5.2 Classical Conditioning: ASSOCIATING STIMULI

KEY THEME

Classical conditioning is a process of learning associations between stimuli.

KEY QUESTIONS

How did Pavlov discover and investigate classical conditioning?

How does classical conditioning occur?

What factors can affect classical conditioning?

One of the major contributors to the study of learning was not a psychologist but a Russian physiologist who was awarded a Nobel Prize for his work on digestion (Miyata, 2009). Ivan Pavlov was a brilliant scientist who directed several research laboratories in St. Petersburg, Russia, at the turn of the twentieth century. Pavlov’s involvement with psychology began as a result of an observation he made while investigating the role of saliva in digestion, using dogs as his experimental subjects.

In order to get a dog to produce saliva, Pavlov (1904) put food on the dog’s tongue. After he had worked with the same dog for several days in a row, Pavlov noticed something curious. The dog began salivating before Pavlov put the food on its tongue. In fact, the dog began salivating when Pavlov entered the room or even at the sound of his approaching footsteps. But salivating is a reflex—a largely involuntary, automatic response to an external stimulus. (As we’ve noted in previous chapters, a stimulus is anything perceptible to the senses, such as a sight, sound, smell, touch, or taste.) The dog should salivate only after the food is presented, not before. Why would the reflex occur before the stimulus was presented? What was causing this unexpected behavior?

If you own a dog, you’ve probably observed the same basic phenomenon. Your dog gets excited and begins to slobber when you shake a box of dog biscuits, even before you’ve given him a doggie treat. In everyday language, your pet has learned to anticipate food in association with some signal—namely, the sound of dog biscuits rattling in a box.

MYTH !lhtriangle! SCIENCE

Is it true that Pavlov taught dogs to drool at the sound of a bell by rewarding them with food?

Pavlov’s extraordinary gifts as a researcher enabled him to recognize the important implications of what had at first seemed a problem—a reflex (salivation) that occurred before the appropriate stimulus (food) was presented. He also had the discipline to systematically study how such associations are formed. In fact, Pavlov abandoned his research on digestion and devoted the remaining 30 years of his life to investigating different aspects of this phenomenon. Let’s look at what he discovered in more detail.

Principles of Classical Conditioning

The process of conditioning that Pavlov discovered was the first to be extensively studied in psychology. Thus, it’s called classical conditioning (Hilgard & Marquis, 1940). It’s also known as Pavlovian conditioning (Lattal, 2013). Classical conditioning deals with behaviors that are elicited automatically by some stimulus. Elicit means “draw out” or “bring forth.” That is, the stimulus doesn’t produce a new behavior but rather causes an existing behavior to occur.

classical conditioning

The basic learning process that involves repeatedly pairing a neutral stimulus with a response-producing stimulus until the neutral stimulus elicits the same response.

Classical conditioning almost always involves some kind of reflexive behavior. Remember, a reflex is a relatively simple, unlearned behavior, governed by the nervous system, that occurs automatically when the appropriate stimulus is presented. In Pavlov’s (1904) original studies of digestion, the dogs salivated reflexively when food was placed on their tongues. But when the dogs began salivating in response to the sight of Pavlov or to the sound of his footsteps, a new, learned stimulus elicited the salivary response. Thus, in classical conditioning, a new stimulus–

How does this kind of learning take place? Essentially, classical conditioning is a process of learning an association between two stimuli. Classical conditioning involves pairing a neutral stimulus (e.g., the sight of Pavlov) with an unlearned, natural stimulus (food in the mouth) that automatically elicits a reflexive response (the dog salivates). If the two stimuli (Pavlov + food) are repeatedly paired, eventually the neutral stimulus (Pavlov) elicits the same basic reflexive response as the natural stimulus (food)—even in the absence of the natural stimulus. So, when the dog in the laboratory started salivating at the sight of Pavlov before the food was placed on its tongue, it was because the dog had formed a new, learned association between the sight of Pavlov and the food.

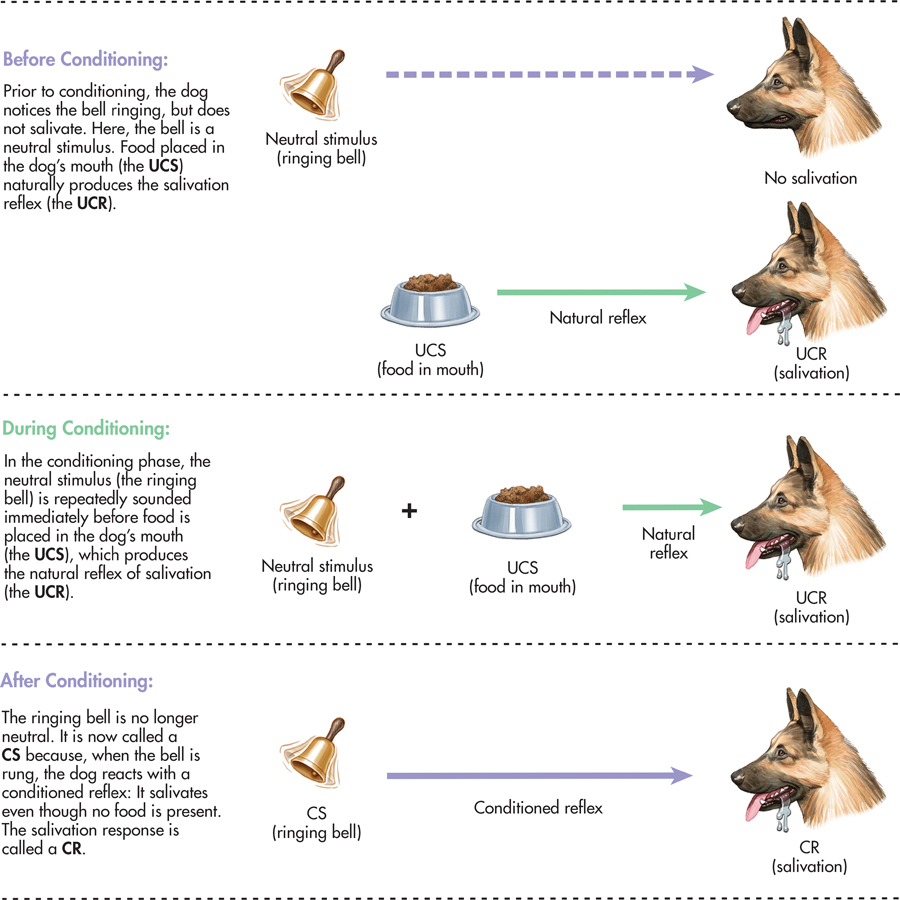

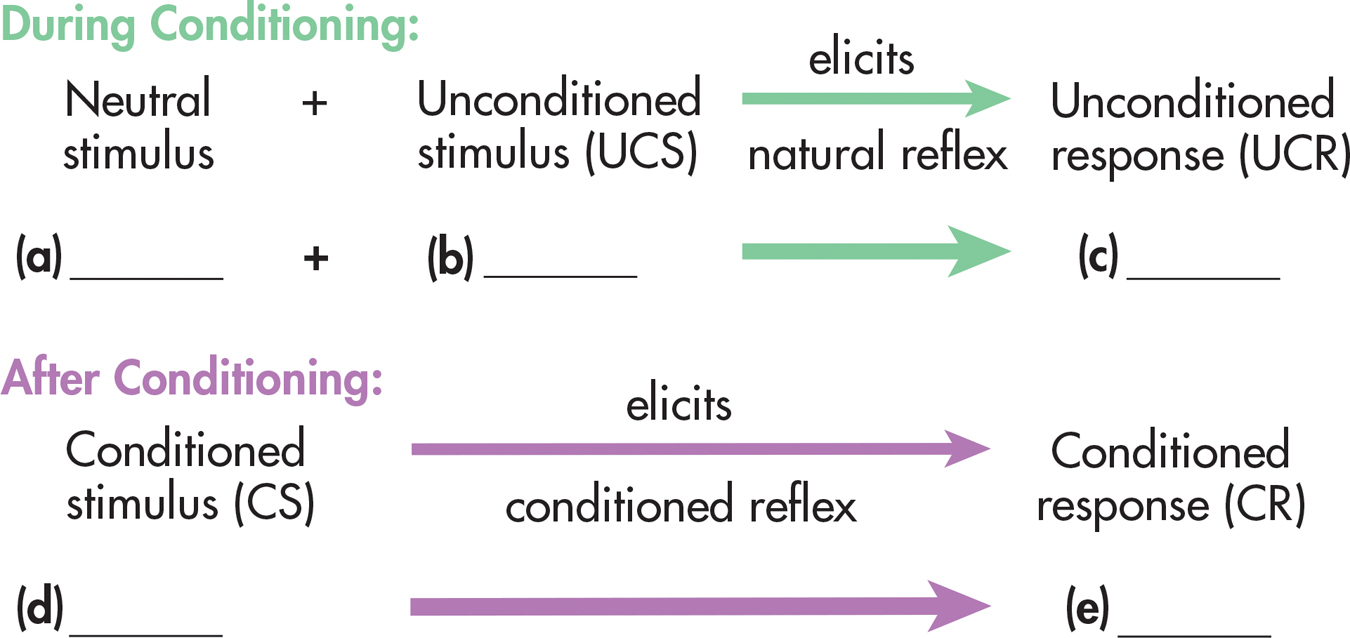

Pavlov used special terms to describe each element of the classical conditioning process. The natural stimulus that reflexively produces a response without prior learning is called the unconditioned stimulus (abbreviated UCS). In this example, the unconditioned stimulus is the food in the dog’s mouth. The unlearned, reflexive response is called the unconditioned response (or UCR). The unconditioned response is the dog’s salivation.

unconditioned stimulus (UCS)

The natural stimulus that reflexively elicits a response without the need for prior learning.

unconditioned response (UCR)

The unlearned, reflexive response that is elicited by an unconditioned stimulus.

To learn more about his discovery, Pavlov (1927) controlled the stimuli that preceded the presentation of food. For example, in one set of experiments, he used a bell as a neutral stimulus—neutral because dogs don’t normally salivate to the sound of a ringing bell. Pavlov first rang the bell and then gave the dog food. After this procedure was repeated several times, the dog began to salivate when the bell was rung, before the food was put in its mouth. At that point, the dog was classically conditioned to salivate to the sound of a bell alone. That is, the dog had learned a new association between the sound of the bell and the presentation of food.

Pavlov called the sound of the bell the conditioned stimulus. The conditioned stimulus (or CS) is the stimulus that is originally neutral but comes to elicit a reflexive response. He called the dog’s salivation to the sound of the bell the conditioned response (or CR), which is the learned reflexive response to a previously neutral stimulus. The steps of Pavlov’s conditioning process are outlined in FIGURE 5.1.

conditioned stimulus (CS)

A formerly neutral stimulus that acquires the capacity to elicit a reflexive response.

conditioned response (CR)

The learned, reflexive response to a conditioned stimulus.

Classical conditioning terminology can be confusing. You may find it helpful to think of the word conditioned as having the same meaning as “learned.” Thus, the “conditioned stimulus” refers to the “learned stimulus,” the “unconditioned response” refers to the “unlearned response,” and so forth.

It’s also important to note that, in this case, the unconditioned response and the conditioned response describe essentially the same behavior—the dog’s salivating. Which label is applied depends on which stimulus elicits the response. If the dog is salivating in response to a natural stimulus that was not acquired through learning, the salivation is an unconditioned response. If, however, the dog has learned to salivate to a neutral stimulus that doesn’t normally produce the automatic response, the salivation is a conditioned response.

Question 5.2

fz1F25sBAx1YrMrvivW8PpMbJSHGeQtUGRUTx/slgkT2O63nHvN4uHhriPmQMhiUPhBqqiESnhf1cNlTUKwPbcMcoWJCEJJu4uS2YWBcLct5ByNtZb8hW+sRQ1bisw/AZ0utsI2THuNm8DjPToh36CCbGbvfvLs6klFoA2xv+DQaCOVTnQPdh4YvEgXnTVrsyYpEOEknD+jCg16RXTBq6dpYckmR9Zz+gfzL56vjz1M9YHkAv8GwPGJgT7xnJQfTXPnBnQ==Factors That Affect Conditioning

Over the three decades that Pavlov (1928) spent studying classical conditioning, he discovered many factors that could affect the strength of the conditioned response (Bitterman, 2006). For example, he discovered that the more frequently the conditioned stimulus and the unconditioned stimulus were paired, the stronger was the association between the two.

Pavlov also discovered that the timing of stimulus presentations affected the strength of the conditioned response. He found that conditioning was most effective when the conditioned stimulus was presented immediately before the unconditioned stimulus. In his early studies, Pavlov found that a half-second was the optimal time interval between the onset of the conditioned stimulus and the beginning of the unconditioned stimulus. Later, Pavlov and other researchers found that the optimal time interval could vary in different conditioning situations but was rarely more than a few seconds.

STIMULUS GENERALIZATION AND DISCRIMINATION

Pavlov (1927) noticed that once a dog was conditioned to salivate to a particular stimulus, new stimuli that were similar to the original conditioned stimulus could also elicit the conditioned salivary response. For example, Pavlov conditioned a dog to salivate to a low-pitched tone. When he sounded a slightly higher-pitched tone, the conditioned salivary response would also be elicited. Pavlov called this phenomenon stimulus generalization. Stimulus generalization occurs when stimuli that are similar to the original conditioned stimulus also elicit the conditioned response, even though they have never been paired with the unconditioned stimulus. If you own a dog that tends to salivate and get excited when you shake a box of dog biscuits, you may have noticed that your dog also drools when you shake a bag of cat food. If so, that would be an example of stimulus generalization.

stimulus generalization

The occurrence of a learned response not only to the original stimulus but to other, similar stimuli as well.

Just as a dog can learn to respond to similar stimuli, so it can learn the opposite—to distinguish between similar stimuli. For example, Pavlov repeatedly gave a dog some food following a high-pitched tone but did not give the dog any food following a low-pitched tone. The dog learned to distinguish between the two tones, salivating to the high-pitched tone but not to the low-pitched tone. This phenomenon, stimulus discrimination, occurs when a particular conditioned response is made to one stimulus but not to other, similar stimuli. So, if your dog eventually stops salivating when you shake a bag of cat food, stimulus discrimination has taken place.

stimulus discrimination

The occurrence of a learned response to a specific stimulus but not to other, similar stimuli.

HIGHER ORDER CONDITIONING

In further studies of his classical conditioning procedure, Pavlov (1927) found that a conditioned stimulus could itself function as an unconditioned stimulus in a new conditioning trial. This phenomenon is called higher order conditioning or second-order conditioning. Pavlov paired a ticking metronome with food until the sound of the ticking metronome became established as a conditioned stimulus. Then Pavlov repeatedly paired a new unconditioned stimulus, a black square, with the ticking metronome—but no food. After several pairings, would the black square alone produce salivation? It did, even though the black square had never been directly paired with food. The black square had become a new conditioned stimulus, simply by being repeatedly paired with the first conditioned stimulus: the ticking metronome. Like the first conditioned stimulus, the black square produced the conditioned response: salivation.

higher order conditioning

(also called second-order conditioning) A procedure in which a conditioned stimulus from one learning trial functions as the unconditioned stimulus in a new conditioning trial; the second conditioned stimulus comes to elicit the conditioned response, even though it has never been directly paired with the unconditioned stimulus.

It is important to note that in higher order conditioning, the new conditioned stimulus has never been paired with the unconditioned stimulus. The new conditioned stimulus acquires its ability to produce the conditioned response by virtue of being paired with the first conditioned stimulus (Hussaini & others, 2007; Jara & others, 2006).

Consider this example: Like most children, your authors Don and Sandy’s daughter, Laura, received several rounds of immunizations when she was an infant. Each painful injection (the UCS) elicited distress and made her cry (the UCR). After only the second vaccination, Laura developed a strong classically conditioned response—just the sight of a nurse’s white uniform (the CS) triggered an emotional outburst of fear and crying (the CR). Interestingly, Laura’s conditioned fear generalized to a wide range of white uniforms, including a pharmacist’s white smock, a veterinarian’s white lab coat, and even the white jacket of a cosmetics saleswoman in a department store.

To illustrate higher order conditioning, imagine that baby Laura reacted fearfully when she saw a white-jacketed cosmetics saleswoman in a department store. Imagine further that the saleswoman compounded Laura’s reaction by spraying her mother, Sandy, with a new perfume fragrance and handing Sandy a free perfume sample to take home. If Laura responded with fear the next time she smelled the fragrance, higher order conditioning would have taken place. The perfume scent had never been paired with the original UCS, the painful injection. The scent became a new CS by virtue of being paired with the first CS, the white jacket.

EXTINCTION AND SPONTANEOUS RECOVERY

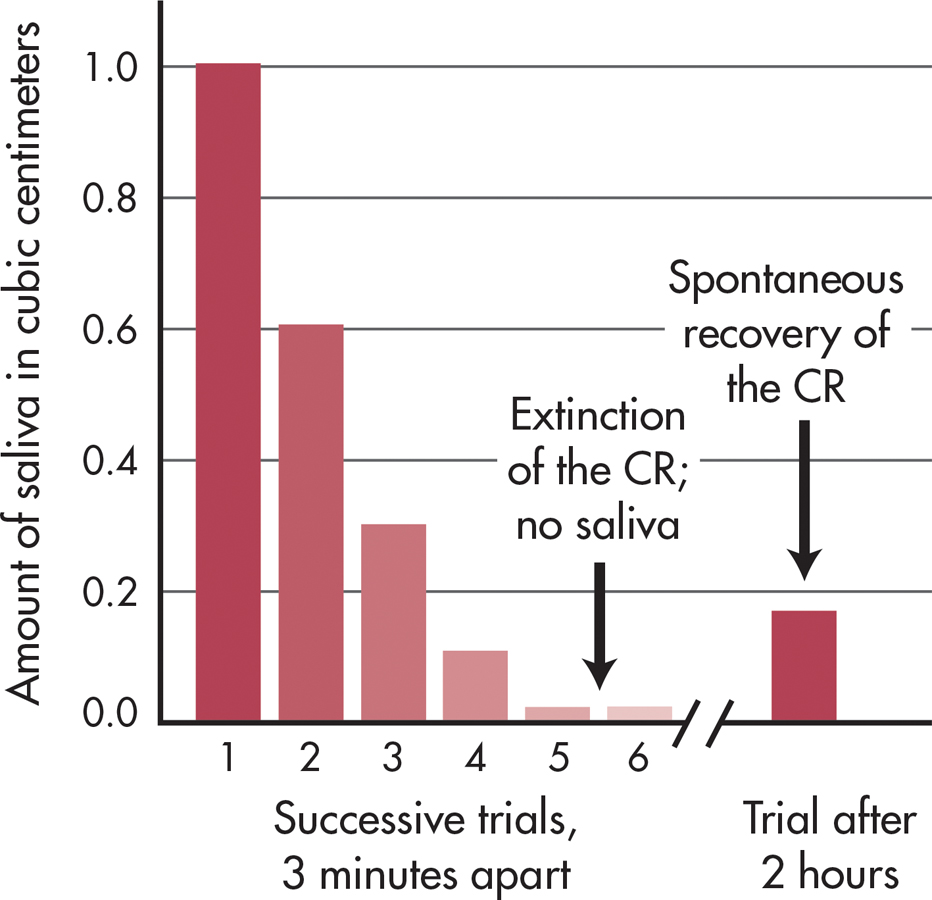

Once learned, can conditioned responses be eliminated? Pavlov (1927) found that conditioned responses could be gradually weakened. If the conditioned stimulus (the ringing bell) was repeatedly presented without being paired with the unconditioned stimulus (the food), the conditioned response seemed to gradually disappear. Pavlov called this process of decline and eventual disappearance of the conditioned response extinction.

extinction (in classical conditioning)

The gradual weakening and apparent disappearance of conditioned behavior. In classical conditioning, extinction occurs when the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus.

Pavlov also found that the dog did not simply return to its unconditioned state following extinction (see FIGURE 5.2). If the animal was allowed a period of rest (such as a few hours) after the response was extinguished, the conditioned response would reappear when the conditioned stimulus was again presented. This reappearance of a previously extinguished conditioned response after a period of time without exposure to the conditioned stimulus is called spontaneous recovery. The phenomenon of spontaneous recovery demonstrates that extinction is not unlearning. That is, the learned response may seem to disappear, but it is not eliminated or erased (Archbold & others, 2010; Rescorla, 2001).

spontaneous recovery

The reappearance of a previously extinguished conditioned response after a period of time without exposure to the conditioned stimulus.

CONCEPT REVIEW 5.1

Elements of Classical Conditioning

For each of the following examples, use the diagram in the column on the right to help identify the neutral stimulus, UCS, UCR, CS, and CR.

Question 5.3

| 1. | When Cindy’s four-month-old infant cried, she would begin breast-feeding him. One evening, Cindy went to a movie with her husband, leaving her baby at home with a sitter. When an infant in the theater began to cry, Cindy experienced the “let-down” reflex, and a few drops of milk stained her new silk blouse. |

(a) baby’s cry (b) nursing baby (c) let-down reflex, breast milk flows (d) baby’s cry (e) let-down reflex, breast milk flows

Question 5.4

| 2. | After swimming in the lake near his home one day, Frank emerged from the water covered with slimy, bloodsucking leeches all over his legs and back. He was revolted as he removed the leeches. Now, every time he passes the lake, Frank shudders in disgust. |

(a) lake (b) leeches (c) disgust (d) lake (e) disgust

Question 5.5

| 3. | Every time two-year-old Jodie heard the doorbell ring, she raced to open the front door. On Halloween night, Jodie answered the doorbell and encountered a scary monster with nine flashing eyes. Jodie screamed in fear and ran away. Now Jodie screams and hides whenever the doorbell rings. |

(a) doorbell (b) scary monster (c) fear (d) doorbell (e) fear

From Pavlov to Watson: THE FOUNDING OF BEHAVIORISM

KEY THEME

Behaviorism was founded by John Watson, who redefined psychology as the scientific study of behavior.

KEY QUESTIONS

What were the fundamental assumptions of behaviorism?

How did Watson use classical conditioning to explain and produce conditioned emotional responses?

How did Watson apply classical conditioning techniques to advertising?

Over the course of three decades, Pavlov systematically investigated different aspects of classical conditioning. Pavlov believed he had discovered the mechanism by which all learning occurs, but he did not apply his findings to human behavior. That task was to be taken up by a young psychologist, John B. Watson.

Watson believed that the early psychologists were following the wrong path by focusing on the study of subjective mental processes, which could not be objectively observed (Berman & Lyons, 2007). Instead, Watson (1913) strongly advocated that psychology should be redefined as the scientific study of behavior, which, unlike mental processes, could be objectively observed. As described in Chapter 1, Watson founded a new school, or approach, in psychology, called behaviorism. Pavlov’s discovery of the conditioned reflex provided the model Watson had been seeking to investigate and explain human behavior (Evans & Rilling, 2000; Watson, 1916).

behaviorism

School of psychology and theoretical viewpoint that emphasizes the study of observable behaviors, especially as they pertain to the process of learning.

Let us limit ourselves to things that can be observed, and formulate laws concerning only those things. Now what can we observe? We can observe behavior—what the organism does or says.

—John B. Watson (1924)

Watson believed that virtually all human behavior is a result of conditioning and learning—that is, due to past experience and environmental influences. In a characteristically bold statement, Watson (1924) proclaimed:

I should like to go one step further now and say, “Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select—doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors.” I am going beyond my facts and I admit it, but so have the advocates of the contrary and they have been doing it for many thousands of years.

Needless to say, Watson never actually carried out such an experiment, and his boast clearly exaggerated the role of the environment to make his point. Nevertheless, Watson’s influence on psychology cannot be overemphasized. Behaviorism was to dominate psychology in the United States for more than 50 years. And, as you’ll see in the next section, Watson did carry out a famous and controversial experiment to demonstrate how human behavior could be classically conditioned.

Conditioned Emotional Reactions

Watson believed that, much as Pavlov’s dogs reflexively salivated to food, human emotions could be thought of as reflexive responses involving the muscles and glands. In studies with infants, Watson (1919) identified three emotions that he believed represented inborn and natural unconditioned reflexes—fear, rage, and love. According to Watson, each of these innate emotions could be reflexively triggered by a small number of specific stimuli. For example, he found two stimuli that could trigger the reflexive fear response in infants: a sudden loud noise and a sudden dropping motion.

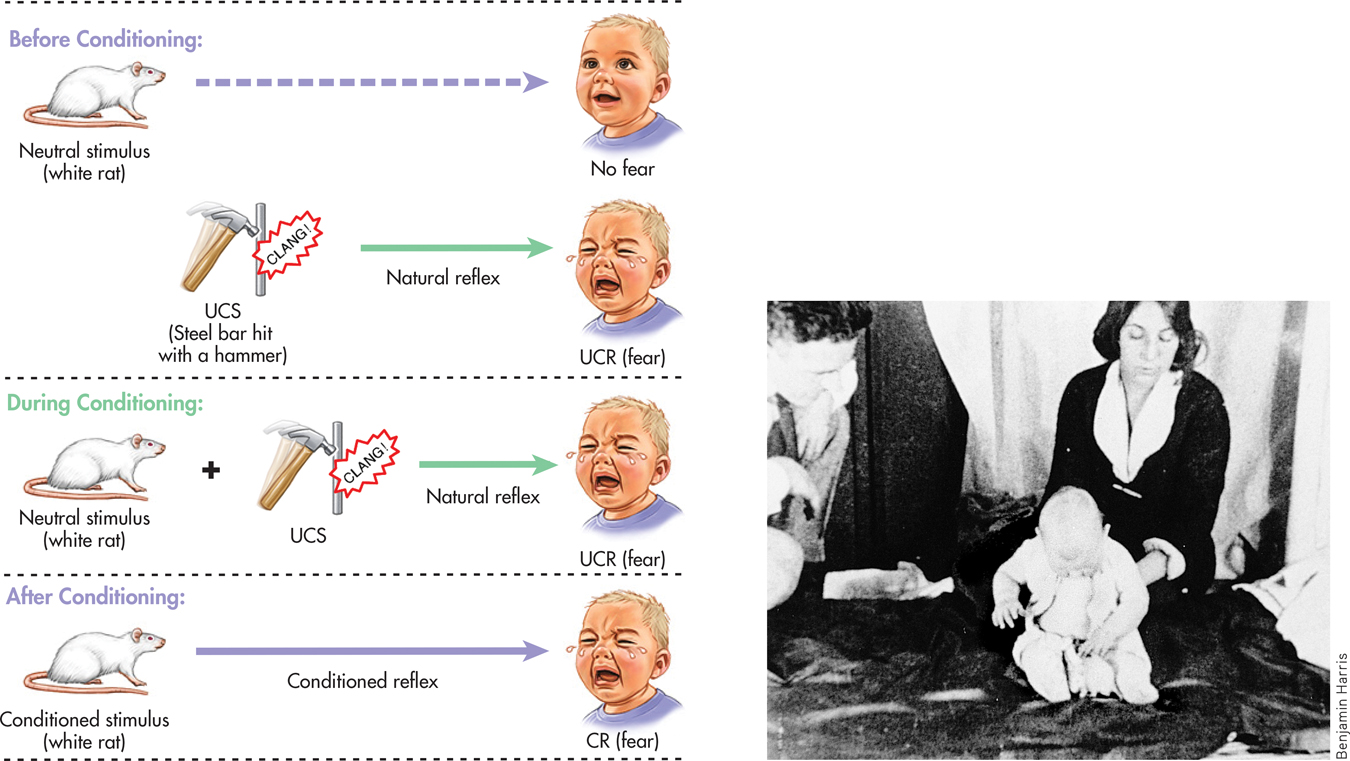

THE FAMOUS CASE OF LITTLE ALBERT

Watson’s interest in the role of classical conditioning in emotions set the stage for one of the most famous and controversial experiments in the history of psychology. In 1920, Watson and a graduate student named Rosalie Rayner set out to demonstrate that classical conditioning could be used to deliberately establish a conditioned emotional response in a human subject. Their subject was a baby, whom they called “Albert B.,” but who is now more popularly known as “Little Albert.” Little Albert lived with his mother in the Harriet Lane Hospital in Baltimore, where his mother was employed.

Watson and Rayner (1920) first assessed Little Albert when he was only nine months old. Little Albert was a healthy, unusually calm baby who showed no fear when presented with a tame white rat, a rabbit, a dog, and a monkey. He was also unafraid of cotton, masks, and even burning newspapers! But, as with other infants whom Watson had studied, fear could be triggered in Little Albert by a sudden loud sound—clanging a steel bar behind his head. In this case, the sudden clanging noise is the unconditioned stimulus, and the unconditioned response is fear.

Two months after their initial assessment, Watson and Rayner attempted to condition Little Albert to fear the tame white rat (the conditioned stimulus). Watson stood behind Little Albert. Whenever Little Albert reached toward the rat, Watson clanged the steel bar with a hammer. Just as before, of course, the unexpected loud CLANG! (the unconditioned stimulus) startled and scared the daylights out of Little Albert (the unconditioned response).

During the first conditioning session, Little Albert experienced two pairings of the white rat with the loud clanging sound. A week later, he experienced five more pairings of the two stimuli. After only these seven pairings of the loud noise and the white rat, the white rat alone triggered the conditioned response—extreme fear—in Little Albert (see FIGURE 5.3).

Watson and Rayner also found that stimulus generalization had taken place. Along with fearing the rat, Little Albert was now afraid of other furry animals, including a dog and a rabbit. He had even developed a classically conditioned fear response to a variety of fuzzy objects—a sealskin coat, cotton, Watson’s hair, and a white-bearded Santa Claus mask!

Although the Little Albert study has attained legendary status in psychology, it had several problems (Harris, 1979, 2011; Paul & Blumenthal, 1989). One criticism is that the experiment was not carefully designed or conducted. For example, Albert’s fear and distress were not objectively measured but were subjectively evaluated by Watson and Rayner.

IN FOCUS

Watson, Classical Conditioning, and Advertising

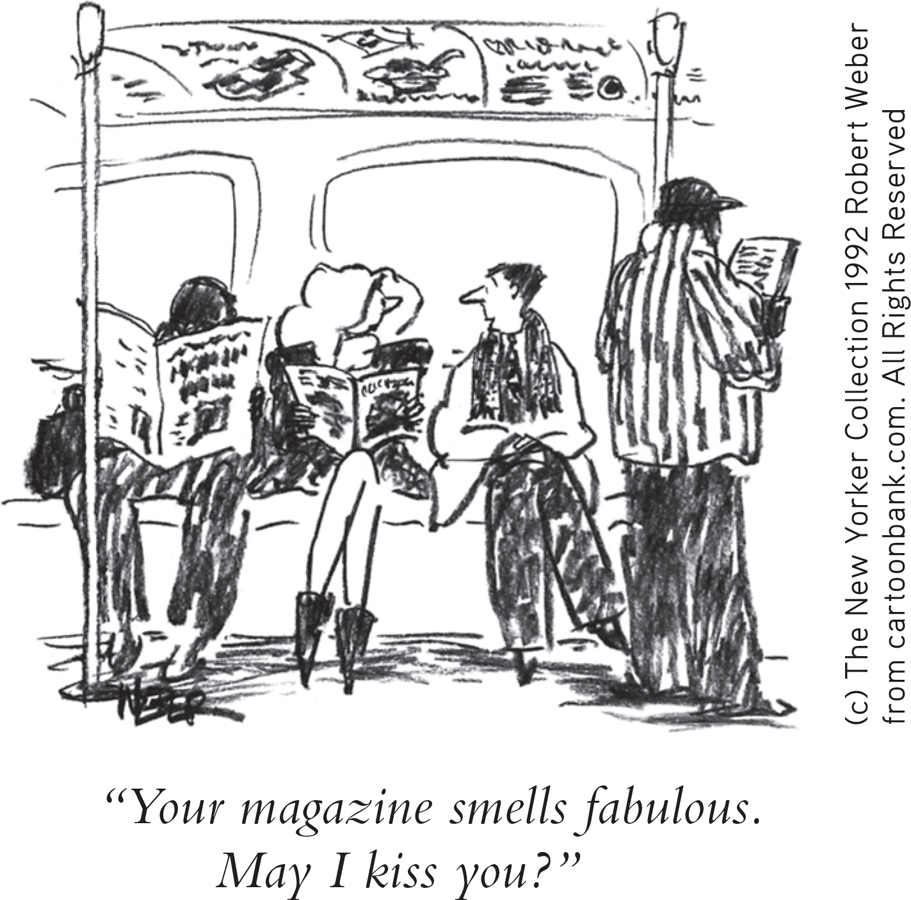

From shampoos to soft drinks, advertising campaigns often use sexy models to promote their products. Today, we take this advertising tactic for granted. But it’s actually yet another example of Watson’s influence.

Shortly after the Little Albert experiment, Watson’s wife discovered that he was having an affair with his graduate student Rosalie Rayner. Following a scandalous and highly publicized divorce, Watson was fired from his academic position. Despite his international fame as a scientist, no other university would hire him (Benjamin & others, 2007). Banned from academia, Watson married Rayner and joined the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency (Buckley, 1989; Carpintero, 2004).

Watson was a pioneer in the application of classical conditioning principles to advertising. “To make your consumer react,” Watson told his colleagues at the ad agency, “tell him something that will tie him up with fear, something that will stir up a mild rage, that will call out an affectionate or love response, or strike at a deep psychological or habit need” (quoted in Buckley, 1982).

Watson applied this technique to ad campaigns for Johnson & Johnson Baby Powder and Pebeco toothpaste in the 1920s. For the baby powder ad, Watson intentionally tried to stimulate an anxiety response in young mothers by creating doubts about their ability to care for their infants.

The Pebeco toothpaste campaign targeted the newly independent young woman who smoked. The ad raised the fear that attractiveness might be diminished by the effects of smoking—and Pebeco toothpaste was promoted as a way of increasing sexual attractiveness. One ad read, “Girls! Don’t worry any more about smoke-stained teeth or tobacco-tainted breath. You can smoke and still be lovely if you’ll just use Pebeco twice a day.” Watson also developed ad campaigns for Pond’s cold cream, Maxwell House coffee, and Camel cigarettes.

While Watson may have pioneered the strategy of associating products with “sex appeal,” modern advertising has taken this technique to an extreme. Similarly, some ad campaigns pair products with images of adorable babies, cuddly kittens, happy families, or other “natural” stimuli that elicit warm, emotional responses. If classical conditioning occurs, the product by itself will also elicit a warm, emotional response.

Are such procedures effective? In a word, yes. Attitudes toward a product or a particular brand can be influenced by advertising and marketing campaigns that use classical conditioning methods (W. Hofmann & others, 2010).

The experiment is also open to criticism on ethical grounds. Watson and Rayner (1920) did not extinguish Little Albert’s fear of furry animals and objects, even though they believed that such conditioned emotional responses would “persist and modify personality throughout life.” Such an experiment could not ethically be conducted today.

Whether Watson and Rayner had originally intended to extinguish the fear is not completely clear (see Paul & Blumenthal, 1989). Watson (1930) later wrote that he and Rayner could not try to eliminate Albert’s fear response because the infant had been adopted by a family in another city shortly after the experiment had concluded.

Generations of psychologists have wondered what happened to Little Albert. After years of detective work, psychologist Hall P. Beck and his colleagues (2009, 2010) identified Albert as Douglas Merritt, the son of a woman working at the hospital where the experiment was conducted. However, psychologist Russell A. Powell and his colleagues (2014) proposed a different candidate: Albert Barger, the infant son of another woman working at the hospital. Like Douglas Merritt, Albert Barger would have been the same age as the “Little Albert B.” in Watson and Rayner’s study. Unlike Douglas, however, who died at age 6 of a neurological disease, Albert lived to the ripe old age of 88.

You can probably think of situations, objects, or people that evoke a strong classically conditioned emotional reaction in you, such as fear or anger. For example, you might become classically conditioned to cues associated with a person whom you strongly dislike, such as a demeaning boss or an ex-lover. After repeated negative experiences (the UCS) with the person eliciting anger (the UCR), a wide range of cues can become conditioned stimuli (CSs)—the person’s name, the sight of the person, locations associated with the person, and so forth—and elicit a strong negative emotional reaction (the CR) in you. Just hearing the person’s name can send your heart rate and blood pressure soaring. Other emotional responses, such as feelings of fear, happiness, or sadness, can also be classically conditioned.

In this chapter’s Prologue, we saw that Erv became classically conditioned to feel anxious whenever he entered the attic. The attic (the original neutral stimulus) was coupled with being trapped in extreme heat (the UCS), which produced fear (the UCR). Following the episode, Erv found that going into the attic (now a CS) triggered mild fear and anxiety (the CR). Like Erv, many people experience a conditioned fear response to objects, situations, or locations that are associated with some kind of traumatic experience or event. In fact, despite their knowledge of classical conditioning, your authors are not immune to this effect (see photo).

Other Classically Conditioned Responses

Under the right conditions, virtually any automatic response can become classically conditioned. For example, some aspects of sexual responses can become classically conditioned, sometimes inadvertently. To illustrate, suppose that a neutral stimulus, such as the scent of a particular cologne, is regularly paired with the person with whom you are romantically involved. You, of course, are most aware of the scent when you are physically close to your partner in sexually arousing situations. After repeated pairings, the initially neutral stimulus—the particular cologne scent—can become a conditioned stimulus. Now, the scent of the cologne evokes feelings of romantic excitement or mild sexual arousal even in the absence of your lover or, in some cases, long after the relationship has ended. And, in fact, a wide variety of stimuli can become “sexual turn-ons” through classical conditioning.

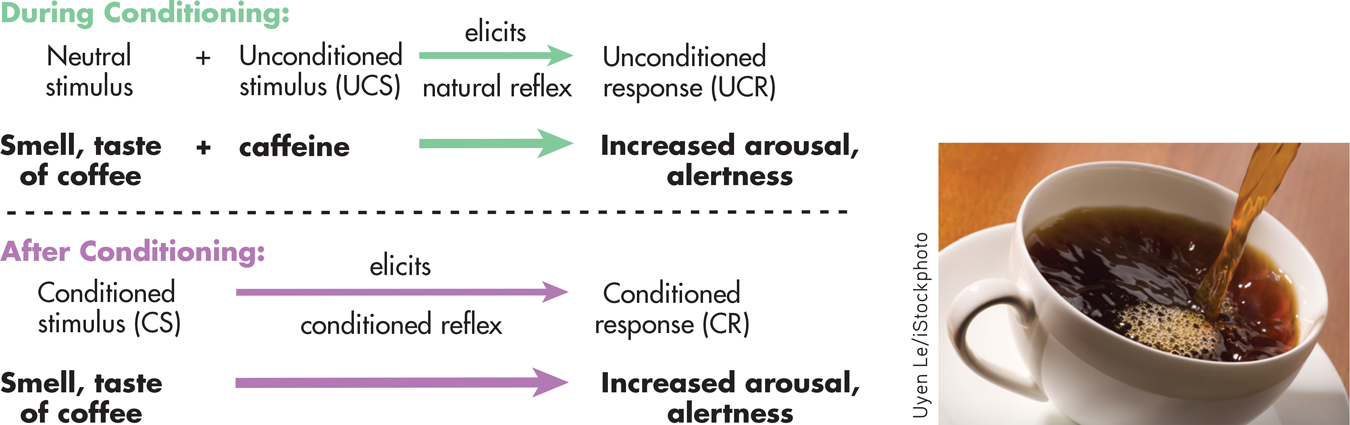

Classical conditioning can also influence drug responses. For example, if you are a regular coffee drinker, you may have noticed that you begin to feel more awake and alert after just a few groggy sips of your first cup of coffee in the morning. However, it takes at least 20 minutes for the caffeine from the coffee to reach significant levels in your bloodstream. If you’re feeling more awake before blood levels of caffeine rise, it’s probably because you’ve developed a classically conditioned response to the sight, smell, and taste of coffee (see FIGURE 5.4). Confirming that everyday experience, such conditioned responses to caffeine-associated stimuli have also been demonstrated experimentally (see Flaten & Blumenthal, 1999; Mikalsen & others, 2001).

Once this classically conditioned drug effect becomes well established, the smell or taste of coffee—even decaffeinated coffee—can trigger the conditioned response of increased arousal and alertness (Attwood & others, 2010).

Conditioned drug effects seem to be involved in at least some instances of placebo response (Benedetti & others, 2010; Stewart-Williams & Podd, 2004). Also called placebo effect, a placebo response occurs when an individual has a psychological and physiological reaction to what is actually a fake treatment or drug. We’ll discuss this phenomenon in more detail in Chapter 13.

placebo response

An individual’s psychological and physiological response to what is actually a fake treatment or drug; also called placebo effect.