10.3 Gender-Role Development: BLUE BEARS AND PINK BUNNIES

KEY THEME

Gender roles are the behaviors, attitudes, and traits that a given culture associates with masculinity and femininity.

KEY QUESTIONS

What gender differences develop during childhood?

How do social learning theory and gender schema theory explain gender-role development?

Being male or female does make a vast difference in most societies. In the United States, newborn babies are often “color-coded” within moments of their birth. When Sandy and Don’s daughter was born, she was immediately wrapped in a pink blanket with bunnies, just like the other female infants in the nursery. The male infants were also color-coded by gender—they had blue blankets with little bears. That, of course, is just the beginning of life in a world strongly influenced by gender (see Denny & Pittman, 2007). Many parents may try to raise their children in a “gender-neutral” fashion. However, research shows that even 1-year-olds are already sensitive to subtle gender differences in behavior and mannerisms (Poulin-Dubois & Serbin, 2006).

Gender Differences in Childhood Behavior: SPIDER-MAN VERSUS BARBIE

Most toddlers begin using gender labels between the ages of 18 and 21 months. And, roughly between the ages of 2 and 3, children can identify themselves and other children as boys or girls, although the details are still a bit fuzzy to them (Zosuls & others, 2009). Preschoolers don’t yet understand that sex is determined by physical characteristics. This is not surprising, considering that the biologically defining sex characteristics—the genitals—are hidden from view most of the time. Instead, young children identify the sexes in terms of external attributes, such as hairstyle, clothing, and activities.

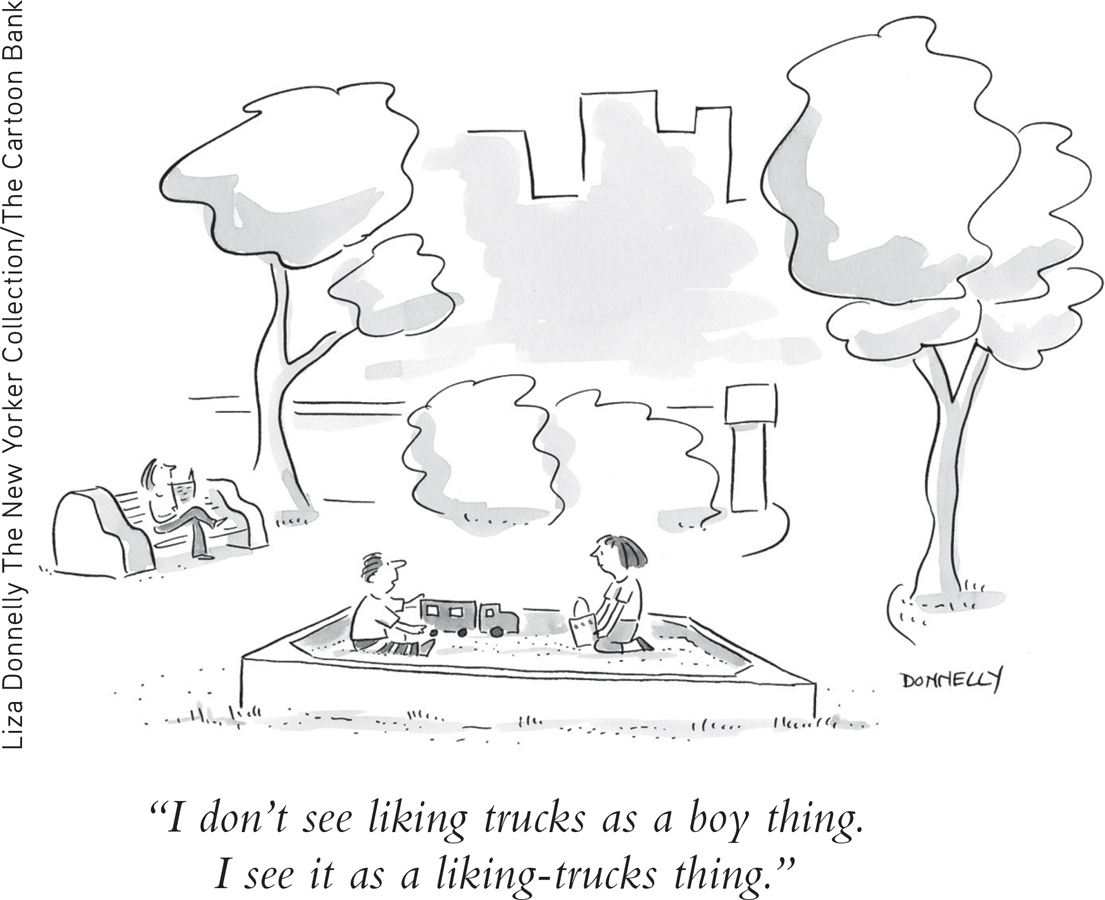

From about the age of 18 months to the age of 2 years, sex differences in behavior begin to emerge (Miller & others, 2006). These differences become more pronounced throughout early childhood. Toddler girls play more with soft toys and dolls, and ask for help from adults more than toddler boys do. Toddler boys play more with blocks and transportation toys, such as trucks and wagons. They also play more actively than do girls (see Ruble & others, 2006).

Roughly between the ages of 2 and 3, preschoolers start acquiring gender-role stereotypes for toys, clothing, household objects, games, and work. From the age of about 3 on, there are consistent gender differences in preferred toys and play activities. Boys play more with balls, blocks, and toy vehicles. Girls play more with dolls and domestic toys and engage in more dressing up and art activities. By the age of 3, children have developed a clear preference for toys that are associated with their own sex. This tendency continues throughout childhood (Berenbaum & others, 2008; Freeman, 2007).

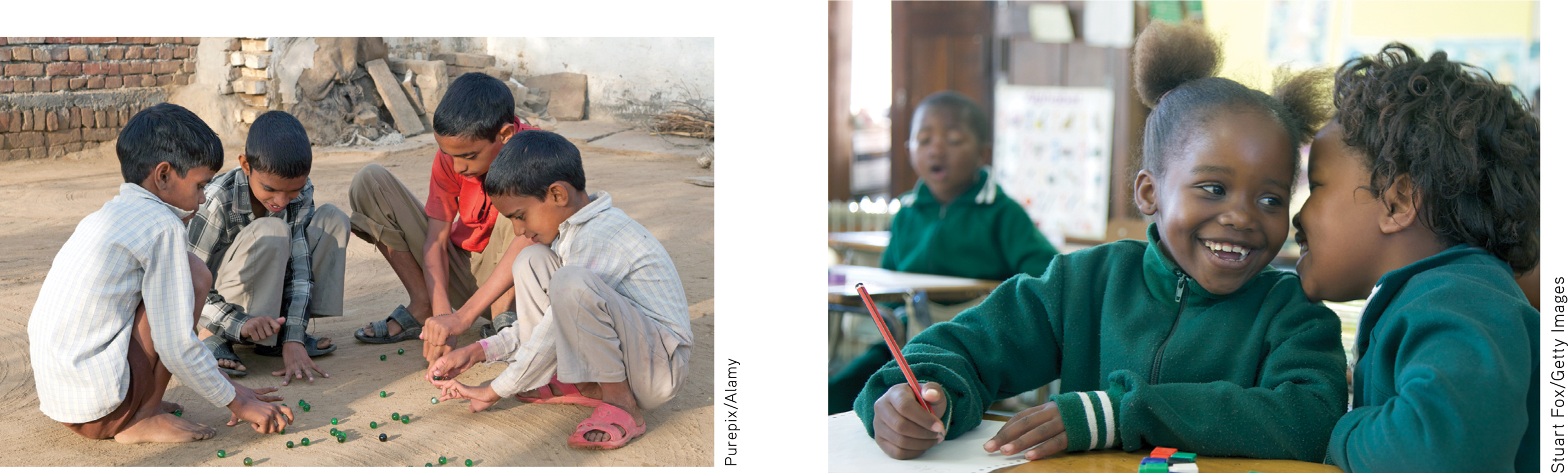

Children also develop a strong preference for playing with members of their own sex—girls with girls and boys with boys (Egan & Perry, 2001; Fridell & others, 2006). It’s not uncommon to hear boys refer to girls as “icky” and girls refer to boys as “mean” or “rough.” And, in fact, preschool boys do play more roughly than girls, cover more territory, and play in larger groups. Throughout the remainder of childhood, boys and girls play primarily with members of their own sex (Hoffmann & Powlishta, 2001; Martin & Ruble, 2010).

Stuart Fox/Getty Images

According to psychologist Carole Beal (1994), boys and girls seem to almost create separate “social worlds,” each with its own style of interaction. They also learn particular ways of interacting that work well with peers of the same sex. For example, boys learn to assert themselves within a group of male friends. Girls tend to establish very close bonds with one or two friends. Girls learn to maintain their close friendships through compromise, conciliation, and verbal conflict resolution.

Children are far more rigid than adults in their beliefs in gender-role stereotypes. Children’s strong adherence to gender stereotypes may be a necessary step in developing a gender identity (Halim & Ruble, 2009). Boys are far more rigid than girls in their preferences for toys associated with their own sex. Their attitudes about the sexes are also more rigid than are those held by girls. As girls grow older, they become even more flexible in their views of sex-appropriate activities and attributes, but boys become even less flexible (Schmalz & Kerstetter, 2006).

Girls’ more flexible attitude toward gender roles may reflect society’s greater tolerance of girls who cross gender lines in attire and behavior. A girl who plays with boys, or who plays with boys’ toys, may develop the grudging respect of both sexes. But a boy who plays with girls or with girls’ toys may be ostracized by both sexes. Girls are often proud to be labeled a “tomboy,” but for many boys, being called a “sissy” is still the ultimate insult (Thorne, 1993).

!launch!

James has observed others’ expectations from the vantage point of having lived as both female and male at different points in his life. In his turning point story in the Prologue, the boy in the community garden took James’s shovel so “she” wouldn’t get “her” hands dirty. As a man, James frequently fields questions about why he is not into stereotypically masculine activities, such as weight lifting. James explains that he hates stereotypes, noting “I’m not the geek/nerd stereotype. But, if you are going to stick me in a category, I’m that one. I’m not a jock.” And he hates expectations about how he should dress: “Like you are not allowed to wear bright colors anymore because you’re a man?”

As we’ve seen, contrary to many people’s perceptions, there are very few signifi-cant differences between the sexes in either personality traits or intellectual abilities. Yet in many ways, children’s behavior mirrors the gender-role stereotypes that are predominant in our culture.

Question 10.4

fyey4SYwBONj59v8LBXDRF5ozqR+EotfKBVpQi4oQSxxC5Dqzb5SodBT+TyuAP22HxAjO90sUXw0fBgwWaosrqmIkX24TH5dpvBVyrYQcaw0NccmAG9aPxpb28Smi13p1W8yPX3fCUVsDfXqYt+S6DUYdR/aRnIynEqj3YdMTk8bM/sWwWJSd11QyiOsbcYDZ+GuK15hkK9jRY6T/pGBIsQ/tHX4ZeOSv9AQKd7ByQJ2MPNBRnyTtO3GMu9wkpcPnboqqfFQugoZzRO5MpKhq2ABDMo=Explaining Gender Differences: CONTEMPORARY THEORIES

Many theories have been proposed to explain the differing patterns of male and female behavior in our culture and in other cultures (see Reid & others, 2008). Gender theories have included findings and opinions from anthropology, sociology, neuroscience, medicine, philosophy, political science, economics, and religion. (Let’s face it, you probably have a few opinions on the issue yourself.) We won’t even attempt to cover the full range of ideas. Instead, we’ll describe three categories of influential psychological theories.

Historically, Alice Eagly and Wendy Wood (2013) observed, most psychologists have explained gender differences with a focus mostly on sociocultural explanations or mostly on biological explanations. Eagly and Wood argue that both viewpoints are important. Based on Eagly and Wood’s premise, we will discuss some explanations based primarily on sociocultural factors including social learning theory and gender schema theory, some explanations based primarily on biological factors including evolutionary theory, and interactionist theories that combine both approaches. In Chapter 11, Personality, we will discuss Freud’s ideas on the development of gender roles.

SOCIAL LEARNING THEORY: LEARNING GENDER ROLES

Based on the principles of learning, the social learning theory of gender-role development (also called cognitive social learning theory) contends that gender roles are learned through reinforcement, punishment, and modeling (Bussey & Bandura, 2004; Hyde, 2014). According to this theory, from a very young age, children are reinforced or rewarded when they display gender-appropriate behavior and punished when they do not.

social learning theory of gender-role development

The theory that gender roles are acquired through the basic processes of learning, including reinforcement, punishment, and modeling.

How do children acquire their understanding of gender norms? Children are exposed to many sources of information about gender roles, including television, video games, books, films, and observation of same-sex adult role models. Children also learn gender differences through modeling: They observe and then imitate the sex-typed behavior of significant adults and older children (Bronstein, 2006; Leaper & Friedman, 2007). By observing and imitating such models—whether it’s Mom cooking, Dad fixing things around the house, or a male superhero rescuing a helpless female on television—children come to understand that certain activities and attributes are considered more appropriate for one sex than for the other (Martin & Ruble, 2010).

Children are gender detectives who search for cues about gender—who should or should not engage in a particular activity, who can play with whom, and why girls and boys are different. Cognitive perspectives on gender development assume that children are actively searching for ways to find meaning in and make sense of the social world that surrounds them, and they do so by using the gender cues provided by society to help them interpret what they see and hear.

—Carol Lynn Martin and Diane Ruble (2004)

GENDER SCHEMA THEORY: CONSTRUCTING GENDER CATEGORIES

Gender schema theory, developed by Sandra Bem, incorporates some aspects of social learning theory (Renk & others, 2006; Martin & others, 2004). However, Bem (1981) approached gender-role development from a more strongly cognitive perspective. In contrast to the relatively passive role played by children in social learning theory, gender schema theory contends that children actively develop mental categories (or schemas) for masculinity and femininity (Martin & Ruble, 2004). That is, children actively organize information about other people and appropriate behavior, activities, and attributes into gender categories. Saying that “trucks are for boys and dolls are for girls” is an example of a gender schema. According to gender schema theory, children, like many adults, look at the world through “gender lenses” (Bem, 1987). Gender schemas influence how people pay attention to, perceive, interpret, and remember gender-relevant behavior. Gender schemas also seem to lead children to perceive members of their own sex more favorably than members of the opposite sex (Martin & others, 2002, 2004).

gender schema theory

The theory that gender-role development is influenced by the formation of schemas, or mental representations, of masculinity and femininity.

Like schemas in general (see Chapter 6), children’s gender schemas do seem to influence what they notice and remember. For example, in a classic experiment, 5-year-olds were shown pictures of children engaged in activities that violated common gender stereotypes, such as girls playing with trucks and boys playing with dolls (Martin & Halverson, 1981, 1983). A few days later, the 5-year-olds “remembered” that the boys had been playing with the trucks and the girls with the dolls!

Sun xinming-Imaginechina/AP Images

Children also readily assimilate new information into their existing gender schemas (Miller & others, 2006). In another classic study, 4- to 9-year-olds were given boxes of gender-neutral gadgets, such as hole punches (Bradbard & others, 1986). But some gadgets were labeled as “girl toys” and some as “boy toys.” The boys played more with the “boy” gadgets, and the girls played more with the “girl” gadgets. A week later, the children easily remembered which gadgets went with each sex. They also remembered more information about the gadgets that were associated with their own sex. Simply labeling the objects as belonging to boys or to girls had powerful consequences for the children’s behavior and memory—evidence of the importance of gender schemas in learning and remembering new information.

Gender schemas can be subtle. For example, a carefully designed study of almost 60 different children’s coloring books found that gender stereotypes were widespread. Males were more likely to be depicted as animals, adults, and superheroes. Females, on the other hand, were more likely to be depicted as children and humans (Fitzpatrick & McPherson, 2010).

Given the gender-schematized world we grow up in, it’s not surprising that gender stereotypes remain so pervasive and influential.

Question 10.5

a2n4o2thjaajJQ1bmZMDwp621QhmPt1T/O6C8k/Xid00A4BQJ4dA7pKj+on4NoDnUF6OLtP6G3gm1TzI5MO8S+HFkH2SoG1apA0RJheFIsMzJan2KvFl3vvYxoP0OY8VWZoTMOVPNuVLKFMiRU+aKi6qeFfAMo68iVKfbIhufR1wPpurephT/XB+MMLaRFrMIhb/CvjU4Xx2ahLuRm2Rj3/zqzHLUHo9n2xwDguKX91mQtiDskOcEYo+LraU0w7mwnoG55w+IRdHeEsLzakY8hb67YOC2Q4XuECYjfFT9gwsOw4TISYtt2fr+ZJtQumGEVOLUTIONARY THEORIES

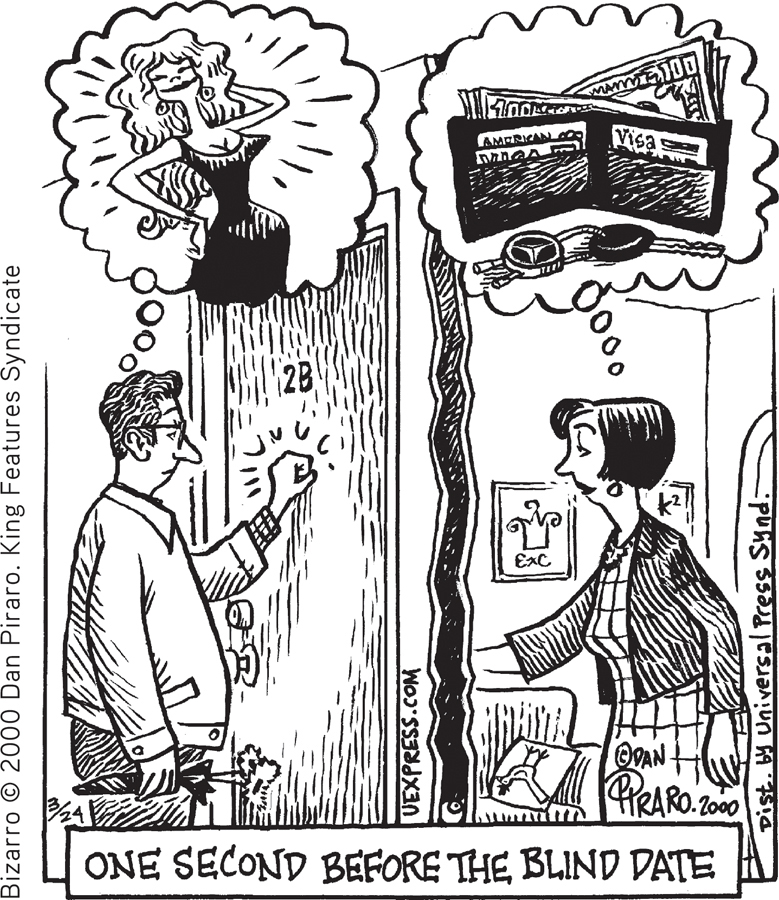

Some researchers use primarily biological explanations to explain gender differences in behavior and personality. Perhaps the most prominent of the biological explanations are those that cite evolution as the primary cause of many gender differences. According to the evolutionary approach, gender differences are the result of generations of the dual forces of sexual selection and parental investment (Hyde, 2014). Physical and psychological characteristics—related to either the choice of a mate or the investment in raising one’s children—that increased the likelihood of reproductive success tend to become more common. According to evolutionary psychology, behavior and traits are adaptive to the degree that they further the transmission of one’s genes to the next generation and beyond.

Evolutionary explanations have been explored for gender differences in a number of areas, including cognitive skills (see Cosmides & Tooby, 2013). For example, women seem to be better than men at spatial skills when the target is edible plants. Evolutionary researchers attribute this gender difference to a need for women to have foraging expertise in generations past (New & others, 2007).

However, the topic of mate preferences has received more research attention by evolutionary psychologists (Schmitt & others, 2012). To investigate mate preferences, psychologist David Buss (1994, 2009) coordinated a large-scale survey of more than 10,000 people in 37 different cultures. Across all cultures, Buss found, men were more likely than women to value youth and physical attractiveness in a potential mate. In contrast, women were more likely than men to value financial security, access to material resources, high status and education, and good financial prospects.

Buss, an evolutionary psychologist, interprets these gender differences as reflecting the different “mating strategies” of men and women (1995a, 2009, 2011). He contends that men and women face very different “adaptive problems” in selecting a mate. According to Buss (1995b, 1996), the adaptive problem for men is to identify and mate with women who are likely to be successful at bearing their children. Thus, men are more likely to place a high value on youth, because it is associated with fertility, and physical attractiveness, because it signals that the woman is probably physically healthy and has high-quality genes. Women also seek “good” genes, and thus they value men who are healthy and attractive. But women, on the other hand, have a more pressing need: making sure that the children they do bear survive to carry their genes into future generations (Buss, 2011). Thus, they seek men who possess the resources that the women and their offspring will need to survive.

The evolutionary explanation of sex differences, whether in mate preferences or other areas, is controversial (Confer & others, 2010). Some psychologists argue that it is overly deterministic and does not sufficiently acknowledge the role of culture, gender-role socialization, and other social factors (Eagly & Wood, 2011; Pedersen & others, 2010).

With respect to his research on mate preferences, Buss (2011) reported that his extensive survey also found that men and women in all 37 cultures agreed that the most important factor in choosing a mate was mutual attraction and love. And both sexes rated kindness, intelligence, emotional stability, health, and a pleasing personality as more important than a prospective mate’s financial resources or good looks.

Buss also flatly states that explaining some of the reasons that might underlie sexual inequality does not mean that sexual inequality is natural, correct, or justified. Rather, evolutionary psychologists believe that we must understand the conditions that foster sexual inequality in order to overcome or change those conditions (Buss & Schmitt, 2011).

INTERACTIONIST THEORIES

Eagly and Wood (2013) point out that there are many areas of agreement between those who favor sociocultural explanations and those who favor biological explanations. They encourage the development of interactionist theories that explain a given observation using a combination of explanations.

Let’s look at one example highlighted by Eagly and Wood (2013)—the division of labor along gender lines. Eagly and Wood observe that men tend to be physically larger and stronger than women and that women are biologically responsible for reproduction. These biological differences mean that it can be more efficient for men to be responsible for some activities—say, those that involve heavy lifting—and women to be responsible for others—say, those that involve nurturing an infant. Eagly and Wood also point out that there are social and psychological factors that create expectations in society that make the “division of labor seem natural and inevitable” (2013).

For example, since James began living as a man, several people have wondered why he does not engage in masculine athletic feats. “You should lift weights,” he’s been told as a man, but not as a woman. This suggestion draws on gender role beliefs about what women and men should do, rather than examining James’s biological abilities—or his preferences! Indeed, James’s biological abilities just before and after his transition to living as a man would have been the same. Conversely, your author Susan has seen women scoop crying babies from their husbands’ arms because the men were thought biologically incapable of soothing the baby.

Biology plays a role in what women and men do, but both women and men might be prevented from taking part in certain activities for reasons other than biological or physical limitations. Psychological and socially driven beliefs about talents and abilities can also limit opportunities and choices. From the interactionist perspective, it is the interplay of biological constraints and psychological and social constraints that drives the division of labor.

Eagly and Wood (2013) admit that it is challenging to incorporate the many biological and socicultural influences that might drive any given behavior. However, they see attempts at integrating explanations from the two categories as essential to gaining a fuller understanding of the psychology of sex and gender. For more on the role of culture in the expression of gender, see the Culture and Human Behavior box, “The Outward Display of Gender” on page 414.

Beyond Male and Female: VARIATIONS IN GENDER IDENTITY

In this section of the chapter, we explored gender differences and explanations of the development of gender roles. As we have seen, men and women are different, but they are not polar opposites. Instead, there is a great deal of overlap between them. Rather than being black and white, personality and biological differences more often reflect shades of gray. But whether those shades of gray tend to be light or dark, most people develop a clear sense of gender identity as either male or female. And, for most people, their sense of gender identity is consistent with their physical anatomy.

But for a significant minority of people, including James, gender identity and physical anatomy are not consistent. In some cases, biological factors blur the distinctions between male and female cells and body structures. During the course of prenatal development, chromosomal anomalies or atypical hormonal levels can affect the development of genitals or reproductive organs. The result is that there are other variations in gender identity beyond the typical categories of male or female.

INTERSEX INDIVIDUALS

An intersex individual, also referred to as a person with a disorder of sex development, is someone whose biological sex is ambiguous (American Psychological Association, 2006). In most cases, up until 6 or 7 weeks of gestation, the genital tissue is identical in male and female fetuses. Typically, after this point, the Y chromosome spurs the development of male genitalia. In the absence of the Y chromosome, female genitalia develop. But sometimes, this process is disrupted. With a disorder of sex development, reproductive structures may be partly male and partly female, tissues may be insensitive to the effects of hormones, or tissues may be exposed to hormone levels that are inconsistent with the person’s genetic sex (Pasterski, 2008).

intersex

Condition in which a person’s biological sex is ambiguous, often combining aspects of both male and female anatomy and/or physiology.

For example, girls with a syndrome called congenital adrenal hyperplasia are females who were exposed to abnormally high levels of testosterone during prenatal development, leading to genitals that may appear more masculine than feminine—having a larger clitoris that might resemble a penis, for example (Hines & others, 2004). Although these girls grow up to have a female gender identity, they often display masculine characteristics, such as facial hair.

Conversely, genetic males (XY) with a syndrome called androgen insensitivity syndrome produce normal levels of androgens, but their body tissues are insensitive to the hormones’ effects. These individuals have a small vagina, but no uterus, and undescended testes. Although they are genetic males, they are often labeled as girls because they don’t have a penis.

In past years, most infants who were born with ambiguous genitals were surgically “corrected” so as to have the appearance of one sex or the other. In some cases, the gender labels imposed at birth eventually conflicted with the adolescents’ developing gender identities.

Today, some intersex advocacy groups, such as the Intersex Society of North America (ISNA), oppose surgical and other interventions in infancy. The ISNA believes that the stigma associated with the condition is the biggest problem faced by intersex individuals (Chase, 2003, 2006). The ISNA recommends that parents and doctors should assign a gender to the newborn infant but should not perform irreversible surgery. Rather, surgery and hormone treatments, if needed, should be offered when the person is mature enough to provide informed consent—and after the intersex individual’s gender identity has been formed.

CULTURE AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

The Outward Display of Gender

We have outlined in this chapter the differences based on biological sex, as well as some based on gender. We have also emphasized the remarkable diversity among individual people of a given biological sex or gender identity. Is there also diversity in the expression of gender across cultures, and not just across individuals? In the United States, for example, there are fewer constraints on girls’ and women’s attire than there are on boys’ and men’s attire. Blue jeans on a girl are perfectly acceptable, but a skirt on a boy may raise a few eyebrows.

This gender-based rigidity for men may be, in part, culture-based. There are cultures that promote flexibility, at least in some circumstances. Some Zulu men and boys who live near Durban, South Africa and belong to a Baptist church participate in a ceremonial retreat twice a year (Yablonsky, 2013). During these month-long festivals, male church members wear “feminine” clothes, including skirts and headbands adorned with pompoms. South African artist Zwelethu Mthethwa, who has photographed this cultural practice, told a reporter, “Zulu culture is all about being macho, and I like the way they flip that.”

In other cultures, gender roles are rigidly defined, but it is sometimes acceptable for either a man or a woman to occupy the role of a man. In parts of the Balkans in southeastern Europe, including what are now Albania, Kosovo, and Montenegro, households were traditionally headed by men, and only men were allowed to own property; indeed, women were considered part of the property. When there was no male heir, a female heir often would be recruited to become a “sworn virgin” (or “kollovar”) and head the household (A. Young, 2000). In this role, she made decisions for her extended family on matters ranging from education to marriage. She also represented the family at village meetings.

Of course, for most women, the decision to become a sworn virgin was not based on gender identity, but rather on protection of the family’s assets. Nonetheless, in this very traditional society and era, sworn virgins lived as men, adopting the attire and hair-styles typical for men—sometimes even a traditionally male name. More importantly, they were accepted as men, routinely socializing and interacting with men on an equal basis. In exchange for the respect accorded a man, sworn virgins renounced any sexual or romantic relationships.

In other cultures, the range of acceptable gender roles is broadened for some people. In India, the hijra are considered a “third sex”—”neither man nor woman” (Nanda, 1999). The hijra include male-to-female transgender people, intersex people, and men who cross-dress without taking additional steps to become female (Hossain, 2012). Unlike many transgender people in other parts of the world, many hijra make no attempt to pass as female. Some even have beards (Nanda, 1999).

Beyond the identification as hijra by individual men, groups of hijra form a subculture within Indian society, often living as a community with a guru as leader (Kalra, 2012). Their practices draw from Muslim and Hindu traditions, and some hijra earn money by performing at ritual events such as births or marriages (Nanda, 1999). Hijra tend to be accepted, and even respected for their “otherworldliness,” to a much larger extent than transgender people who are not part of these communities or who live in other parts of the world. It is perhaps for this reason that the hijra community attracts a membership beyond transgender people (Nanda, 1999).

Although these examples are striking ones, they underline the role that culture plays for all of us in our gender expression—whether as a young girl who dresses as a tomboy in a western culture or as a man who wears a kilt and headband as part of a Baptist tradition in Zulu cultures. Cultural expectations can constrain or broaden our gender-related choices.

TRANSGENDER INDIVIDUALS

In contrast to intersex individuals, transgender individuals are anatomically “normal”—they are biologically male or female. However, their gender identity is in conflict with their biological sex (Sohn & Bosinski, 2007). A transgender man, such as James, is an anatomical female who identifies with or wishes to become male. A transgender woman is an anatomical male who identifies with or wishes to become female. And, a cisgender man or woman refers to people whose anatomy matches their gender identity, such as a biological woman who identifies as a woman. Because this situation is viewed as the norm, the term is infrequently used.

transgender

Condition in which a person’s psychological gender identity conflicts with his or her biological sex.

Like James, the typical transgender person has the strong feeling, often present since childhood, of having been born in the body of the wrong sex (Cohen-Kettenis & Pfaff lin, 2010; Zucker & Cohen-Kettenis, 2008). Gender identity is distinct from sexual orientation. A transgender person may be homosexual, heterosexual, or bisexual. James, for example, identifies as a straight man, and is romantically interested in women. Some transgender individuals, who are often called transsexuals, choose to undergo sex reassignment, which involves hormone treatments and surgery to transform their physical body into the other sex.

transsexual

A transgendered person who undergoes surgery and hormone treatments to physically transform his or her body into the opposite sex.

Is transsexualism a psychological disorder? When extreme discomfort with one’s assigned gender causes significant psychological dysfunction, the diagnosis of gender dysphoria may be made (DSM-5, 2013). Previously called gender identity disorder, the language was recently changed to emphasize that it is the discomfort, and not the discrepancy, that is considered to be a psychological disorder. Most professionals today disagree with classifying gender-variant behaviors, attitudes, and feelings as a mental illness (Hill & others, 2007; Isay, 2004; Cohen-Kettenis & Pfafflin, 2010).

MYTH !lhtriangle! SCIENCE

Is it true that transgender people are homosexual?

Intersex and transgender individuals, including James, continue to face discrimination and prejudice in many aspects of their lives. Many intersex individuals have the additional challenge of growing up in ignorance of their medical background. But some would argue that their lives are not all that different from those of people with a more conventional gender identity. In line with that thought, we’d like you to consider the words of Jim Costich (2003)—writer, activist, father, and self-identified gay intersex man.

We have achieved nothing if we are not free and supported by our own community to be exactly who we are, just as we are, without being expected to refashion our personalities, psyches, bodies and spirits into something others find more acceptable. Ultimately every single person is confined, conflicted, marginalized, and minimalized in some way by the arbitrary, unreasonable, and impossible artificial gender expectations of our society. This is no less true for heterosexuals than for [intersex individuals]. Whenever we show them how parts of their story are like parts of our story, and vice versa, we knock another brick out of the gender wall.

Question 10.6

vVNqrdU/c7aMOr+lejWxD/tOY44SPc0EQGN51tQrkIemQlpFe8OW2P5/iQaxGgUQ5Sqcv0X/n+i8USoS9yMtvPyYw2sK3GD0AzFg3Lg+Icd9pgSEvdkuQuUkRL6ZrKU9rsBOL3rJ84ne01JNAb+Tc3pw90IhvuhYhrzHHRzkoz0en94gN91zEOi2mMMsAOftdhswd0Jef1lm+prrdAV3UbzP4MDG7cpi2zml8m5a8UavQ0sK2mPnLvyEvSNTWJsMInoZT4TmzdOZDIDEQTd4Mvq8Swp/SQCCrncCfHrJEzycCKn+o5njLgBN8kwT+fNX3tI3ArCdRllVJ2R6ONBOvd/oGznIaykUb2TcD91l75Yscepz5Z1tow==CONCEPT REVIEW 10.1

Aspects of Gender and Sexuality

Decide which term applies to each of the following examples. Choose from: gender schema theory, sex, gender-role stereotypes, social learning theory.

Question 10.7

| 1. | When Sebastian was born, the doctor saw his penis and said, “Mrs. Singh, it’s a boy!” ____________ |

Question 10.8

| 2. | Michael thinks that women are more patient and emotional than men and that men are more aggressive, logical, and rational than women. What do Michael’s expectations reflect? ____________ |

Question 10.9

| 3. | As a little boy, Kofi was scolded whenever he picked up a doll. But whenever he tried to throw a football to his father, his father beamed and praised him. As Kofi grew up, he ignored dolls and took every opportunity to get involved in sports. ____________ |

Question 10.10

| 4. | When 4-year-old Ines first met the 3-year-old twins, Jason and Kimberly, Jason was carrying a doll and Kimberly was wearing a toy tool belt. The next time Ines saw Jason, she asked, “Where’s your tool belt?” ____________ |

Test your understanding of Gender Stereotypes and Roles with

.

.