12.2 Person Perception: FORMING IMPRESSIONS OF OTHER PEOPLE

KEY THEME

Person perception refers to the mental processes we use to form judgments about other people.

KEY QUESTIONS

What four principles are followed in the person perception process?

How do social categorization, implicit personality theories, and physical attractiveness affect person perception?

Consider the following scenario. You’re attending college in a big city and you commute from your apartment to campus via the subway. Today the subway is more than half full. If you want to sit down, you’ll have to share a seat with some other passenger. In a matter of seconds, you must decide which stranger you’ll share your ride home with, elbow to elbow, thigh to thigh. How will you decide?

Whether it’s a seat on the subway or in a crowded movie theater, this is a task that most of us confront almost every day: On the basis of very limited information, we must quickly draw conclusions about the nature and likely behavior of people who are complete strangers to us. How do we arrive at these conclusions?

Person perception refers to the mental processes we use to form judgments and draw conclusions about the characteristics of other people. Person perception is an active, subjective process that always occurs in some interpersonal context—that is, situations that involve interactions between two or more people (Macrae & Quadflieg, 2010; Smith & Collins, 2009).

person perception

The mental processes we use to form judgments and draw conclusions about the characteristics and motives of other people.

In the interpersonal context of a subway car, you evaluate people based on minimal interaction. You form very rapid first impressions largely by looking at other people’s faces, regardless of their actual personalities (Ames & others, 2009; Bar & others, 2006; Zebrowitz & Montepare, 2008). In a mere tenth of a second, you evaluate the other person’s attractiveness, likeability, competence, trustworthiness, and aggressiveness (Willis & Todorov, 2006).

Four key principles guide person perception and influence your decision (see Ambady & Skowronski, 2008; Zebrowitz & Montepare, 2006). Let’s illustrate those principles using the subway scenario.

Principle 1. Your reactions to others are determined by your perceptions of them, not by who they really are. On the subway, you quickly choose not to sit next to the big guy with a scowl on his face. Why? Because you perceive him as threatening. Of course, he could be a florist who’s surly because he’s getting home late.

Principle 2. Your self-perception also influences how you perceive others and how you act on your perceptions. Your decision about where to sit is also influenced by how you perceive yourself (Macrae & Quadflieg, 2010). For example, if you think of yourself as looking intimidating, you may not mind sitting next to the big guy with a scowl.

Principle 3. Your goals in a particular situation determine the amount and kinds of information you collect about others. If your goal is to share a subway seat with someone who will basically leave you alone, you will look for characteristics that are relevant to that goal—perhaps someone wearing telltale white earbuds who is obviously listening to music (Goodwin & others, 2002; Hilton, 1998).

Principle 4. In every situation, you evaluate people partly in terms of how you expect them to act within that particular context. Whether you’re in a classroom, restaurant, or public restroom, your behavior is governed by social norms—the unwritten “rules,” or expectations, for appropriate behavior in that particular social situation (Milgram, 1992). On the subway, for example, you don’t sit next to someone else when empty seats are available, and you don’t read your seatmate’s text messages. Violating these social norms will draw attention from others, as in the cartoon to the right!

social norms

The “rules,” or expectations, for appropriate behavior in a particular social situation.

What these four guiding principles demonstrate is that person perception is based on an interaction among four components: the perceptions we have of others, our self-perceptions, our goals, and the social norms for that context.

How does person perception play out in the online world of social media? Social psychologists have turned their attention to person perception in online contexts. For example, a Facebook profile photograph is more important than text in driving our perceptions. Even a comment about enjoying hanging out with a big group of friends doesn’t outweigh a photo depicting a loner on a park bench. This person would be perceived as introverted (Van Der Heide & others, 2012).

As another example, a person’s list of Facebook friends, part of the specific context in the Facebook environment, plays a role in how that person will be perceived. People are perceived to be more physically attractive if they have attractive Facebook friends (Antheunis & Schouten, 2011). And people are perceived as more socially attractive—that is, someone whom people would like to be friends with in the “real world”—if they have increasing numbers of Facebook friends (Tong & others, 2008). But this is true only up to about 300 “friends.” After that, perceptions of social attractiveness decrease perhaps because it doesn’t seem that all of these people are actually friends.

On a short subway ride, after a quick glance at a Facebook profile, or in other transient situations, you’ll probably never learn whether your first impressions were accurate or not. But first impressions are often wrong (Olivola & Todorov, 2010). And even if we have further encounters with a person, it takes a while for our impressions to change. Our first impression can color our overall impression of a person, something called the halo effect (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977). Initial information tends to create “a halo” around a person, and it becomes harder to notice new information that might conflict with the initial judgment. Thus, many professors grade work anonymously—they don’t want their previous impressions of you affecting their evaluation of your current work (Malouff & others, 2013). Fortunately, in situations that involve long-term relationships with other people, such as in a classroom or at work, we do start to fine-tune our impressions as we acquire additional information about the people we come to know (Smith & Collins, 2009).

Social Categorization: USING MENTAL SHORTCUTS IN PERSON PERCEPTION

Along with person perception, the subway scenario illustrates our natural tendency to group people into categories. Social categorization is the mental process of classifying people into groups on the basis of common characteristics.

social categorization

The mental process of categorizing people into groups (or social categories) on the basis of their shared characteristics.

So how do you socially categorize people who are complete strangers, such as the other passengers on the subway? To a certain extent, you consciously focus on easily observable features, such as the other person’s gender, age, or clothing (Kinzler & others, 2010; Miron & Branscomben, 2008). With a quick glance, you might socially categorize someone as “Asian male, 20-something, fraternity sweatshirt, probably a college student.” Social psychologists use the term explicit cognition to refer to these deliberate, conscious mental processes involved in perceptions, judgments, decisions, and reasoning.

explicit cognition

Deliberate, conscious mental processes involved in perceptions, judgments, decisions, and reasoning.

However, your social perceptions are not always completely conscious considerations. In many situations, you react to another person with automatic social perceptions, categorizations, and attitudes. Social psychologists use the term implicit cognition to describe the mental processes associated with automatic, nonconscious social evaluations (Gawronski & Payne, 2010).

implicit cognition

Automatic, nonconscious mental processes that influence perceptions, judgments, decisions, and reasoning.

Think Like a SCIENTIST

What factors in an online dating profile make you want to meet someone? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about Online Dating.

Prior experiences and beliefs about different social categories can trigger implicit social reactions ranging from very positive to very negative (Nosek & others, 2007). Without consciously realizing it, your reaction to another person can be swayed by characteristics such as ethnicity, weight, sexual orientation, or religious beliefs. There also may be evolutionary origins for our automatic reactions to others. For example, facial features perceived as attractive are similar across cultures (Chatterjee, 2011). And people of all ages tend to agree on facial attractiveness. Babies less than a week old spend more time looking at attractive faces than unattractive faces (Slater & others, 1998, 2010).

We often assume that certain types of people share certain traits and behaviors. This is referred to as an implicit personality theory. Different models exist to explain how implicit personality theories develop and function (see Critcher & Dunning, 2009; Ybarra, 2002). But in general terms, your previous social and cultural experiences influence the cognitive schemas, or mental frameworks, you hold about the traits and behaviors associated with different “types” of people. So when you perceive someone to be a particular “type,” you assume that the person will display those traits and behaviors (see Uleman & others, 2008).

implicit personality theory

A network of assumptions or beliefs about the relationships among various types of people, traits, and behaviors.

Physical appearance cues play an important role in person perception and social categorization (Olivola & Todorov, 2010). Particularly influential is the implicit personality theory that most people have for physically attractive people (see Anderson & others, 2008; Lemay & others, 2010). Starting in childhood, we are bombarded with the cultural message that “what is beautiful is good.” In myths, fairy tales, cartoons, movies, and games, heroes are handsome, heroines are beautiful, and the evil villains are ugly (Bazzini & others, 2010). As a result of such cultural conditioning, most people have an implicit personality theory that associates physical attractiveness with a wide range of desirable characteristics.

Decades of research have shown that good-looking people are perceived as being more intelligent, happier, and better adjusted than other people (Eagly & others, 1991; Lorenzo & others, 2010). In an extensive meta-analysis, Judith Langlois and her colleagues (2000) found that people tend to attribute a wide range of positive qualities to attractive individuals, viewing them as being more intelligent, strong, sensitive, honest, sociable, assertive, and emotionally stable. In addition to attractive people being perceived more positively, Genevieve Lorenzo and her colleagues (2010) found that they are also perceived more accurately, perhaps because people paid more attention to their traits. Lorenzo observed that “people do judge a book by its cover, but a beautiful cover prompts a closer reading” (2010).

But are beautiful people actually happier, smarter, or more successful than the rest of us? Economists Daniel Hamermesh and Jason Abrevya (2011) analyzed data from surveys conducted in four countries and concluded that more attractive people do tend to be happier, primarily because they also tended to have improved economic outcomes, such as higher salaries and more successful spouses.

Some studies have found that attractive people also tend to be higher in self-esteem, intelligence, and other desirable personality traits than people of more average appearance (Langlois & others, 2000; Sheppard & others, 2011). Why? One possibility is that, throughout their lives, they receive more favorable treatment from other people, such as parents, teachers, employers, and peers (Langlois & others, 1995; Sheppard & others, 2011). The attention that they receive may also be due to the positive emotional responses they evoke (Lemay & others, 2010). The Focus on Neuroscience below discusses evidence demonstrating that there may be a brain-based reason for the greater social success of beautiful people.

Obviously, the social categorization process has both advantages and disadvantages. Relegating someone to a social category on the basis of superficial information ignores that person’s unique qualities. Sometimes these conclusions are wrong, as Fern’s was when she categorized the scruffy-looking San Francisco man with a cup in his hand as homeless.

On the other hand, relying on social categories is a natural, adaptive, and efficient cognitive process. Social categories provide us with considerable basic information about other people. And from an evolutionary perspective, the ability to make rapid judgments about strangers is probably an evolved characteristic that conferred survival value in our evolutionary past.

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

Brain Reward When Making Eye Contact with Attractive People

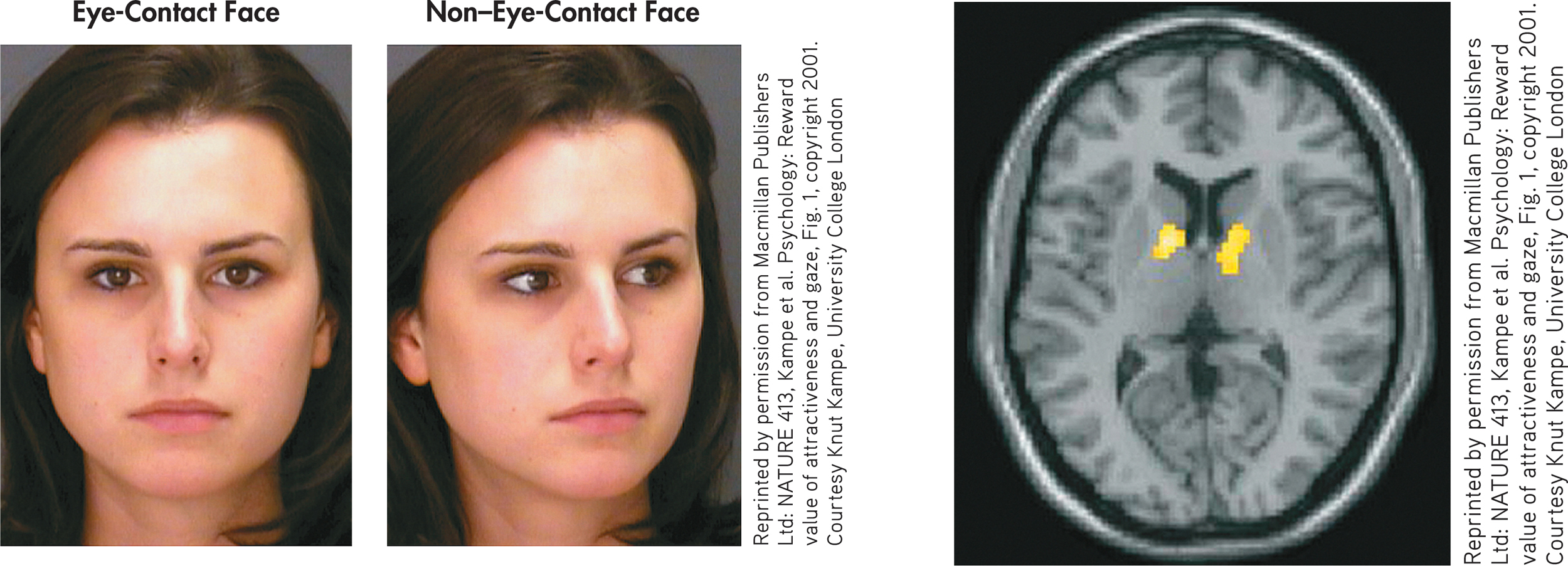

How does physical attractiveness contribute to social success? A study by neuroscientists Knut Kampe and his colleagues (2001) at University College London may offer some insights. In a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study, participants were scanned while they looked at color photographs of 40 different faces, some looking directly at the viewer (eye contact) and some glancing away (non–

The results showed that when we make direct eye contact with a physically attractive person, an area on each side of the brain called the ventral striatum is activated (yellow areas in fMRI scan). When the attractive person’s eye gaze is shifted away from the viewer, activity in the ventral striatum decreases. What makes this so interesting is that the ventral striatum is a brain area that predicts reward (Bray & O’Doherty, 2007). Neural activity in the ventral striatum increases when an unexpected reward, such as food or water, suddenly appears. Conversely, activity in the ventral striatum decreases when an expected reward fails to appear.

As Kampe (2001) explains, “What we’ve shown is that when we make eye contact with an attractive person, the brain area that predicts reward starts firing. If we see an attractive person but cannot make eye contact with that person, the activity in this region goes down, signaling disappointment. This is the first study to show that the brain’s ventral striatum processes rewards in the context of human social interaction.”

Other neuroscientists have identified additional brain reward areas that are responsive to facial attractiveness (see Chatterjee, 2011). Of particular note is the orbital frontal cortex, which is a region of the frontal cortex located just above the orbits (or sockets) of your eyes, and the nucleus accumbens, which is also associated with the brain’s reward system (Cloutier & others, 2008). Another region is the amygdala. The orbital frontal cortex, the nucleus accumbens, and the amygdala are all selectively responsive to the reward value of attractive faces (Chatterjee, 2011). This suggests that viewing attractive faces tends to activate many of the same brain areas that are involved in processing other types of pleasurable stimuli.

“Facial beauty evokes a widely distributed neural network involving perceptual, decision-making, and reward circuits. [It] may serve as a neural trigger for the pervasive effects of attractiveness in social interactions,” writes neuroscientist Anjan Chatterjee and his colleagues (2009). Apparently, the social advantages associated with facial attractiveness are reinforced by reward processing in the brain.

Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: NATURE 413, Kampe et al. Psychology: Reward value of attractiveness and gaze, Fig. 1, copyright 2001. Courtesy Knut Kampe, University College London