1.7 PSYCH FOR YOUR LIFE

Successful Study Techniques

Psychologists have conducted literally thousands of research studies investigating learning and memory. In Chapter 6, you’ll learn some strategies to improve your memory for specific tasks, such as memorizing lists of items. For now, here are six research-based suggestions that you can use to help you study more effectively—and succeed in this course and others.

1. Focus your attention

Many students think they are good multi-taskers. But do you remember the correlational research on multi-tasking during studying? The psychological research is clear: Attention is a limited resource (Chun & others, 2011). So, when you sit down to study, put your cell phone on “silent” and try to avoid going online except for topic-related material. If you find it hard to stay on task, set a timer on your phone and challenge yourself to read for 30 minutes without interruption. You’ll be amazed at how much more efficient your studying is.

2. Engage your mind: Be an active reader

One of the most common study techniques used by students is to highlight or underline text in handouts and textbooks. Highlighting and underlining can be helpful, but only if done properly (Dunlosky & others, 2013).

Research has found that you’re more likely to remember text marked by highlighting or underlining. The problem is that you are less likely to remember material that you don’t mark. Thus, if you highlight the wrong material, highlighting may be more harmful than helpful. It’s also a problem if you highlight too much material. If your textbook looks like your younger brother’s coloring book, you’re probably doing it wrong. One early study found a negative correlation (see p. 25 if you don’t remember what that means) between the amount of text highlighted and test scores over the material: The more material students highlighted, the lower their test scores (Fowler & Barker, 1974).

How can you use highlighting and underlining to improve learning? Be an active reader—and a selective highlighter, highlighting only the most important information. If you have a tendency to highlight entire paragraphs, instead choose no more than one or two points per paragraph to highlight. In this textbook, the “Key Questions” at the beginning of each section will help you identify the most important points.

3. In the classroom, take notes by hand, not on your laptop

A new study shows that using handwriting to take notes rather than typing notes on a laptop increases both conceptual understanding and factual retention of the material. Students also had higher test scores when they studied from their handwritten notes versus studying from typed notes, even though their typed notes included more information. The explanation? Students who typed on a laptop tended to simply transcribe verbatim what they heard. In contrast, note-takers using longhand had to listen, digest, and summarize the information in their own words. Doing so required them to deeply engage with the material, which led to better memory for the material (Mueller & Oppenheimer, 2014). Paying attention pays off!

4. Practice retrieval: The testing effect

Hundreds of experiments have shown that tests do more than simply assess learning; they are powerful tools in their own right (see Dunlosky & others, 2013; Bjork & others, 2013). Earlier in the chapter, we described an experiment that demonstrated the power of the testing effect—the finding that retrieving information from memory produces better retention than restudying the same information (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006; Roediger & Butler, 2011).

Are practice tests helpful only for factual material? Does the testing effect only enhance rote memorization? No. Practice tests need not be multiple-choice or short-answer tests. Essay questions or other tasks that require you to retrieve information from your memory also produce improved retention (Roediger, Putnam, & Smith, 2011; Roediger, Agarwal, & others, 2011).

And, studies have shown that practice tests enhance memory for all types of information. Some examples include spatial information, such as map-learning, and even the learning of new skills like CPR (Dunlosky & others, 2013; Kromann & others, 2009). Research also shows that material learned via retrieval practice transfers to novel situations, when the material is tested in other ways. Thus, it represents more than “teaching to the test” (Roediger, Finn, & Weinstein, 2012).

Why is practice testing such a powerful study technique? One reason may be that practice tests counteract the fluency effect. When you reread text or review your notes, the material seems familiar and easy to understand, so the tendency is to assume that you know the material. But often we mistake familiarity for knowledge. Practice testing allows you to identify the gaps that exist in your knowledge so that you can better allocate your study time (Roediger, Putnam, & Smith, 2011).

Practice tests also allow you to practice the very skills that you will need to succeed—retrieving information you’ve learned from memory (Roediger, Finn, & Weinstein, 2012). And, some research suggests that repeatedly retrieving information seems to help you organize that information in memory, making it easier to remember in the future.

How can you incorporate practice tests into your own studying? Take advantage of any practice quizzes that may be offered by your professor, in study guides, or in your textbook. Challenge yourself to write out the definitions for each of the boldfaced key terms in each section of your text. Even simpler, duplicate the procedure used in the experiment described on pages 26–

5. Use flashcards and practice tests correctly

Millions of school children have been taught how to use flashcards: Quiz yourself, and if you answer an item correctly, set the card aside. Keep quizzing yourself on the remaining cards until all cards have been set aside, at which point you can conclude that you have successfully mastered the information.

But is this an effective study technique? Should students skip material that they have learned in order to focus their effort on material that they have not learned? Let’s take a look at a clever experiment that tested this notion.

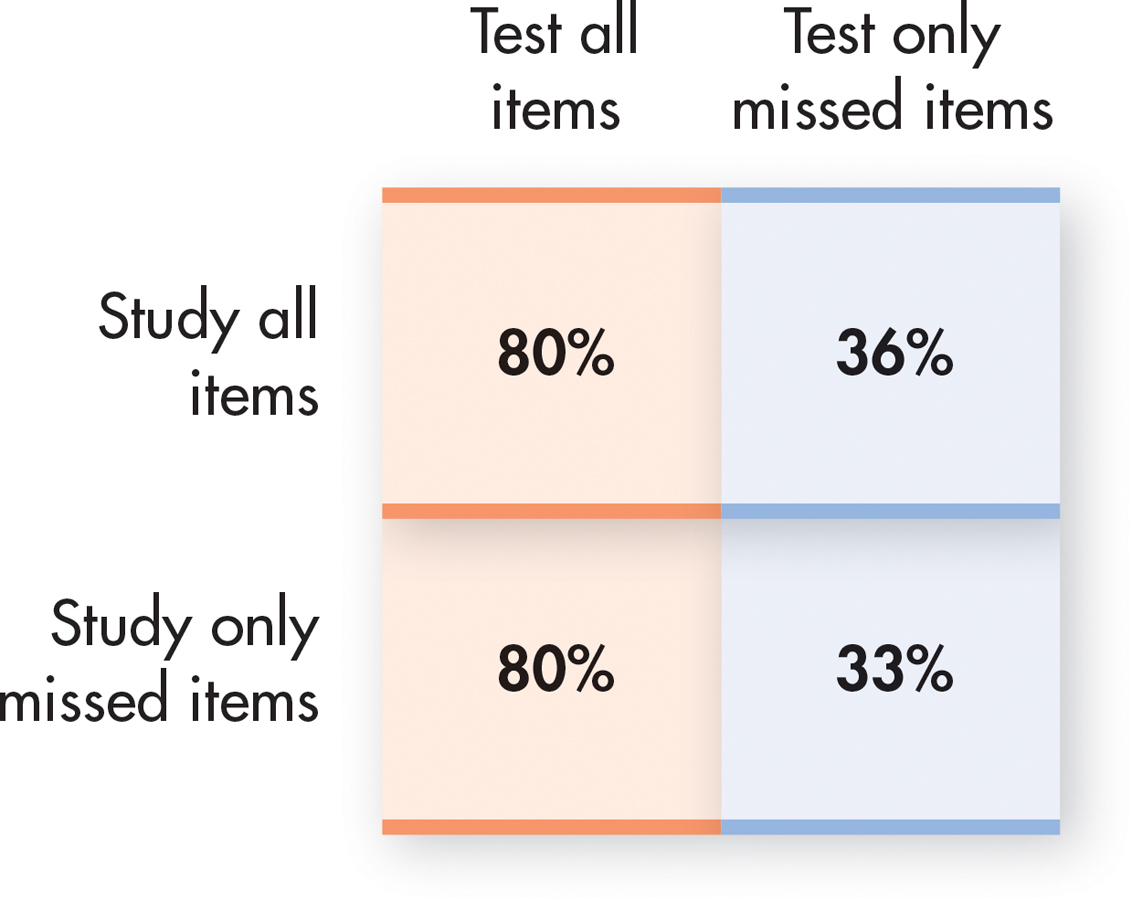

Jeffrey Karpicke & Henry Roediger (2008) gave participants a list of 40 Swahili words and their English translations. All of the participants studied and were tested on the complete list in first study session. Then, the participants were divided into four groups and tested a week later after completing three study/test sessions (see figure). The results:

Students who studied and were tested on the entire list in each study period scored 80% on the test a week later.

Participants who studied only the items they missed but were tested on the entire list also scored 80% on the test a week later.

Participants who studied all the items but were only tested on items they missed scored 36% on the test one week later.

Participants who, like the traditional flashcard user, only studied and were tested on items they missed scored 33% on the final test.

In other words, repeated study had no effect on final test performance—but repeated testing did. How can you apply this finding to your own study habits? For any type of practice test, don’t stop practicing items that you’ve answered correctly. Especially if you are using flashcards, don’t drop those cards once you think you have mastered the information—keep testing yourself on them.

Source: Data from Karpicke & Roediger (2008).

6. Space out your study time: The benefits of distributed vs. massed practice

Psychologists call it “massed practice.” Students call it “cramming.” A common strategy for time-challenged students, massed practice involves trying to study as much as possible in a short period of time, typically right before an exam. Interestingly, massed practice is effective—but only in the short term (Bjork & others, 2013). Typically, information learned through cramming is forgotten very quickly.

A much more effective study strategy is what psychologists call distributed practice, which means that you learn the information over several sessions, separated in time. Countless studies have shown that information learned over distributed sessions is much better retained than information learned in a single session (see Dunlosky & others, 2013; Roediger, Finn, & Weinstein, 2012). One reason may be that the time between sessions gives you a chance to organize and incorporate new information into your memory (Carpenter & others, 2012).

We hope you find these suggestions helpful, both in psychology and in your other courses. Welcome to psychology!