency, promoting positive self-esteem. | Overly restrictive caregiving leads to self-doubt in abilities and low self-esteem. |

| Early childhood (3 to 6 years) | Initiative vs. guilt | The child learns to initiate activities and develops a sense of social responsibility concerning the rights of others; promotes self-confidence. | Parental overcontrol stifles the child’s spontaneity, sense of purpose, and social learning; promotes guilt and fear of punishment. |

| Middle and late childhood (6 to 12 years) | Industry vs. inferiority | Through experiences with parents and “keeping up” with peers, the child develops a sense of pride and competence in schoolwork and home and social activities. | Negative experiences with parents or failure to “keep up” with peers leads to pervasive feelings of inferiority and inadequacy. |

| Adolescence | Identity vs. role confusion | Through experimentation with different roles, the adolescent develops an integrated and stable self-definition; forms commitments to future adult roles. | An apathetic adolescent or one who experiences pressures and demands from others may feel confusion about his or her identity and role in society. |

| Young adulthood | Intimacy vs. isolation | By establishing lasting and meaningful relationships, the young adult develops a sense of connectedness and intimacy with others. | Because of fear of rejection or excessive self-preoccupation, the young adult is unable to form close, meaningful relationships and becomes psychologically isolated. |

| Middle adulthood | Generativity vs. stagnation | Through child rearing, caring for others, productive work, and community involvement, the adult expresses unselfish concern for the welfare of the next generation. | Self-indulgence, self-absorption, and a preoccupation with one’s own needs lead to a sense of stagnation, boredom, and a lack of meaningful accomplishments. |

| Late adulthood | Ego integrity vs. despair | In reviewing his or her life, the older adult experiences a strong sense of self-acceptance and meaningfulness in his or her accomplishments. | In looking back on his or her life, the older adult experiences regret, dissatisfaction, and disappointment about his or her life and accomplishments. |

| Source: Research from Erikson (1964a). | |||

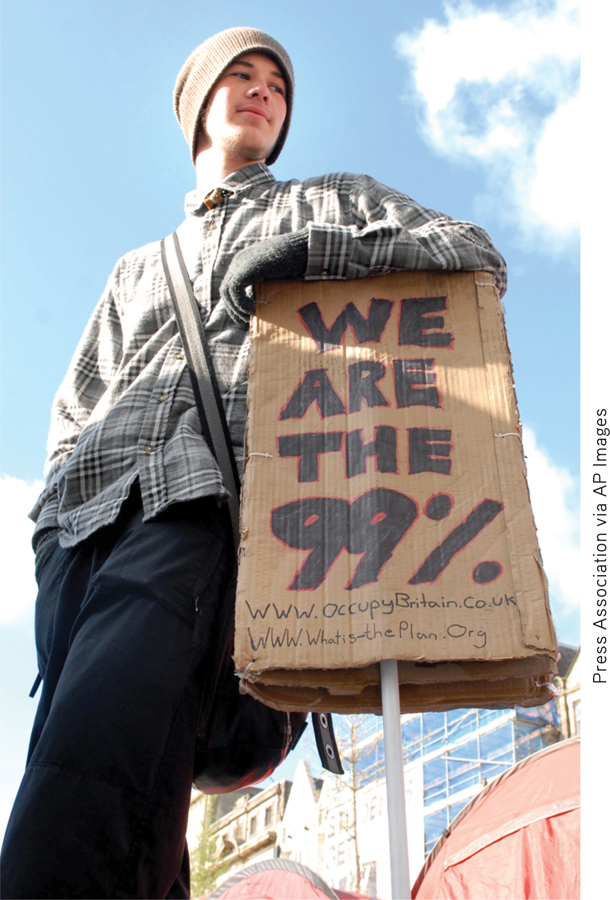

To successfully form an identity, adolescents must not only integrate various dimensions of their personality into a coherent whole but also define the roles that they will adopt within the larger society on becoming an adult (Bohn & Berntsen, 2008). To accomplish this, adolescents grapple with a wide variety of issues, such as selecting a potential career and formulating religious, moral, and political beliefs. They must also adopt social roles involving interpersonal relationships, sexuality, and long-term commitments such as marriage and parenthood.

In Erikson’s (1968) theory, the adolescent’s path to successful identity achievement begins with role confusion, which is characterized by little sense of commitment on any of these issues. This period is followed by a moratorium period, during which the adolescent experiments with different roles, values, and beliefs. Gradually, by choosing among the alternatives and making commitments, the adolescent arrives at an integrated identity.

Psychological research has generally supported Erikson’s description of the process of identity formation (Phillips, 2008). However, it’s important to keep in mind that identity continues to evolve over the entire lifespan, not just during the adolescent years (Whitbourne & others, 2009). Adolescents and young adults seem to achieve a stable sense of identity in some areas earlier than in others. Far fewer adolescents and young adults have attained a stable sense of identity in the realm of religious and political beliefs than in the realm of vocational choice.

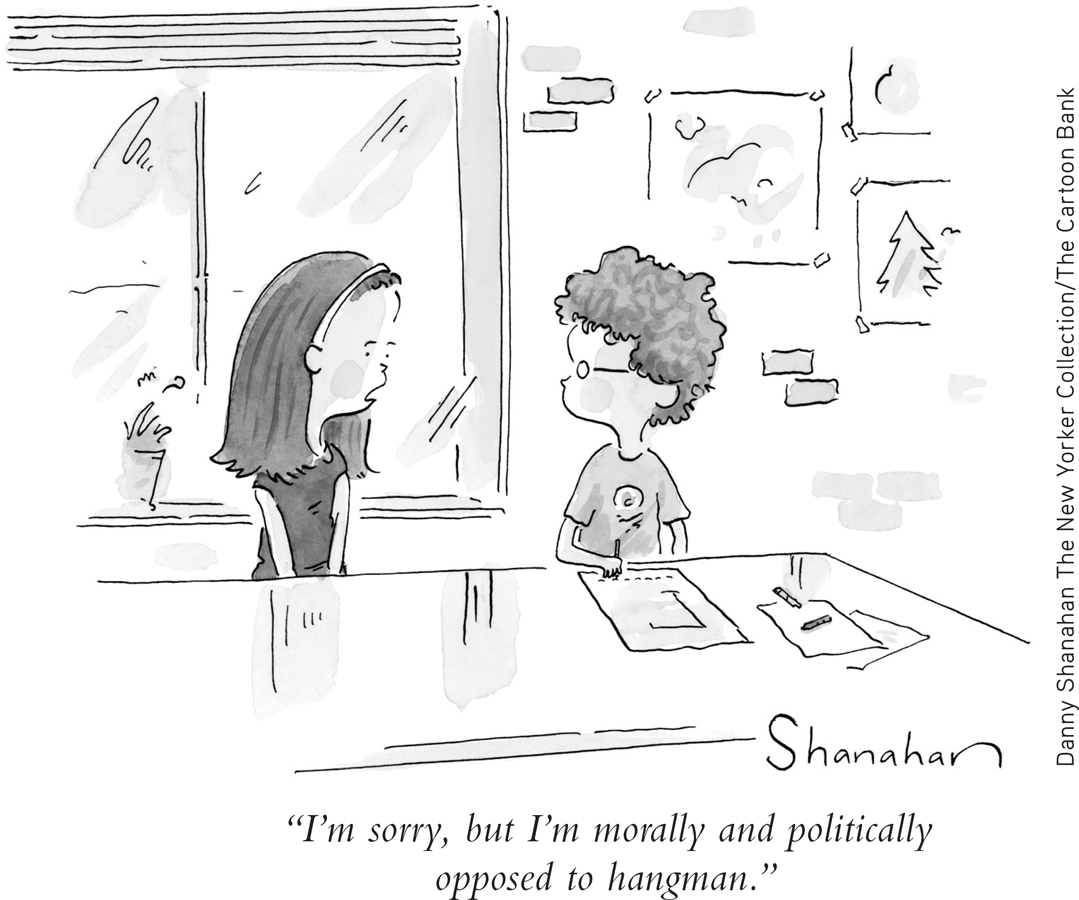

The Development of Moral Reasoning

An important aspect of cognitive development during adolescence is a change in moral reasoning—how an individual thinks about moral and ethical decisions. Adolescents and adults often face moral decisions on difficult interpersonal and social issues (Hart, 2005). What is the right thing to do at a given time and place? How is the best possible outcome achieved for all? The adolescent’s increased capacities to think abstractly, imagine hypothetical situations, and compare ideals to the real world all affect his thinking about moral issues (Fox & Killen, 2008; Kagan & Sinnott-Armstrong, 2008; Turiel, 2010).

moral reasoning

The aspect of cognitive development that has to do with how an individual reasons about moral decisions.

The most influential theory of moral development was proposed by Lawrence Kohlberg (1927–

Kohlberg proposed three distinct levels of moral reasoning: preconventional, conventional, and postconventional. Each level is based on the degree to which a person conforms to conventional standards of society. Furthermore, each level has two stages that represent different degrees of sophistication in moral reasoning. TABLE 9.5 describes the characteristics of the moral reasoning associated with each of Kohlberg’s levels and stages.

Kohlberg’s Levels and Stages of Moral Development

| I. | Preconventional Level |

| Moral reasoning is guided by external consequences. No internalization of values or rules. Stage 1: Punishment and Obedience “Right” is obeying the rules simply to avoid punishment because others have power over you and can punish you. Stage 2: Mutual Benefit “Right” is an even or fair exchange so that both parties benefit. Moral reasoning guided by a sense of “fair play.” |

|

| II. | Conventional Level |

| Moral reasoning is guided by conformity to social roles, rules, and expectations that the person has learned and internalized. Stage 3: Interpersonal Expectations “Right” is being a “good” person by conforming to social expectations, such as showing concern for others and following rules set by others so as to win their approval. Stage 4: Law and Order “Right” is helping maintain social order by doing one’s duty, obeying laws simply because they are laws, and showing respect for authorities simply because they are authorities. |

|

| III. | Postconventional Level |

| Moral reasoning is guided by internalized legal and moral principles that protect the rights of all members of society. Stage 5: Legal Principles “Right” is helping protect the basic rights of all members of society by upholding legalistic principles that promote the values of fairness, justice, equality, and democracy. Stage 6: Universal Moral Principles “Right” is determined by self-chosen ethical principles that reflect the person’s respect for ideals such as nonviolence, equality, and human dignity. If these moral principles conflict with democratically determined laws, the person’s self-chosen moral principles take precedence. |

|

| Sources: Research from Kohlberg (1981) and Colby & others (1983). | |

Kohlberg (1984) found that the responses of children under the age of 10 reflected preconventional moral reasoning based on self-interest—avoiding punishment and maximizing personal gain. Beginning in late childhood and continuing through adolescence and adulthood, responses typically reflected conventional moral reasoning, which emphasizes social roles, rules, and obligations. Thus, the progression from preconventional to conventional moral reasoning is closely associated with age-related cognitive abilities (Eisenberg & others, 2005; Olthof & others, 2008).

Do people inevitably advance from conventional to postconventional moral reasoning, as Kohlberg once thought? In a 20-year longitudinal study, Kohlberg followed a group of boys from late childhood through early adulthood. Of the 58 participants in the study, only 8 occasionally displayed stage 5 reasoning, which emphasizes respect for legal principles that protect all members of society. None of the participants showed stage 6 reasoning, which reflects self-chosen ethical principles that are universally applied (Colby & others, 1983). Kohlberg and his colleagues eventually dropped stage 6 from the theory, partly because clear-cut expressions of “universal moral principles” were so rare (Gibbs, 2003; Rest, 1983).

The hallmark of morality resides less in the ability to resolve abstract moral dilemmas or even figure out how, ideally, others should behave; the hallmark resides more in people’s tendency to apply the same moral standards to themselves that they apply to others and to function in accordance with them.

—Dennis Krebs and Kathy Denton (2006)

Kohlberg’s original belief that the development of abstract thinking in adolescence naturally and invariably leads people to the formation of idealistic moral principles has not been supported. Only a few exceptional people display the philosophical ideals in Kohlberg’s highest level of moral reasoning. The normal course of changes in moral reasoning for most people seems to be captured by Kohlberg’s first four stages (Colby & Kohlberg, 1984). By adulthood, the predominant form of moral reasoning is conventional moral reasoning, reflecting the importance of social roles and rules.

Kohlberg’s theory has been criticized on several grounds (see Krebs & Denton, 2005, 2006). Probably the most important criticism of Kohlberg’s theory is that moral reasoning doesn’t always predict moral behavior. People don’t necessarily respond to real-life dilemmas as they do to the hypothetical dilemmas that are used to test moral reasoning. Further, people can, and do, respond at different levels to different kinds of moral decisions. As Dennis Krebs and Kathy Denton (2005) point out, people are flexible in their real-world moral behavior: The goals that people pursue affect the types of moral judgments they make.

Similarly, Kohlberg’s theory is a theory of cognitive development, focusing on the type of conscious reasoning that people use to make moral decisions. However, as Jonathan Haidt (2007, 2010) points out, moral decisions in the real world are often affected by nonrational processes, such as emotional responses, custom, or tradition. For example, if your beloved dog was killed by a car, would it be morally wrong to cook and eat it? Many people would instinctively say “yes,” but probably not because of a well-considered, reasoned argument (Haidt & others, 1993). Haidt (2010) argues that moral decisions are always embedded in particular social contexts and influenced, often without our awareness, by emotions and social and cultural beliefs.

GENDER, CULTURE, AND MORAL REASONING

Other challenges to Kohlberg’s theory questioned whether it was as universal as its proponents claimed. Psychologist Carol Gilligan (1982) pointed out that Kohlberg’s early research was conducted entirely with male subjects, yet it became the basis for a theory applied to both males and females. Gilligan also noted that in most of Kohlberg’s stories, the main actor who faces the moral dilemma to be resolved is a male. When females are present in the stories, they often play a subordinate role. Thus, Gilligan believes that Kohlberg’s model reflects a male perspective that may not accurately depict the development of moral reasoning in women.

To Gilligan, Kohlberg’s model is based on an ethic of individual rights and justice, which is a more common perspective for men. In contrast, Gilligan (1982) developed a model of women’s moral development that is based on an ethic of care and responsibility. In her studies of women’s moral reasoning, Gilligan found that women tend to stress the importance of maintaining interpersonal relationships and responding to the needs of others, rather than focusing primarily on individual rights (Gilligan & Attanucci, 1988).

But do women use different criteria in making moral judgments? In a meta-analysis of studies on gender differences in moral reasoning, Sara Jaffee and Janet Shibley Hyde (2000) found only slight differences between male and female responses. Instead, evidence suggested that both men and women used a mix of care and justice perspectives. Thus, while disputing Gilligan’s idea that men and women had entirely different approaches to moral reasoning, Jaffe and Hyde found empirical support for Gilligan’s larger message: that Kohlberg’s theory did not adequately reflect the way that humans actually experienced moral decision making.

Despite Kohlberg’s belief that the stages of moral development were universal, culture also affects moral reasoning (Graham & others, 2011; Haidt, 2007). Kohlberg’s moral decisions focus on issues of harm, fairness, and justice. In many cultures, however, other domains are equally deemed to be morally important. For example, religious or spiritual purity, loyalty to one’s family or social group, respect for those in authority, and respect for tradition may also be seen as issues of morality. From this perspective, Kohlberg’s theory is narrowly focused on just one area of morality—harm, fairness, and justice.

Some cross-cultural psychologists also argue that Kohlberg’s stories and scoring system reflect a Western emphasis on individual rights and justice that is not shared in many cultures (Shweder & others, 1997). For example, Kohlberg’s moral stages do not reflect the sense of interdependence and the concern for the overall welfare of the group that is more common in collectivistic cultures. Cultural psychologist Harry Triandis (1994) reports an example of a response that does not fit into Kohlberg’s moral scheme. In response to the scenario in which the husband steals the drug to save his wife’s life, a man in New Guinea said, “If nobody helped him, I would say that we had caused the crime.” Thus, there are aspects of moral reasoning in other cultures that do not seem to be reflected in Kohlberg’s theory (Haidt, 2007; Shweder & Haidt, 1993).

Test your understanding of Adolescence with

.

.