13.4 Coping: HOW PEOPLE DEAL WITH STRESS

KEY THEME

Coping refers to the ways in which we try to change circumstances, or our interpretation of circumstances, to make them less threatening.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the two basic forms of coping, and when is each form typically used?

What are some of the most common coping strategies?

How does culture affect coping style?

Think about some of the stressful periods that have occurred in your life. What kinds of strategies did you use to deal with those distressing events? Which strategies seemed to work best? Did any of the strategies end up working against your ability to reduce the stressor? If you had to deal with the same events again today, would you do anything differently?

For example, imagine that you discovered that you weren’t allowed to register for classes because the financial aid office had lost your paperwork. How would you react? What would you do?

The strategies that you use to deal with distressing events are examples of coping. Coping refers to the ways in which we try to change circumstances, or our interpretation of circumstances, to make them more favorable and less threatening (Folkman, 2009).

coping

Behavioral and cognitive responses used to deal with stressors; involves our efforts to change circumstances, or our interpretation of circumstances, to make them more favorable and less threatening.

Adaptive coping is a dynamic and complex process (Carver, 2011). We may switch our coping strategies as we appraise the changing demands of a stressful situation and our available resources at any given moment. We also evaluate whether our efforts have made a stressful situation better or worse and adjust our coping strategies accordingly.

When coping is effective, we adapt to the situation and stress is reduced. Unfortunately, coping efforts do not always help us adapt. Maladaptive coping can involve thoughts and behaviors that intensify or prolong distress, or that produce self-defeating outcomes (Thompson & others, 2010). The rejected lover who continually dwells on his former companion, passing up opportunities to form new relationships and letting his studies slide, is demonstrating maladaptive coping.

Adaptive coping responses serve many functions (Folkman, 2009; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2007). Most important, adaptive coping involves realistically evaluating the situation and determining what can be done to minimize the impact of the stressor. But adaptive coping also involves dealing with the emotional aspects of the situation. In other words, adaptive coping often includes developing emotional tolerance for negative life events, maintaining self-esteem, and keeping emotions in balance. Finally, adaptive coping efforts are directed toward preserving important relationships.

Traditionally, coping has been broken down into two major categories—problem-focused and emotion-focused (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004). As you’ll see in the next sections, each type of coping serves a different purpose. However, people are flexible in the coping styles they adopt, often relying on different coping strategies for different stressors (Kammeyer-Mueller & others, 2009).

Problem-Focused Coping Strategies: CHANGING THE STRESSOR

Problem-focused coping is aimed at managing or changing a threatening or harmful stressor. Problem-focused coping strategies tend to be most effective when you can exercise some control over the stressful situation or circumstances (Kammeyer-Mueller & others, 2009; Park & others, 2004).

problem-focused coping

Coping efforts primarily aimed at directly changing or managing a threatening or harmful stressor.

Our friend Wyncia, whose own house narrowly escaped the flames, demonstrated the value of problem-focused coping. A member of the volunteer fire department, she received the call to mobilize just minutes after she saw the thick cloud of black smoke and realized that the fire was nearby. Grabbing her emergency kit, Wyncia raced to the fire station, leaving her husband to pack up their dog and whatever else he could hurriedly stuff into their car as the flames drew near.

Wyncia said, “When you experience that gut ‘fight-or-flight reaction,’ and there’s no one to fight, and nowhere to run, you just melt down. But when you’re with the fire department, instead of melting down, you get up and do your job. Joining the fire department as a volunteer was the best thing I could have done. Instead of just sitting at the bottom of the hill and waiting for news, and looking at the horrible smoke and wondering whether my house was still there, I was actually involved with the people who were working on the problem. I was doing something about it.”

Planful problem solving involves efforts to rationally analyze the situation, identify potential solutions, and then implement them. In effect, you take the attitude that the stressor represents a problem to be solved. Once you assume that mental stance, you follow the basic steps of problem solving (see Chapter 7).

When people tackle a problem head on, they are engaging in confrontive coping. Ideally, confrontive coping is direct and assertive but not hostile or angry. When it is hostile or aggressive, confrontive coping may well generate negative emotions in the people being confronted, damaging future relations with them (Folkman & Lazarus, 1991). However, if you recall our earlier discussion of hostility, then you won’t be surprised to find that hostile individuals often engage in confrontive coping (Vandervoort, 2006).

Emotion-Focused Coping Strategies: CHANGING YOUR REACTION TO THE STRESSOR

When the stressor is one over which we can exert little or no control, we often focus on the dimension of the situation that we can control—the emotional impact of the stressor on us. When people think that nothing can be done to alter a situation, they tend to rely on emotion-focused coping. They direct their efforts toward relieving or regulating the emotional impact of the stressful situation (Scott & others, 2010). Although emotion-focused coping doesn’t change the problem, it can help you feel better about it.

emotion-focused coping

Coping efforts primarily aimed at relieving or regulating the emotional impact of a stressful situation.

When you shift your attention away from the stressor and toward other activities, you’re engaging in the emotion-focused coping strategy called escape–

Because you are focusing your attention on something other than the stressor, escape–

In the long run, escape–

Seeking social support is the coping strategy that involves turning to friends, relatives, or other people for emotional, tangible, or informational support. As we discussed earlier in the chapter, having a strong network of social support can help buffer the impact of stressors (Uchino, 2009). Confiding in a trusted friend gives you an opportunity to vent your emotions and better understand the stressful situation.

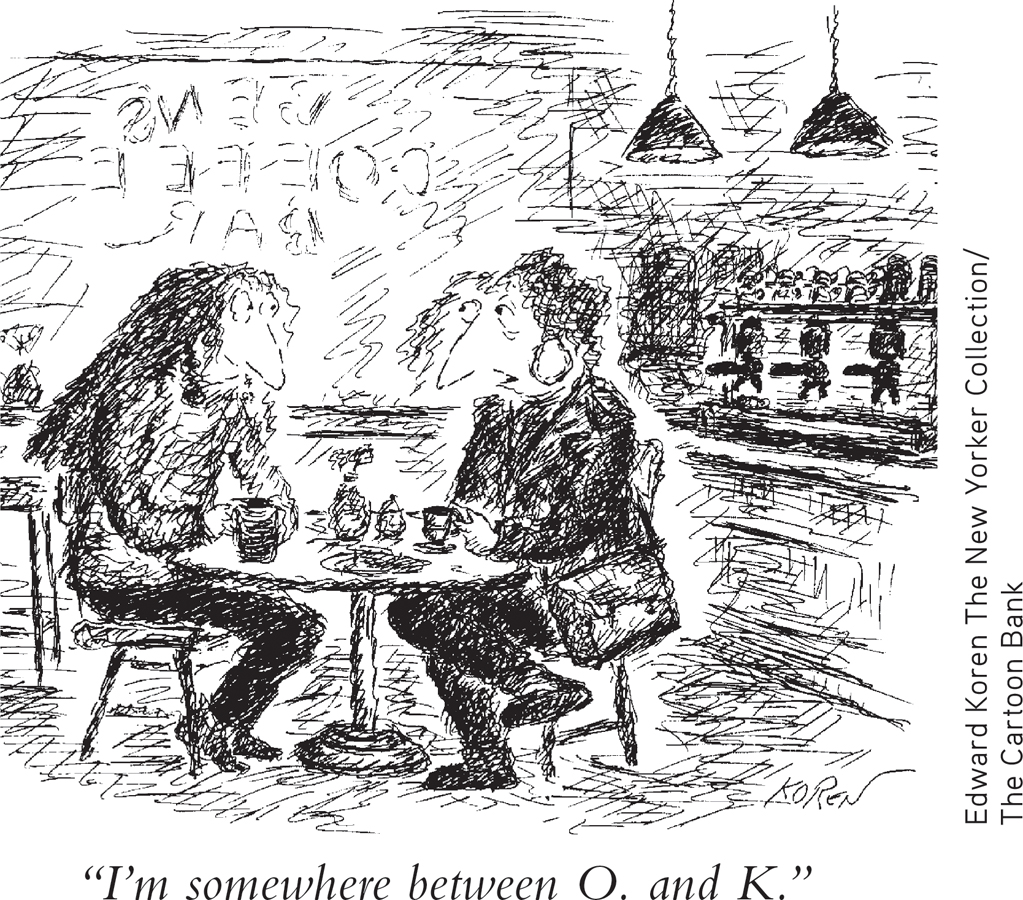

When you acknowledge the stressor but attempt to minimize or eliminate its emotional impact, you’re engaging in the coping strategy called distancing. Having an attitude of joy and lightheartedness in daily life, and finding the humor in life’s absurdities or ironies, is one form of distancing (Kuhn & others, 2010; McGraw & others, 2013). Sometimes people emotionally distance themselves from a stressor by discussing it in a detached, depersonalized, or intellectual way.

Nemcova founded Happy Hearts Fund, an international foundation that has raised tens of millions of dollars and founded schools and clinics in areas hit by natural disasters around the world, including Thailand, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Nemcova is shown here at the opening of a kindergarten in an Indonesian village that was devastated by a powerful earthquake.

For example, when Andi planned her first trip up to her burned-out house to see what could be salvaged, she joked that we would be like pirates looking for booty in the wreckage. The admittedly silly joke caught on. Along with the pile of donated shovels, rakes, screens, face masks and heavy work gloves, one friend brought a handmade pirate flag and another a stuffed parrot! When we got to Andi’s home-site, she planted the flag on top of the only item of furniture that was still standing—her charred exercise bicycle.

In certain high-stress occupations, distancing can help workers cope with painful human problems. Clinical psychologists, social workers, rescue workers, police officers, and medical personnel often use distancing to some degree to help them deal with distressing situations without falling apart emotionally themselves.

In contrast to distancing, denial is a refusal to acknowledge that the problem even exists. Like escape–

Perhaps the most constructive emotion-focused coping strategy is positive reappraisal. When we use positive reappraisal, we try not only to minimize the negative emotional aspects of the situation but also to create positive meaning by focusing on personal growth (Folkman, 2009). Even in the midst of deeply disturbing situations, positive reappraisal can help people experience positive emotions and minimize the potential for negative aftereffects (Weiss & Berger, 2010).

For example, as Andi said, “Your life is terrible and wonderful at the same time. It’s terrible because you’ve lost everything you own. But it’s wonderful because you see the incredible kindness of strangers.”

Some people turn to their religious or spiritual beliefs to help them cope with stress. Positive religious coping includes seeking comfort or reassurance in prayer or from a religious community, or believing that your personal experience is spiritually meaningful. Positive religious coping is generally associated with lower levels of stress and anxiety, improved mental and physical health, and enhanced well-being (Ano & Vasconcelles, 2005).

On the other hand, religious beliefs can also lead to a less positive outcome. Individuals who respond with negative religious coping, in which they become angry, question their religious beliefs, or believe that they are being punished, tend to experience increased levels of distress, poorer health, and decreased well-being (Ano & Vasconcelles, 2005; Smith & others, 2005).

For many people, religious coping offers a sense of control or certainty during stressful events or circumstances (Hogg & others, 2010; Kay & others, 2010). For example, some people find strength in the notion that adversity is a test of their religious faith or that they have been given a particular challenge in order to fulfill a higher moral purpose. Religious beliefs and practices help some people feel more optimistic or hopeful during stressful times. For some people, religious or spiritual beliefs can increase resilience, optimism, and personal growth during times of stress and adversity (Pargament & Cummings, 2010).

IN FOCUS

Gender Differences in Responding to Stress: “Tend-and-Befriend” or “Fight-or-Flight”?

Physiologically, men and women show the same hormonal and sympathetic nervous system activation that Walter Cannon (1932) described as the “fight-or-flight” response to stress. Yet behaviorally, the two sexes react very differently.

To illustrate, consider this finding: When men come home after a stressful day at work, they tend to withdraw from their families, wanting to be left alone—an example of the “flight” response (Repetti & others, 2009). After a stressful workday, however, women tend to seek out interactions with their marital partners (Schulz & others, 2004). And, women tend to be more nurturing toward their children, rather than less (Campos & others, 2009).

As we have noted in this chapter, women tend to be much more involved in their social networks than men. And, as compared to men, women are much more likely to seek out and use social support when they are under stress. Throughout their lives, women tend to mobilize social support—especially from other women—in times of stress (Zwicker & DeLongis, 2010).

Why the gender difference in coping with stress? Health psychologists Shelley Taylor and her colleagues (Taylor, 2000; Taylor & Gonzaga, 2007) believe that evolutionary theory offers some insight. According to the evolutionary perspective, the most adaptive response in virtually any situation is one that promotes the survival of both the individual and the individual’s offspring (Taylor & Master, 2011). Given that premise, neither fighting nor fleeing is likely to have been an adaptive response for females, especially females who were pregnant, nursing, or caring for their offspring. According to Taylor (2006), “Tending to offspring in times of stress would be vital to ensuring the survival of the species.” Rather than fighting or fleeing, they argue, women developed a tend-and-befriend behavioral response to stress.

What is the “tend-and-befriend” pattern of responding? Tending refers to “quieting and caring for offspring and blending into the environment,” Taylor and her colleagues (2000) write. That is, rather than confronting or running from the threat, females take cover and protect their young. Evidence supporting this behavior pattern includes studies showing that many female animals adopt a “tending” strategy when faced by a threat (Taylor, 2006; Trainor & others, 2010).

The “befriending” side of the equation relates to women’s tendency to seek social support during stressful situations. Befriending is the creation and maintenance of social networks that provide resources and protection for the female and her offspring under conditions of stress (Taylor & Master, 2011).

However, both males and females show the same neuroendocrine responses to an acute stressor—the sympathetic nervous system activates, stress hormones pour into the bloodstream, and, as those hormones reach different organs, the body kicks into high gear. So why do women “tend and befriend” rather than “fight or flee,” as men do? Taylor points to the effects of another hormone, oxytocin. Higher in females than in males, oxytocin is associated with maternal behaviors in all female mammals, including humans. Oxytocin also tends to have a calming effect on both males and females (see Southwick & others, 2005).

Taylor speculates that oxytocin might simultaneously help calm stressed females and promote affiliative behavior. Supporting this speculation is research showing that oxytocin increases affiliative behaviors and reduces stress in many mammals (Taylor & Master, 2011). For example, one study found that healthy men who received a dose of oxytocin before being subjected to a stressful procedure were less anxious and had lower cortisol levels than men who received a placebo (Heinrichs & others, 2003).

In humans, oxytocin is highest in nursing mothers. Pleasant physical contact, such as hugging, cuddling, and touching, stimulates the release of oxytocin. In combination, all of these oxytocin-related changes seem to help turn down the physiological intensity of the fight-or-flight response for women. And perhaps, Taylor suggests, they also promote the tend-and-befriend response.

Think Like a SCIENTIST

Can you reduce your stress level by watching cute animal videos? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about Coping with Stress.

Finally, it’s important to note that there is no single “best” coping strategy. In general, the most effective coping is flexible, meaning that we fine-tune our coping strategies to meet the demands of a particular stressor (Carver, 2011; Cheng, 2009). And, people often use multiple coping strategies, combining problem-focused and emotion-focused forms of coping. In the initial stages of a stressful experience, we may rely on emotion-focused strategies to help us step back emotionally from a problem. Once we’ve regained our equilibrium, we may use problem-focused coping strategies to identify potential solutions.

Although it’s virtually inevitable that you’ll encounter stressful circumstances, there are coping strategies that can help you minimize their health effects. We suggest several techniques in the Psych for Your Life section at the end of the chapter.

Question 13.12

f4AdxClOlstaGG8FZmRqYLNFhXqFe6ajlZ5qSkowZccTcqNt3/LlTdOxVyv+gAFDIaAguOrwURwRpLjWGAqvs2fm9KNt5C5y5FAudmfr7w2i4CbVfoEaXGkQR+Zj23LDG7ojwmY2iFhR8h+OJ4snBPvbc26Q6ZffKtx+eyzr5/Ql8G4zHzjZCe/NNw3ve75MnSIeKgdBYMw5w6vqtkGM3LwgZsFyS3Tvk/UZIw4cgQBVWoY5DXmNpY8DYaLEgrLqi14iAYNxYxd2wsnvCulture and Coping Strategies

Culture can influence the choice of coping strategies (Chun & others, 2006). Americans and other members of individualistic cultures tend to emphasize personal autonomy and personal responsibility in dealing with problems. Thus, they are less likely to seek social support in stressful situations than are members of collectivistic cultures, such as Asian cultures (Wong & Wong, 2006). Members of collectivistic cultures tend to be more oriented toward their social group, family, or community and toward seeking help with their problems.

Individualists also tend to emphasize the importance and value of exerting control over their circumstances, especially circumstances that are threatening or stressful (O’Connor & Shimizu, 2002). Thus, they favor problem-focused strategies, such as confrontive coping and planful problem solving. These strategies involve directly changing the situation to achieve a better fit with their wishes or goals (Wong & Wong, 2006).

In collectivistic cultures, however, a greater emphasis is placed on controlling your personal reactions to a stressful situation rather than trying to control the situation itself (Zhou & others, 2012). According to some researchers, people in China, Japan, and other Asian cultures are more likely to rely on emotional coping strategies than people in individualistic cultures. Coping strategies that are particularly valued in collectivistic cultures include emotional self-control, gracefully accepting one’s fate and making the best of a bad situation, and maintaining harmonious relationships with family members (Heppner, 2008; Yeh & others, 2006). This emotion-focused coping style emphasizes gaining control over inner feelings by accepting and accommodating yourself to existing realities (O’Connor & Shimizu, 2002).

For example, the Japanese emphasize accepting difficult situations with maturity, serenity, and flexibility (Gross, 2007). Common sayings in Japan are “The true tolerance is to tolerate the intolerable” and “Flexibility can control rigidity.” Along with controlling inner feelings, many Asian cultures also stress the goal of controlling the outward expression of emotions, however distressing the situation (Park, 2010).

These cultural differences in coping underscore the point that there is no formula for effective coping in all situations. That we use multiple coping strategies throughout almost every stressful situation reflects our efforts to identify what will work best at a given moment in time. To the extent that any coping strategy helps us identify realistic alternatives, manage our emotions, and maintain important relationships, it is adaptive and effective.

CONCEPT REVIEW 13.3

Psychological Factors and Stress Coping Strategies

Identify the coping strategy that is being illustrated in each of the scenarios below.

seeking social support

positive reappraisal

distancing

escape–avoidance

confrontive coping

planful problem solving

denial

Question 13.13

| 1. | ____ Although she failed her midterm exam and got a D on her term paper, Olivia insists that she is going to get a B in her economics course. |

Question 13.14

| 2. | ____ After spending several days in the hospital with a family member who was seriously injured in a motorcycle accident, Chris did very poorly on his last two tests and was very concerned about his GPA. Chris decided to talk with his professor about the possibility of writing an extra paper or taking a makeup exam. |

Question 13.15

| 3. | ____ Faced with low productivity and mounting financial losses, the factory manager bluntly told all his workers, “You people had better start getting more work done in less time, or you will be looking for jobs elsewhere.” |

Question 13.16

| 4. | ____ Jake’s job as a public defender is filled with long days and little thanks. To take his mind off his job, Jake jogs every day. |

Question 13.17

| 5. | ____ Whenever Dr. Mathau has a particularly hectic and stressful shift in the emergency room, she finds herself making jokes and facetious remarks to the other staff members. |

Question 13.18

| 6. | ____ Lionel was disappointed that he did not get the job, but he concluded that the knowledge he gained from the application and interview process was very beneficial. |

Question 13.19

| 7. | ____ In trying to contend with her stormy marriage, Emily often seeks the advice of her best friend, Caitlin. |

Test your understanding of Coping: How People Deal with Stress with

.

.

Closing Thoughts

From disasters and major life events to the minor hassles and annoyances of daily life, stressors come in all sizes and shapes. Stress is an unavoidable part of life. If prolonged or intense, stress can adversely affect both our physical and psychological well-being. Fortunately, most of the time people deal effectively with the stresses in their lives. But effective coping can minimize the effects of even the most intense stressors, like losing your home in a fire.

Ultimately, the level of stress that we experience is due to a complex interaction of psychological, biological, and social factors. We hope that reading this chapter has given you a better understanding of how stress affects your life and how you can reduce its impact on your physical and psychological well-being. In Psych for Your Life, we’ll suggest some concrete steps you can take to minimize the harmful impact of stress in your life.