9.6 Adult Development

KEY THEME

Development throughout adulthood is marked by exploration, physical changes, and the adoption of new social roles.

KEY QUESTIONS

What is emerging adulthood?

What physical changes take place in adulthood?

What are some general patterns of adult social development?

You can think of the developmental changes you experienced during infancy, childhood, and adolescence as early chapters in your life story. Those early life chapters helped set the tone for the primary focus of your life story—adulthood. During the half-century or more that constitutes adulthood, self-definition evolves as people achieve independence and take on new roles and responsibilities.

In his theory of psychosocial development, Erik Erikson (1982) described the two fundamental themes that dominate adulthood: love and work. According to Erikson (1964b, 1968), the primary psychosocial task of early adulthood is to form a committed, mutually enhancing, intimate relationship with another person. During middle adulthood, the primary psychosocial task is generativity—to contribute to future generations through your children, your career, and other meaningful activities. In this section, we’ll consider both themes as we continue our journey through the lifespan.

Emerging Adulthood

At one time, adolescence marked the end of childhood and the beginning of adulthood. For example, Fern was barely 19 years old when she married Erv at the close of the second World War, and she had three children by the time she was 25. Even as recently as the mid-1970s, most young people moved into the adult roles of stable work, marriage, and parenthood shortly after high school (Arnett, 2000, 2004). In the United States and other industrialized countries today, however, most young adults do not fully transition to adult roles until their late 20s. One reason is the need for additional education or training before entering the adult workforce. According to developmental psychologist Jeffrey Jensen Arnett (2000, 2004, 2010), the period from the late teens until the mid- to late-20s is a distinct stage of the lifespan, called emerging adulthood.

emerging adulthood

In industrialized countries, the stage of lifespan from approximately the late teens to the mid- to late-20s, which is characterized by exploration, instability, and flexibility in social roles, vocational choices, and relationships.

According to Erikson’s (1964) theory, the identity conflict should be fully resolved by the end of adolescence. However, Arnett (2010) contends that in today’s industrialized cultures, identity is not fully resolved until the mid- or late-20s. Instead, he writes, “It is during emerging adulthood, not adolescence, that most young people explore the options available to them in love and work and move towards making enduring choices.”

Many emerging adults feel “in between”: they are no longer adolescents, but not quite adults. Although some find this instability unsettling and disorienting, several studies have found that well-being and self-esteem steadily rise over the course of emerging adulthood for most people (Galambos & others, 2006; Schulenberg & Zarrett, 2006).

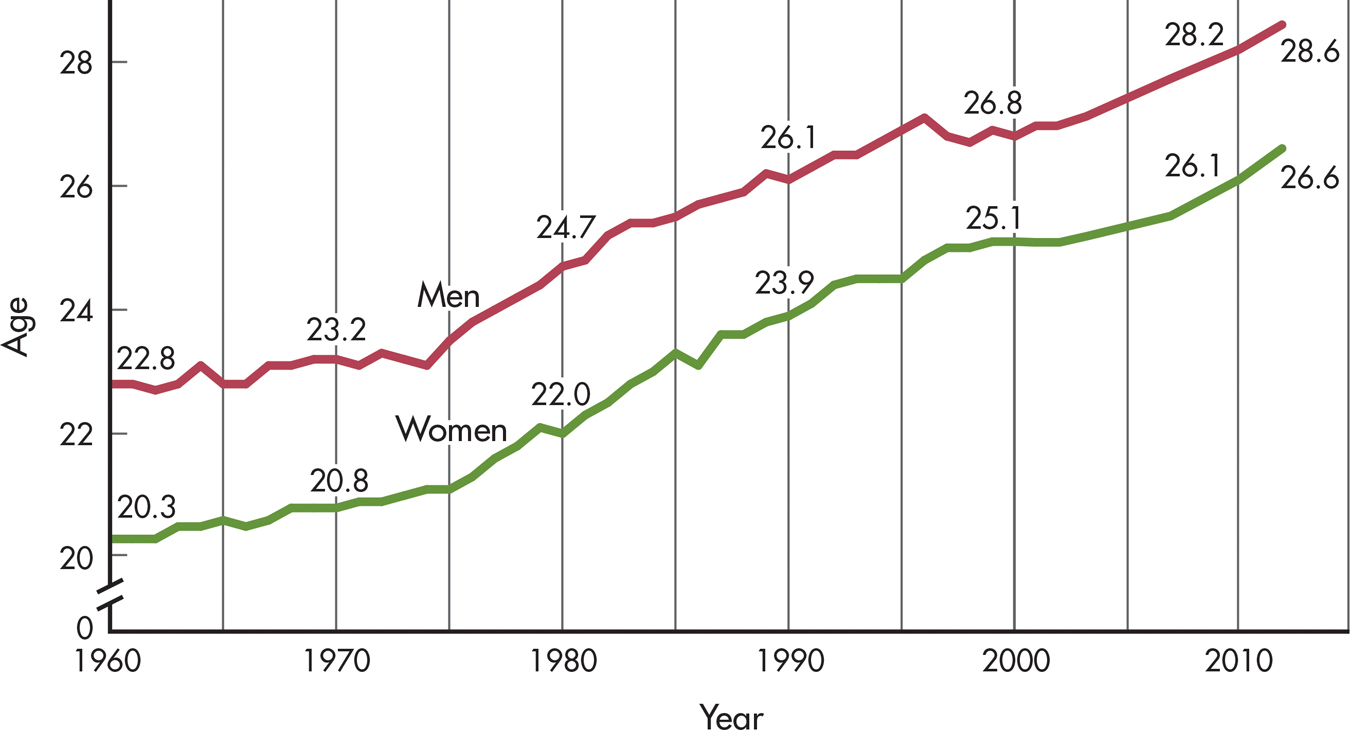

While some emerging adults establish long-term, stable relationships, in general relationships during emerging adulthood are characterized by exploration. “Hooking up” during the college and post-college years is common (see the In Focus box in Chapter 10). Compared to their parents and grandparents, today’s emerging adults are waiting much longer to get married. As FIGURE 9.5 shows, in 1970 the median age for a first marriage was 23 for men and 21 for women. By 2010 that figure had increased to 28 for men and 26 for women. Many emerging adults postpone marriage until their late 20s or early 30s so they can finish their education and become established in a career (Bernstein, 2010).

Emerging adulthood is a time of life when many different directions remain possible, when little about the future has been decided for certain, [and] when the scope of independent exploration of life’s possibilities is greater for most people than it will ever be at any other period of the life course.

—Jeffrey Jensen Arnett (2000)

Emerging adults also actively explore different career options (Hamilton & Hamilton, 2006). On average, emerging adults hold down an average of seven different jobs during their 20s (Arnett, 2004).

Is emerging adulthood a universal period of development? The answer appears to be no. According to Arnett (2011), emerging adulthood exists only in cultures in which adult responsibilities and roles are postponed until the 20s. This pattern occurs most typically in industrialized or post-industrialized countries. Even within industrialized countries, however, emerging adulthood may not characterize the developmental trajectory of all young adults. For example, members of minority groups, immigrants, and young adults who enter directly into the workforce rather than seeking college or university education are all less likely to experience emerging adulthood as a distinct period of exploration and change.

Physical Changes in Adulthood

Your unique genetic heritage greatly influences the unfolding of certain physical changes during adulthood, such as when your hair begins to thin and turn gray. Such genetically influenced changes can vary significantly from one person to another.

However, genetic heritage is not destiny. The lifestyle choices that people make in young and middle adulthood influence the aging process. Staying physically and mentally active, avoiding tobacco products and other harmful substances, and eating a healthy diet can both slow and minimize the physical declines that are typically associated with aging.

Another potent environmental force is simply the passage of time. Decades of use and environmental exposure take a toll on the body. Wrinkles begin to appear as we approach the age of 40, largely because of a loss of skin elasticity combined with years of making the same facial expressions. With each decade after age 20, the efficiency of various body organs declines. For example, lung capacity decreases, as does the amount of blood pumped by the heart, though these changes are usually not noticeable until late adulthood.

Physical strength typically peaks in early adulthood, the 20s and 30s. By middle adulthood, roughly from the 40s to the mid-60s, physical strength and endurance gradually decline. Physical and mental reaction times also begin to slow during middle adulthood. During late adulthood, from the mid-60s on, physical stamina and reaction time tend to decline further and faster.

Significant reproductive and hormonal changes also occur during adulthood. In women, menopause, the cessation of menstruation, signals the end of reproductive capacity and occurs anytime from the late 30s to the early 50s. For some women, menopause involves unpleasant symptoms, such as hot flashes, which are rapid and extreme increases in body temperature (Umland, 2008). Other symptoms may include night sweats and disturbances in sex drive, sleep, eating, weight, and motivation. Emotional symptoms may include depression, sadness, and emotional instability (E. Freeman, 2010).

menopause

The natural cessation of menstruation and the end of reproductive capacity in women.

Cultural stereotypes reinforce the notion that menopause is mostly a negative experience (APA, 2007). However, many women experience “postmenopausal zest.” Freed of menstruation, childbearing, and worries about becoming pregnant, many women feel a renewed sense of energy, freedom, and happiness. Postmenopausal women often develop a new sense of identity, become more assertive, and pursue new aspirations (Fahs, 2007). In many cultures, postmenopausal women are valued for their experience and wisdom (Robinson, 2002).

Middle-aged men do not experience an abrupt end to their reproductive capability. However, they do experience a gradual decline in testosterone levels, a condition sometimes called andropause (Hochreiter & others, 2005). Decreased levels of the hormone testosterone cause changes in physical and psychological health. These changes include loss of lean muscle, increased body fat, weakened bones, reduced sexual motivation and function, and cognitive declines (Harman, 2005). Emotional problems such as depression and irritability may also occur.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that many middle-aged people experience a “midlife crisis”?

Does the loss of reproductive capability trigger a “midlife crisis” in women, or especially, in men? No. Consistently, psychological research has shown that there is no such thing as a midlife crisis (see Clay, 2003; Sneed & others, 2012). Instead, most men and women who experienced a “crisis” of depression or despair during middle age also experienced depression, anxiety, and similar crises in young adulthood (Wethington, 2000).

Social Development in Adulthood

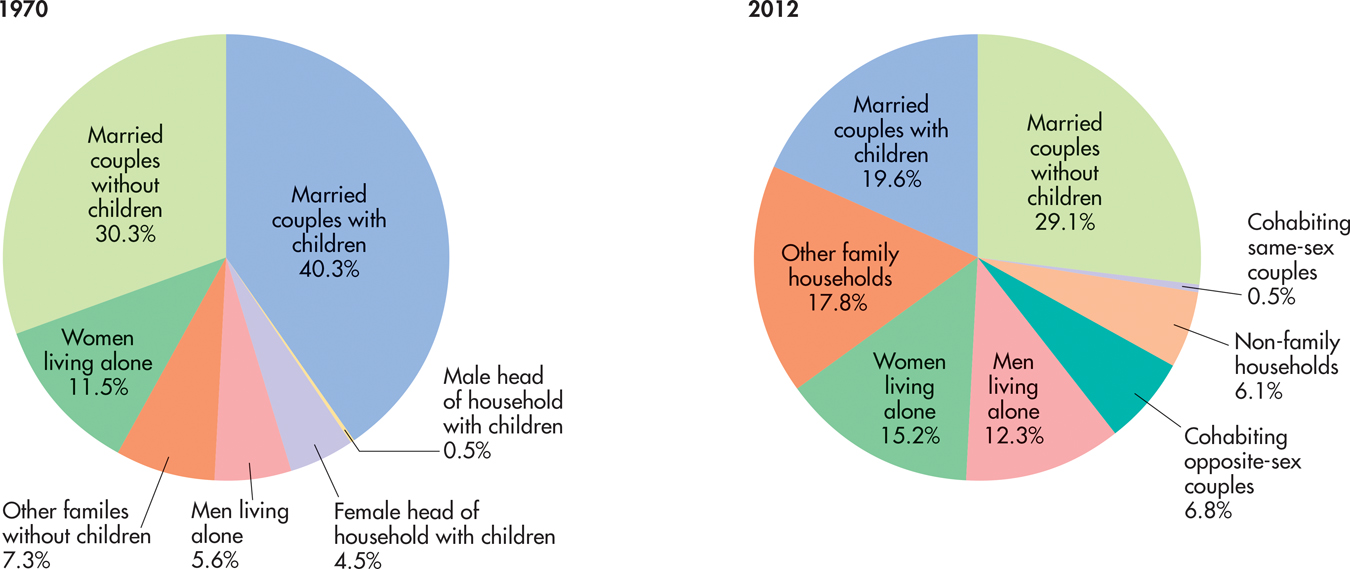

The “traditional” track of achieving intimacy in adulthood was once to find a mate, get married, and start and raise a family. Today, however, the structure of American families varies widely (see FIGURE 9.6). For example, the number of unmarried couples living together has increased dramatically—to well over 8 million couples in 2012 (Vespa & others, 2013). Currently, more than 30 percent of children are being raised by a single parent.

Given that more than half of all first marriages end in divorce, the phenomenon of remarrying and starting a second family later in life is not unusual. As divorce has become more common, the number of single parents and stepfamilies has also risen. And among married couples, some opt for a child-free life together. There are also gay and lesbian couples who, like many heterosexual couples, are committed to a long-term, monogamous relationship (Balsam & others, 2008; Goldberg, 2010; Rothblum & Hope, 2009).

Such diversity in adult relationships reflects the fact that adult social development does not always follow a predictable pattern. As you travel through adulthood, your life story may include many unanticipated twists in the plot and changes in the cast of characters. Just as the “traditional” family structure has its joys and heartaches, so do other configurations of intimate and family relationships. In the final analysis, any relationship that promotes the overall sense of happiness and well-being of the people involved is a successful one.

THE TRANSITION TO PARENTHOODKIDS ‘R’ US?

Although it is commonly believed that children strengthen the marital bond, marital satisfaction and time together tend to decline after the birth of the first child (Doss & others, 2009; Lawrence & others, 2010). For all the joy that can be derived from watching a child grow and experience the world, the first child’s arrival creates a whole new set of responsibilities, pushes, and pulls on the marital relationship.

Without question, parenthood fundamentally alters your identity as an adult. With the birth or adoption of your first child, you take on a commitment to nurture the physical, emotional, social, and intellectual well-being of the next generation. This change in your identity can be a struggle, especially if the transition to parenthood was more of a surprise than a planned event (Grussu & others, 2005).

Parenthood is further complicated by the fact that children are not born speaking fluently, so you can’t immediately enlighten them about the constraints of adult schedules, deadlines, finances, and physical energy. Instead, you must continually strive to adapt lovingly and patiently to your child’s needs while managing all the other priorities in your life.

Not all couples experience a decline in marital satisfaction after the birth of a child. The hassles and headaches of child rearing can be minimized if the marital relationship is warm and positive, and if both husband and wife share household and child-care responsibilities (Tsang & others, 2003). The transition to parenthood is also smoother if you’re blessed with a child who is born with a good disposition. Parents of babies with an “easy” temperament find it less difficult to adjust to their new role and maintain a healthy marital relationship (Mehall & others, 2009).

That many couples are marrying at a later age and waiting until their 30s to start a family also seems to be advantageous. Becoming a parent at an older age and waiting longer after marriage to start a family may ease the adjustment to parenthood. Why? Largely because the couple is more mature, the marital relationship is typically more stable, and finances are more secure (Hatton & others, 2010; Nelson & others, 2014).

In developed societies, dual-career families have become increasingly common. However, the career tracks of men and women often differ if they have children. Although today’s fathers are more actively involved in child rearing than were fathers in previous generations, women still tend to have primary responsibility for child care (Meier & others, 2006). Thus, married women with children are much more likely than are single women or childless women to interrupt their careers, leave their jobs, or switch to part-time work because of child-rearing responsibilities. As a consequence, women with children tend to earn less than childless women (Gangl & Ziefle, 2009).

Many working parents are concerned about the effects of nonparental care on their children. Earlier in the chapter, we discussed the importance of attachment relationships between young children and their primary caregivers. In the Critical Thinking box below, we take a close look at what psychologists have learned about the effects of day care on attachment and other aspects of development.

Do adults, particularly women, experience greater stress because of the conflicting demands of career, marriage, and family? Not necessarily. Generally, multiple roles seem to provide both men and women with a greater potential for increased feelings of self-esteem, happiness, and competence (Cinamon & others, 2007). The critical factor seems to be not the number of roles that people take on but the quality of their experiences on the job, in marriage, and as a parent (Lee & Phillips, 2006; Plaisier & others, 2008). When experiences in different roles are positive and satisfying, psychological well-being is enhanced. However, when work is dissatisfying, finding high-quality child care is difficult, and making ends meet is a never-ending struggle, stress can escalate and psychological well-being can plummet—for either sex (Bakker & others, 2008).

CRITICAL THINKING

The Effects of Child Care on Attachment and Development

The majority of children under the age of 5 in the United States—more than 11 million children—are in some type of child care (Phillips & Lowenstein, 2011). On average, the infants, toddlers, and preschoolers of working parents spend 36 hours a week in child care (NACCRRA, 2010). Does extensive day care during the first years of life create insecurely attached infants and toddlers? Does it produce negative effects in later childhood? Let’s look at the evidence.

Developmental psychologist Jay Belsky (1992, 2001, 2002) sparked considerable controversy when he first published studies showing that infants under a year old were more likely to demonstrate insecure attachment if they experienced over 30 hours of day care per week. Based on his research, Belsky contended that children who entered full-time day care before their first birthday were “at risk” to be insecurely attached to their parents. He also claimed that extensive experience with nonmaternal care was linked to aggressive behavior in preschool and kindergarten.

However, reviewing the data in Belsky’s and other early studies, psychologist Alison Clarke-Stewart (1989, 1992) pointed out that the actual difference in attachment was quite small when infants experiencing day care were compared with infants cared for by a parent. The proportion of insecurely attached infants in day care is only slightly higher than the proportion typically found in the general population (Lamb & others, 1992).

In other words, most of the children who had started day care in infancy were securely attached, just like most of the children who had not experienced extensive day care during infancy (Phillips & Lowenstein, 2011). Similarly, a large, long-term study of the effects of child care on attachment found that spending more hours per week in day care was associated with insecure attachment only in preschoolers who also experienced less sensitive and less responsive maternal care (NICHD, 2006). Preschoolers whose mothers were sensitive and responsive showed no greater likelihood of being insecurely attached, regardless of the number of hours spent in day care.

Researchers agree that the quality of child care is a key factor in facilitating secure attachment in early childhood and preventing problems in later childhood (NICHD, 2003a, 2003b; Vandell & others, 2010). Many studies have found that children who experience high-quality child care tend to be more sociable, better adjusted, and more academically competent than children who experience low-quality care, even well into their teens (Belsky & others, 2007; Vandell & others, 2010). They also have fewer behavior problems than children who experience lower-quality care (McCartney & others, 2010).

Child care is just one aspect of a child’s developmental environment. Sensitive parenting and the quality of caregiving in the child’s home have been found to have an even greater influence on social, emotional, and cognitive development than the quality of child care (Belsky & others, 2007).

Clearly, then, day care in and of itself does not necessarily lead to undesirable outcomes (Belsky, 2009). The critical factor is the quality of care (Phillips & Lowenstein, 2011). High-quality day care can benefit children, even when it begins in early infancy. In contrast, low-quality care can contribute to social and academic problems in later childhood (Muenchow & Marsland, 2007). Unfortunately, in many areas of the United States, high-quality day care is not readily available or is prohibitively expensive (Phillips & Lowenstein, 2011).

Characteristics of High-Quality Child Care

The setting meets state and local standards, and is accredited by a professional organization, such as the National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Warm, responsive caregivers encourage children’s play and learning.

Groups of children and adults are consistent over time, helping foster stable, positive relationships. Low staff turnover is essential.

Groups are small enough to provide the individual attention that very young children need.

A minimum of two adults care for no more than 8 infants, 12 toddlers, or 20 four- and five-year-olds.

Caregivers are trained in principles of child development and learning.

Developmentally appropriate learning materials and toys are available that offer interesting, safe, and achievable activities.

Sources: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, 2006; National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2009; National Association of Child Care Resource & Referral Agencies, 2008.

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

Why is it difficult to definitively measure the effects of day care on children?

Given the benefits of high-quality child care, should the availability of affordable, high-quality care be a national priority?

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true that marital happiness declines when children leave the home, something called the “empty nest syndrome”?

Although marital satisfaction declines when people first become parents, it rises again after children leave home (Gorchoff & others, 2008). Thus, most parents do not experience feelings of sadness, emptiness, and loss when their last child leaves home, often called the “empty nest syndrome” (Bouchard, 2014). Successfully launching your children into the adult world represents the attainment of the ultimate parental goal. There is also more time to spend in leisure activities with your spouse. Not surprisingly, then, marital satisfaction tends to increase steadily once children are out of the nest and flying on their own. Relatively recent is the new phenomenon of boomerang kids—adult children returning home after a brief period on their own because of economic pressures. Just as children’s departure positively affects marital satisfaction, the return of those same children can have a negative impact on the marital relationship (Bouchard, 2014; Umberson & others, 2005).