4.5 Sleep Disorders

KEY THEME

Sleep disorders are surprisingly common, take many different forms, and interfere with a person’s daytime functioning.

KEY QUESTIONS

What are the two broad categories of sleep disorders?

What are insomnia, sleep apnea, and narcolepsy?

What kinds of behavior are displayed in the different parasomnias?

Data from the National Sleep Foundation’s annual polls indicate that about 7 out of 10 people experience regular sleep disruptions. Such disruptions become a sleep disorder when (1) abnormal sleep patterns consistently occur, (2) they cause subjective distress, and (3) they interfere with a person’s daytime functioning (Thorpy, 2005; Thorpy & Plazzi, 2010).

sleep disorders

Serious and consistent sleep disturbances that interfere with daytime functioning and cause subjective distress.

Sleep disorders fall into two broad categories. Dyssomnias are sleep disorders involving disruptions in the amount, quality, or timing of sleep. Obstructive sleep apnea and narcolepsy are examples of dyssomnias. The parasomnias are sleep disorders involving undesirable physical arousal, behaviors, or events during sleep or sleep transitions.

dyssomnias

(dis-SOM-nee-uz) A category of sleep disorders involving disruptions in the amount, quality, or timing of sleep; includes insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea, and narcolepsy.

parasomnias

(pare-uh-SOM-nee-uz) A category of sleep disorders characterized by arousal or activation during sleep or sleep transitions; includes sleepwalking, sleep terrors, sleepsex, sleep-related eating disorder, and REM sleep behavior disorder.

Insomnia

Insomnia is not defined solely based on how long a person sleeps. Why? Put simply, because people vary in how much sleep they need to feel refreshed. Rather, insomnia is diagnosed when people repeatedly (1) are dissatisfied with the quality or duration of their sleep; (2) experience onset insomnia, meaning that they have difficulty falling asleep, or maintenance insomnia, meaning they have difficulty staying asleep; or (3) wake before it is time to get up. Regularly taking 30 minutes or longer to fall asleep is considered to be a symptom of insomnia. These disruptions must also produce daytime sleepiness, fatigue, impaired social or occupational performance, or mood disturbances (Bootzin & Epstein, 2011).

insomnia

A condition in which a person regularly experiences an inability to fall asleep, to stay asleep, or to feel adequately rested by sleep.

Insomnia is the most common sleep complaint among adults. Although many people occasionally have trouble falling asleep, about 10% of adults experience chronic insomnia for a month or longer (Mahowald & Schenck, 2005).

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

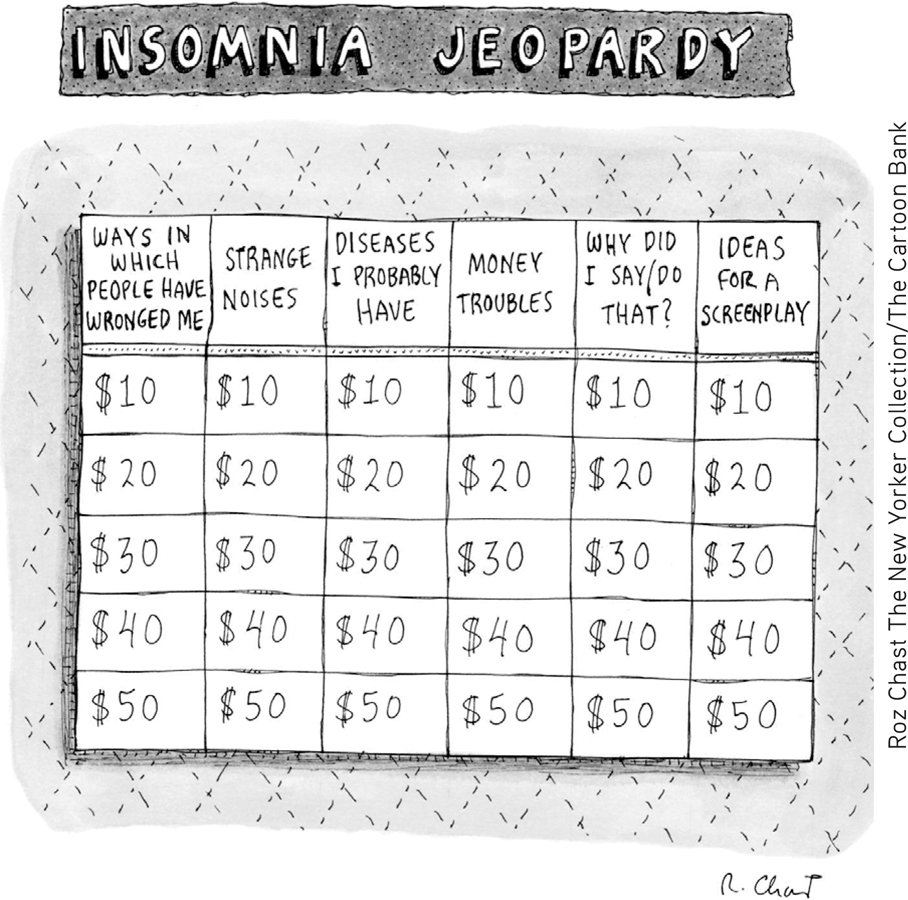

Is it true that sleeping pills are an effective way to treat chronic insomnia?

One common cause of insomnia is hyperarousal (Salas & others, 2014). Excitement about an upcoming event or the use of stimulants, like nicotine and caffeine, can make it hard to fall asleep. Most commonly, insomnia can be traced to anxiety over stressful life events, such as job, school, or relationship difficulties. Sometimes, worry about inadequate sleep can itself cause insomnia. Creating a vicious circle, concerns about the inability to sleep make disrupted sleep even more likely, further intensifying anxiety and worry over personal difficulties, producing more sleep difficulties, and so on (Perlis & others, 2005). Although the occasional use of prescription “sleeping pills” can be helpful to treat transient insomnia, frequent use, or use for chronic insomnia, is problematic. Along with having harmful side effects, they do not offer a long-term solution to the problem, since the insomnia returns if the pills are not used. In Psych for Your Life, we’ll describe one effective behavioral treatment for insomnia and give you several suggestions to improve the quality of your sleep.

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

BLOCKED BREATHING DURING SLEEP

Excessive daytime sleepiness is a key symptom of the second most common sleep disorder. In obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the sleeper’s airway becomes narrowed or blocked, causing very shallow breathing or repeated pauses in breathing. Each time breathing stops, oxygen blood levels decrease and carbon dioxide blood levels increase, triggering a momentary awakening. Over the course of a night, 300 or more sleep apnea episodes can occur (Schwab & others, 2005).

obstructive sleep apnea

(APP-nee-uh) A sleep disorder in which the person repeatedly stops breathing during sleep.

Obstructive sleep apnea disrupts the quality and quantity of a person’s sleep, causing daytime grogginess, poor concentration, memory and learning problems, and irritability (Weaver & George, 2005). Sleep apnea can also cause physical health problems, including weight gain, high blood pressure, and diabetes. Although OSA can occur in any age group, including small children, it becomes more common as people age. It is also more common in men than women.

Sleep apnea can often be treated with lifestyle changes, such as avoiding alcohol or losing weight (Hoffstein, 2005; Powell & others, 2005). Moderate to severe cases of sleep apnea are usually treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), using a device that increases air pressure in the throat so that the airway remains open (Grunstein, 2005).

Narcolepsy

BLURRING THE BOUNDARIES BETWEEN SLEEP AND WAKEFULNESS

Even with adequate nighttime sleep, people with narcolepsy experience overwhelming bouts of excessive daytime sleepiness and brief, uncontrollable episodes of sleep. These involuntary sleep episodes, called sleep attacks or microsleeps, typically last from a few seconds to several minutes.

narcolepsy

(NAR-ko-lep-see) A sleep disorder characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness and brief lapses into sleep throughout the day.

Most people with narcolepsy—about 70 percent—experience regular episodes of cataplexy, which is the sudden loss of voluntary muscle control, lasting from several seconds to several minutes. Such episodes are usually triggered by a sudden, intense emotion, such as laughter, anger, fear, or surprise. In more severe episodes of cataplexy, the person may completely lose muscle control, knees buckling as he or she collapses. Although unable to move or speak, the person is conscious and aware of what is happening.

cataplexy

A sudden loss of voluntary muscle strength and control that is usually triggered by an intense emotion.

The Parasomnias

UNDESIRED AROUSAL OR ACTIONS DURING SLEEP

We tend to think of sleep as an “either/or” phenomenon—we are either asleep or we are awake. But as the parasomnias show, sometimes sleep and waking states overlap or “bleed” into one another (Colwell, 2011; Mahowald & Schenk, 2005). In the parasomnias, some parts of the brain—like those involved in judging, thinking, or forming new memories—are asleep, but other, more primitive parts of the brain become activated (Cartwright, 2010). The brain is partially awake—awake enough to carry out the actions, but not awake enough to be consciously aware of performing the actions (Cartwright, 2010).

The parasomnias are a collection of sleep disorders that are characterized by undesirable physical arousal, behaviors, or events during sleep or sleep transitions (Mahowald & Schenk, 2005; Schenck, 2007). A key characteristic of all of the parasomnias is first, the lack of awareness while performing the actions and second, total amnesia for the behaviors or events upon awakening.

Parasomnias occur during NREM stages 3 and 4 slow-wave sleep during the first half of a night’s sleep. They can be triggered by a wide range of stimuli, including sleep deprivation, stress, erratic sleep schedules, sleeping medications, stimulants, pregnancy, and tranquilizers.

The parasomnias were once thought to be extremely rare, especially in adults. However, sleep researchers have discovered that some parasomnias—like sleeptalking, described on page 141, and sleepwalking—are relatively common (Bjorvatn & others, 2010). We’ll look at some specific parasomnias next.

SLEEP TERRORS

Also called night terrors, sleep terrors begin with a sharp increase in physiological arousal—restlessness, sweating, and a racing heart. The person abruptly sits up in bed and may let out a panic-stricken scream. Sleep terrors usually involve the terrifying sensation that one is being choked, crushed, or is falling. Although the sufferer may appear to be awake, he is terrified and disoriented, and usually impossible to calm (Mahowald & Schenck, 2005). Sleep terrors are most common in children, but a small percentage of adults also experience them.

sleep terrors

A sleep disturbance characterized by an episode of increased physiological arousal, intense fear and panic, frightening hallucinations, and no recall of the episode the next morning; typically occurs during stage 3 or stage 4 NREM sleep; also called night terrors.

SLEEPWALKING AND OTHER COMPLEX BEHAVIORS DURING SLEEP

The Prologue story about Scott described several key features of another parasomnia—sleepwalking, or somnambulism. Surprisingly, a sleepwalker can engage in elaborate and complicated behaviors, such as unlocking locks, opening windows, dismantling equipment, using tools, and even driving. Recall that Scott’s attack had occurred early in the night, shortly after he had “crashed,” or fallen asleep, as is most commonly the case with sleepwalking. There was no motivation for the attack, and as is characteristic of the parasomnias, he had no memory of it when he was awakened by the police (Cartwright, 2004).

sleepwalking

A sleep disturbance characterized by an episode of walking or performing other actions during stage 3 or stage 4 NREM sleep; also called somnambulism.

MYTH  SCIENCE

SCIENCE

Is it true true that it can be dangerous to wake a sleepwalker?

Although the behavior of most sleepwalkers is pretty benign, some, like Scott, can react aggressively if touched or interrupted (Cartwright, 2004, 2007, 2010; Pressman, 2007). It’s difficult to rouse sleepwalkers from deep sleep. Even if you do succeed in waking them, they are usually confused and have no memory of sleepwalking.

However, without realizing what they are doing, some sleepwalkers can respond aggressively, even violently, if touched. As described in the Prologue, Scott reacted violently to being interrupted while sleepwalking at least once while he was growing up, and his attack on his wife may have been caused by her trying to wake him up and guide him back to the house. In most cases, though, sleepwalkers respond to verbal suggestions and can be gently led back to bed without incident.

Sleepwalking is also involved in sleep-related eating disorder, which involves sleepwalking nightly to the kitchen, eating compulsively, and then awakening the next morning with no memory of having done so. Although sweet-tasting foods like candy or cake are most commonly consumed, the sleepwalker can also voraciously eat bizarre items, like raw bacon, dry pancake mix, salt sandwiches, coffee grounds, or cat food sandwiches. Interestingly, alcoholic beverages are hardly ever consumed during a sleepeating episode.

sleep-related eating disorder (SRED)

A sleep disorder in which the sleeper will sleepwalk and eat compulsively.

Also called sexsomnia, sleepsex involves abnormal sexual behaviors and experiences during sleep. Without realizing what they are doing, sleepers initiate some kind of sexual behavior, such as masturbation, groping or fondling their bed partner’s genitals, or even sexual intercourse (Trajanovic & Shapiro, 2010). Although sometimes described as loving or playful, more often sleepsex behavior is characterized as “robotic,” aggressive, and impersonal. Whether affectionate or forceful, sleepsex behavior is usually depicted as being out of character with the individual’s sexual behavior when awake (Schenck & others, 2007). As is the case in other parasomnias, the person typically has no memory of his actions the next day (Schenck, 2007).

sleepsex

A sleep disorder involving abnormal sexual behaviors and experiences during sleep; also called sexsomnia.

For more information about sleep disorders, visit the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s Web site, www.SleepEducation.com, or the National Sleep Foundation’s Web site, www.SleepFoundation.org.

CONCEPT REVIEW 4.2

Sleep Disorders and Dreams

1. Lisa suddenly sat up in bed and started screaming and struggling with the blankets. Although her eyes were open, she didn’t seem aware of her surroundings. After a few minutes, she fell back asleep. In the morning she remembered nothing of the incident. Lisa was probably in _____________________ sleep and experiencing a _____________________.

| A. | stage 4 NREM; sleep terror |

| B. | stage 1 NREM; hypnagogic hallucination |

| C. | REM; nightmare |

| D. | REM; sleep terror |

2. Mrs. Johnson is unable to sleep because her husband snores so loudly. He snorts as though he is gulping for air throughout the night, especially when he sleeps on his back. During the day Mr. Johnson is constantly tired. Mr. Johnson is probably suffering from _____________________.

| A. | insomnia |

| B. | sleep terrors |

| C. | narcolepsy |

| D. | obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) |

3. The night before an important job interview, Madison doesn’t sleep well. Each time she briefly awakens, the vague, thought-like imagery filling her mind is that of rehearsing details she wants to remember to say during the interview. These ruminations during sleep represent _____________________.

| A. | dreams |

| B. | nightmares |

| C. | parasomnias |

| D. | sleep thinking |

4. During psychotherapy sessions, Jake’s therapist asks him to describe his dreams in detail so that the therapist can help him uncover the hidden meaning of the dream images. Jake is describing the _____________________ content of his dreams. The therapist is trying to decipher the _____________________ content of Jake’s dreams.

| A. | lucid; circadian |

| B. | manifest; latent |

| C. | activated; synthesized |

| D. | restorative; adaptive |

5. According to the activation-synthesis model, dreams are _____________________.

| A. | meaningless |

| B. | symbolic representations of repressed wishes |

| C. | the subjective awareness of the brain’s internally generated signals during sleep |

| D. | produced by newly consolidated memories |

Test your understanding of Sleep Disorders with

.

.