12.7 Obedience: JUST FOLLOWING ORDERS

The individual who is commanded by a legitimate authority ordinarily obeys. Obedience comes easily and often. It is a ubiquitous and indispensable feature of social life.

—Stanley Milgram (1963)

KEY THEME

Stanley Milgram conducted a series of controversial studies on obedience, which is behavior performed in direct response to the orders of an authority.

KEY QUESTIONS

What were the results of Milgram’s original obedience experiments?

What experimental factors were shown to increase the level of obedience?

What experimental factors were shown to decrease the level of obedience?

Stanley Milgram was one of the most creative and influential researchers that social psychology has known (Blass, 2004, 2009; A. G. Miller, 2009). He is best known for his experimental investigations of obedience. Obedience is the performance of a behavior in response to a direct command. Typically, an authority figure or a person of higher status, such as a teacher or supervisor, gives the command.

obedience

The performance of a behavior in response to a direct command.

Milgram was intrigued by Asch’s discovery of how easily people could be swayed by group pressure. But Milgram wanted to investigate behavior that had greater personal significance than simply judging line lengths on a card (Milgram, 1963). Thus, Milgram posed what he saw as the most critical question: Could a person be pressured by others into committing an immoral act, some action that violated his or her own conscience, such as hurting a stranger? In his efforts to answer that question, Milgram embarked on one of the most systematic and controversial investigations in the history of psychology: to determine how and why people obey the destructive dictates of an authority figure (Blass, 2009; Russell, 2011).

Milgram’s Original Obedience Experiment

Milgram was only 28 years old and a new faculty member at Yale University when he conducted his first obedience experiments. He recruited participants through direct-mail solicitations and ads in the local paper. Milgram’s subjects represented a wide range of occupational and educational backgrounds. Postal workers, high school teachers, white-collar workers, engineers, and laborers participated in the study.

Outwardly, it appeared that two subjects showed up at Yale University to participate in the psychology experiment, but the second subject was actually an accomplice working with Milgram. The role of the experimenter, complete with white lab coat, was played by a high school biology teacher. When both subjects arrived, the experimenter greeted them and gave them a plausible explanation of the study’s purpose: to examine the effects of punishment on learning.

Both subjects drew slips of paper to determine who would be the “teacher” and who the “learner.” However, the drawing was rigged so that the real subject was always the teacher and the accomplice was always the learner. The learner was actually a mild-mannered, 47-year-old accountant who had been carefully rehearsed for his part in the drama. Assigned to the role of the teacher, the real subject would be responsible for “punishing” the learner’s mistakes by administering electric shocks.

Immediately after the drawing, the teacher and learner were taken to another room, where the learner was strapped into an “electric chair.” The teacher was then taken to a different room, from which he could hear but not see the learner. Speaking into a microphone, the teacher tested the learner on a simple word-pair memory task. In the other room, the learner pressed one of four switches to indicate with which alternative the word had previously been paired. The learner’s response was registered in an answer box positioned on top of the “shock generator” in front of the teacher. Each time the learner answered incorrectly, the teacher was to deliver an electric shock.

Just in case there was any lingering doubt in the teacher’s mind about the legitimacy of the shock generator, the teacher was given a sample jolt using the switch marked 45 volts. In fact, this sample shock was the only real shock given during the course of the staged experiment.

The first time the learner answered incorrectly, the teacher was to deliver an electric shock at the 15-volt level. With each subsequent error, the teacher was told to progress to the next level on the shock generator. The teacher was also told to announce the voltage level to the learner before delivering the shock.

At predetermined voltage levels, the learner vocalized first his discomfort, then his pain, and, finally, agonized screams. Some of the learner’s vocalizations at the different voltage levels are shown in TABLE 12.3. After 330 volts, the learner’s script called for him to fall silent. If the teacher protested that he wished to stop or that he was worried about the learner’s safety, the experimenter would say, “The experiment requires that you continue” or “You have no other choice, you must continue.”

The Learner’s Schedule of Protests in Milgram’s Obedience Experiment

| 120 volts | → | Ugh! Hey, this really hurts. |

| 150 volts | → | Ugh!!! Experimenter! That’s all. Get me out of here. I told you I had heart trouble. My heart’s starting to bother me now. Get me out of here, please. My heart’s starting to bother me. I refuse to go on. Let me out. |

| 210 volts | → | Ugh!! Experimenter! Get me out of here. I’ve had enough. I won’t be in the experiment any more. |

| 270 volts | → | (Agonized scream.) Let me out of here. Let me out of here. Let me out of here. Let me out. Do you hear? Let me out of here. |

| 300 volts | → | (Agonized scream.) I absolutely refuse to answer any more. Get me out of here. You can’t hold me here. Get me out. Get me out of here. |

| 315 volts | → | (Intensely agonized scream.) I told you I refuse to answer. I’m no longer part of this experiment. |

| 330 volts | → | (Intense and prolonged agonized scream.) Let me out of here. Let me out of here. My heart’s bothering me. Let me out, I tell you. (Hysterically) Let me out of here. Let me out of here. You have no right to hold me here. Let me out! Let me out! Let me out! Let me out of here! Let me out! Let me out! |

| This table shows examples of the learner’s protests at different voltage levels. If the teacher administered shocks beyond the 330-volt level, the learner’s agonized screams were replaced with an ominous silence. Source: Milgram (1974a). | ||

According to the script, the experiment would be halted when the teacher refused to obey the experimenter’s orders to continue. Alternatively, if the teacher obeyed the experimenter, the experiment would be halted once the teacher had progressed all the way to the maximum shock level of 450 volts.

Either way, after the experiment, the teacher was interviewed and it was explained that the learner had not actually received dangerous electric shocks. To underscore this point, a “friendly reconciliation” was arranged between the teacher and the learner, and the true purpose of the study was explained to the subject.

The Results of Milgram’s Original Experiment

Can you predict how Milgram’s subjects behaved? Of the 40 subjects, how many obeyed the experimenter and went to the full 450-volt level? On a more personal level, how do you think you would have behaved had you been one of Milgram’s subjects?

MYTH !lhtriangle! SCIENCE

Is it true that most people will not harm another person if ordered to do so?

Milgram himself asked psychiatrists, college students, and middle-class adults to predict how subjects would behave (see Milgram, 1974a). All three groups predicted that all of Milgram’s subjects would refuse to obey at some point. They predicted that most subjects would refuse at the 150-volt level, the point at which the learner first protested. They also believed that only a few rare individuals would go as far as the 300-volt level. Finally, none of those surveyed thought that any of Milgram’s subjects would go to the full 450 volts.

As it turned out, they were all wrong. Two-thirds of Milgram’s subjects—26 of the 40—were fully compliant and went to the full 450-volt level. And of those who defied the experimenter, not one stopped before the 300-volt level. TABLE 12.4 below shows the results of Milgram’s original obedience study.

The Results of Milgram’s Original Study

| Shock Level | Switch Labels and Voltage Levels | Number of Subjects Who Refused to Administer a Higher Voltage Level |

|---|---|---|

| Slight Shock | ||

| 1 | 15 | |

| 2 | 30 | |

| 3 | 45 | |

| 4 | 60 | |

| Moderate Shock | ||

| 5 | 75 | |

| 6 | 90 | |

| 7 | 105 | |

| 8 | 120 | |

| 9 | 135 | |

| 10 | 150 | |

| 11 | 165 | |

| 12 | 180 | |

| Very Strong Shock | ||

| 13 | 195 | |

| 14 | 210 | |

| 15 | 225 | |

| 16 | 240 | |

| Intense Shock | ||

| 17 | 255 | |

| 18 | 270 | |

| 19 | 285 | |

| 20 | 300 | |

| Extreme Intensity Shock | ||

| 21 | 315 | 5 |

| 22 | 330 | |

| 23 | 345 | 4 |

| 24 | 360 | 2 |

| Danger: Severe Shock | 1 | |

| 25 | 375 | 1 |

| 26 | 390 | |

| 27 | 405 | 1 |

| 28 | 420 | |

| XXX | ||

| 29 | 435 | |

| 30 | 450 | 26 |

| Source: Data from Milgram (1974a). | ||

| Contrary to what psychiatrists, college students, and middle-class adults predicted, the majority of Milgram’s subjects did not refuse to obey by the 150-volt level of shock. As this table shows, 14 of Milgram’s 40 subjects (35 percent) refused to continue at some point after administering 300 volts to the learner. However, 26 of the 40 subjects (65 percent) remained obedient to the very end, administering the full 450 volts to the learner. | ||

Surprised? Milgram himself was stunned by the results, never expecting that the majority of subjects would administer the maximum voltage. Were his results a fluke? Did Milgram inadvertently assemble a sadistic group of New Haven residents who were all too willing to inflict extremely painful, even life-threatening, shocks on a complete stranger?

The answer to both these questions is no. Milgram’s obedience study has been repeated many times in the United States and other countries (see Blass, 2000, 2012). And, in fact, Milgram (1974a) replicated his own study on numerous occasions, using variations of his basic experimental procedure.

In one replication, for instance, Milgram’s subjects were 40 women. Were female subjects any less likely to inflict pain on a stranger? Not at all. The results were identical. Confirming Milgram’s results since then, eight other studies also found no sex differences in obedience to an authority figure (see Blass, 2000, 2004; Burger, 2009).

Perhaps Milgram’s subjects saw through his elaborate experimental hoax, as some critics have suggested (Orne & Holland, 1968). Was it possible that the subjects did not believe that they were really harming the learner? Again, the answer seems to be no. Milgram’s subjects seemed totally convinced that the situation was authentic. And they did not behave in a cold-blooded, unfeeling way. Far from it. As the experiment progressed, many subjects showed signs of extreme tension and conflict.

In describing the reaction of one subject, Milgram (1963) wrote, “I observed a mature and initially poised businessman enter the laboratory smiling and confident. Within 20 minutes he was reduced to a twitching, stuttering wreck, who was rapidly approaching a point of nervous collapse.” Extreme reactions like this one have led people to question the ethics of Milgram’s experiment (Perry, 2013).

Making Sense of Milgram’s Findings: MULTIPLE INFLUENCES

Milgram, along with other researchers, identified several aspects of the experimental situation that had a strong impact on the subjects (see Blass, 1992, 2000; Milgram, 1965). Here are some of the forces that influenced subjects to continue obeying the experimenter’s orders:

A previously well-established mental framework to obey. Having volunteered to participate in a psychology experiment, Milgram’s subjects arrived at the lab with the mental expectation that they would obediently follow the directions of the person in charge—the experimenter. They also accepted compensation on their arrival, which may have increased their sense of having made a commitment to cooperate with the experimenter.

The situation, or context, in which the obedience occurred. The subjects were familiar with the basic nature of scientific investigation, believed that scientific research was worthwhile, and were told that the goal of the experiment was to “advance the scientific understanding of learning and memory” (Milgram, 1974a). All these factors predisposed the subjects to trust and respect the experimenter’s authority (Darley, 1992). Even when subjects protested, they were polite and respectful. Milgram suggested that subjects were afraid that defying the experimenter’s orders would make them appear arrogant, rude, disrespectful, or uncooperative.

The gradual, repetitive escalation of the task. At the beginning of the experiment, the subject administered a very low level of shock—15 volts. Subjects could easily justify using such low levels of electric shock in the service of science. The shocks, like the learner’s protests, escalated only gradually.

The experimenter’s behavior and reassurances. Many subjects asked the experimenter who was responsible for what might happen to the learner. In every case, the teacher was reassured that the experimenter was responsible for the learner’s well-being. Thus, the subjects could believe that they were not responsible for the consequences of their actions. They could tell themselves that their behavior must be appropriate if the experimenter approved of it.

The physical and psychological separation from the learner. Several “buffers” distanced the subject from the pain that he was inflicting on the learner. First, the learner was in a separate room and not visible. Only his voice could be heard. Second, punishment was depersonalized: The subject simply pushed a switch on the shock generator. Finally, the learner never appealed directly to the teacher to stop shocking him. The learner’s pleas were always directed toward the experimenter, as in “Experimenter! Get me out of here!” Undoubtedly, this contributed to the subject’s sense that the experimenter, rather than the subject, was ultimately in control of the situation, including the teacher’s behavior. Overall, Milgram demonstrated that the rate of obedience rose or fell depending upon the situational variables the subjects experienced (Zimbardo, 2007).

Confidence that the learner was actually receiving shocks. There is evidence suggesting that at least some of Milgram’s subjects suspected that the learner was not receiving shocks. Milgram (1965) reported that only 56.1% of subjects “fully believed the learner was getting painful shocks.” Others had doubts to varying degrees, with 13.6% either feeling that the learner was probably not getting shocked or feeling certain that the learner was not getting shocked. And as doubts increased, the likelihood of obeying also increased. Conversely, those most confident that the learner was actually receiving shocks were less likely to obey. Psychologist Gina Perry (2013) spent several years immersing herself in the archives at Yale and interviewing many researchers and subjects associated with Milgram’s studies. She discovered unpublished data, compiled by Milgram’s research assistant, Taketo Murata, that supported Milgram’s report. Across the 23 variations of Milgram’s experiments, Murata found that subjects were more likely to disobey if they believed the learner was actually receiving shocks.

Question 12.17

KPExk6e8XJPcu0aqv6BgB7rzRA2eaQhAkPqdxYbIcTkU9qE+m3lwS6ghijfa1iRmBk5+QRo2z1D94FrOCJ3mwF2KHKc7aN9N3l4Z6OcNXCPi263Y1yKwuQmq8AsFuvHCQNysLPbLVU4QHylJr2Vij6lcjgolMtyiWSugGgKCMu+oLnXmmvPRJ/uaLu6Z553OCvafptadPaDKqQNacHEa4ArPg6EiEqqhzK0iydyOszJTqRBPEIduY1ViaJAvO/3xWvR7xdtYPO3pF++JyHlcfc7spEpzT5QBiqA0HseNjVfQqvCWtmW7c8TjNv8=Conditions That Undermine Obedience: VARIATIONS ON A THEME

In a lengthy series of experiments, Milgram systematically varied the basic obedience paradigm. To give you some sense of the enormity of Milgram’s undertaking, approximately 1,000 subjects, each tested individually, experienced some variation of Milgram’s obedience experiment. Thus, Milgram’s obedience research represents one of the largest and most integrated research programs in social psychology (Blass, 2000).

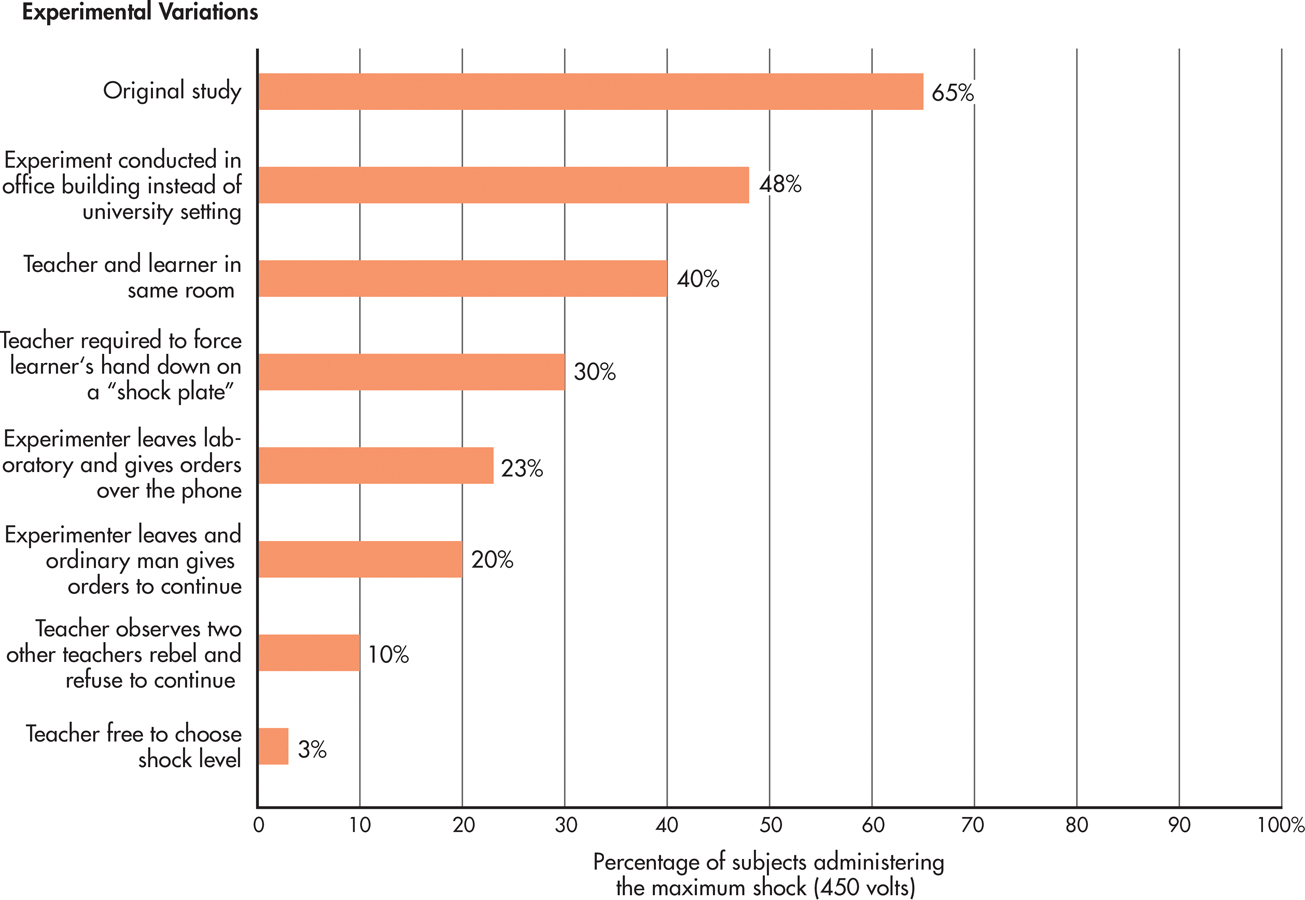

By varying his experiments, Milgram identified several conditions that decreased the likelihood of destructive obedience, which are summarized in FIGURE 12.4. For example, willingness to obey diminished sharply when the buffers that separated the teacher from the learner were lessened or removed, such as when both of them were in the same room.

If Milgram’s findings seem to cast an unfavorable light on human nature, there are two reasons to take heart. First, when teachers were allowed to act as their own authority and freely choose the shock level, 95 percent of them did not venture beyond 150 volts—the first point at which the learner protested. Clearly, Milgram’s subjects were not responding to their own aggressive or sadistic impulses, but rather to orders from an authority figure (see Reeder & others, 2008).

Second, Milgram found that people were more likely to muster up the courage to defy an authority when they saw others do so. When Milgram’s subjects observed what they thought were two other subjects disobeying the experimenter, the real subjects followed their lead 90 percent of the time and refused to continue. Like the subjects in Asch’s experiment, Milgram’s subjects were more likely to stand by their convictions when they were not alone in expressing them. Despite these encouraging notes, the overall results of Milgram’s obedience research painted a bleak picture of human nature.

Many people wonder whether Milgram would get the same results if his experiments were repeated today. Are people still as likely to obey an authority figure? There have been several replications or partial replications in recent years, including one by psychologist Jerry Burger and several by entertainment or news media including on the Discovery Channel show Curiosity, a BBC documentary, and DatelineNBC (BBC News, 2008; Burger, 2009; Lowry, 2011; Perry, 2013).

In one example, using methods similar to Milgram’s, French researchers found high levels of obedience in a game-show setting in a TV studio where participants obeyed a television host (Beauvois & others, 2012). In the show, called Game of Death, the researchers used all the trappings of a television production to convince participants that the situation was real—a glamorous and well-known host, professional cameras, spotlights, a comedian to warm up the audience, and a live audience naïve to the actual goal of the situation.

The researchers recruited 76 participants from Paris, having excluded anyone who was aware of Milgram’s research. Participants were asked to shock another “contestant” every time he answered a question incorrectly. (As in Milgram’s study, the “contestant” was an actor who was not actually receiving shocks.) The game show host used prompts similar to those used by Milgram’s experimenter, and she had an added encouragement available to her—having the audience intervene. The researchers explained that “in power-based and situation-based terms, the host-questioner rapport in the present study was very close to the researcher-professor situation in Milgram’s study” (Beauvois & others, 2012).

So, what do you think happened? Eighty-one percent of participants obeyed, a figure higher than, although not statistically different from, Milgram’s findings. Importantly, unlike in Milgram’s era, there was an immediate international outcry about the ethics of putting unwitting participants in such a situation.

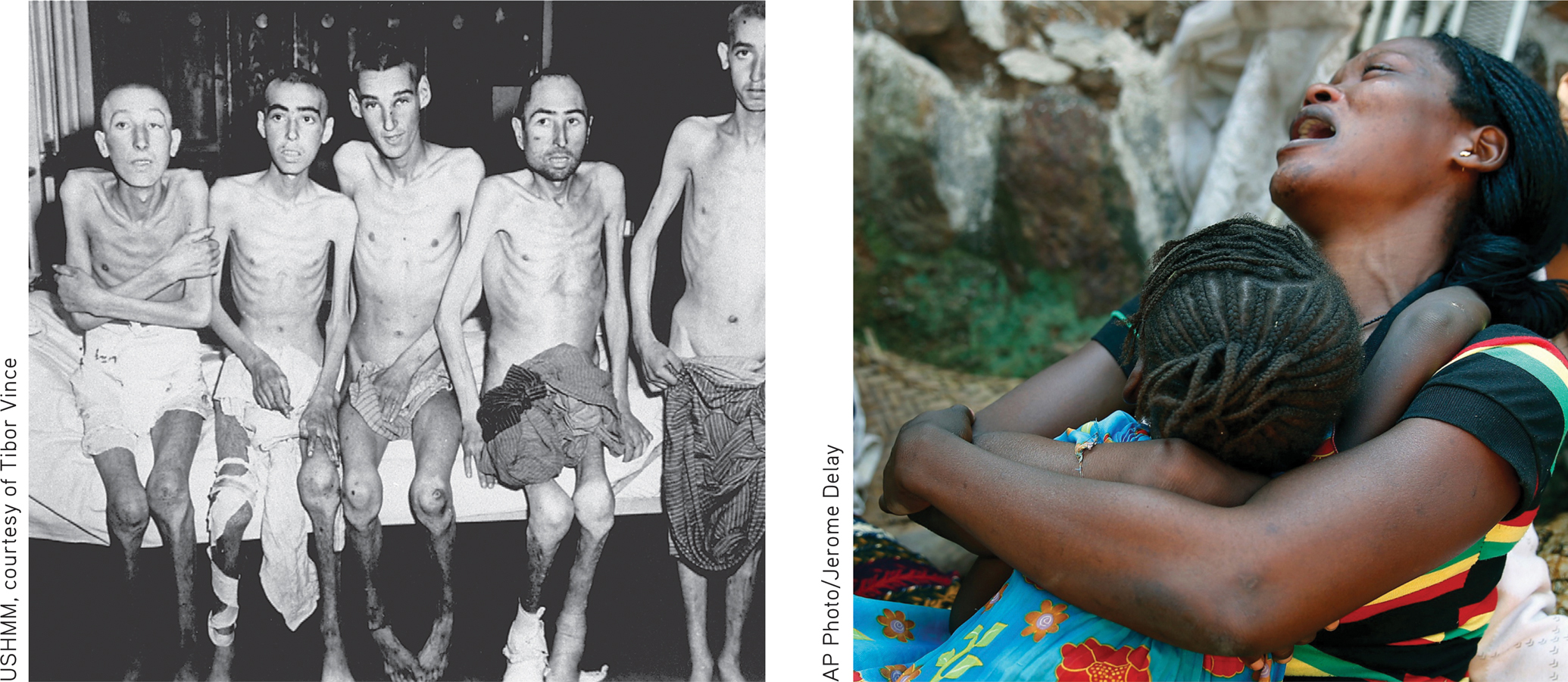

More than 40 years after the publication of Milgram’s research, the moral issues that his findings highlighted are still with us. Should military personnel be prosecuted for obeying orders to commit an immoral or illegal act? Who should be held responsible? We discuss a contemporary instance of destructive obedience in the Critical Thinking box below, “Abuse at Abu Ghraib: Why Do Ordinary People Commit Evil Acts?”

Asch, Milgram, and the Real World: IMPLICATIONS OF THE CLASSIC SOCIAL INFLUENCE STUDIES

The scientific study of conformity and obedience has produced some important insights. The first is the degree to which our behavior is influenced by situational factors (see Benjamin & Simpson, 2009; Zimbardo, 2007). Being at odds with the majority or with authority figures is very uncomfortable for most people—enough so that our judgment and perceptions can be distorted and we may act in ways that violate our conscience.

AP Photo/Jerome Delay

More important, perhaps, is the insight that each of us does have the capacity to resist group or authority pressure (Bocchiaro & Zimbardo, 2010). Because the central findings of these studies are so dramatic, it’s easy to overlook the fact that some subjects refused to conform or obey despite considerable social and situational pressure (Packer, 2008a). Consider the response of a subject in one of Milgram’s later studies (Milgram, 1974a). A 32-year-old industrial engineer named Jan Rensaleer protested when he was commanded to continue at the 255-volt level:

CRITICAL THINKING

Abuse at Abu Ghraib: Why Do Ordinary People Commit Evil Acts?

When the first Abu Ghraib photos appeared, people around the world were shocked. The photos graphically depicted Iraqi prisoners being humiliated, abused, and beaten by U.S. military personnel at Abu Ghraib prison near Baghdad. In one photo, an Iraqi prisoner stood naked with feces smeared on his face and body. A hooded prisoner stood on a box with wires dangling from his outstretched arms. Smiling American soldiers, both male and female, posed alongside the corpse of a beaten Iraqi prisoner, giving the thumbs-up sign for the camera.

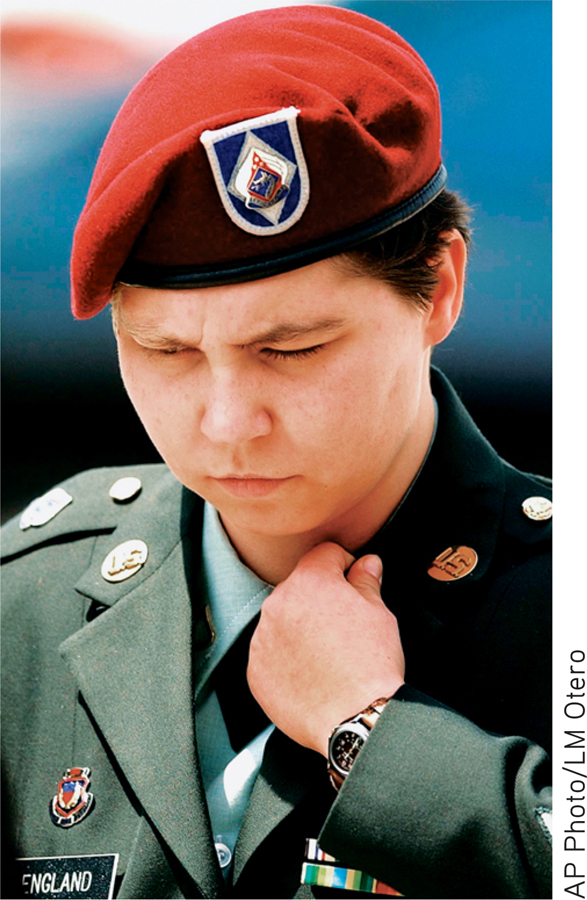

In the international uproar that followed, U.S. political leaders and Defense Department officials scrambled, damage control at the top of their lists. “A few bad apples” was the official pronouncement—just isolated incidents of overzealous or sadistic soldiers run amok. The few “bad apples” were identified and arrested: nine members of an Army Reserve unit that was based in Cresaptown, Maryland.

Why would ordinary Americans mistreat people like that? How can normal people commit such cruel, immoral acts?

Unless we learn the dynamics of “why,” we will never be able to counteract the powerful forces that can transform ordinary people into evil perpetrators.

—Philip Zimbardo, (2004b)

What actually happened at Abu Ghraib?

At its peak population in early 2004, the Abu Ghraib prison complex housed more than 6,000 Iraqis who had been detained during the American invasion and occupation of Iraq. The detainees ranged from petty thieves and other criminals to armed insurgents to those who simply seemed to have been in the wrong place at the wrong time (James, 2008).

There had been numerous reports that prisoners were being mistreated at Abu Ghraib, including official complaints by the International Red Cross. However, most Americans had no knowledge of the prison conditions until photographs documenting shocking incidents of abuse were shown on national television and featured in the New Yorker magazine (Hersh, 2004a, 2004b).

What factors contributed to the events that occurred at Abu Ghraib prison?

Multiple elements combined to create the conditions for brutality, including in-group versus out-group thinking, negative stereotypes, dehumanization, and prejudice. The Iraqi prisoners were of a different culture, ethnic group, and religion than the prison guards, none of whom spoke Arabic. Categorizing the prisoners as a dangerous and threatening outgroup allowed the American guards to dehumanize the detainees, who were seen as subhuman (Fiske & others, 2004).

The worst incidents took place in a cell block that held the prisoners who were thought to be most dangerous and who had been identified as potential “terrorists” or “insurgents” (Hersh, 2005). The guards were led to believe that it was their duty to mistreat these potential terrorists in order to help extract useful information (Taguba, 2004). In this way, aggression was transformed from being inexcusable and inhumane into a virtuous act of patriotism (Kelman, 2005; Post, 2011). Thinking in this way also helped reduce any cognitive dissonance the soldiers might have been experiencing by justifying the aggression.

Is what happened at Abu Ghraib similar to what happened in Milgram’s studies?

Milgram’s controversial studies showed that even ordinary citizens will obey an authority figure and commit acts of destructive obedience. Some of the accused soldiers, like Army Reserve Private Lynndie England, did claim that they were “just following orders.” Photographs of England, a file clerk from West Virginia, with naked prisoners, especially the one in which she was holding a naked male prisoner on a leash, created international outrage and revulsion. But England (2004) testified that her superiors praised the photos and told her, “Hey, you’re doing great, keep it up.”

But were the guards “just following orders”?

During the investigation and court-martials, soldiers who were called as witnesses for the prosecution testified that no direct orders were given to abuse or mistreat any prisoners (Zernike, 2004). However, as a classic and controversial experiment by Stanford University psychologist Philip Zimbardo and his colleagues (1973) showed, implied social norms and roles can be just as powerful as explicit orders.

A study known as the Stanford Prison Experiment was conducted in 1971 (Haney & others, 1973). Twenty-four male college students were randomly assigned to be either prisoners or prison guards. They played their roles in a makeshift but realistic prison that had been set up in the basement of a Stanford University building. All of the participants had been evaluated and judged to be psychologically healthy, well-adjusted individuals.

Originally, the experiment was slated to run for two weeks. But after just six days, the situation was spinning out of control. As Zimbardo (2005) recalls, “Within a few days, [those] assigned to the guard role became abusive, red-necked prison guards…. Within 36 hours the first prisoner had an emotional breakdown, crying, screaming, and thinking irrationally.” In all, five participants had emotional breakdowns (Drury & others, 2012). Prisoners who did not have extreme stress reactions became passive and depressed.

The value of the Stanford Prison Experiment resides in demonstrating the evil that good people can be readily induced into doing to other good people within the context of socially approved roles, rules, and norms …

—Philip Zimbardo, 2000a

While Milgram’s experiments showed the effects of direct authority pressure, the Stanford Prison Experiment demonstrated the powerful influence of situational roles and conformity to implied social rules and norms. These influences are especially pronounced in vague or novel situations where normative social influence is more likely (Zimbardo, 2007). When people are not certain what to do, they tend to rely on cues provided by others and to conform their behavior to that of those in their immediate group (Fiske & others, 2004).

At Abu Ghraib, the accused soldiers received no special training and were ignorant of either international or Army regulations regarding the treatment of civilian detainees or enemy prisoners of war (see James, 2008; Zimbardo, 2007). In the chaotic cell block, the guards apparently took their cues from one another and from the military intelligence personnel who encouraged them to “set the conditions” for interrogation (Hersh, 2005; Taguba, 2004).

Are people helpless to resist destructive obedience in a situation like Abu Ghraib prison?

No. As Milgram demonstrated, people can and do resist pressure to perform evil actions. Not all military personnel at Abu Ghraib went along with the pressure to mistreat prisoners (Hersh, 2005; Taguba, 2004). Consider these examples:

Master-at-Arms William J. Kimbro, a Navy dog handler, adamantly refused to participate in improper interrogations using dogs to intimidate prisoners despite being pressured by military intelligence personnel (Hersh, 2004b).

When handed a CD filled with digital photographs depicting prisoners being abused and humiliated, Specialist Joseph M. Darby turned it over to the Army Criminal Investigation Division. It was Darby’s conscientious action that finally prompted a formal investigation of the prison.

At the courts-martial, army personnel called as prosecution witnesses testified that the abusive treatment shown in the photographs would never be allowed under any stretch of the normal rules for handling inmates in a military prison (Zernike, 2004).

In fact, as General Peter Pace, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, stated forcefully in a November 2005 press conference, “It is absolutely the responsibility of every U.S. service member, if they see inhumane treatment being conducted, to intervene to stop it.”

Finally, it’s important to point out that understanding the factors that contributed to the events at Abu Ghraib does not excuse the perpetrators’ behavior or absolve them of individual responsibility. And, as Milgram’s research shows, the action of even one outspoken dissenter can inspire others to resist unethical or illegal commands from an authority figure (Packer, 2008a).

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

How might the fundamental attribution error lead people to blame “a few bad apples” rather than noticing situational factors that contributed to the Abu Ghraib prison abuse?

Who should be held responsible for the inhumane conditions and abuse that occurred at Abu Ghraib prison?

Experimenter: It is absolutely essential that you continue.

Mr. Rensaleer: Well, I won’t—not with the man screaming to get out.

Experimenter: You have no other choice.

Mr. Rensaleer: I do have a choice. (Incredulous and indignant) Why don’t I have a choice? I came here on my own free will. I thought I could help in a research project. But if I have to hurt somebody to do that, or if I was in his place, too, I wouldn’t stay there. I can’t continue. I’m very sorry. I think I’ve gone too far already, probably.

Like some of the other participants in the obedience and conformity studies, Rensaleer effectively resisted the situational and social pressures that pushed him to obey. As did Army Sergeant Joseph M. Darby, who triggered the investigation of abuses at the Abu Ghraib prison camp in Iraq by turning over a CD with photos of the abuse to authorities. As Darby said, the photos “violated everything that I personally believed in and everything that I had been taught about the rules of war.” Another man who took a stand, stopping and then reporting an abusive incident in the prison, was 1st Lieutenant David Sutton. As he put it, “The way I look at it, if I don’t do something, I’m just as guilty.” TABLE 12.5 summarizes several strategies that can help people resist the pressure to conform or obey in a destructive, dangerous, or morally questionable situation.

Resisting an Authority’s Unacceptable Orders

|

Verify your own discomfort by asking yourself, “Is this something I would do if I were controlling the situation?” Express your discomfort. It can be as simple as saying, “I’m really not comfortable with this.” Resist even slightly objectionable commands so that the situation doesn’t escalate into increasingly immoral or destructive obedience. If you realize you’ve already done something unacceptable, stop at that point rather than continuing to comply. Find or create an excuse to get out of the situation and validate your concerns with someone who is not involved with the situation. Question the legitimacy of the authority. Most authorities have legitimacy only in specific situations. If authorities are out of their legitimate context, they have no more authority in the situation than you do. If it is a group situation, find an ally who also feels uncomfortable with the authority’s orders. Two people expressing dissent in harmony can effectively resist conforming to the group’s actions. |

| Sources: Information from American Psychological Association, 2005b; Asch, 1956, 1957; Blass, 1991, 2004; Haney & others, 1973; Milgram, 1963, 1974a; Zimbardo, 2000a, 2004a, 2007. |

How are such people different from those who conform or obey? Unfortunately, there’s no satisfying answer to that question. No specific personality trait consistently predicts conformity or obedience in experimental situations such as those Asch and Milgram created (see Blass, 2000, 2004; Burger, 2009). In other words, the social influences that Asch and Milgram created in their experimental situations can be compelling even to people who are normally quite independent.

Finally, we need to emphasize that conformity and obedience are not completely bad in and of themselves. Quite the contrary. Conformity and obedience are necessary for an orderly society, which is why such behaviors were instilled in all of us as children. The critical issue is not so much whether people conform or obey, because we all do so every day of our lives. Rather, the critical issue is whether the norms we conform to, or the orders we obey, reflect values that respect the rights, well-being, and dignity of others.

Test your understanding of Factors Influencing Conformity and Obedience with

.

.