4.4 Dreams and Mental Activity During Sleep

KEY THEME

A dream is an unfolding sequence of perceptions, thoughts, and emotions that is experienced as a series of actual events during sleep.

KEY QUESTIONS

How does brain activity change during dreaming sleep, and how are those changes related to dream content?

What do people dream about, and why don’t we remember many of our dreams?

How do the psychoanalytic, activation-synthesis, and neurocognitive models explain the nature and function of dreams?

Dreams have fascinated people since the beginning of time. By adulthood, about 25 percent of a night’s sleep, or almost two hours every night, is spent dreaming. So, assuming you live to a ripe old age, you’ll devote more than 50,000 hours, or about six years of your life, to dreaming.

Although dreams may be the most interesting brain productions during sleep, they are not the most common. More prevalent is sleep thinking, also called sleep mentation. Sleep thinking usually occurs during NREM slow-wave sleep and consists of vague, bland, thoughtlike ruminations about real-life events (McCarley, 2007). Sometimes, sleep thinking interferes with sleep, such as when anxious students toss and turn, reviewing terms and concepts during the night before an important exam.

sleep thinking

Vague, bland, thoughtlike ruminations about real-life events that typically occur during NREM sleep; also called sleep mentation.

In contrast to sleep thinking, a dream is an unfolding sequence of perceptions, thoughts, and emotions during sleep that is experienced as a series of real-life events (Domhoff, 2005a, b). However bizarre the details or illogical the events, the dreamer accepts them as reality.

dream

An unfolding sequence of thoughts, perceptions, and emotions that typically occurs during REM sleep and is experienced as a series of real-life events.

Most dreams happen during REM sleep, although dreams also occur during NREM (Domhoff, 2011). When awakened during active REM sleep, people report a dream about 90 percent of the time, even people who claim that they never dream. The dreamer is usually the main participant in these events, and at least one other person is involved in the dream story. But sometimes the dreamer is simply the observer of the unfolding dream story.

People usually have four or five dreaming episodes each night. The first REM episode of the night is the shortest, lasting only about 10 minutes. Subsequent REM episodes average around 30 minutes and tend to get longer as the night continues. Early morning dreams, which can last 40 minutes or longer, are the dreams most likely to be recalled.

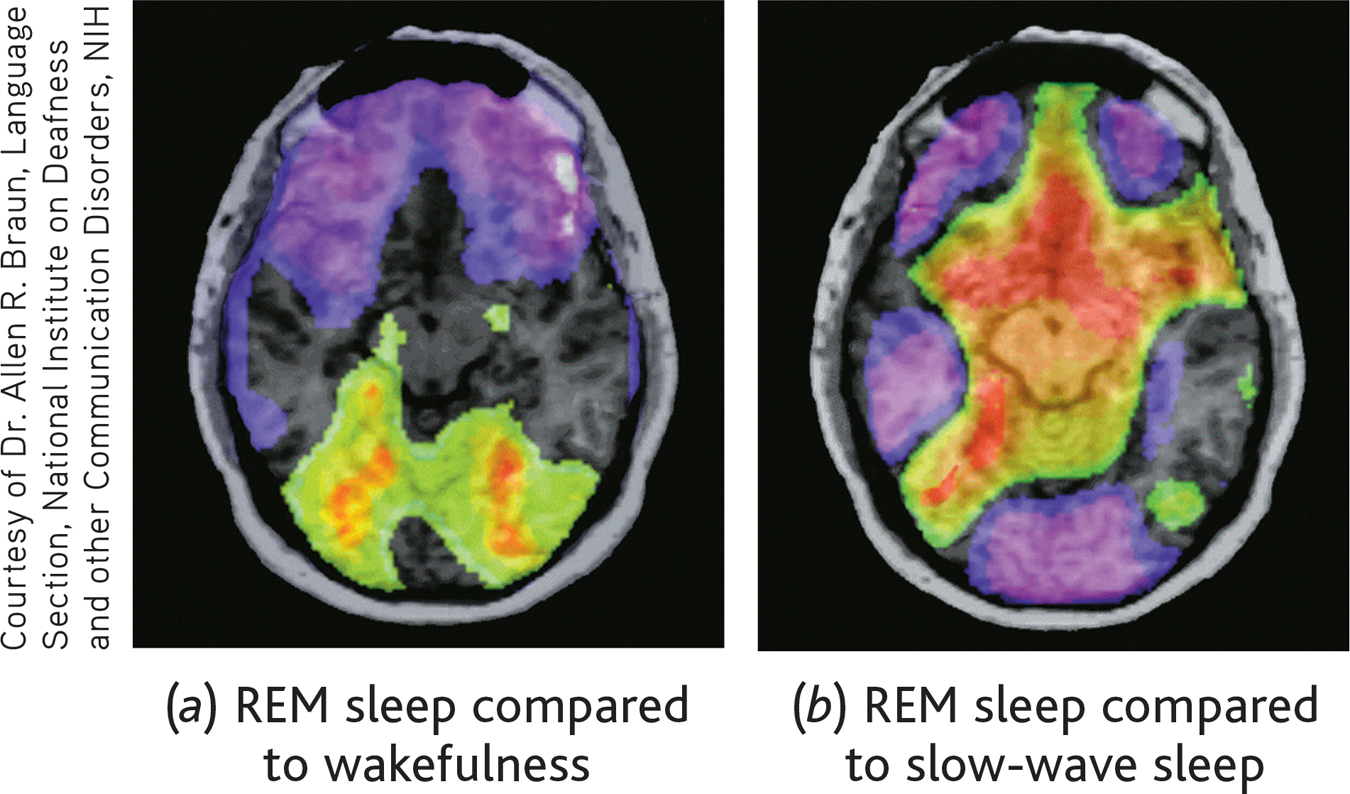

PET (positive-emission tomography) and fMRI scans have revealed that the brain’s activity during REM sleep is distinctly different from its activity during either wakefulness or NREM slow-wave sleep (Fuller & others, 2006; Nofzinger, 2006). These differences and the roles they play in dream content are explored in the Focus on Neuroscience box, “The Dreaming Brain.”

Dream Themes and Imagery

Although almost everyone can remember having had a bizarre dream, research on dream content shows that bizarre dream stories tend to be the exception, not the rule. As dream researcher William Domhoff (2007) points out, dreams tend be “far more coherent, patterned, and thoughtful than is suggested by the usual image of them.” Most dreams are about everyday settings, people, activities, and events. Common, however, are abrupt scene changes and unusual juxtapositions of images and actors.

In reviewing studies of dream content, Domhoff (2005b, 2010) has concluded that so-called common dream themes, like being naked in a public place, flying, or failing an exam, are actually quite rare in dream reports. And, dream emotions are usually appropriate in the context of the dream story (Domhoff, 2011). Based on studies of thousands of dream reports, Domhoff (2007, 2011) has identified the following common themes:

Women’s dreams involve an equal number of males and females, but men report more males as dream characters.

Negative feelings and events are more common than positive ones.

Aggressive actions are more common than friendly actions.

Dreamers are more likely to be victims of aggression than aggressors.

Men are much more likely than women to report instances of physical aggression.

Women are more likely than men to report experiencing emotions.

Sex or sexual behaviors are rare.

The most frequent emotions are apprehension and fear, followed by happiness and confusion.

FOCUS ON NEUROSCIENCE

The Dreaming Brain

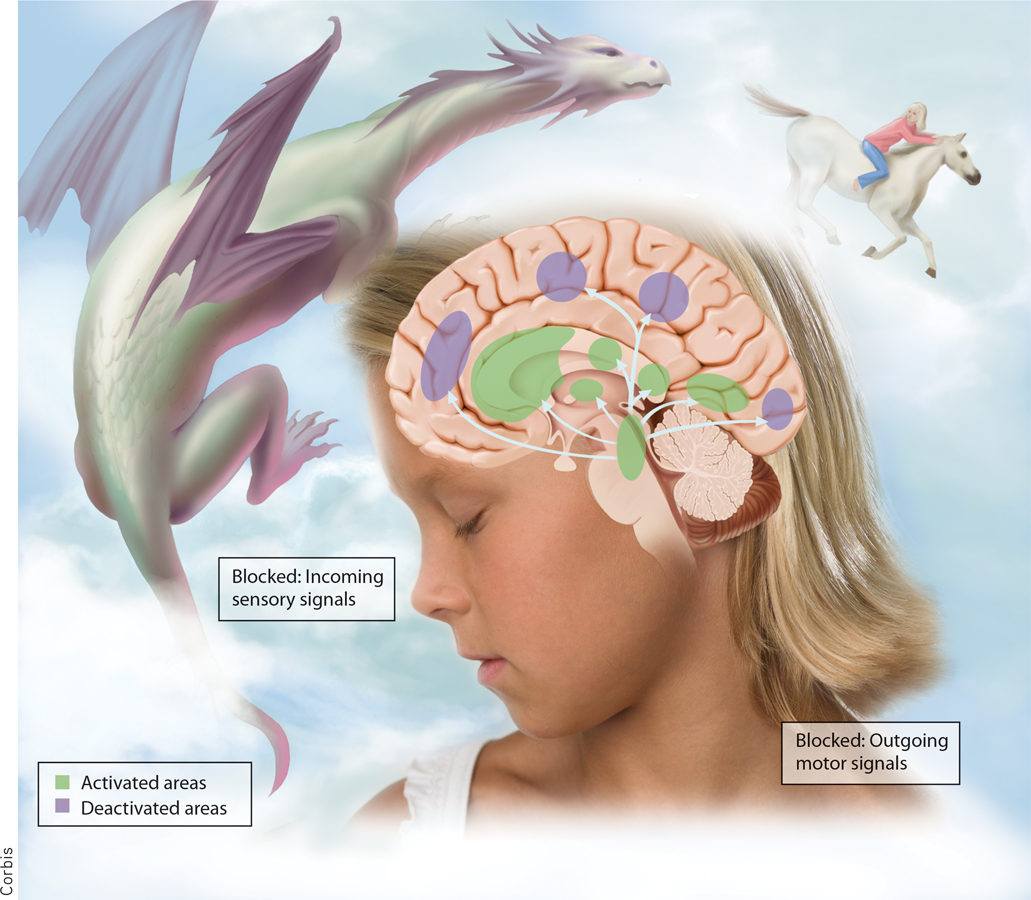

PET scan and other neuroimaging studies have revealed that the brain’s activity during REM sleep is distinctly different from its activity as compared to wakefulness (PET scan a) and NREM slow-wave sleep (PET scan b). To help orient you, the top of each PET scan corresponds to the front of the brain and the bottom to the back of the brain. The PET scans are color-coded: Bluish purple indicates areas of decreased brain activity and yellow-red indicates areas of increased brain activity.

Compared to wakefulness, PET scan a reveals that REM sleep involves decreased activity in the frontal lobes, which are involved in rational thinking. Also decreased is the activity of the primary visual cortex, which normally processes external visual stimuli. In effect, the dreamer is cut off from the reality-testing functions of the frontal lobes—a fact that no doubt contributes to the weirdness of some dreams. The yellow-red areas in PET scan a indicate increased activity in association areas of the visual cortex. This brain activation gives rise to the visual images occurring in a dream.

Compared to slow-wave sleep, the yellow-red areas in PET scan b indicate that REM sleep is characterized by a sharp increase in limbic system brain areas associated with emotion, motivation, and memory, including the amygdala and hippocampus. The activation of limbic system brain areas reflects the dream’s emotional qualities, which can sometimes be intense (Braun & others, 1998; Nofzinger, 2005).

If apprehensive or fearful emotions become progressively more intense as a dream story unfolds, the person may experience a nightmare. A nightmare is a vivid and disturbing dream that often awakens the sleeper. Typically, the dreamer feels helpless or powerless in the face of being aggressively attacked or pursued. Although fear, anxiety, and even terror are the most commonly experienced emotions, some nightmares involve intense feelings of sadness, anger, disgust, or embarrassment (Nielsen & Zadra, 2005).

nightmare

A vivid and frightening or unpleasant anxiety dream that occurs during REM sleep.

Nightmares are most common in childhood, but about 5 to 10 percent of adults report that they experience nightmares at least weekly. Women report more frequent nightmares than men. Daytime stress, anxiety, and emotional difficulties are often associated with nightmares. As a general rule, nightmares are not indicative of a psychological or sleep disorder unless they occur frequently, cause difficulties returning to sleep, or cause daytime distress (Levin & Nielsen, 2007; Nielsen & others, 2006).

Question 4.10

SFoPPB9CrpcGNpJS2elyHacsLXKv6QdtHqvb4yg1gtT50NOSKvscQuTpIU6nH+ycXxdSoLQYk+sjq926lfS7e3kcpcAHu/LKkcUfCw1+t0jBl5VWaDH8WIUdhSmYi3DTz/2WSUakMTj23wWLBAndT05UqR0CxBnBNp02qZ20H/Dxfrbah0ZUIUqouShAVsSVzGbsNw/BnkZXWABCioj1uDqPnPLFQRkps7rhrcMshmOFWO3HtAZyQoPwEZE=The Significance of Dreams

Why do we dream? Do dreams contain symbolic or hidden messages? In this section, we will look at three models of the nature and function of dreaming. We’ll start with the most famous one—the psychoanalytic explanation proposed by Sigmund Freud.

SIGMUND FREUD: DREAMS AS FULFILLED WISHES

In the chapters on personality and therapies (Chapters 11 and 15), we’ll look in detail at the ideas of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. As we discussed in Chapter 1, Freud believed that sexual and aggressive instincts are the motivating forces that dictate human behavior. Because these instinctual urges are so consciously unacceptable, sexual and aggressive thoughts, feelings, and wishes are pushed into the unconscious, or repressed. However, Freud believed that these repressed urges and wishes could surface in dream imagery.

In his landmark work, The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), Freud wrote that dreams are the “disguised fulfillments of repressed wishes” and provide “the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious mind.” In fact, he contended that “wish-fulfillment is the meaning of each and every dream.” According to the psychoanalytic view of dreaming, then, dreams function as a sort of psychological “safety valve” for the release of unconscious and unacceptable urges (see Yu, 2011).

Freud (1904) believed that dreams have two components: the manifest content, or the dream images themselves, and the latent content, the disguised psychological meaning of the dream. For example, Freud (1911) believed that dream images of sticks, swords, brooms, and other elongated objects were phallic symbols, representing the penis. Dream images of cupboards, boxes, and ovens supposedly symbolized the vagina.

manifest content

In Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, the elements of a dream that are consciously experienced and remembered by the dreamer.

latent content

In Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, the unconscious wishes, thoughts, and urges that are concealed in the manifest content of a dream.

In some types of psychotherapy today, especially those that follow Freud’s ideas, dreams are still seen as an important source of information about psychological conflicts (Auld & others, 2005; Pesant & Zadra, 2004). However, Freud’s belief that dreams represent the fulfillment of repressed wishes has not been substantiated by psychological research. Furthermore, research does not support Freud’s belief that the dream images themselves—the manifest content of dreams—are symbols that disguise the dream’s true psychological meaning (Domhoff, 2003, 2011).

THE ACTIVATION-SYNTHESIS MODEL OF DREAMING

Researchers J. Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley first proposed a new model of dreaming in 1977. Called the activation-synthesis model of dreaming, this model maintains that dreaming is our subjective awareness of the brain’s internally generated signals during sleep. Since it was first proposed, the model has evolved as new findings have been reported (see McCarley, 2007; Pace-Schott, 2005). Hobson’s most recent model, called the Activation-Input-Modulation (AIM) Model, is a more comprehensive attempt to relate dreaming to waking awareness with specific reference to the balance of neurotransmitters (Hobson, 2009).

activation-synthesis model of dreaming

The theory that brain activity during sleep produces dream images (activation), which are combined by the brain into a dream story (synthesis).

According to the activation-synthesis model, dreams occur when brainstem circuits at the base of the brain activate and trigger higher brain regions, including visual, motor, and auditory pathways (see FIGURE 4.6). As noted earlier in the Focus on Neuroscience box “The Dreaming Brain,” limbic system structures involved in emotion, such as the amygdala and hippocampus, are also activated during REM sleep. When we’re awake, these brain structures and pathways are involved in registering stimuli from the external world. But rather than responding to stimulation from the external environment, the dreaming brain is responding to its own internally generated signals (Hobson, 2005).

Other brain areas, highlighted in purple, are deactivated or blocked during dreaming. Outgoing motor signals and incoming sensory signals are blocked, keeping the dreamer from acting out the dream or responding to external stimuli (Pace-Schott, 2005). The logical, rational, and planning functions of the prefrontal cortex are suspended. Hence, dream stories can evolve in ways that seem disjointed or illogical. And because the prefrontal cortex is involved in processing memories, most nightly dream productions evaporate with no lingering memories of having had these experiences (Muzur & others, 2002).

Corbis

Both emotional salience and the cognitive mishmash of dreams are the undisguised read-out of the dreaming brain’s unique chemistry and physiology. This doesn’t mean that dreams make no psychological sense. On the contrary, dreams are dripping with emotional salience. Dreams can and should be discussed for their informative messages about the emotional concerns of the dreamer.

—J. Allan Hobson (1999)

In the absence of external sensory input, the activated brain combines, or synthesizes, these internally generated sensory signals and imposes meaning on them. The dream story itself is derived from a hodgepodge of memories, emotions, and sensations that are triggered by the brain’s activation and chemical changes during sleep. According to this model, then, dreaming is essentially the brain synthesizing and integrating memory fragments, emotions, and sensations that are internally triggered (Hobson & others, 1998, 2011).

The activation–

THE NEUROCOGNITIVE THEORY OF DREAMING

In contrast to the activation-synthesis model, the neurocognitive model of dreaming emphasizes the continuity between waking and dreaming cognition. According to William Domhoff (2005a, 2010, 2011), dreams are not a “cognitive mishmash” of random fragments of memories, images, and emotions generated by lower brainstem circuits, as the activation-synthesis model holds. Rather, dreams reflect our interests, personality, and individual worries (Nir & Tononi, 2010).

neurocognitive model of dreaming

Model of dreaming that emphasizes the continuity of waking and dreaming cognition, and states that dreaming is like thinking under conditions of reduced sensory input and the absence of voluntary control.

Further, the activation-synthesis model rests on the assumption that dreams result from brain activation during REM sleep. However, as Domhoff and other dream researchers point out, people also dream during NREM sleep, at sleep onset, and even experience dreamlike episodes while awake but drowsy (Nir & Tononi, 2010).

Like dreams, Domhoff (2011) notes, waking thought can also be marked by spontaneous mental images, rapid shifts of scene or topic, and unrealistic or fanciful thoughts. Thus, dreams are not as foreign to our waking experience as the activation-synthesis model claims. Instead, dreams mirror our waking concerns, and do so in a way that is remarkably similar to normal thought processes.

Test your understanding of Sleep and Dreams with

.

.

IN FOCUS

What You Really Want to Know About Dreams

If I fall off a cliff in my dreams and don’t wake up before I hit the bottom, will I die?

The first obvious problem with this bit of folklore is that if you did die before you woke up, how would anyone know what you’d been dreaming about? Beyond this basic contradiction, studies have shown that about a third of dreamers can recall a dream in which they died or were killed.

Do animals dream?

Virtually all mammals and birds experience sleep cycles in which REM sleep alternates with slow-wave NREM sleep. Animals clearly demonstrate perception and memory. They also communicate using vocalizations, facial expressions, posture, and gestures to show territoriality and sexual receptiveness. Thus, it’s quite reasonable to conclude that the brain and other physiological changes that occur during animal REM sleep are coupled with mental images.

What do blind people “see” when they dream?

People who become totally blind before the age of 5 typically do not have visual dreams as adults. Even so, their dreams are just as complex and vivid as sighted people’s dreams; they just involve other sensations—of sound, taste, smell, and touch.

Is it possible to control your dreams?

Yes, if you have lucid dreams. A lucid dream is one in which you become aware that you are dreaming while you are still asleep. About half of all people can recall at least one lucid dream, and some people frequently have lucid dreams. The dreamer can often consciously guide the course of a lucid dream, including backing it up and making it go in a different direction.

Can you predict the future with your dreams?

History is filled with stories of dream prophecies. Over the course of your life, you will have over 100,000 dreams. Simply by chance, it’s not surprising that every now and then a dream contains elements that coincide with future events.

Are dreams in color or black and white?

Up to 80 percent of our dreams contain color. When dreamers are awakened and asked to match dream colors to standard color charts, soft pastel colors are frequently chosen.

Sources: Empson (2002); Hobson & Voss (2010); Hurovitz & others (1999); Ross & others (2010); Voss & others (2009, 2014).