Chapter Introduction

MYTH OR SCIENCE?

Is it true …

That oxytocin is the “love hormone,” making people more trusting and empathic?

That even simple behaviors and abilities involve the activation of multiple parts of the brain?

That you only use 10% of your brain?

That because their brains are wired differently, men and women think, feel, and behave differently?

That the right brain is creative and intuitive, and the left brain is analytic and logical, but that left-brained people can educate their right brain?

That the brain is essentially “hard-wired” by adolescence?

2

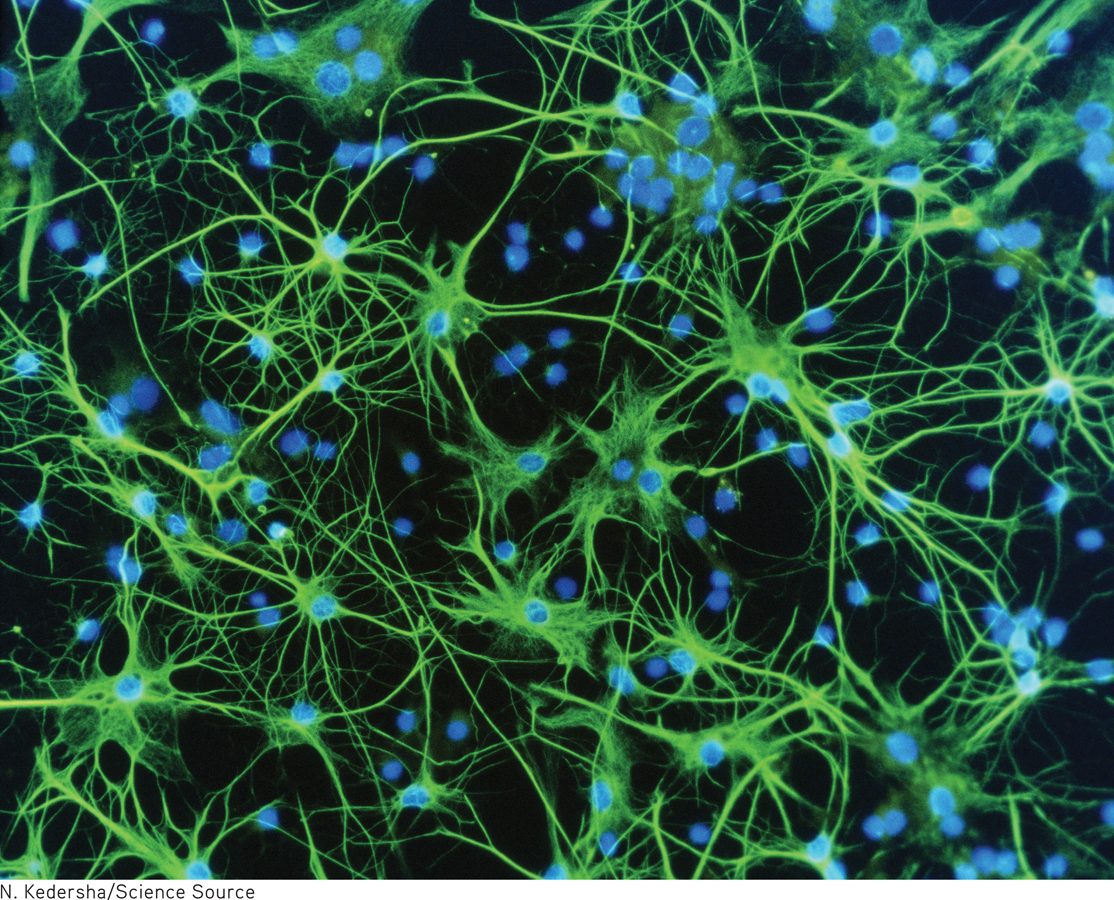

Neuroscience and Behavior

N. Kedersha/Science Source

Asha’s Story

PROLOGUE

IN THIS CHAPTER:

THE HEADACHES BEGAN WITHOUT WARNING. A pounding, intense pain just over Asha’s left temple. Asha just couldn’t seem to shake it—the pain was unrelenting. She was uncharacteristically tired, too.

But our friend Asha, a 32-year-old university professor, chalked up her constant headache and fatigue to stress and exhaustion. After all, the end of her demanding first semester of teaching and research was drawing near. Still, Asha had always been very healthy and usually tolerated stress well. She didn’t drink or smoke. And no matter how late she stayed up working on her lectures and research proposals, she still got up at 5:30 every morning to work out at the university gym.

There were other, more subtle signs that something was wrong. Asha’s husband, Paul, noticed that she had been behaving rather oddly in recent weeks. For example, at Thanksgiving dinner, Asha had picked up a knife by the wrong end and tried to cut her turkey with the handle instead of the blade. A few hours later, Asha had made the same mistake trying to use scissors: She held the blades and tried to cut with the handle.

Asha laughed these incidents off, and for that matter, so did Paul. They both thought she was simply under too much stress. And when Asha occasionally got her words mixed up, neither Paul nor anyone else was terribly surprised. Asha was born in India, and her first language was Tulu. Although Asha was extremely fluent in English, she often got English phrases slightly wrong—like the time she said that Paul was a “straight dart” instead of a “straight arrow.” Or when she said that it was “storming cats and birds” instead of “raining cats and dogs.”

There were other odd lapses in language. “I would say something, thinking it was correct,” Asha recalled, “and people would say to me, ‘What are you saying?’ I wouldn’t realize I was saying something wrong. I would open my mouth and just nonsense would come out. But it made perfect sense to me. At other times, the word was on the tip of my tongue—I knew I knew the word, but I couldn’t find it. I would fumble for the word, but it would come out wrong. Sometimes I would slur words, like I’d try to say ‘Saturday,’ only it would come out ‘salad day’.”

On Christmas morning, Paul and Asha were with Paul’s family, opening presents. Asha walked over to Paul’s father to look at the pool cue he had received as a gift. As she bent down, she fell forward onto her father-in-law. At first, everyone thought Asha was just joking around. But then she fell to the floor, her body stiff. Seconds later, it was apparent that Asha had lost consciousness and was having a seizure.

Asha remembers nothing of the seizure or of being taken by ambulance to the hospital intensive care unit. She floated in and out of consciousness for the first day and night. A CAT scan showed some sort of blockage in Asha’s brain. An MRI scan revealed a large white spot on the left side of her brain. At only 32 years of age, Asha had suffered a stroke—brain damage caused by a disruption of the blood flow to the brain.

She remained in the hospital for 12 days. It was only after Asha was transferred out of intensive care that both she and Paul began to realize just how serious the repercussions of the stroke were. Asha couldn’t read or write and had difficulty comprehending what was being said. Although she could speak, she could not name even simple objects, such as a tree, a clock, or her doctor’s tie. In this chapter, you will discover why the damage to Asha’s brain impaired her ability to perform simple behaviors, like naming common objects.