15.3 Humanistic Therapy

KEY THEME

The most influential humanistic psychotherapy is client-centered therapy, which was developed by Carl Rogers.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the key assumptions of humanistic therapy, including client-centered therapy?

What therapeutic techniques and conditions are important in client-centered therapy?

How do client-centered therapy and psychoanalysis differ?

The humanistic perspective in psychology emphasizes human potential, self-awareness, and freedom of choice (see Chapter 11). Humanistic psychologists contend that the most important factor in personality is the individual’s conscious, subjective perception of his or her self. They see people as being innately good and motivated by the need to grow psychologically. If people are raised in a genuinely accepting atmosphere and given freedom to make choices, they will develop healthy self-concepts and strive to fulfill their unique potential as human beings (Kirschenbaum & Jourdan, 2005; Pos & others, 2008).

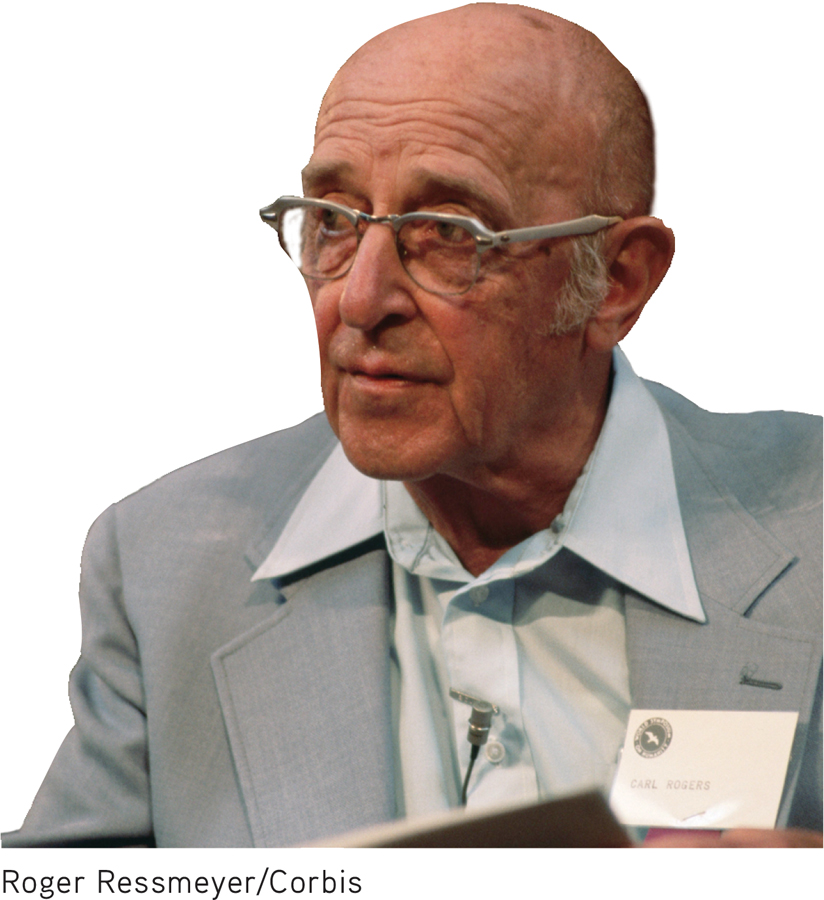

Carl Rogers and Client-Centered Therapy

The humanistic perspective has exerted a strong influence on psychotherapy (Cain, 2002, 2003; Schneider & Krug, 2009). Probably the most influential of the humanistic psychotherapies is client-centered therapy, also called person-centered therapy, developed by Carl Rogers. In naming his therapy, Rogers (1951) deliberately used the word client rather than patient. He believed that the medical term patient implied that people in therapy were “sick” and were seeking treatment from an all-knowing authority figure who could “heal” or “cure” them. Instead of stressing the therapist’s expertise or perceptions of the patient, client-centered therapy emphasizes the client’s subjective perception of himself and his environment (Cain, 2002; Raskin & Rogers, 2005).

client-centered therapy

A type of psychotherapy developed by humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers in which the therapist is nondirective and reflective, and the client directs the focus of each therapy session; also called person-centered therapy.

Like Freud, Rogers saw the therapeutic relationship as the catalyst that leads to insight and lasting personality change. But Rogers viewed the nature of this relationship very differently from Freud. According to Rogers (1977), the therapist should not exert power by offering carefully timed “interpretations” of the patient’s unconscious conflicts. Advocating just the opposite, Rogers believed that the therapist should be nondirective. That is, the therapist must not direct the client, make decisions for the client, offer solutions, or pass judgment on the client’s thoughts or feelings. Instead, Rogers believed, change in therapy must be chosen and directed by the client (Bozarth & others, 2002). The therapist’s role is to create the conditions that allow the client, not the therapist, to direct the focus of therapy.

An empathic way of being with another person has several facets. It means entering the private perceptual world of the other and becoming thoroughly at home in it. It involves being sensitive, moment by moment, to the changing felt meanings which flow in this other person, to the fear or rage or tenderness or confusion or whatever that he or she is experiencing.

—Carl Rogers (1980)

What are the therapeutic conditions that promote self-awareness, psychological growth, and self-directed change? Rogers (1957c, 1980) believed that three qualities of the therapist are necessary: genuineness, unconditional positive regard, and empathic understanding. First, genuineness means that the therapist honestly and openly shares her thoughts and feelings with the client. By modeling genuineness, the therapist indirectly encourages the client to exercise this capability more fully in himself.

Second, the therapist must value, accept, and care for the client, whatever her problems or behavior. Rogers called this quality unconditional positive regard (Bozarth & Wang, 2008). Rogers believed that people develop psychological problems largely because they have consistently experienced only conditional acceptance. That is, parents, teachers, and others have communicated this message to the client: “I will accept you only if you conform to my expectations.” Because acceptance by significant others has been conditional, the person has cut off or denied unacceptable aspects of herself, distorting her self-concept. In turn, these distorted perceptions affect her thoughts and behaviors in unhealthy, unproductive ways. The therapist who successfully creates a climate of unconditional positive regard fosters the person’s natural tendency to move toward self-fulfilling decisions without fear of evaluation or rejection.

Third, the therapist must communicate empathic understanding by reflecting the content and personal meaning of the feelings being experienced by the client. In effect, the therapist creates a psychological mirror, reflecting the client’s thoughts and feelings as they exist in the client’s private inner world. The goal is to help the client explore and clarify his feelings, thoughts, and perceptions. In the process, the client begins to see himself, and his problems, more clearly (Freire, 2007).

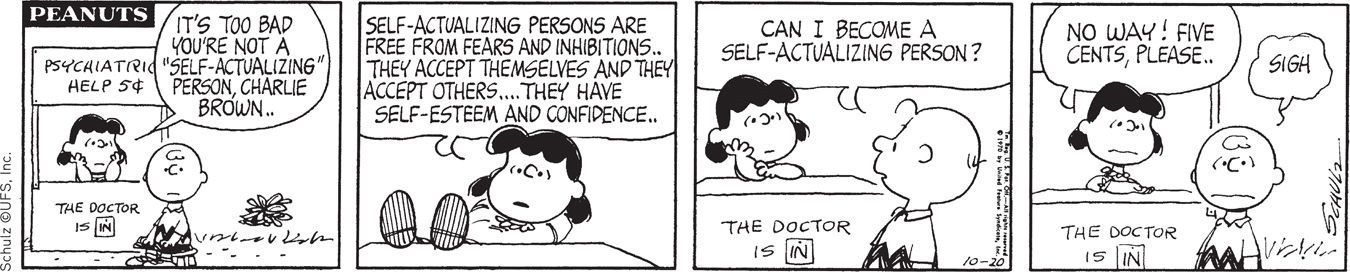

Empathic understanding requires the therapist to listen actively for the personal meaning beneath the surface of what the client is saying (Watson, 2002). Rogers believed that when the therapeutic atmosphere contains genuineness, unconditional positive regard, and empathic understanding, change is more likely to occur. Such conditions foster feelings of being psychologically safe, accepted, and valued. In this therapeutic atmosphere, change occurs as the person’s self-concept and worldview gradually become healthier and less distorted. In effect, the client is moving in the direction of self-actualization—the realization of his or her unique potentials and talents.

A large number of studies have generally supported the importance of genuineness, unconditional positive regard, and empathic understanding (Elliott & others, 2004; Greene, 2008). Such factors promote trust and self-exploration in therapy. However, these conditions, by themselves, may not be sufficient to help clients change (Cain & Seeman, 2002; Sachse & Elliott, 2002).

Question 15.3

yr1mjfcXDS0YEY6HfSLOcS8txxii0NfSXLRA4yU/wkto13PUc92xbWq1PnyxcTt01idzuS8VkvS7HFX/z93bliaaVN08tTkt1NyxG1eoKSi4owTx7j/2QYvBLJiDuSikEQRgR9W61nTQ4BEThmiPT4f7d4LJ7KIq8D9BFSdU+VHhsGo2gECqgUQyC1vGUiuylQABhNw5hz+SHEMVyyJJCRFo0j5tU2S79djoz/JcyfAVRYmKNv/LuQZFSk2nCutan8GV0Ln31ayjruJVY+8u2ypDQX8hbv+JHwRfkUIKrROQ8IR8MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING: HELPING CLIENTS COMMIT TO CHANGE

Like psychoanalysis, client-centered therapy has evolved and adapted to changing times. It continues to have a powerful impact on therapists, teachers, social workers, and counselors (see Cooper & others, 2013). Of particular note has been the development of motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). Motivational interviewing (MI) is designed to help clients overcome the mixed feelings or reluctance they might have about committing to change. MI is used for a range of psychological problems, but has most frequently been applied to addictions, such as substance use disorders or gambling, or to techniques to improve health, such as through diet or exercise (Lundahl & others, 2010). Usually lasting only a session or two, MI is more directive than traditional client-centered therapy (Arkowitz & others, 2007; Hettema & others, 2005).

The main goal of MI is to encourage and strengthen the client’s self-motivating statements, or “change talk” (Hayes & others, 2011). These are expressions of the client’s need, desire, and reasons for change. Using client-centered techniques, the therapist responds with empathic understanding and reflective listening, helping the client explore his or her own values and motivations for change. When the client expresses reluctance, the therapist acknowledges the mixed feelings and redirects the emphasis toward change (Miller & Rose, 2009). As Jennifer Hettema and her colleagues (2005) explain:

The counselor seeks to evoke the client’s own motivation, with confidence in the human desire and capacity to grow in positive directions. Instead of implying that “I have what you need,” MI communicates, “You have what you need.” In this way, MI falls squarely within the humanistic “third force” in the history of psychotherapy.

Along with being influential in individual psychotherapy, the client-centered approach has been applied to group therapy, marital counseling, parenting, education, business, and even community and international relations (Chen & others, 2011; Henderson & others, 2007; Wagner & Ingersoll, 2012). TABLE 15.2 compares some aspects of psychoanalysis and client-centered therapy.

Comparing Psychodynamic and Humanistic Therapies

| Type of Therapy | Founder | Source of Problems | Treatment Techniques | Goals of Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychoanalysis | Sigmund Freud | Repressed, unconscious conflicts stemming from early childhood experiences | Free association, analysis of dream content, interpretation, and transference | To recognize, work through, and resolve long-standing conflicts |

| Client-centered therapy | Carl Rogers | Conditional acceptance that causes the person to develop a distorted self-concept and worldview | Nondirective therapist who displays unconditional positive regard, genuineness, and empathic understanding | To develop self-awareness, self-acceptance, and self-determination |

Test your understanding of Psychotherapy and Humanistic Therapy with

.

.