7.4 Measuring Intelligence

KEY THEME

Intelligence is defined as the global capacity to think rationally, act purposefully, and deal effectively with the environment.

KEY QUESTIONS

What roles did Binet, Terman, and Wechsler play in the development of intelligence tests?

How did Binet, Terman, and Wechsler differ in their beliefs about intelligence and its measurement?

Why are standardization, validity, and reliability important components of psychological tests?

Think Like a SCIENTIST

Can online brain games make you smarter? Go to LaunchPad: Resources to Think Like a Scientist about Brain Exercises.

Up to this point, we have talked about a broad range of cognitive abilities—the use of mental images and concepts, problem solving and decision making, and the use of language. All these mental abilities are aspects of what we commonly call intelligence.

What exactly is intelligence? We will rely on a formal definition developed by psychologist David Wechsler. Wechsler (1944, 1977) defined intelligence as the global capacity to think rationally, act purposefully, and deal effectively with the environment. Although many people commonly equate intelligence with “book smarts,” notice that Wechsler’s definition is much broader. To Wechsler, intelligence is reflected in effective, rational, and goal-directed behavior.

intelligence

The global capacity to think rationally, act purposefully, and deal effectively with the environment.

The Development of Intelligence Tests

Can intelligence be measured? If so, how? Intelligence tests attempt to measure general mental abilities, rather than accumulated knowledge or aptitude for a specific subject or area. In the next several sections, we will describe the evolution of intelligence tests, including the qualities that make any psychological test scientifically acceptable.

ALFRED BINET: IDENTIFYING STUDENTS WHO NEEDED SPECIAL HELP

To judge well, to comprehend well, to reason well, these are the essential activities of intelligence.

—Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon (1905)

In the early 1900s, the French government passed a law requiring all children to attend school. Faced with the need to educate children from a wide variety of backgrounds, the French government commissioned psychologist Alfred Binet to develop procedures to identify students who might require special help.

With the help of French psychiatrist Théodore Simon, Binet devised a series of tests to measure different mental abilities. Binet deliberately did not test abilities, such as reading or mathematics, that the students might have been taught. Instead, he focused on elementary mental abilities, such as memory, attention, and the ability to understand similarities and differences.

Binet arranged the questions on his test in order of difficulty, with the simplest tasks first. He found that brighter children performed like older children. That is, a bright 7-year-old might be able to answer the same number of questions as an average 9-year-old, while a less capable 7-year-old might do only as well as an average 5-year-old.

This observation led Binet to the idea of a mental level, or mental age, that was different from a child’s chronological age. An “advanced” 7-year-old might have a mental age of 9, while a “slow” 7-year-old might demonstrate a mental age of 5.

mental age

A measurement of intelligence in which an individual’s mental level is expressed in terms of the average abilities of a given age group.

It is somewhat ironic that Binet’s early tests became the basis for modern intelligence tests. First, Binet did not believe that he was measuring an inborn or permanent level of intelligence (Foschi & Cicciola, 2006; Kamin, 1995). Rather, he believed that his tests could help identify “slow” children who could benefit from special help (Newton & McGrew, 2010).

Second, Binet believed that intelligence was too complex a quality to describe with a single number (Siegler, 1992). He steadfastly refused to rank “normal” children on the basis of their scores, believing that such rankings would be unfair. He recognized that many individual factors, such as a child’s level of motivation, might affect the child’s score. Finally, Binet noted that an individual’s score could vary from time to time (Gould, 1993; Kaufman, 2009).

LEWIS TERMAN AND THE STANFORD–BINET INTELLIGENCE TEST

There was enormous interest in Binet’s test in the United States. The test was translated and adapted by Stanford University psychologist Lewis Terman. Terman’s revision was called the Stanford–

Terman adopted the suggestion of a German psychologist that scores on the Stanford–

intelligence quotient (IQ)

A measure of general intelligence derived by comparing an individual’s score with the scores of others in the same age group.

WORLD WAR I AND GROUP INTELLIGENCE TESTING

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, the U.S. military was faced with the need to rapidly screen 2 million army recruits. Using a group intelligence test designed by one of Terman’s students, army psychologists developed the Army Alpha and Beta tests. The Army Alpha test was administered in writing, and the Army Beta test was administered orally to recruits and draftees who could not read.

After World War I ended, the Army Alpha and Army Beta group intelligence tests were adapted for civilian use. The result was a tremendous surge in the intelligence-testing movement. Group intelligence tests were designed to test virtually all ages and types of people, including preschool children, prisoners, and newly arriving immigrants (Anastasi & Urbina, 1997; Kamin, 1995). However, the indiscriminate use of the tests also resulted in skepticism and hostility.

For example, immigrants were screened as they arrived at Ellis Island. The result was sweeping generalizations about the intelligence of different nationalities and races. During the 1920s, a few intelligence testing experts even urged the U.S. Congress to limit the immigration of certain nationalities to keep the country from being “overrun with a horde of the unfit” (see Kamin, 1995).

Despite concerns about the misuse of the so-called IQ tests, the tests quickly became very popular. Lost was Binet’s belief that intelligence tests were useful only to identify those who might benefit from special educational help. Contrary to Binet’s contention, it soon came to be believed that the IQ score was a fixed, inborn characteristic that was resistant to change (Gould, 1993).

Terman and other American psychologists believed that a high IQ predicted more than success in school. To investigate the relationship between IQ and success in life, Terman (1926) identified 1,500 California schoolchildren with “genius” IQ scores. He set up a longitudinal research study to follow their careers throughout their lives. Some of the findings of this landmark study are described in the In Focus box “Does a High IQ Score Predict Success in Life?” below.

DAVID WECHSLER AND THE WECHSLER INTELLIGENCE SCALES

The next major advance in intelligence testing came as a result of a young psychologist’s dissatisfaction with the Stanford–

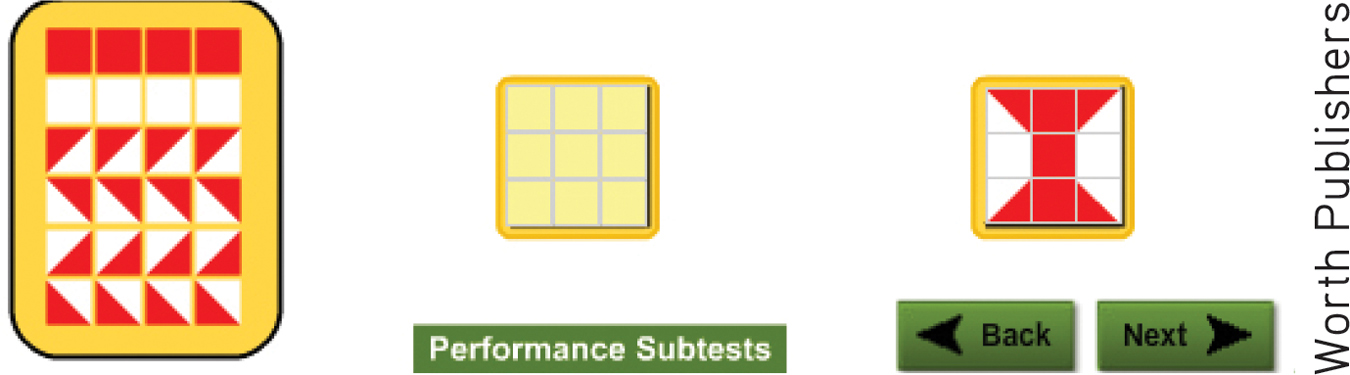

The WAIS had two advantages over the Stanford–

The design of the WAIS reflected Wechsler’s belief that intelligence involved a variety of mental abilities. Because the WAIS provided an individualized profile of the subject’s strengths and weaknesses on specific tasks, it marked a return to the attitudes and goals of Alfred Binet (Fancher, 1996; Sternberg, 1990).

The subtest scores on the WAIS also proved to have practical and clinical value. For example, a pattern of low scores on some subtests combined with high scores on other subtests might indicate a specific learning disability (Kaufman, 1990). Or someone who did well on the performance subtests but poorly on the verbal subtests might be unfamiliar with the culture rather than deficient in these skills (Aiken, 1997). That’s because many items included on the verbal subtests draw on cultural knowledge.

IN FOCUS

Does a High IQ Score Predict Success in Life?

In 1921, Lewis M. Terman identified 1,500 California girls and boys between the ages of 8 and 12 who had IQs above 140, the minimum IQ score for genius-level intelligence. Terman’s goal was to track these children by conducting periodic surveys and interviews to see how genius-level intelligence would affect the course of their lives.

Within a few years, Terman (1926) showed that the highly intelligent children tended to be socially well adjusted, as well as taller, stronger, and healthier than average children, with fewer illnesses and accidents. Not surprisingly, those children performed exceptionally well in school.

But how did Terman’s “gifted” children fare in the real world as adults? As a group, they showed an astonishing range of accomplishments (Terman & Oden, 1947, 1959). In 1955, when average income was $5,000 a year, the average income for the group was $33,000. Two-thirds had graduated from college, and a sizable proportion had earned advanced academic or professional degrees.

However, not all of Terman’s subjects were so successful. To find out why, Terman’s colleague Melita Oden compared the 100 most successful men (the “A” group) and the 100 least successful men (the “C” group) in Terman’s sample. Despite their high IQ scores, only a handful of the C group were professionals, and, unlike the A group, the Cs were earning only slightly above the national average income. In terms of their personal lives, the Cs were less healthy, had higher rates of alcoholism, and were three times more likely to be divorced than the As (Terman & Oden, 1959).

Given that the IQ scores of the A and C groups were essentially the same, what accounted for the difference in their levels of accomplishment? Terman noted that, as children, the As were much more likely to display “prudence and forethought, will power, perseverance, and the desire to excel.” As adults, the As were rated differently from the Cs on only three traits: They were more goal oriented, had greater perseverance, and had greater self-confidence. Overall, the As seemed to have greater ambition and a greater drive to achieve. In other words, personality factors seemed to account for the differences in level of accomplishment between the A group and the C group (Terman & Oden, 1959).

“With the exception of moral character, there is nothing as significant for a child’s future as his grade of intelligence.”

—Lewis M. Terman (1916)

As the general success of Terman’s gifted children demonstrates, high intelligence can certainly contribute to success in life. But intelligence alone is not enough. Although IQ scores do reliably predict academic success, success in school is no guarantee of success beyond school. Many different personality factors are involved in achieving success: motivation, emotional maturity, commitment to goals, creativity, and—perhaps most important—a willingness to work hard (Duckworth & others, 2007; Furnham, 2008). None of these attributes are measured by traditional IQ tests.

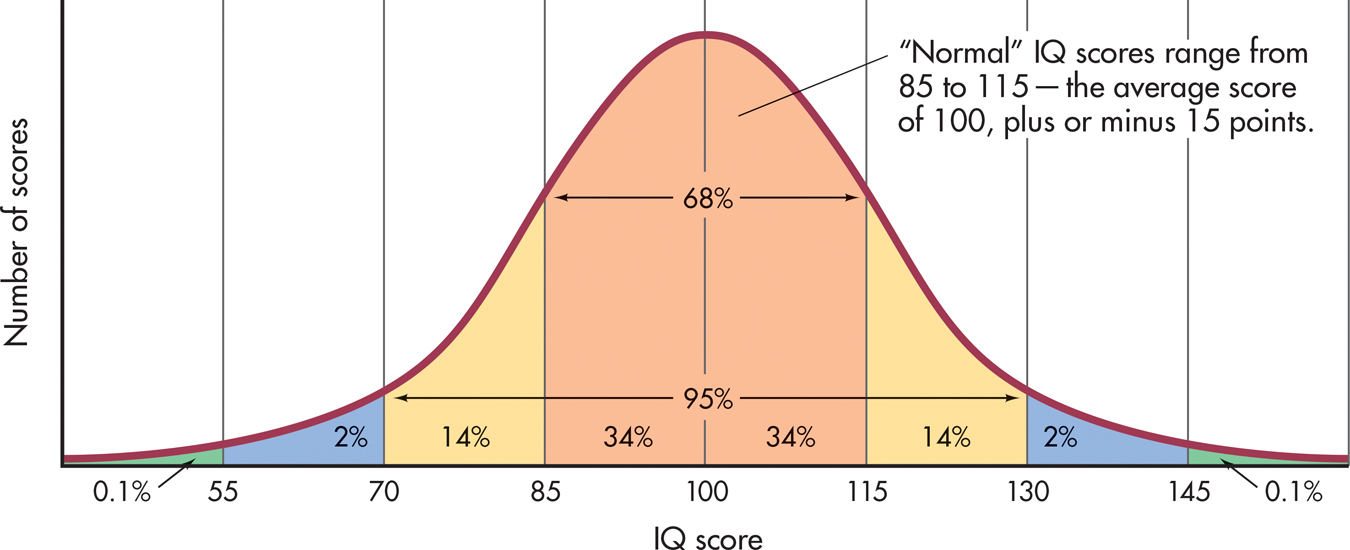

Wechsler’s test also provided an overall, global IQ score, but he changed the way that the IQ score was calculated. On the Stanford–

!launch!

Instead, Wechsler calculated the IQ by comparing an individual’s score with the scores of others in the same general age group, such as young adults. The average score for a particular age group was statistically fixed at 100. The range of scores is statistically defined so that two-thirds of all scores fall between 85 and 115—the range considered to indicate “normal” or “average” intelligence. This procedure proved so successful that it was adopted by the administrators of other tests, including the current version of the Stanford–

The WAIS was revised in 1981, 1997, and most recently, in 2008. The fourth edition of the WAIS is known as WAIS-IV. Since the 1960s, the WAIS has remained the most commonly administered intelligence test. Wechsler also developed two tests for children: the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) and the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI).

Question 7.13

18GEHl5nQzAsUJBPoMC7loFg9LKu4N6cDnAZAw3dRcdsHfjyPY3JpTUfHWQzys1s/pNl+filA4ywmEhWZGm9afRe4oVOo3I6BgSSzdBzB2pWXlx3w/04Do5bM1qkx/N1k4vWi9lpqtWkTLcK5SWxxCxj381kVBTLwGBYycWAOwSnncdnrIF9leud2oSF57ztU+wDpfDxVns/d483FEqOws25zAW8dX0dQcsnInOkPQHNsIxCWnO6s93OFYfzE8OmTKVbazPJrFSzWmRNPrinciples of Test Construction: WHAT MAKES A GOOD TEST?

Many kinds of psychological tests measure various aspects of intelligence or mental ability. Achievement tests are designed to measure a person’s level of knowledge, skill, or accomplishment in a particular area, such as mathematics or a foreign language. In contrast, aptitude tests are designed to assess a person’s capacity to benefit from education or training. The overall goal of an aptitude test is to predict your ability to learn certain types of information or perform certain skills.

achievement test

A test designed to measure a person’s level of knowledge, skill, or accomplishment in a particular area.

aptitude test

A test designed to assess a person’s capacity to benefit from education or training.

Any psychological test must fulfill certain requirements to be considered scientifically acceptable. The three basic requirements of good test design are standardization, reliability, and validity. Let’s briefly look at what each of those requirements entails.

STANDARDIZATION

If you answer 75 of 100 questions correctly, what does that score mean? Is it high, low, or average? For an individual’s test score to be interpreted, it has to be compared against some sort of standard of performance.

Standardization means that the test is given to a large number of subjects who are representative of the group of people for whom the test is designed. All the subjects take the same version of the test under uniform conditions. The scores of this group establish the norms, or the standards against which an individual score is compared and interpreted.

standardization

The administration of a test to a large, representative sample of people under uniform conditions for the purpose of establishing norms.

For IQ tests, such norms closely follow a pattern of individual differences called the normal curve, or normal distribution. In this bell-shaped pattern, most scores cluster around the average score. As scores become more extreme, fewer instances of the scores occur. In FIGURE 7.6, you can see the normal distribution of IQ scores on the WAIS-IV. About 68 percent of subjects taking the WAIS-IV will score between 85 and 115, the IQ range for “normal” intelligence. Less than one-tenth of 1 percent of the population have extreme scores that are above 145 or below 55.

normal curve or normal distribution

A bell-shaped distribution of individual differences in a normal population in which most scores cluster around the average score.

RELIABILITY

A good test must also have reliability. That is, it must consistently produce similar scores on different occasions. How do psychologists determine whether a psychological test is reliable? One method is to administer two similar, but not identical, versions of the test at different times. Another procedure is to compare the scores on one half of the test with the scores on the other half of the test. A test is considered reliable if the test and retest scores are highly similar when such strategies are used.

reliability

The ability of a test to produce consistent results when administered on repeated occasions under similar conditions.

VALIDITY

Finally, a good test must demonstrate validity, which means that the test measures what it is supposed to measure. One way to establish the validity of a test is by demonstrating its predictive value. For example, if a test is designed to measure mechanical aptitude, people who received high scores should ultimately prove more successful in mechanical jobs than people who received low scores.

validity

The ability of a test to measure what it is intended to measure.

Test your understanding of Measuring Intelligence with

.

.