5.4 Operant Conditioning: ASSOCIATING BEHAVIORS AND CONSEQUENCES

KEY THEME

Operant conditioning deals with the learning of active, voluntary behaviors that are shaped and maintained by their consequences.

KEY QUESTIONS

How did Edward Thorndike study the acquisition of new behaviors, and what conclusions did he reach?

What were B. F. Skinner’s key assumptions?

How are positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement similar, and how are they different?

Classical conditioning can help explain the acquisition of many learned behaviors, including emotional and physiological responses. However, recall that classical conditioning involves reflexive behaviors that are automatically elicited by a specific stimulus. Most everyday behaviors don’t fall into this category. Instead, they involve nonreflexive, or voluntary, actions that can’t be explained with classical conditioning.

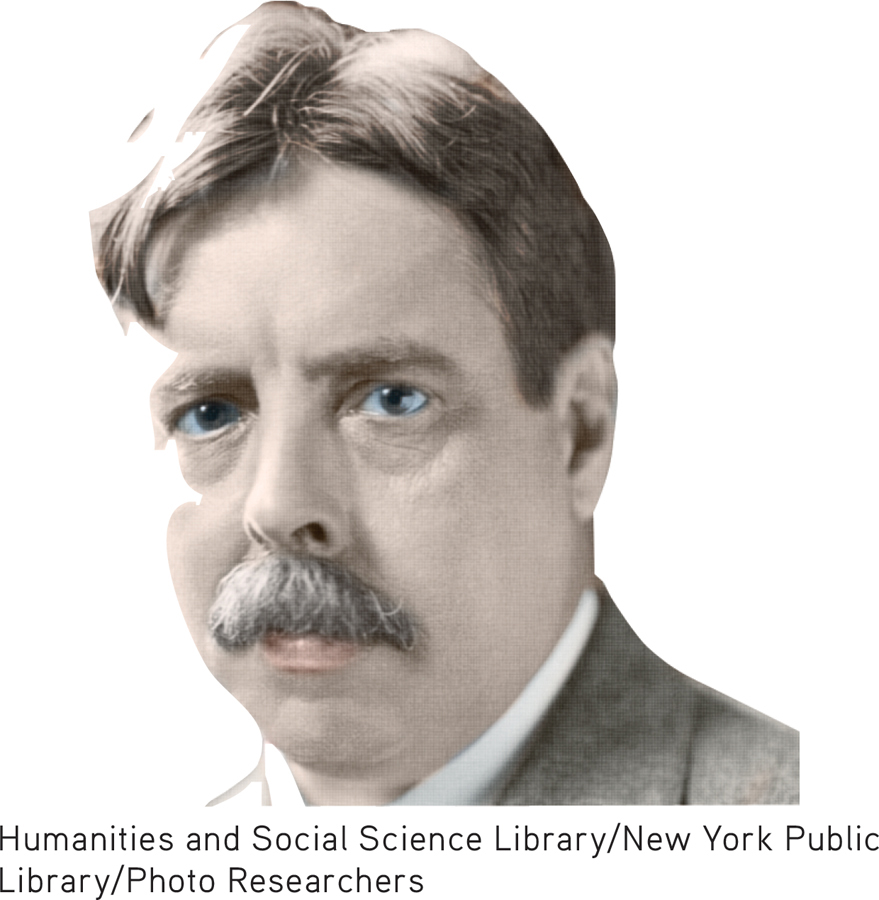

The investigation of how voluntary behaviors are acquired began with a young American psychology student named Edward L. Thorndike. A few years before Pavlov began his extensive studies of classical conditioning, Thorndike was using cats, chicks, and dogs to investigate how voluntary behaviors are acquired. Thorndike’s pioneering studies helped set the stage for the later work of another American psychologist named B. F. Skinner. It was Skinner who developed operant conditioning, another form of conditioning that explains how we acquire and maintain voluntary behaviors.

Thorndike and the Law of Effect

Edward L. Thorndike was the first psychologist to systematically investigate animal learning and how voluntary behaviors are influenced by their consequences. At the time, Thorndike was only in his early 20s and a psychology graduate student. He conducted his pioneering studies to complete his dissertation and earn his doctorate in psychology.

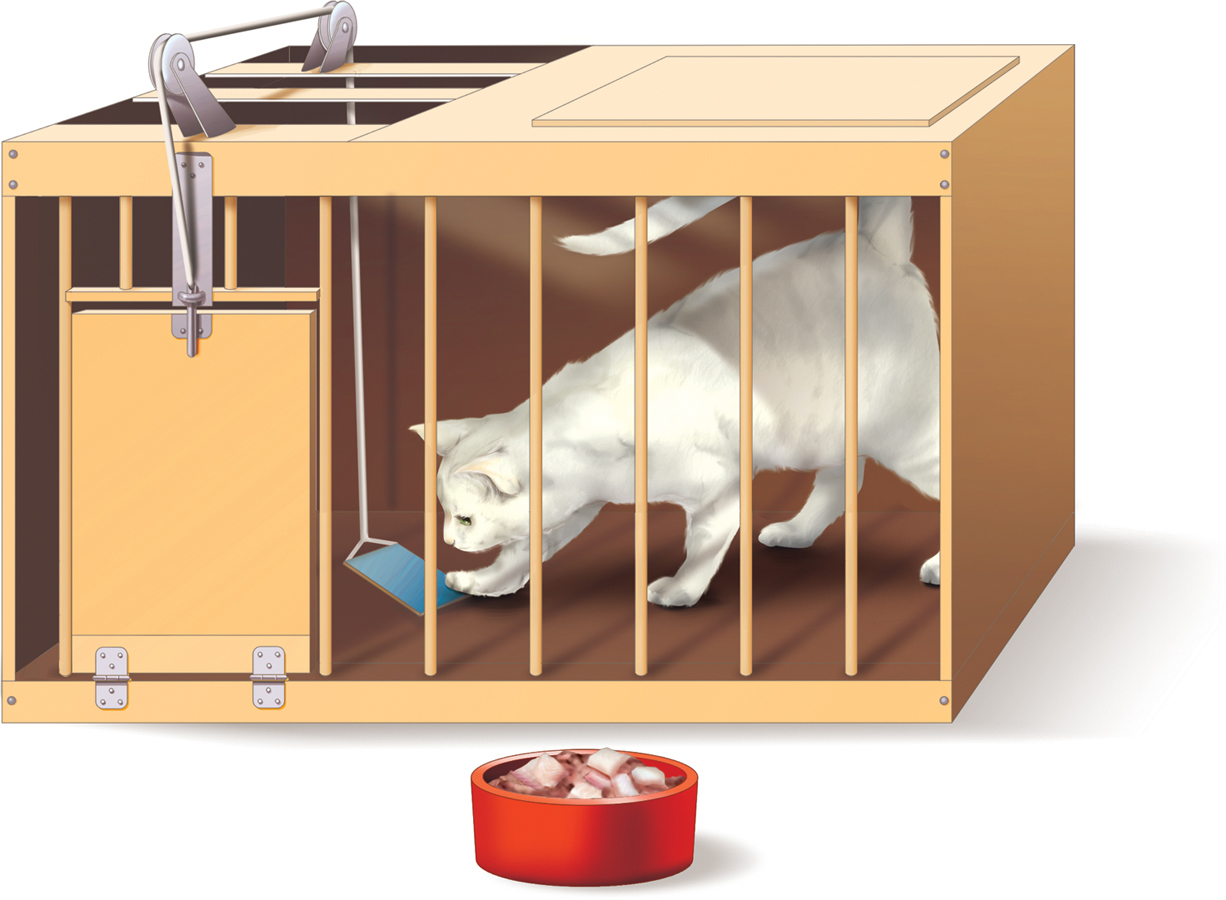

Thorndike’s dissertation focused on the issue of whether animals, like humans, use reasoning to solve problems (Dewsbury, 1998). In an important series of experiments, Thorndike (1898) put hungry cats in specially constructed cages that he called “puzzle boxes.” A cat could escape the cage by a simple act, such as pulling a loop or pressing a lever that would unlatch the cage door. A plate of food was placed just outside the cage, where the hungry cat could see and smell it.

Thorndike found that when the cat was first put into the puzzle box, it would engage in many different, seemingly random behaviors to escape. For example, the cat would scratch at the cage door, claw at the ceiling, and try to squeeze through the wooden slats (not to mention complain at the top of its lungs). Eventually, however, the cat would accidentally pull on the loop or step on the lever, opening the door latch and escaping the box. After several trials in the same puzzle box, a cat could get the cage door open very quickly.

Thorndike (1898) concluded that the cats did not display any humanlike insight or reasoning in unlatching the puzzle box door. Instead, he explained the cats’ learning as a process of trial and error (Chance, 1999). The cats gradually learned to associate certain responses with successfully escaping the box and gaining the food reward. According to Thorndike, these successful behaviors became “stamped in,” so that a cat was more likely to repeat these behaviors when placed in the puzzle box again. Unsuccessful behaviors were gradually eliminated.

Thorndike’s observations led him to formulate the law of effect: Responses followed by a “satisfying state of affairs” are “strengthened” and more likely to occur again in the same situation. Conversely, responses followed by an unpleasant or “annoying state of affairs” are “weakened” and less likely to occur again.

law of effect

Learning principle, proposed by Thorndike, in which responses followed by a satisfying effect become strengthened and are more likely to recur in a particular situation, while responses followed by a dissatisfying effect are weakened and less likely to recur in a particular situation.

Thorndike’s description of the law of effect was an important first step in understanding how active, voluntary behaviors can be modified by their consequences. Thorndike, however, never developed his ideas on learning into a formal model or system (Hearst, 1999). Instead, he applied his findings to education, publishing many books on educational psychology (Mayer & others, 2003). Some 30 years after Thorndike’s famous puzzle-box studies, the task of further investigating how voluntary behaviors are acquired and maintained would be taken up by another American psychologist, B. F. Skinner (Rutherford, 2012).

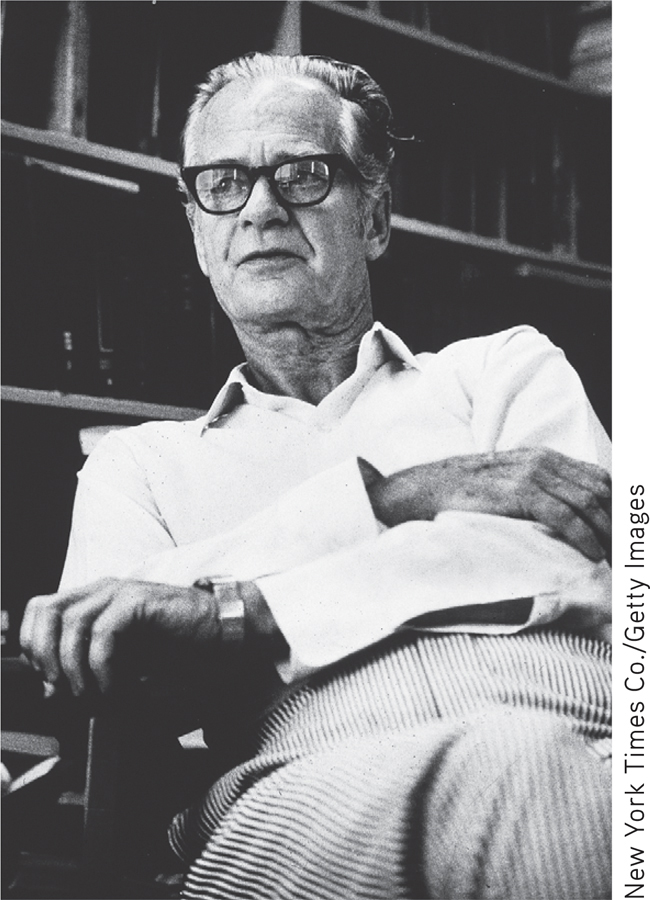

B. F. Skinner and the Search for “Order in Behavior”

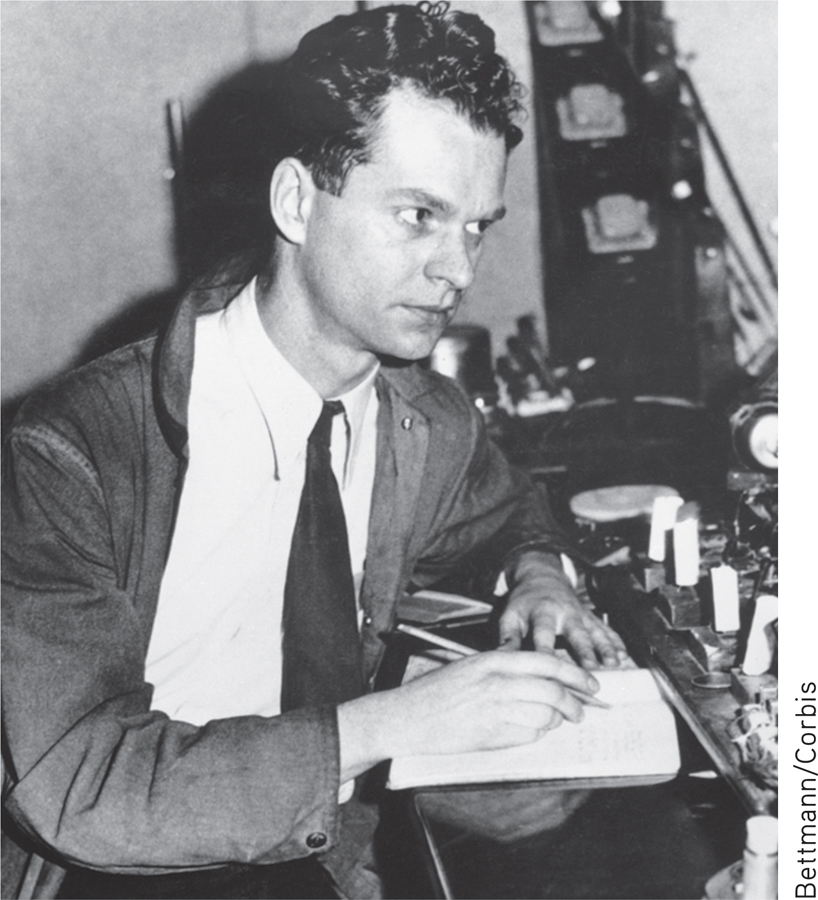

From the time he was a graduate student in psychology until his death, the famous American psychologist B. F. Skinner searched for the “lawful processes” that would explain “order in behavior” (Skinner, 1956, 1967). Like John Watson, Skinner was a staunch behaviorist. Skinner strongly believed that psychology should restrict itself to studying only phenomena that could be objectively measured and verified—outwardly observable behavior and environmental events.

Skinner acknowledged that Pavlov’s classical conditioning could explain the learned association of stimuli in certain reflexive responses (Iversen, 1992). But classical conditioning was limited to existing behaviors that were reflexively elicited. To Skinner, the most important form of learning was demonstrated by new behaviors that were actively emitted by the organism, such as the active behaviors produced by Thorndike’s cats in trying to escape the puzzle boxes.

Skinner (1953) coined the term operant to describe any “active behavior that operates upon the environment to generate consequences.” In everyday language, Skinner’s principles of operant conditioning explain how we acquire the wide range of voluntary behaviors that we perform in daily life. But as a behaviorist who rejected mentalistic explanations, Skinner avoided the term voluntary because it would imply that behavior was due to a conscious choice or intention.

operant

Skinner’s term for an actively emitted (or voluntary) behavior that operates on the environment to produce consequences.

Skinner defined operant conditioning concepts in very objective terms and he avoided explanations based on subjective mental states (Moore, 2005b). We’ll closely follow Skinner’s original terminology and definitions.

Reinforcement: INCREASING FUTURE BEHAVIOR

In a nutshell, Skinner’s operant conditioning explains learning as a process in which behavior is shaped and maintained by its consequences. One possible consequence of a behavior is reinforcement. Reinforcement is said to occur when a stimulus or an event follows an operant and increases the likelihood of the operant being repeated. Notice that reinforcement is defined by the effect it produces—increasing or strengthening the occurrence of a behavior in the future.

operant conditioning

The basic learning process that involves changing the probability that a response will be repeated by manipulating the consequences of that response.

reinforcement

The occurrence of a stimulus or event following a response that increases the likelihood of that response being repeated.

Let’s look at reinforcement in action. Suppose you put your money into a soft-drink vending machine and push the button. Nothing happens. You push the button again. Nothing. You try the coin-return lever. A shower of coins is released. In the future, if another vending machine swallows your money without giving you what you want, what are you likely to do? Hit the coin-return lever, right?

In this example, pushing the coin return lever is the operant—the active response you emitted. The shower of coins is the reinforcing stimulus, or reinforcer—the stimulus or event that is sought in a particular situation. In everyday language, a reinforcing stimulus is typically something desirable, satisfying, or pleasant. Skinner, of course, avoided such terms because they reflected subjective emotional states.

POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE REINFORCEMENT

There are two forms of reinforcement: positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement. Both affect future behavior, but they do so in different ways (see TABLE 5.1). It’s easier to understand these differences if you note at the outset that Skinner did not use the terms positive and negative in their everyday sense of meaning “good” and “bad” or “desirable” and “undesirable.” Instead, think of the words positive and negative in terms of their mathematical meanings. Positive is the equivalent of a plus sign (+), meaning that something is added. Negative is the equivalent of a minus sign (−), meaning that something is subtracted or removed. If you keep that distinction in mind, the principles of positive and negative reinforcement should be easier to understand.

Both positive and negative reinforcement increase the likelihood of a behavior being repeated. Positive reinforcement involves a behavior that leads to a reinforcing or rewarding event. In contrast, negative reinforcement involves behavior that leads to the avoidance of or escape from an aversive or punishing event. Ultimately, both positive and negative reinforcement involve outcomes that strengthen future behavior.

Comparing Positive and Negative Reinforcement

| Process | Operant Behavior | Consequence | Effect on Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive reinforcement | Studying to make dean’s list | Make dean’s list | Increase studying in the future |

| Negative reinforcement | Studying to avoid losing academic scholarship | Avoid loss of academic scholarship | Increase studying in the future |

Positive reinforcement involves following an operant with the addition of a reinforcing stimulus. In positive reinforcement situations, a response is strengthened because something is added or presented. Everyday examples of positive reinforcement in action are easy to identify. Here are some examples:

Your backhand return of the tennis ball (the operant) is low and fast, and your tennis coach yells “Excellent!” (the reinforcing stimulus).

You watch a student production of Hamlet and write a short paper about it (the operant) for 10 bonus points (the reinforcing stimulus) in your literature class.

You reach your sales quota at work (the operant) and you get a bonus check (the reinforcing stimulus).

positive reinforcement

A situation in which a response is followed by the addition of a reinforcing stimulus, increasing the likelihood that the response will be repeated in similar situations.

In each example, if the addition of the reinforcing stimulus has the effect of making you more likely to repeat the operant in similar situations in the future, then positive reinforcement has occurred.

It’s important to point out that what constitutes a reinforcing stimulus can vary from person to person, species to species, and situation to situation. While gold stars and stickers may be reinforcing to a third-grader, they would probably have little reinforcing value to your average high school student.

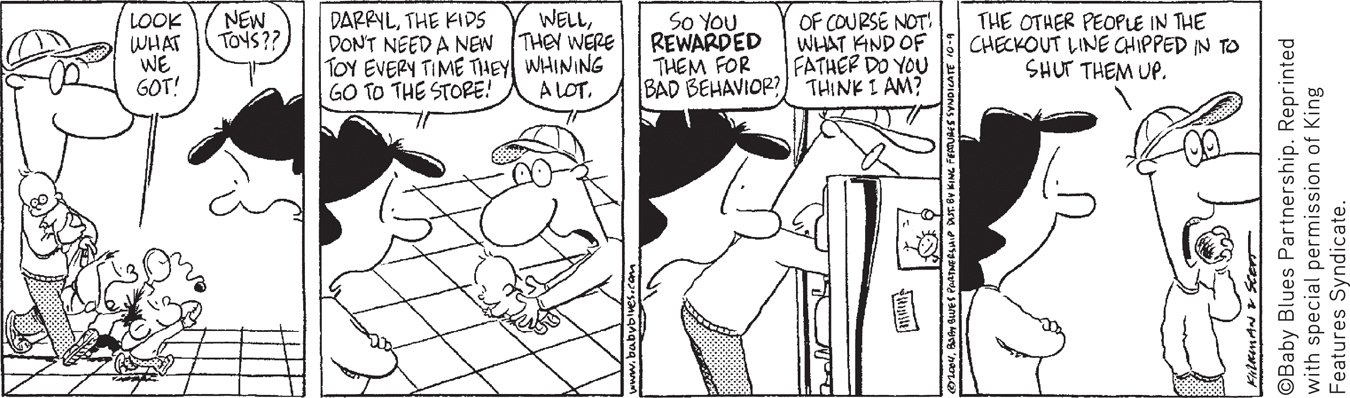

It’s also important to note that the reinforcing stimulus is not necessarily something we usually consider positive or desirable. For example, most teachers would not think of a scolding as being a reinforcing stimulus to children. But to children, adult attention can be a powerful reinforcing stimulus. If a child receives attention from the teacher only when he misbehaves, then the teacher may unwittingly be reinforcing misbehavior. The child may actually increase disruptive behavior in order to get the sought-after reinforcing stimulus—adult attention—even if it’s in the form of being scolded. To reduce the child’s disruptive behavior, the teacher would do better to reinforce the child’s appropriate behavior by paying attention to him when he’s not being disruptive, such as when he is working quietly.

Negative reinforcement involves an operant that is followed by the removal of an aversive stimulus. In negative reinforcement situations, a response is strengthened because something is being subtracted or removed. Remember that the word negative in the phrase negative reinforcement is used like a mathematical minus sign (−).

negative reinforcement

A situation in which a response results in the removal of, avoidance of, or escape from a punishing stimulus, increasing the likelihood that the response will be repeated in similar situations.

For example, you take two aspirin (the operant) to remove a headache (the aversive stimulus). Thirty minutes later, the headache is gone. Are you now more likely to take aspirin to deal with bodily aches and pain in the future? If you are, then negative reinforcement has occurred.

Think Like a SCIENTIST

What technology would help you break a bad habit—one that gives you rewards when you do well, or one that shocks you when you fail? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about Positive and Negative Reinforcement.

Aversive stimuli typically involve physical or psychological discomfort that an organism seeks to escape or avoid. Consequently, behaviors are said to be negatively reinforced when they let you either (1) escape aversive stimuli that are already present or (2) avoid aversive stimuli before they occur. That is, we’re more likely to repeat the same escape or avoidance behaviors in similar situations in the future. The headache example illustrates the negative reinforcement of escape behavior. By taking two aspirin, you “escaped” the headache. Paying your electric bill on time to avoid a late charge illustrates the negative reinforcement of avoidance behavior. Here are some more examples of negative reinforcement involving escape or avoidance behavior:

You make backup copies of important computer files (the operant) to avoid losing the data if the computer’s hard drive should fail (the aversive stimulus).

You dab some hydrocortisone cream on an insect bite (the operant) to escape the itching (the aversive stimulus).

You install a new battery (the operant) in the smoke detector to escape the annoying beep (the aversive stimulus).

In each example, if escaping or avoiding the aversive event has the effect of making you more likely to repeat the operant in similar situations in the future, then negative reinforcement has taken place.

PRIMARY AND CONDITIONED REINFORCERS

RJ Sangosti/The Denver Post via Getty Images

Skinner also distinguished two kinds of reinforcing stimuli: primary and conditioned. A primary reinforcer is one that is naturally reinforcing for a given species. That is, even if an individual has not had prior experience with the particular stimulus, the stimulus or event still has reinforcing properties. For example, food, water, adequate warmth, and sexual contact are primary reinforcers for most animals, including humans.

primary reinforcer

A stimulus or event that is naturally or inherently reinforcing for a given species, such as food, water, or other biological necessities.

A conditioned reinforcer, also called a secondary reinforcer, is one that has acquired reinforcing value by being associated with a primary reinforcer. The classic example of a conditioned reinforcer is money. Money is reinforcing not because those flimsy bits of paper and little pieces of metal have value in and of themselves, but because we’ve learned that we can use them to acquire primary reinforcers and other conditioned reinforcers. Awards, frequent-flyer points, and college degrees are just a few other examples of conditioned reinforcers.

conditioned reinforcer

A stimulus or event that has acquired reinforcing value by being associated with a primary reinforcer; also called a secondary reinforcer.

Conditioned reinforcers need not be as tangible as money or college degrees. Conditioned reinforcers can be as subtle as a smile, a touch, or a nod of recognition. Looking back at the Prologue, for example, Fern was reinforced by the laughter of her friends and relatives each time she told “the killer attic” tale—so she kept telling the story!

Punishment: USING AVERSIVE CONSEQUENCES TO DECREASE BEHAVIOR

KEY THEME

Punishment is a process that decreases the future occurrence of a behavior.

KEY QUESTIONS

How does punishment differ from negative reinforcement?

What factors influence the effectiveness of punishment?

What effects are associated with the use of punishment to control behavior, and what are some alternative ways to change behavior?

What are discriminative stimuli?

Positive and negative reinforcement are processes that increase the frequency of a particular behavior. The opposite effect is produced by punishment. Punishment is a process in which a behavior is followed by an aversive consequence that decreases the likelihood of the behavior’s being repeated. Many people tend to confuse punishment and negative reinforcement, but these two processes produce entirely different effects on behavior (see TABLE 5.2). Negative reinforcement always increases the likelihood that an operant will be repeated in the future. Punishment always decreases the future performance of an operant.

punishment

The presentation of a stimulus or event following a behavior that acts to decrease the likelihood of the behavior being repeated.

Punishment and negative reinforcement are two different processes that produce opposite effects on a given behavior. Punishment decreases the future performance of the behavior, while negative reinforcement increases it.

Comparing Punishment and Negative Reinforcement

| Process | Operant | Consequence | Effect on Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Punishment | Wear a warm but unstylish flannel shirt | A friend makes the hurtful comment, “Nice shirt. Whose couch did you steal to get the fabric?” | Decrease wearing the shirt in the future |

| Negative reinforcement | Wear a warm but unstylish flannel shirt | Avoid feeling cold and uncomfortable all day | Increase wearing the shirt in the future |

Skinner (1953) identified two types of aversive events that can act as punishment. Positive punishment, also called punishment by application, involves a response being followed by the presentation of an aversive stimulus. The word positive in the phrase positive punishment signifies that something is added or presented in the situation. In this case, it’s an aversive stimulus. Here are some everyday examples of punishment by application:

An employee wears shorts to work (the operant) and is reprimanded by his supervisor for dressing inappropriately (the punishing stimulus).

Your dog jumps up on a visitor (the operant), and you smack him with a rolled-up newspaper (the punishing stimulus).

You are late to class (the operant), and your instructor responds with a sarcastic remark (the punishing stimulus).

positive punishment

A situation in which an operant is followed by the presentation or addition of an aversive stimulus; also called punishment by application.

In each of these examples, if the presentation of the punishing stimulus has the effect of decreasing the behavior it follows, then punishment has occurred. Although the punishing stimuli in these examples were administered by other people, punishing stimuli also occur as natural consequences for some behaviors. Inadvertently touching a live electrical wire, a hot stove, or a sharp object (the operant) can result in a painful injury (the punishing stimulus).

The second type of punishment is negative punishment, also called punishment by removal. The word negative indicates that some stimulus is subtracted or removed from the situation (see TABLE 5.3). In this case, it is the loss or withdrawal of a reinforcing stimulus following a behavior. That is, the behavior’s consequence is the loss of some privilege, possession, or other desirable object or activity. Here are some everyday examples of punishment by removal:

After she speeds through a red light (the operant), her drivers’ license is suspended (loss of reinforcing stimulus).

Because he was flirting with another woman (the operant), a guy gets dumped by his girlfriend (loss of reinforcing stimulus).

negative punishment

A situation in which an operant is followed by the removal or subtraction of a reinforcing stimulus; also called punishment by removal.

To identify the type of reinforcement or punishment that has occurred, determine whether the stimulus is aversive or reinforcing and whether it was presented or removed following the operant.

Types of Reinforcement and Punishment

| Reinforcing stimulus | Aversive stimulus | |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulus presented | Positive reinforcement | Positive punishment |

| Stimulus removed | Negative punishment | Negative reinforcement |

However, many studies have demonstrated that physical punishment is associated with increased aggressiveness, delinquency, and antisocial behavior in the child (Gershoff, 2002; Knox, 2010; MacKenzie & others, 2012). In one study of almost 2,500 children, those who had been spanked at age three were more likely to be more aggressive at age five (Taylor & others, 2010). Other negative effects include poor parent–

In each example, if the behavior decreases in response to the removal of the reinforcing stimulus, then punishment has occurred. It’s important to stress that, like reinforcement, punishment is defined by the effect it produces. In everyday usage, people often refer to a particular consequence as a punishment when, strictly speaking, it’s not. Why? Because the consequence has not reduced future occurrences of the behavior. Hence, many consequences commonly thought of as punishments—being sent to prison, fined, reprimanded, ridiculed, or fired from a job—fail to reduce a particular behavior.

MYTH !lhtriangle! SCIENCE

Is it true that punishment is an effective way to teach new behaviors?

Why is it that aversive consequences don’t always function as effective punishments? Skinner (1953) as well as other researchers have noted that several factors influence the effectiveness of punishment (Horner, 2002). For example, punishment is more effective if it immediately follows a response than if it is delayed. Punishment is also more effective if it consistently, rather than occasionally, follows a response (Lerman & Vorndran, 2002; Spradlin, 2002). Though speeding tickets and prison sentences are commonly referred to as punishments, these aversive consequences are inconsistently applied and often administered only after a long delay. Thus, they don’t always effectively decrease specific behaviors.

Even when punishment works, its use has several drawbacks (see B. Smith, 2012). First, punishment may decrease a specific response, but it doesn’t necessarily teach or promote a more appropriate response to take its place. Second, punishment that is intense may produce undesirable results, such as complete passivity, fear, anxiety, or hostility (Lerman & Vorndran, 2002). Finally, the effects of punishment are likely to be temporary (Estes & Skinner, 1941; Skinner, 1938). A child who is sent to her room for teasing her little brother may well repeat the behavior when her mother’s back is turned. As Skinner (1971) noted, “Punished behavior is likelyc to reappear after the punitive consequences are withdrawn.” For some suggestions on how to change behavior without using a punishing stimulus, see the In Focus box, “Changing the Behavior of Others: Alternatives to Punishment.”

IN FOCUS

Changing the Behavior of Others: Alternatives to Punishment

Although punishment may temporarily decrease the occurrence of a problem behavior, it doesn’t promote more desirable or appropriate behaviors in its place. Throughout his life, Skinner remained strongly opposed to the use of punishment. Instead, he advocated the greater use of positive reinforcement to strengthen desirable behaviors (Dinsmoor, 1992; Skinner, 1971). Here are four strategies that can be used to reduce undesirable behaviors without resorting to punishment.

Strategy 1: Reinforce an Incompatible Behavior

The best method to reduce a problem behavior is to reinforce an alternative behavior that is both constructive and incompatible with the problem behavior. For example, if you’re trying to decrease a child’s whining, respond to her requests (the reinforcer) only when she talks in a normal tone of voice.

Strategy 2: Stop Reinforcing the Problem Behavior

Technically, this strategy is called extinction. The first step in effectively applying extinction is to observe the behavior carefully and identify the reinforcer that is maintaining the problem behavior. Then eliminate the reinforcer.

Suppose a friend keeps interrupting you while you are trying to study, asking you if you want to play a video game or just hang out. You want to extinguish his behavior of interrupting your studying. In the past, trying to be polite, you’ve responded to his behavior by acting interested (a reinforcer). You could eliminate the reinforcer by acting uninterested and continuing to study while he talks.

It’s important to note that when the extinction process is initiated, the problem behavior often temporarily increases. This situation is more likely to occur if the problem behavior has only occasionally been reinforced in the past. Thus, once you begin, be consistent in nonreinforcement of the problem behavior.

Strategy 3: Reinforce the Non-occurrence of the Problem Behavior

This strategy involves setting a specific time period after which the individual is reinforced if the unwanted behavior has not occurred. For example, if you’re trying to reduce bickering between children, set an appropriate time limit, and then provide positive reinforcement if they have not squabbled during that interval.

Strategy 4: Remove the Opportunity to Obtain Positive Reinforcement

It’s not always possible to identify and eliminate all the reinforcers that maintain a behavior. For example, a child’s obnoxious behavior might be reinforced by the social attention of siblings or classmates.

In a procedure called time-out from positive reinforcement, the child is removed from the reinforcing situation for a short time, so that the access to reinforcers is eliminated. When the undesirable behavior occurs, the child is immediately sent to a time-out area that is free of distractions and social contact. The time-out period begins as soon as the child’s behavior is under control. For children, a good rule of thumb is one minute of time-out per year of age.

Enhancing the Effectiveness of Positive Reinforcement

Often, these four strategies are used in combination. However, remember the most important behavioral principle: Positively reinforce the behaviors that you want to increase. There are several ways in which you can enhance the effectiveness of positive reinforcement:

Make sure that the reinforcer is strongly reinforcing to the individual whose behavior you’re trying to modify.

The positive reinforcer should be delivered immediately after the preferred behavior occurs.

The positive reinforcer should initially be given every time the preferred behavior occurs. When the desired behavior is well established, gradually reduce the frequency of reinforcement.

Use a variety of positive reinforcers, such as tangible items, praise, special privileges, recognition, and so on. Minimize the use of food as a positive reinforcer.

Capitalize on what is known as the Premack principle—a more preferred activity (e.g., painting) can be used to reinforce a less preferred activity (e.g., picking up toys).

Encourage the individual to engage in self-reinforcement in the form of pride, a sense of accomplishment, and feelings of self-control.

Question 5.7

i48PdRMVzcVdCGNKKxCvxeQo3gY1nxIByPLBuj3UX3r7c0f9ctRJeCj85IOytJm9WvQx9ottLHLtih658ll3vep6FFkI1KIL+zwrMucHSr+Ag0JBD8ngV675QKI3V1loX4G9WL7Iw3HyuZ3CY+MpztuldFaAMhi/SrWB5gyv8vwtBiJ1slTbiRcFmTUjJuqawGp/6M+RgUubUfB3WHGEtzxXwbXBjhH2zrSUKIjpUh+xBnhjpdWTG1XebAS81WstHC8slBMb4XADZkFIykCaAGGAo5FtzTQCLgJeQ7BOXK+Dvjz0S3VuXQpSVWfF5hhkhHPruI7Q+PVKCFDb0p+MKnottw1I8Va/vklL+qVdW9L1vnNEx7VzeC8lWsXhkXw92Tb5bzzcjh4=Discriminative Stimuli: SETTING THE OCCASION FOR RESPONDING

!launch!

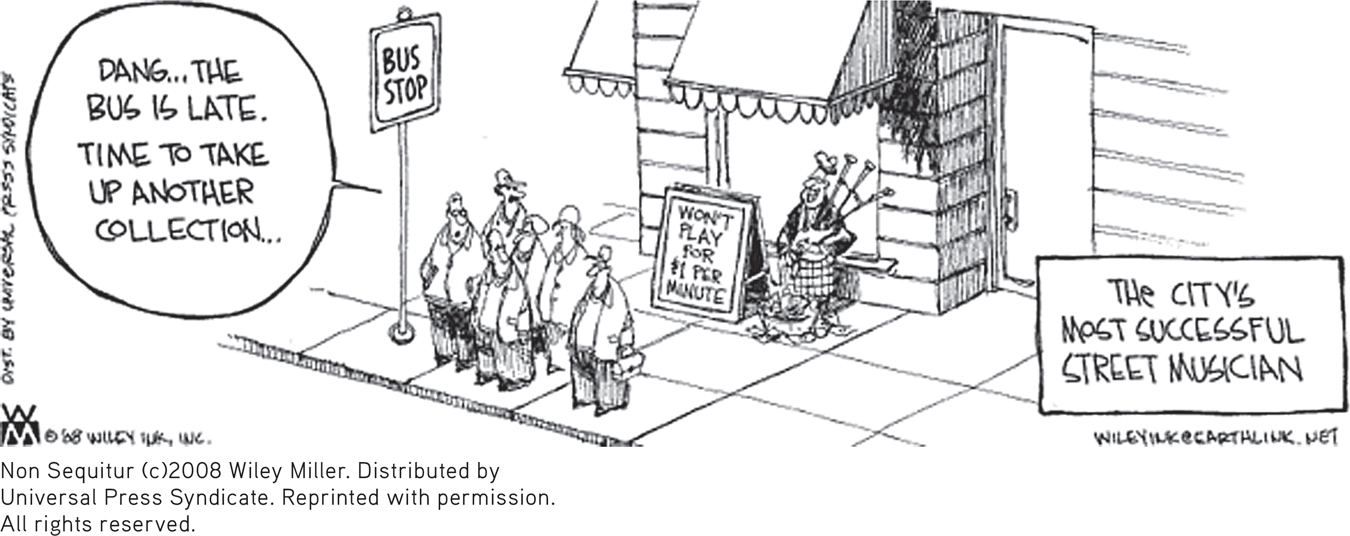

Another component of operant conditioning is the discriminative stimulus—the specific stimulus in the presence of which a particular operant is more likely to be reinforced. For example, a ringing phone is a discriminative stimulus that sets the occasion for a particular response—picking up the telephone and speaking.

discriminative stimulus

A specific stimulus in the presence of which a particular response is more likely to be reinforced, and in the absence of which a particular response is not likely to be reinforced.

This example illustrates how we’ve learned from experience to associate certain environmental cues or signals with particular operant responses. We’ve learned that we’re more likely to be reinforced for performing a particular operant response when we do so in the presence of the appropriate discriminative stimulus. Thus, you’ve learned that you’re more likely to be reinforced for screaming at the top of your lungs at a football game (one discriminative stimulus) than in the middle of class (a different discriminative stimulus).

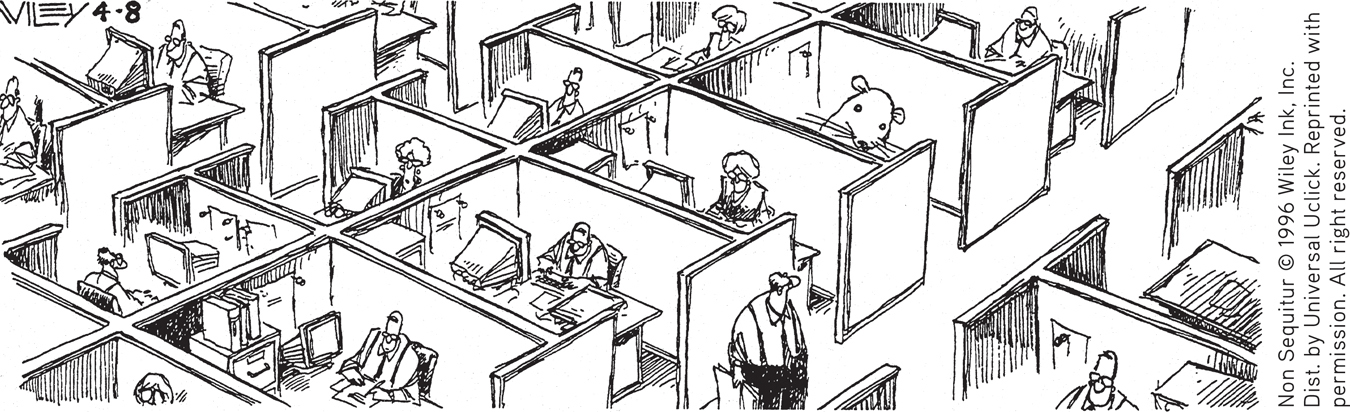

In this way, according to Skinner (1974), behavior is determined and controlled by the stimuli that are present in a given situation. In Skinner’s view, an individual’s behavior is not determined by a personal choice or a conscious decision. Instead, individual behavior is determined by environmental stimuli and the person’s reinforcement history in that environment. Skinner’s views on this point have some very controversial implications, which are discussed in the Critical Thinking box below, “Is Human Freedom Just an Illusion?”

CRITICAL THINKING

Is Human Freedom Just an Illusion?

Skinner was intensely interested in human behavior and social problems (Bjork, 1997). He believed that operant conditioning principles could, and should, be applied on a broad scale to help solve society’s problems. Skinner’s most radical—and controversial—belief was that such ideas as free will, self-determination, and individual choice are just illusions.

Skinner (1971) argued that behavior is not simply influenced by the environment but is determined by it. Control the environment, he said, and you will control human behavior. As he bluntly asserted in his controversial best-seller, Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971), “A person does not act upon the world, the world acts upon him.”

Such views did not sit well with the American public (Rutherford, 2003). Following the publication of Beyond Freedom and Dignity, one member of Congress denounced Skinner for “advancing ideas which threaten the future of our system of government by denigrating the American tradition of individualism, human dignity, and self-reliance” (quoted in Rutherford, 2000). Why the uproar?

Skinner’s ideas clashed with the traditional American ideals of personal responsibility, individual freedom, and self-determination. Skinner labeled such notions the “traditional prescientific view” of human behavior. According to Skinner, “A scientific analysis [of behavior] shifts both the responsibility and the achievement to the environment.” Applying his ideas to social problems, such as alcoholism and crime, Skinner (1971) wrote, “It is the environment which is ‘responsible’ for objectionable behavior, and it is the environment, not some attribute of the individual, which must be changed.”

To understand Skinner’s point of view, it helps to think of society as a massive, sophisticated Skinner box. From the moment of birth, the environment shapes and determines your behavior through reinforcing or punishing consequences. Taking this view, you are no more personally responsible for your behavior than is a rat in a Skinner box pressing a lever to obtain a food pellet. Just like the rat’s behavior, your behavior is simply a response to the unique patterns of environmental consequences to which you have been exposed. On the one hand, it may seem convenient to blame your history of environmental consequences for your failures and mistakes. On the other hand, that means you can’t take any credit for your accomplishments and good deeds, either!

Skinner (1971) proposed that “a technology of behavior” be developed, one based on a scientific analysis of behavior. He believed that society could be redesigned using operant conditioning principles to produce more socially desirable behaviors—and happier citizens (Goddard, 2014). He described such an ideal, utopian society in Walden Two, a novel he published in 1948.

Critics charged Skinner with advocating a totalitarian state. They asked who would determine which behaviors were shaped and maintained (Rutherford, 2000; Todd & Morris, 1992). As Skinner pointed out, however, human behavior is already controlled by various authorities: parents, teachers, politicians, religious leaders, employers, and so forth. Such authorities regularly use reinforcing and punishing consequences to shape and control the behavior of others. Skinner insisted that it is better to control behavior in a rational, humane fashion than to leave the control of behavior to the whims and often selfish aims of those in power.

Skinner’s ideas may seem radical or far-fetched. But some contemporary thinkers are already developing new ideas about how operant conditioning principles can be used to meet socially desirable goals. A movement called gamification advocates turning daily life into a kind of virtual reality game, in which “points” or other conditioned reinforcers are awarded to reward healthy or productive behaviors (Campbell, 2011). For example, some businesses give reductions on health insurance premiums to employees who rack up enough points on a specially equipped pedometer that monitors their daily activity level. The danger? Marketing professionals are already studying ways to use gamification to influence consumer preferences and buying decisions (Schell, 2010).

CRITICAL THINKING AND QUESTIONS

If Skinner’s vision of a socially engineered society using operant conditioning principles were implemented, would such changes be good or bad for society?

Are human freedom and personal responsibility illusions? Or is human behavior fundamentally different from a rat’s behavior in a Skinner box? If so, how?

Is your behavior almost entirely the product of environmental conditioning? Think about your answer carefully. After all, exactly why are you reading this box?

We have now discussed all three fundamental components of operant conditioning (see TABLE 5.4). In the presence of a specific environmental stimulus (the discriminative stimulus), we emit a particular behavior (the operant), which is followed by a consequence (reinforcement or punishment). If the consequence is either positive or negative reinforcement, we are more likely to repeat the operant when we encounter the same or similar discriminative stimuli in the future. If the consequence is some form of punishment, we are less likely to repeat the operant when we encounter the same or similar discriminative stimuli in the future.

The examples given here illustrate the three key components involved in operant conditioning. The basic operant conditioning process works like this: In the presence of a specific discriminative stimulus, an operant response is emitted, which is followed by a consequence. Depending on the consequence, we are either more or less likely to repeat the operant when we encounter the same or a similar discriminative stimulus in the future.

Components of Operant Conditioning

| Discriminative Stimulus | Operant Response | Consequence | Effect on Future Behavior | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | The environmental stimulus that precedes an operant response | The actively emitted or voluntary behavior | The environmental stimulus or event that follows the operant response | Reinforcement increases the likelihood of operant being repeated; punishment or lack of reinforcement decreases the likelihood of operant being repeated. |

| Examples | Wallet on college sidewalk | Give wallet to security | $50 reward from wallet’s owner | Positive reinforcement: More likely to turn in lost items to authorities |

| Gas gauge almost on “empty” | Fill car with gas | Avoid running out of gas | Negative reinforcement: More likely to fill car when gas gauge shows empty | |

| Informal social situation at work | Tell an off-color, sexist joke | Formally reprimanded for sexism and inappropriate workplace behavior | Positive punishment: Less likely to tell off-color, sexist jokes in workplace | |

| ATM | Insert bank card | Broken ATM machine eats your bank card and doesn’t dispense cash | Negative punishment: Less likely to use that ATM in the future |

Next, we’ll build on the basics of operant conditioning by considering how Skinner explained the acquisition of complex behaviors.

CONCEPT REVIEW 5.2

Reinforcement and Punishment

Identify the operant conditioning process that is being illustrated in each of the following examples. Choose from: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment.

Question 5.8

| 1. | When Joan turns the grocery cart down the candy aisle, her three-year-old son, Connor, starts screaming, “Want candy! Candy!” Joan moves to another aisle, but Connor continues to scream. As other customers begin staring and Joan starts to feel embarrassed, she finally gives Connor a bag of M&Ms. Connor is now more likely to scream in a store when he wants candy because he has experienced ____________ . |

Question 5.9

| 2. | If Joan is more likely to give in to Connor’s temper tantrums in public situations in the future, it is because she has experienced ____________ . |

Question 5.10

| 3. | Feeling sorry for a hitchhiker on the side of the road, Howard offered him a ride. The hitchhiker robbed Howard and stole his car. Howard no longer picks up hitchhikers because of ____________ . |

Question 5.11

| 4. | Jacob is caught playing solitaire on the computer in his office and gets reprimanded by his boss. Jacob no longer plays solitaire on his office computer because of ____________ . |

Question 5.12

| 5. | As you walk out of the shoe store at the Super Mall and turn toward another store, you spot a person whom you greatly dislike. You immediately duck back into the shoe store to avoid an unpleasant interaction with him. Because ____________ has occurred, you are more likely to take evasive action when you encounter people you dislike in the future. |

Question 5.13

| 6. | Having watched her favorite cartoon characters, the Powerpuff Girls, fly into the air on many episodes, four-year-old Tracey confidently climbs a stepladder, then launches herself into the air, only to tumble onto the grass. Because Tracey experienced ____________ , she tried this stunt only once. |

Question 5.14

| 7. | Thinking she was making a good impression in her new job by showing how knowledgeable she was, Tanya corrected her supervisor’s erroneous comments in two different meetings. Not long after the second meeting, Tanya was “let go” because of her bad attitude. Because she experienced ____________ , Tanya no longer publicly corrects her superiors. |

Shaping and Maintaining Behavior

KEY THEME

New behaviors are acquired through shaping and can be maintained through different patterns of reinforcement.

KEY QUESTIONS

How does shaping work?

What is the partial reinforcement effect, and how do the four schedules of reinforcement differ in their effects?

What is behavior modification?

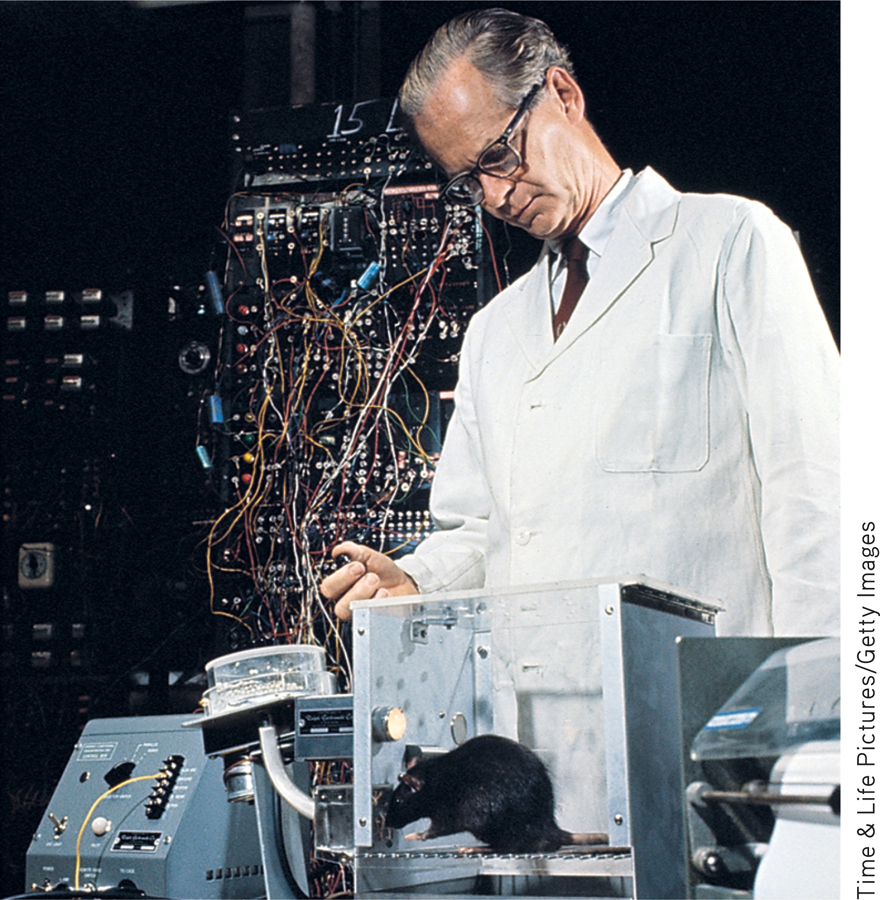

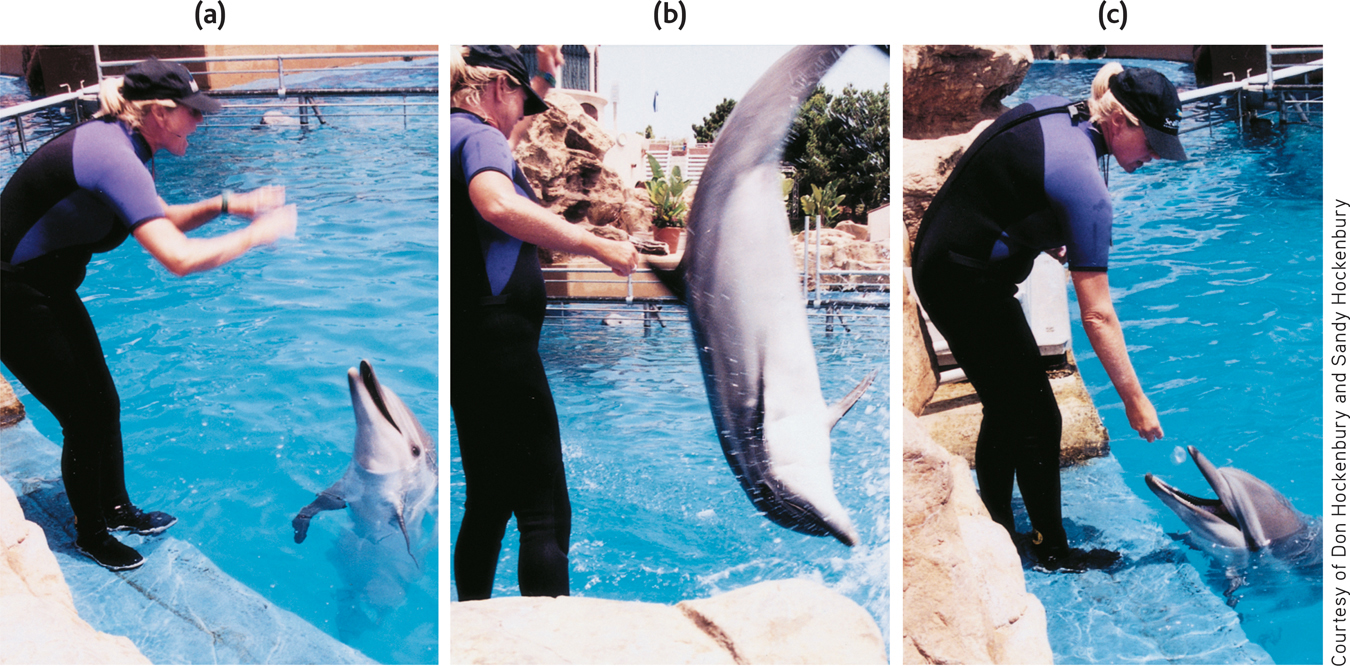

To scientifically study the relationship between behavior and its consequences in the laboratory, Skinner invented the operant chamber, more popularly known as the Skinner box. An operant chamber is a small cage with a food dispenser. Attached to the cage is a device that automatically records the number of operants made by an experimental animal, usually a rat or pigeon. For a rat, the typical operant is pressing a bar; for a pigeon, it is pecking at a small disk. Food pellets are usually used for positive reinforcement. Often, a light in the cage functions as a discriminative stimulus. When the light is on, pressing the bar or pecking the disk is reinforced with a food pellet. When the light is off, these responses do not result in reinforcement.

operant chamber or Skinner box

The experimental apparatus invented by B. F. Skinner to study the relationship between environmental events and active behaviors.

When a rat is first placed in a Skinner box, it typically explores its new environment, occasionally nudging or pressing the bar in the process. The researcher can accelerate the rat’s bar-pressing behavior through a process called shaping. Shaping involves reinforcing successively closer approximations of a behavior until the correct behavior is displayed. For example, the researcher might first reinforce the rat with a food pellet whenever it moves to the half of the Skinner box in which the bar is located. Other responses would be ignored. Once that response has been learned, reinforcement is withheld until the rat moves even closer to the bar. Then the rat might be reinforced only when it touches the bar. Step by step, the rat is reinforced for behaviors that correspond ever more closely to the final goal behavior—pressing the bar.

shaping

The operant conditioning procedure of selectively reinforcing successively closer approximations of a goal behavior until the goal behavior is displayed.

Skinner believed that shaping could explain how people acquire a wide variety of abilities and skills—everything from tying shoes to operating sophisticated computer programs. Athletic coaches, teachers, parents, and child-care workers all use shaping techniques.

THE PARTIAL REINFORCEMENT EFFECT: BUILDING RESISTANCE TO EXTINCTION

Once a rat had acquired a bar-pressing behavior, Skinner found that the most efficient way to strengthen the response was to immediately reinforce every occurrence of bar pressing. This pattern of reinforcement is called continuous reinforcement. In everyday life, of course, it’s common for responses to be reinforced only sometimes—a pattern called partial reinforcement. For example, practicing your basketball skills isn’t followed by putting the ball through the hoop on every shot. Sometimes you’re reinforced by making a basket, and sometimes you’re not.

continuous reinforcement

A schedule of reinforcement in which every occurrence of a particular response is followed by a reinforcer.

partial reinforcement

A situation in which the occurrence of a particular response is only sometimes followed by a reinforcer.

Now suppose that despite all your hard work, your basketball skills are dismal. If practicing free throws was never reinforced by making a basket, what would you do? You’d probably eventually quit playing basketball. This is an example of extinction. In operant conditioning, when a learned response no longer results in reinforcement, the likelihood of the behavior’s being repeated gradually declines.

extinction (in operant conditioning)

The gradual weakening and disappearance of conditioned behavior. In operant conditioning, extinction occurs when an emitted behavior is no longer followed by a reinforcer.

Skinner (1956) first noticed the effects of partial reinforcement when he began running low on food pellets one day. Rather than reinforcing every bar press, Skinner tried to stretch out his supply of pellets by rewarding responses only periodically. He found that the rats not only continued to respond, but actually increased their rate of bar pressing.

One important consequence of partially reinforcing behavior is that partially reinforced behaviors tend to be more resistant to extinction than are behaviors conditioned using continuous reinforcement. This phenomenon is called the partial reinforcement effect. For example, when Skinner shut off the food-dispensing mechanism, a pigeon conditioned using continuous reinforcement would continue pecking at the disk 100 times or so before the behavior decreased significantly, indicating extinction. In contrast, a pigeon conditioned with partial reinforcement continued to peck at the disk thousands of times! If you think about it, this is not surprising. When pigeons, rats, or humans have experienced partial reinforcement, they’ve learned that reinforcement may yet occur, despite delays and nonreinforced responses, if persistent responses are made.

partial reinforcement effect

The phenomenon in which behaviors that are conditioned using partial reinforcement are more resistant to extinction than behaviors that are conditioned using continuous reinforcement.

In everyday life, the partial reinforcement effect is reflected in behaviors that persist despite the lack of reinforcement. Gamblers may persist despite a string of losses, writers will persevere in the face of repeated rejection slips, and the family dog will continue begging for the scraps of food that it has only occasionally received at the dinner table in the past.

MYTH !lhtriangle! SCIENCE

Is it true that the most effective way to teach a new behavior is to reward it each time it is performed?

Skinner (1948b) pointed out that superstitions may result when a behavior is accidentally reinforced—that is, when reinforcement is just a coincidence. So although it was really just a fluke that wearing your “lucky” shirt or playing your “lucky” number was followed by a win, the illusion of reinforcement can shape and strengthen behavior.

Question 5.15

JP+0fJpflxK+WQmpMiFgUcQ7xB6ZhU8acE8pEyUL2vL+EHAYHsXKZWr+XXxa2ICL8pI6TAHiE64Tnb8vV5nEZvdxWTeuC2ejnQJsFNMMDNUHdm6Y6u5ZR/bk0O91JXAHOPJJcP48gw2ifBrVvCjGuoKAxJtxfx2WSMyVLPhaa6RcgDOpYw+2mpJjKGnHaS5ziZa+woqz51Uix2kbX1Tlw76ccUIIql55uEAHLP4UXRSkQmsRtZ9ZStrWxbxCY9rJU8d8NAPtt7kq+Ce6BHg7ENnNOqlz5VZiJ/wtBraqvK0lMDOxQBSQqcLmt+0pDT3UqUsIJYZ4iK8=THE SCHEDULES OF REINFORCEMENT

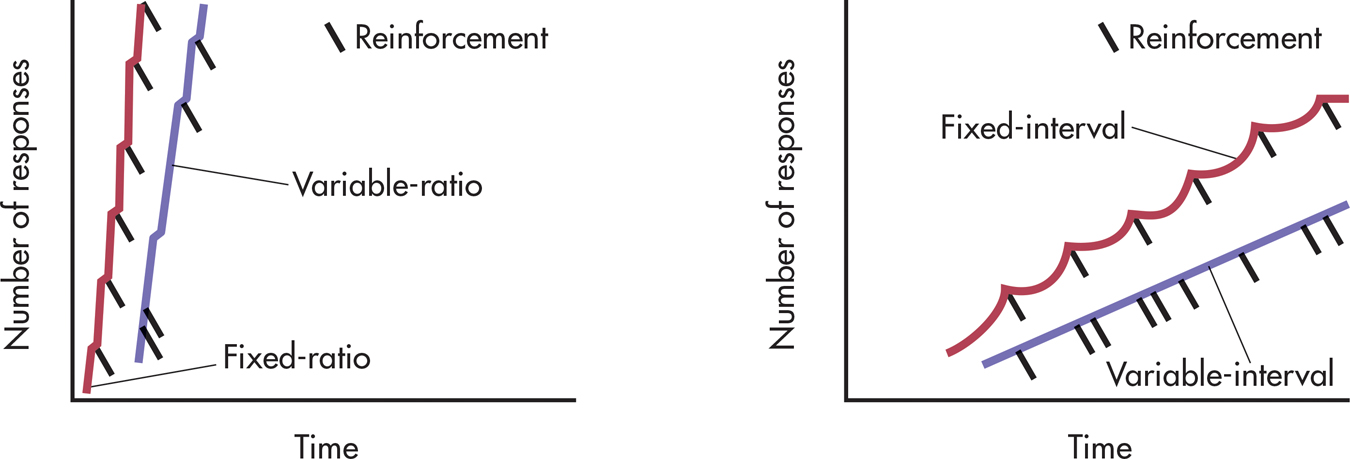

Skinner (1956) found that specific preset arrangements of partial reinforcement produced different patterns and rates of responding. Collectively, these different reinforcement arrangements are called schedules of reinforcement. As we describe the four basic schedules of reinforcement, it will be helpful to refer to FIGURE 5.5, which shows the typical pattern of responses produced by each schedule.

schedule of reinforcement

The delivery of a reinforcer according to a preset pattern based on the number of responses or the time interval between responses.

With a fixed-ratio (FR) schedule, reinforcement occurs after a fixed number of responses. A rat on a 10-to-1 fixed-ratio schedule (abbreviated FR-10) would have to press the bar 10 times in order to receive one food pellet. Fixed-ratio schedules typically produce a high rate of responding that follows a burst–

fixed-ratio (FR) schedule

A reinforcement schedule in which a reinforcer is delivered after a fixed number of responses has occurred.

With a variable-ratio (VR) schedule, reinforcement occurs after an average number of responses, which varies from trial to trial. A rat on a variable-ratio-20 schedule (abbreviated VR-20) might have to press the bar 25 times on the first trial before being reinforced and only 15 times on the second trial before reinforcement. Although the number of responses required on any specific trial is unpredictable, over repeated trials the ratio of responses to reinforcers works out to the predetermined average.

variable-ratio (VR) schedule

A reinforcement schedule in which a reinforcer is delivered after an average number of responses, which varies unpredictably from trial to trial.

Variable-ratio schedules of reinforcement produce high, steady rates of responding with hardly any pausing between trials or after reinforcement. Gambling is the classic example of a variable-ratio schedule in real life. Each spin of the roulette wheel, toss of the dice, or purchase of a lottery ticket could be the big one, and the more often you gamble, the more opportunities you have to win (and lose, as casino owners are well aware).

On a fixed-interval (FI) schedule, a reinforcer is delivered for the first response emitted after the preset time interval has elapsed. A rat on a two-minute fixed-interval schedule (abbreviated FI-2 minutes) would receive no food pellets for any bar presses made during the first two minutes. But the first bar press after the two-minute interval had elapsed would be reinforced.

fixed-interval (FI) schedule

A reinforcement schedule in which a reinforcer is delivered for the first response that occurs after a preset time interval has elapsed.

Fixed-interval schedules typically produce a scallop-shaped pattern of responding in which the number of responses tends to increase as the time for the next reinforcer draws near. For example, if your instructor gives you a test every four weeks, your studying behavior would probably follow the same scallop-shaped pattern of responding as the rat’s bar-pressing behavior. As the end of the four-week interval draws near, studying behavior increases. After the test, studying behavior drops off until the end of the next four-week interval approaches.

On a variable-interval (VI) schedule, reinforcement occurs for the first response emitted after an average amount of time has elapsed, but the interval varies from trial to trial. Hence, a rat on a VI-30 seconds schedule might be reinforced for the first bar press after only 10 seconds have elapsed on the first trial, for the first bar press after 50 seconds have elapsed on the second trial, and for the first bar press after 30 seconds have elapsed on the third trial. This works out to an average of one reinforcer every 30 seconds.

variable-interval (VI) schedule

A reinforcement schedule in which a reinforcer is delivered for the first response that occurs after an average time interval, which varies unpredictably from trial to trial.

Generally, the unpredictable nature of variable-interval schedules tends to produce moderate but steady rates of responding, especially when the average interval is relatively short. In daily life, we experience variable-interval schedules when we have to wait for events that follow an approximate, rather than a precise, schedule. For example, parents often unwittingly reinforce a whining child on a variable interval schedule. From the child’s perspective, the whining usually results in the desired request, but how long the child has to whine before getting reinforced can vary. Thus, the child learns that persistent whining will eventually pay off.

Applications of Operant Conditioning

The In Focus box on alternatives to punishment earlier in the chapter described how operant conditioning principles can be applied to reduce and eliminate problem behaviors. These examples illustrate behavior modification, the application of learning principles to help people develop more effective or adaptive behaviors. Most often, behavior modification involves applying the principles of operant conditioning to bring about changes in behavior.

behavior modification

The application of learning principles to help people develop more effective or adaptive behaviors.

Behavior modification techniques have been successfully applied in many different settings (see Kazdin, 2008). Coaches, parents, teachers, and employers all routinely use operant conditioning. For example, behavior modification has been used to reduce public smoking by teenagers (Jason & others, 2009), improve student behavior in school cafeterias (McCurdy & others, 2009), reduce problem behaviors in schoolchildren (Dunlap & others, 2010; Schanding & Sterling-Turner, 2010), and improve social skills and reduce self-destructive behaviors in people with autism and related disorders (Makrygianni & Reed, 2010).

Businesses also use behavior modification. For example, one large retailer increased productivity by allowing employees to choose their own reinforcers. A casual dress code and flexible work hours proved to be more effective reinforcers than money (Raj & others, 2006). In each of these examples, the systematic use of reinforcement, shaping, and extinction increased the occurrence of desirable behaviors and decreased the incidence of undesirable behaviors. In Chapter 15, on therapies, we’ll look at behavior modification techniques in more detail.

The principles of operant conditioning have also been used in the specialized training of animals, such as the Labrador shown at right, to help people who are physically challenged. Other examples are Seeing Eye dogs and capuchin monkeys who assist people who are severely disabled.

CONCEPT REVIEW 5.3

Schedules of Reinforcement

Indicate which of the following schedules of reinforcement is being used for each example: variable-interval (VI); fixed-interval (FI); variable-ratio (VR); fixed-ratio (FR).

Question 5.16

| 1. | ____________ A data-entry clerk is paid $1 for every 100 correct accounting entries made on the computer. |

Question 5.17

| 2. | ____________ At the beginning of the new term, your instructor announces that there will be five surprise quizzes over the course of the semester. |

Question 5.18

| 3. | ____________ At the beginning of the semester, your instructor announces that there will be a test every two weeks. |

Question 5.19

| 4. | ____________ On average, the campus shuttle bus passes the library about once every hour. |

Question 5.20

| 5. | ____________ Michael loves to play the slot machines, and, occasionally, he wins. |

Question 5.21

| 6. | ____________ Miguel works 40 hours a week in an office and gets paid every Friday afternoon. |