10.4 Human Sexuality

KEY THEME

Multiple factors are involved in understanding human sexuality.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the four stages of human sexual response?

How does sexual motivation differ among animal species?

What biological factors are involved in sexual motivation?

Psychologists consider the drive to have sex a basic human motive. But what exactly motivates that drive? Obviously, there are differences between sex and other basic motives, such as hunger. Engaging in sexual intercourse is essential to the survival of the human species, but it is not essential to the survival of any specific person. In other words, you’ll die if you don’t eat, but you won’t die if you don’t have sex.

First Things First: THE STAGES OF HUMAN SEXUAL RESPONSE

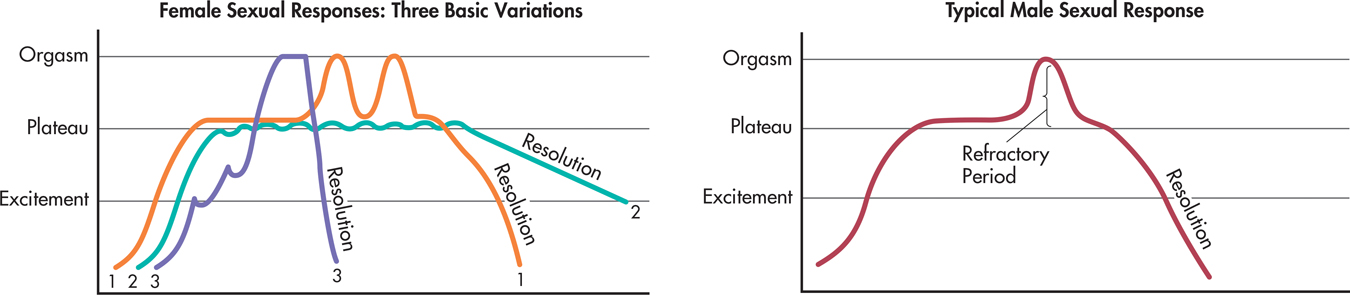

The human sexual response cycle was first mapped by sex research pioneers William Masters and Virginia Johnson during the 1950s and 1960s. In the name of science, Masters and Johnson observed hundreds of people engage in more than 10,000 episodes of sexual activity in their laboratory. Their findings, published in 1966, indicated that the human sexual response could be described as a cycle with four stages. Although it is simplified somewhat, FIGURE 10.3 depicts the basic patterns of sexual response for men and women.

STAGE 1: EXCITEMENT

The excitement phase marks the beginning of sexual arousal. Sexual arousal can occur in response to sexual fantasies or other sexually arousing stimuli, physical contact with another person, or masturbation. In both sexes, the excitement stage is accompanied by a variety of bodily changes in anticipation of sexual interaction.

STAGE 2: PLATEAU

In the second phase, the plateau phase, physical arousal builds. The penis becomes fully erect and sometimes secretes a few drops of fluid, which may contain active sperm. The testes increase in size. The clitoris withdraws under the clitoral hood but remains very sensitive to stimulation. The vaginal entrance tightens, putting pressure on the penis during intercourse. During the excitement and plateau stages, the degree of arousal may fluctuate up and down (Masters & others, 1995).

STAGE 3: ORGASM

Orgasm is the third and shortest phase of the sexual response cycle. The muscles in the vaginal walls and the uterus contract rhythmically, as do the muscles in and around the penis as the male ejaculates. Both men and women describe the subjective experience of orgasm in similar—and very positive—terms.

The vast majority of men experience one intense orgasm. But many women are capable of experiencing multiple orgasms. If sexual stimulation continues following orgasm, women may experience additional orgasms within a short period of time (King & others, 2010).

STAGE 4: RESOLUTION

Following orgasm, both sexes tend to experience a warm physical “glow” and a sense of well-being. Arousal slowly subsides and returns to normal levels in the resolution phase. The male experiences a refractory period, during which he is incapable of having another erection or orgasm.

Question 10.11

e7A93HkXnJNTCBJAPsOwc2injRMM0PgrC3dec7R1HWKoI5HX/IlXj9nYQAexx+9+u++jzr00XJnPGQlN7eA3jUvbnmq7+Ixy26rtNsLXE44WjknITyHCJzrL8hdv0N2eIVdXP3QvSr091JJc1SMvLq697WlBZTU/Klyq7mIfoG90G1N4vugqPNlZy3GpqeP4v3DzZeIM5Z5jQKQJ/VbZi38ZUlUpykU2GvNGcHIail3z8u0dYbvWHrtkKYtkdni4JzGKrjJeBehfL2yVB28Fg7XUf2LRvcZPO1GdCg==What Motivates Sexual Behavior?

In most animals, sexual behavior is biologically determined and triggered by hormonal changes in the female. During the cyclical period known as estrus, a female animal is fertile and receptive to male sexual advances. Roughly translated, the Greek word estrus means “frantic desire.” Indeed, the female animal will often actively signal her willingness to engage in sexual activity—as any owner of an unneutered female cat or dog that’s “in heat” can testify. In many, but not all, species, sexual activity takes place only when the female is in estrus.

As you go up the evolutionary scale, moving from relatively simple to more sophisticated animals, sexual behavior becomes less biologically determined and more subject to learning and environmental influences. Sexual behavior also becomes less limited to the goal of reproduction (Buss, 2007a, 2007b). For example, in some primate species, such as monkeys and apes, sexual activity can occur at any time, not just when the female is fertile. In these species, sexual interaction serves important social functions, defining and cementing relationships among the members of the primate group.

One rare species of chimplike apes, the bonobos of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, exhibits a surprising variety of sexual behaviors (de Waal, 2007; Parish & de Waal, 2000). Although most animals copulate, or have sex, with the male mounting the female from behind, bonobos often copulate face to face. Bonobos also engage in oral sex and intense tongue kissing. And bonobos seem to like variety. Along with having frequent heterosexual activity, whether the female is fertile or not, bonobos also engage in homosexual and group sex.

Emory University psychology professor Frans de Waal (1995, 2007), who has extensively studied bonobos, observes that their frequent and varied sexual behavior seems to serve important social functions. Sexual behavior is not limited to fulfilling the purpose of reproduction. Among the bonobos, sexual interaction is used to increase group cohesion, avoid conflict, and decrease tension that might be caused by competition for food. According to de Waal (1995), the bonobos’ motto seems to be “Make love, not war.”

In humans, of course, sexual behavior is not limited to a female’s fertile period (Buss, 2007a, b). And, motives for sexual behavior are not limited to reproduction (Meston & Buss, 2007, 2009). Some women experience monthly fluctuations in sexual interest and motivation that are related to the hormonal cycles that also regulate fertility. However, these changes are highly influenced by social and psychological factors, such as relationship quality (Gangestad & others, 2007; Thornhill, 2007). Even when a woman’s ovaries, which produce the female sex hormone estrogen, are surgically removed or stop functioning during menopause, there is little or no drop in sexual interest. In many nonhuman female mammals, however, removal of the ovaries results in a complete loss of interest in sexual activity. If injections of estrogen and other female sex hormones are given, the female animals’ sexual interest returns.

In male animals, removal of the testes (castration) typically causes a steep drop in sexual activity and interest, although the decline is more gradual in sexually experienced animals. Castration causes a significant decrease in levels of testosterone, the hormone responsible for male sexual development. When human males experience lowered levels of testosterone because of illness or castration, a similar drop in sexual interest tends to occur, although the effects vary among individuals (Wrobel & Karasek, 2008). Some men continue to lead a normal sex life for years, but others quickly lose all interest in sexual activity. In castrated men who experience a loss of sexual interest, injections of testosterone restore the sexual drive.

Testosterone is also involved in female sexual motivation (Davis & others, 2008). Most of the testosterone in a woman’s body is produced by her adrenal glands. If these glands are removed or malfunction, causing testosterone levels to become abnormally low, sexual interest often wanes. When supplemental testosterone is administered, the woman’s sex drive returns. Thus, in both men and women, sexual motivation is biologically influenced by the levels of the hormone testosterone in the body.

Of course, sexual behavior is greatly influenced by many different factors—social, cultural, and more. Could evolution have played a role?

Sexual Orientation: THE ELUSIVE SEARCH FOR AN EXPLANATION

KEY THEME

Sexual orientation refers to whether a person is attracted to members of the opposite sex, the same sex, or both sexes.

KEY QUESTIONS

Why is sexual orientation sometimes difficult to identify?

What factors have been associated with sexual orientation?

Given that biological factors seem to play an important role in motivating sexual desire, it seems only reasonable to ask whether biological factors also play a role in sexual orientation. Sexual orientation refers to whether a person is sexually aroused by members of the same sex, the opposite sex, or both sexes. A heterosexual person is sexually attracted to individuals of the other sex, a homosexual person to individuals of the same sex, and a bisexual person to individuals of both sexes. Technically, the term homosexual can be applied to either males or females. However, female homosexuals are usually called lesbians. Male homosexuals typically use the term gay to describe their sexual orientation. Some researchers have posited an additional orientation— asexual. Asexuality refers to people who are not sexually attracted to people of either sex, regardless of their actual sexual behavior (Bogaert, 2006b).

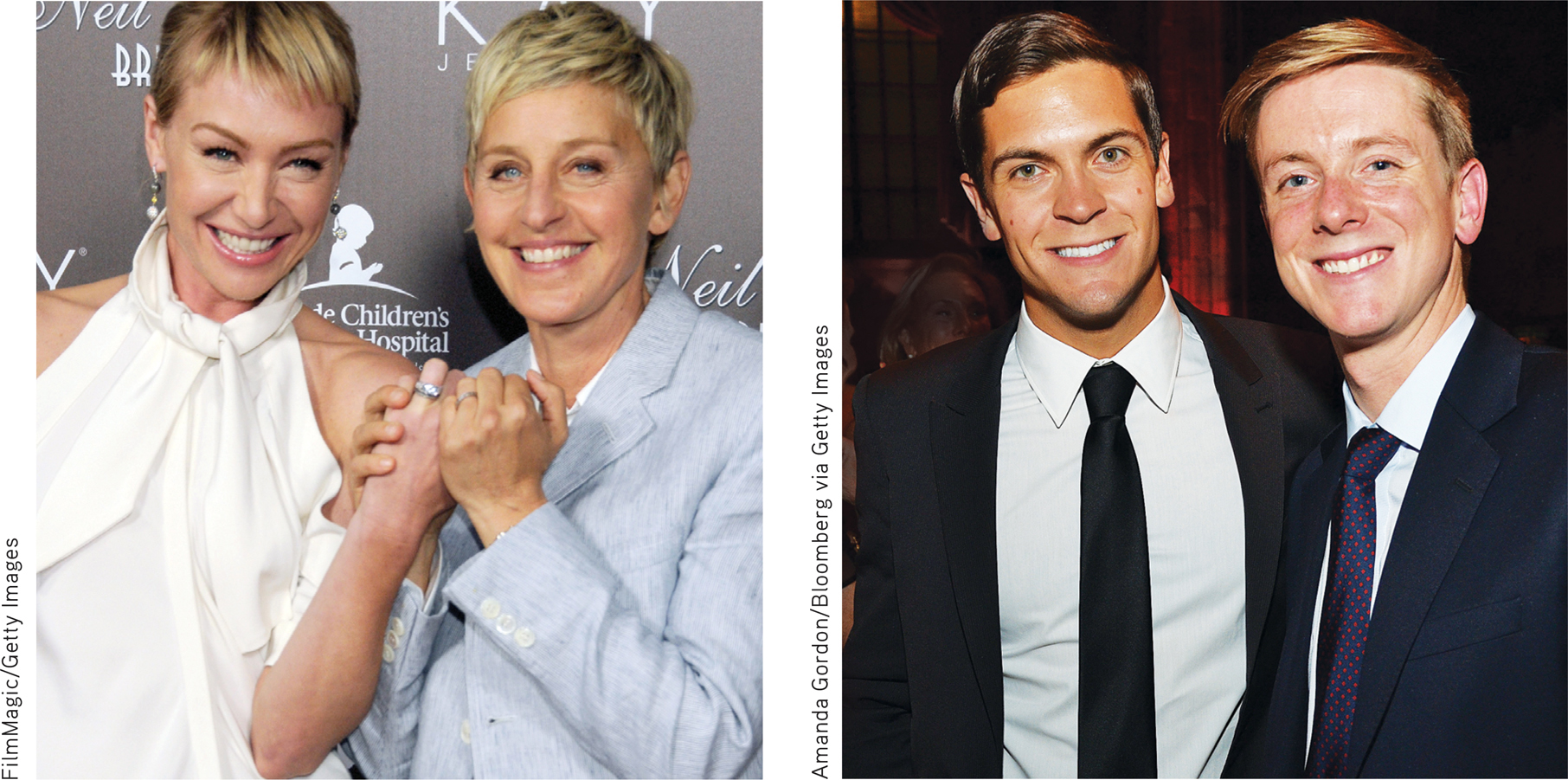

Also recently married are “power couple” Chris Hughes and Sean Eldridge. Here, Hughes, one of Facebook’s founders and editor-in-chief of The New Republic, attends a fundraiser with his spouse Eldridge, an investor and political activist. Hughes (2011) doesn’t like the term “power couple,” but says, “I don’t think we’ve ever used that term for ourselves, but I must say having a partner who has similar intensity in his days, a passion for work in the same way, it makes a difference to come home at night and have an intellectual partner. If that’s what a ‘power couple’ is, then great.”

Amanda Gordon/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Sexual orientation is not nearly as cut and dried as many people believe. Some people are exclusively heterosexual or homosexual, but others are less easy to categorize. Some people explicitly identify as “mostly,” but not exclusively, heterosexual or homosexual (Vrangalova & Savin-Williams, 2012). Some people who consider themselves heterosexual have had a homosexual experience at some point in their lives. In the same vein, many people who identify as homosexuals have had heterosexual experiences (Malcolm, 2008; Rieger & others, 2005). Other people consider themselves to be homosexual but have been involved in long-term, committed heterosexual relationships. Still others are asexual but engage in romantic or sexual relationships. The key points are that there is a range of sexual identity and there is not always a perfect correspondence between a particular person’s sexual identity, sexual desires, and sexual behaviors.

Determining the number of people who are homosexual, heterosexual, bisexual, or asexual is challenging. First, survey results vary depending on how the researchers define the terms homosexual, heterosexual, bisexual, and asexual (Bogaert, 2006b; Savin-Williams & Hope, 2009). Where the survey is conducted, how survey participants are selected, and how the survey questions are worded also affect the results.

Depending upon how sexual orientation is defined, estimates of the prevalence rate of homosexuality in the general population range from 1 percent to 21 percent (Savin-Williams, 2006). More important than the exact number of gays and lesbians is the recognition that gays and lesbians constitute a significant segment of the adult population. According to the most recent estimates, about 7% of women and 5% of men in the United States report having ever engaged in homosexual behavior (F. Xu & others, 2010a, 2010b). Asexuality has been studied much less than homosexuality. However, one study of over 18,000 people living in the United Kingdom found that about 1% of people reported no sexual attraction to either men or women (Bogaert, 2004).

WHAT DETERMINES SEXUAL ORIENTATION?

Despite considerable research on this question, psychologists and other researchers cannot say with certainty why people become homosexual or bisexual. For that matter, psychologists don’t know exactly why people become heterosexual either. Still, research on sexual orientation has pointed toward several general conclusions, especially with regard to homosexuality.

Evidence from multiple studies shows that genetics plays a role in determining sexual orientation (Rodriguez-Larralde & Paradisi, 2009). Most studies compare the incidence of homosexuality among pairs of identical twins (who have identical genes), fraternal twins (who are genetically as similar as any two nontwin siblings), and non-twin siblings. In both males and females, research has shown that the closer the degree of genetic relationship, the more likely it is that when one sibling is homosexual, the other would also be homosexual. Such studies have shown that genetics contributes to homosexual orientation in both men and women, although to a much lesser degree in women than men (Alanko & others, 2010; Långström & others, 2010).

However, genetics is only a partial explanation. In the largest twin studies to date, Swedish researchers showed that both genetic and nonshared environmental factors were involved in sexual orientation (Långström & others, 2008, 2010). What are “nonshared” environmental factors? Influences that are experienced by one, but not both, twins. More specifically, these are social and biological factors, rather than upbringing or family environment.

Sexual orientation does seem to be at least partly influenced by genetics (Hyde, 2005). However, that genetic influence is likely to be complex, involving the interaction of multiple genes, not a single “gay gene” (see Vilain, 2008). Beyond heredity, there is also evidence that sexual orientation may be influenced by other biological factors, such as prenatal exposure to sex hormones or other aspects of the prenatal environment (Hines, 2010).

For example, one intriguing finding is that the more older brothers a man has, the more likely he is to be homosexual (Blanchard, 2008; Blanchard & Lippa, 2008). Could a homosexual orientation be due to psychological factors, such as younger brothers being bullied or indulged by older male siblings? Or being treated differently by their parents, or some other family dynamic?

No. Collecting data on men who grew up in adoptive or blended families, Anthony Bogaert (2006a) found that only the number of biologically related older brothers predicted homosexual orientation. Living with older brothers who were not biologically related had no effect at all. As Anthony Bogaert (2007b) explains, “It’s not the brothers you lived with; it’s the environment within the same womb—sharing the same mom.” Researchers don’t have an explanation for the effect, which has been replicated in multiple studies (see Bogaert, 2007a). One suggestion is that carrying successive male children might trigger some sort of immune response in the mother that, in turn, influences brain development in the male fetus (James, 2006).

Finally, a number of researchers have discovered differences in brain function or structure among gay, lesbian, and heterosexual men and women (see LeVay, 2007; Savic & Lindström, 2008). However, most of these studies have proved small or inconclusive. It’s also important to note that there is no way of knowing whether brain differences are the cause or the effect of different patterns of sexual behavior.

I heard this on the news: “For every older brother a man has, the chances of him being gay increase by one-third.” I got a few problems with this theory. Specifically, Jimmy, Eddie, Billy, Tommy, Jay, Paul, and Peter. Those are my older brothers—seven brothers. By their math, I should be 233 percent gay. That’s getting up there.

—Stephen Colbert— The Colbert Report

In general, the only conclusion we can draw from these studies is that some biological factors are correlated with a homosexual orientation (Mustanski & others, 2002). As we’ve stressed, correlation does not necessarily indicate causality, only that two factors seem to occur together. So stronger conclusions about the role of genetic and biological factors in determining sexual orientation await more definitive research findings.

In an early study involving in-depth interviews with over 1,000 gay men and lesbian women, Alan Bell and his colleagues (1981) found that homosexuality was not the result of disturbed or abnormal family relationships. They also found that sexual orientation was determined before adolescence and long before the beginning of sexual activity. Gay men and lesbian women typically became aware of homosexual feelings about three years before they engaged in any such sexual activity. In this regard, the pattern was very similar to that of heterosexual children, in whom heterosexual feelings are aroused long before the child expresses them in some form of sexual behavior.

!launch!

Several researchers now believe that sexual orientation is established as early as age 6 (Strickland, 1995). Do children who later grow up to be homosexual differ from children who later grow up to be heterosexual? In at least one respect, there seems to be a difference.

Typically, boys and girls differ in their choice of toys, playmates, and activities from early childhood. However, evidence suggests that homosexual males and homosexual females are less likely to have followed the typical pattern of gender-specific behaviors in childhood (Bailey & others, 2000; Lippa, 2008; Rieger & others, 2008). Compared to heterosexual men, gay men recall engaging in more cross-sex-typed behavior during childhood. For example, they remembered playing more with girls than with other boys, preferring girls’ toys over boys’ toys, and disliking rough-and-tumble play. Lesbians are also more likely to recall cross-gender behavior in childhood. One study suggests that lesbians show an even greater degree of gender nonconformity than gays (Lippa, 2008).

A potential problem with such retrospective studies is that the participants may be biased in their recall of childhood events. One way to avoid that problem is by conducting a prospective study. A prospective study involves systematically observing a group of people over time to discover what factors are associated with the development of a particular trait, characteristic, or behavior.

One influential prospective study was conducted by Richard Green (1985, 1987). Green followed the development of sexual orientation in two groups of boys. The first group of boys had been referred to a mental health clinic because of their “feminine” behavior. He compared the development of these boys to a matched control group of boys who displayed typically “masculine” behavior in childhood. When all the boys were in their late teens, Green compared the two groups. He found that approximately 75 percent of the previously feminine boys were either bisexual or homosexual, as compared to only 4 percent of the control group.

Less is known about girls who are referred to clinics because of cross-gender behavior, partly because girls are less likely to be referred to clinics for “tomboy” behavior (Zucker & Cohen-Kettenis, 2008). However, Kelley Drummond and her colleagues (2008) found that cross-gender behavior in girls was also associated with the later development of bisexual or homosexual orientation, although at a lower rate than was true for boys.

Once sexual orientation is established, whether heterosexual or homosexual, it is highly resistant to change (Drescher & Zucker, 2006). The vast majority of homosexuals would be unable to change their orientation even if they wished to, just as the majority of heterosexuals would be unable to change their orientation if they wished to. Thus, it’s a mistake to assume that homosexuals have deliberately chosen their sexual orientation any more than heterosexuals have.

It seems clear that no single factor determines whether people identify themselves as homosexual, heterosexual, or bisexual (Patterson, 2008). Psychological, biological, social, and cultural factors are undoubtedly involved in determining sexual orientation. However, researchers are still unable to pinpoint exactly what those factors are and how they interact. As psychologist Bonnie Strickland (1995) has pointed out, “Sexual identity and orientation appear to be shaped by a complexity of biological, psychological, and social events. Gender identity and sexual orientation, at least for most people, especially gay men, occur early, are relatively fixed, and are difficult to change.” Whether we are homosexual, bisexual, or heterosexual, changing our sexual orientation is simply not possible.

Homosexuality has not been considered a sexual disorder by clinical psychologists or psychiatrists since 1973 (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Silverstein, 2009). Many research studies have also found that homosexuals who are comfortable with their sexual orientation are just as well adjusted as are heterosexuals (see Strickland, 1995). Indeed, in 2009 the American Psychological Association issued a resolution stating that there is no evidence to support therapies that aim to change sexual orientation. Further, it has been found that such therapies can lead to serious psychological outcomes for some people (Shidlo & Schroeder, 2002). As a result, in the United States, some states have banned such therapies through the legal system (Eckholm, 2013).

Like heterosexuals, gays and lesbians can be found in every occupation and at every socioeconomic level in our society. And, like heterosexuals, many gays and lesbians are involved in long-term, committed, and caring relationships (Roisman & others, 2008). Over 25 years of research suggests that children who are raised by gay or lesbian parents are as well adjusted as children who are raised by heterosexual parents (Perrin & others, 2013; Wainwright & Patterson, 2008). Finally, children who are raised by gay or lesbian parents are no more likely to be gay or lesbian in adulthood than are children who are raised by heterosexual parents (Anderssen & others, 2002; Bailey & others, 1995; Regnerus, 2012).

Question 10.12

mo98M1jz7up6OH323T5erfaNtReEd1uGhohYsB/rlRsSwfCNTx2WAG39USVz6vq4R7/pWBTrn3QgCS3S5XXqjvgWWN88O+80verz4H4ccNJ+2DkPlKg3NZwq2PoKRIvjpdcg9GJanB3Oh/387cdoJodkTT98AJfcRwpVNX7lRJDxj9HNevWkRVh94OJgivZKD9ipXTizp5cneX0I8ZV06Z3H02HaOljo0RmFk38lpE7hdMLIPLxBuqEo5ah1JWHHkVt1xaowVqeF4+1D6CQJvgWq1wA=CONCEPT REVIEW 10.2

Elements of Human Sexuality and Sexual Orientation

1. Justin is a 24-year-old heterosexual. His 20-year-old brother, Max, is gay. The brothers differ in their

| A. | gender roles |

| B. | gender identity |

| C. | sexual orientation |

| D. | gender schemas |

2. According to Masters and Johnson, the stages of the sexual response cycle are

| A. | plateau, excitement, and resolution in women and excitement, ejaculation, and resolution in men |

| B. | arousal, orgasm, and resolution, although the sequence can vary from one person or situation to another |

| C. | excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution in both men and women |

| D. | a buildup and release of testosterone in men and a similar buildup and release of estrogen in women |

3. After orgasm, males but not females experience

| A. | a refractory period |

| B. | a surge of testosterone |

| C. | a brief period of unconsciousness |

| D. | amnesia |

4. Which of the following statements accurately summarizes the research findings concerning biological factors and homosexuality?

| A. | Biological differences in the hypothalamus cause homosexuality. |

| B. | Sexual orientation is completely determined by genetics. |

| C. | Homosexuality is caused by insufficient amounts of testosterone. |

| D. | Some biological factors are correlated with homosexual orientation. |